Feature Story

‘My greatest fear is that we will return to the dark days of the epidemic’

21 May 2025

21 May 2025 21 May 2025UNAIDS Country Director reports on the impact of funding cuts to the HIV response

The HIV response in Zambia, known as a model of success in sub-Saharan Africa, is now facing major challenges following the abrupt and significant cuts to US funding. It has led to widespread disruption: clinics have closed, prevention services have been scaled back, and thousands have lost access to lifesaving medication. Yet the Zambian government and partners are stepping in to protect the progress made.

In this interview, UNAIDS Country Director for Zambia, Isaac Ahemesah, details the fallout from these funding decisions on health services, vulnerable communities, and the country’s ability to sustain progress against HIV-and outlines what is urgently needed to avert further health crisis.

“In 1997, life expectancy in Zambia was about 46 years due to HIV and AIDS. In 2023, it was nearly 66 years because of the investments made and the strong partnership.”

Q: How have the US funding cuts impacted the HIV response in Zambia?

Zambia has long relied on international aid, including substantial support from PEPFAR. Three years ago, the US government’s commitment stood at approximately US$ 402 million, which was subsequently reduced to US$ 392 million, and most recently to US$ 367 million. Despite these reductions, the contribution remains significant, not only to the HIV response, but to Zambia’s overall health sector. To put it in perspective, of the US$ 600 million in total US support to Zambia for development last year, US$ 367 million, around 60%, was allocated to HIV.

However, the abrupt funding cuts led to the termination of key programmes. More than 11 000 health workers supporting the HIV response, and approximately 23 000 health workers providing services for malaria, tuberculosis, and other health needs, were impacted.

Several essential initiatives were stopped. These include the closure of 32 wellness centres that served over 20 000 key populations, including LGBTQ+ people, sex workers, and people who inject drugs, across seven of Zambia’s ten provinces. These centres offered critical services such as HIV testing, treatment, and support.

All DREAMS programmes, which supported adolescent girls and young women in 22 districts, have also been shut down. This has cut off access to HIV prevention, life skills, and economic empowerment activities for thousands of vulnerable girls.

HIV prevention services have also been disrupted. Sixteen standalone centres providing voluntary medical male circumcision - a proven HIV prevention method - have ceased operations. Nearly half of Zambia’s pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) services, which help prevent HIV infection, were funded by the US and have now been discontinued.

Community-led monitoring programmes, which ensured quality and accountability in HIV care, have also been terminated. Furthermore, the Smart Health electronic medical records system, along with platforms used for forecasting and quantifying medical supplies, is no longer operational, making it increasingly difficult to manage patient care and maintain drug inventories.

Q: What will happen if the DREAMS programme is not reinstated?

Currently, Zambia records approximately 23 000 new HIV infections annually, with about 8700 occurring among young people aged 15 to 24. Notably, 60% of infections in this age group happen among girls.Without support for prevention and treatment interventions, new HIV infections could surge to 180 000 per year by 2030. Among young people, infections could rise to over 60 000 annually by 2030.

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) remains a growing concern in Zambia, and each GBV case carries a heightened risk of HIV transmission. Addressing this requires a coordinated, multi-sectoral approach that extends beyond HIV alone to include family planning and reproductive health services. National partners are working to reinvigorate this multi-sectoral response so that all relevant sectors-education, gender, internal affairs, and others-actively share responsibility for the HIV response.

Given the challenges, there is a pressing need to pursue local initiatives and mobilize alternative funding sources to support adolescent girls and young women, safeguarding their health and rights.

Q: Are there concerns about supplies of HIV medicines?

Yes, there is significant concern. At present, Zambia has sufficient antiretroviral (ARV) medication to last until the end of the year. However, the US has announced an additional US$50 million cut in funding for medicines and health commodities, effective from next year, due to concerns about drug theft. This will make it extremely difficult to ensure an uninterrupted supply of ARVs, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. There have already been reports of people living with HIV receiving reduced quantities of medication - less than the standard three- to six-month supply - due to ongoing uncertainty and challenges in stock management.

Q: What is UNAIDS doing to support Zambia during this crisis?

At the onset of the US funding freeze, UNAIDS immediately partnered with the Ministry of Health to convene national leadership and all key stakeholders. This was critical to coordinate a unified and effective response to the sudden disruption. We quickly led an impact assessment to understand how the freeze was affecting Zambia’s HIV response on the ground. This provided the data needed to guide urgent decisions.

One of our first steps was to work with the government and partners, we helped define a minimum package of essential HIV services that could realistically be maintained with the reduced resources available. We costed this package at about US$ 147 million and presented it to the Cabinet and Presidency for consideration in the national budget.

At the same time, we supported the development of the HIV Sustainability Roadmap, which explores alternative domestic financing options. This includes innovative approaches such as leveraging health insurance schemes and introducing total market strategies-for example, making PrEP and vaginal rings available through pharmacies.

We also worked closely with the Ministry of Health to revise policies to better fit the current context. For example, we supported allowing longer antiretroviral therapy refills—for up to six months–—to reduce the burden on both patients and the health system. We also helped adjust HIV testing protocols to manage limited supplies more effectively and piloted new service delivery models outside traditional health facilities to expand access.

At the operational level, we partnered with WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and others to monitor weekly stock levels of HIV commodities, ensuring timely responses to shortages. We support civil society organizations, especially those representing key populations, in transitioning clients from closed wellness centers to public health facilities, helping maintain continuity of care.

To address broader systemic challenges, UNAIDS contributed to the restructuring plan for the Zambia Medicines and Medical Supplies Agency to improve accountability and strengthen the supply chain.

Our Resource Allocation Forecasting Tool was used to estimate the real cost of sustaining Zambia’s HIV response, which we estimated at around US$ 150 million annually. This tool helps the government and partners plan budgets more effectively.

UNAIDS acts as the central hub for information-sharing and advocacy around the impact of US funding cuts. We regularly present needs assessments to the UN Country Team and support ongoing fundraising discussions to urgently mobilize resources to sustain services.

Finally, we have supported training for health workers to promote respectful, non-discriminatory care for key populations now accessing mainstream health services. This is vital to ensure no one is left behind despite the challenges.

Q: What is the solution to ensure sustainable financing for Zambia’s HIV response, and avoid such a crisis in the future?

The key to sustainable financing lies in increasing domestic funding and reducing reliance on external donors. While the recent US funding cuts were abrupt and challenging, this situation was not entirely unexpected. For years, Zambia and other countries have been encouraged to take greater ownership of their HIV responses. The real surprise was the speed and scale of the funding reductions.

To protect its HIV response, Zambia must now mobilize domestic resources. This includes engaging local philanthropic organizations, expanding the role of national health insurance schemes, and ensuring that HIV services are fully integrated within these systems. Innovative models like risk pooling and market-based access to prevention tools, such as making PrEP and vaginal rings available through pharmacies, will also be key to expanding reach and ensuring continuity.

On the global level, the HIV response must increasingly pivot toward long-acting treatment and prevention options, such as injectable PrEP and antiretroviral treatment. These innovations can help simplify adherence and improve outcomes.

Zambia is also exploring total market approaches, where the private sector helps supply prevention and treatment services. In addition, local production of ARVs could help reduce costs and improve supply chain stability.

Critically, the country has already shown that essential HIV services can be maintained on smaller budgets, provided resources are used efficiently. But for long-term sustainability, the government must take the lead. This means prioritizing HIV in the national budget and exploring innovative domestic revenue sources, such as earmarked taxes on alcohol, tobacco, or health products.

While international partners will remain important, the responsibility for a predictable, sustainable HIV response now rests squarely with Zambia itself—to protect the lives and health of its 1.4 million citizens living with HIV, and to ensure that no one is left behind.

Q: What’s your message to the international community?

Today, I believe the global HIV response stands at a crossroads. The decisions we make now will either help the world achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3.3—the target of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030—or risk a devastating reversal.

If we ease up, we could see a return to the 1990s, when new HIV infections spiraled out of control, HIV-related deaths surged, and the global economy suffered greatly.

All we ask for is a final push— a sustained commitment to support countries in fulfilling their promises to end AIDS as a public health threat. I urge the US government and all other donors to reconsider the recent funding cuts. We need to keep our foot firmly on the accelerator until we reach the finish line.

Otherwise, my greatest fear is that we will return to the dark days of the epidemic, with significant increases in new infections and deaths.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Following the US funding cuts in January, UNAIDS is working closely with governments and partners in affected countries to ensure that all people living with or affected by HIV continue to access life-saving services. For the latest updates, please visit unaids.org

Related resources

Watch: Integration of HIV services key

Watch: Final push needed

Region/country

Feature Story

HIV is increasing among men who have sex with men in Cambodia; One organization is trying to turn the tide

21 May 2025

21 May 2025 21 May 2025Chhum Vy, an outreach worker for Men’s Health Cambodia (MHC), lives in Steung Meanchey, a low-income neighborhood in southern Phnom Penh. She has converted her rental house into a makeshift community centre for gay and transgender people who live in the area. To get there you pass through a Buddhist temple compound, then head down narrow streets, just wide enough for a motorbike.

Ms Vy has taped health promotion posters to the walls and arranges HIV testing and prevention tools in a corner of her living room floor. Clients leave their shoes at the door and sit in a circle on the ground for her sensitization sessions.

“I work every day, seven days a week, sometimes in the evening depending on the needs of the client,” she said.

She is on the frontlines, tackling the toughest challenge facing Cambodia’s HIV response. While new infections in the southeast Asian nation are declining among all other groups, they are increasing among gay men and other men who have sex with men. The reasons for this are complicated.

Ron Sopheab said he has lost many gay friends to AIDS. In the early 2000s one of his friends committed suicide when his family kicked him out of the house, refused to even eat with him and allowed him just a small bed outside.

The MHC workers and clients agree that stigma and discrimination against both men who have sex with men and people living with HIV have declined since those days.

“A little remains, but it is at a lower level,” Mr Sopheab said.

However, he noted that gaps in Cambodia’s progressive HIV response can still leave people susceptible to stigma and discrimination. Despite practicing safer sex in his regular life, Mr Sopheab contracted HIV during three months in a detention center where there was no access to HIV prevention tools. MHC provides him with peer support to remain adherent to treatment and gives him transportation support to attend the clinic when needed.

For Pom Rotha, it is extreme poverty that makes her vulnerable. As she is currently living in a rental room and sometimes cannot afford to pay the room fee, she is unable to renew her national identification. That means she cannot access the social support services that are a lifeline for many Cambodians. She survives through sex work and says about 5% of her clients insist on not using condoms.

“I cannot say ‘no’ because I need the money,” she said. “I try to negotiate, but if it does not work… I let it be.”

MHC provides Ms Rotha with pre-exposure prophylaxis, a preventive medicine known as PrEP, to help her avoid HIV infection if she is exposed. She said this is how she has remained HIV-free despite the risks she’s felt forced to take.

But another danger is far more pervasive. Young gay men are using the internet to find sexual partners either on hookup sites or social media. Many of them do not have the information or support they need to protect themselves.

That is why MHC has developed a digital strategy. This approach complements the physical testing, counselling and peer services it offers in ten provinces. Bun Pheng manages the online content and is himself an influencer. His team develops social media materials and campaigns about HIV prevention and MHC services. Every week they host a Facebook Live featuring experts or celebrity guests. A separate team is responsible for reaching out to clients through the gay social networking apps Grindr and Blued. Part of Mr Pheng’s job is to monitor the online comments, answering questions and interacting with the audience.

“If someone needs services, I refer them to an outreach worker to make an appointment where it’s most convenient,” he said.

Clients are offered a range of options to meet them where they are.

They can come in for testing or be mailed a self-test kit (one option tests at the same time for syphilis). MHC provides counselling before forwarding the testing kits and takes those with reactive results to the lab for confirmation. This varied approach is meant to help reach the 8% of people living with HIV in Cambodia who are not yet aware of their HIV status.

Ms Vy shows off a range of HIV prevention options. She demonstrates correct condom and lubricant use. Then she explains the basics of PrEP.

The Khmer HIV/AIDS NGO Alliance (KHANA) sends a mobile van out every night to provide education and testing in hotspot areas where gay men and transgender people go to find partners.

UNAIDS Country Director to Cambodia, Lao PDR and Malaysia, Patricia Ongpin, said more investments are needed for these community-led approaches tailored for men who have sex with men.

“Communities are responding to the realities of people’s lives in a way that state services can’t,” Ms Ongpin said. “To end AIDS we must channel resources to the organizations with the best chance of reaching those who are now being left behind.”

At the end of Ms Vy’s Sunday evening session clients leave with a bow and a handful of condoms.

“Self-stigma is really high,” Ms Vy reflected. “Societal stigma has reduced a lot, but some people still don’t want to access the services. I even had one case where after counselling a person still decided to stay away from services until she died. That is what we are working to address.”

Region/country

Feature Story

Client-centered services speed up Cambodia’s progress to end AIDS

20 May 2025

20 May 2025 20 May 2025Arun Seang* works six days a week in a garment factory in Phnom Penh. In the past when he needed time off to go to the HIV clinic he came up with excuses. Now there’s no need. The National Clinic for AIDS, Dermatology and STDs (NCHADS) is open every day, including weekends.

The scheduling suggestion came from a community-led monitoring exercise and community feedback. It was initially implemented as part of an Australia-supported project managed by UNAIDS. When the experiment ended, the clinic maintained a seven-day week due to its popularity.

This is one of several approaches taken to make HIV prevention and treatment services in Cambodia more user-friendly. “The staff are really nice,” Mr Seang said following his Sunday afternoon treatment consultation. “They are welcoming and also, they maintain confidentiality. I feel very safe coming here.”

Integrated community support

Cultivating a sense of trust in the delivery of HIV care has been key to Cambodia’s progress toward ending AIDS. The country is one of the front-runners to reach the 95-95-95 global targets. Currently 92% of people living with HIV are aware of their status. Almost all diagnosed people are on HIV treatment and more than 98% of those on treatment have a suppressed viral load.

These results were unimaginable when Sovann Reatrey learned she was HIV-positive, 26 years ago. “In the early days it was completely different,” she said. “Before there was a lot of stigma and discrimination. Many healthcare providers gossiped about people in the clinic and kept their distance. Now there is a welcoming environment, good communication and close physical interaction.”

At NCHADS she helps achieve this. As an Antiretroviral Users Association (AUA) counsellor her work is fully integrated into the clinic’s operations rather than an add-on. Mrs Reatrey consults with patients when they are first diagnosed and throughout their treatment journey.

“It starts as a friendly discussion. I disclose my status and tell them ‘I am also living with HIV’. Some don’t believe me. They say, ‘you look very healthy, but you are like me?’ I reassure them that it’s true. This builds trust and a relationship so they can discuss their concerns openly,” she explained. “The interaction is not as client and healthcare provider, but rather as a friend and neighbour.”

Nhem Salat, another community worker, enrolls people for HIV treatment. “I smile and encourage them to raise any issues they have when they go to see the doctor,” said Mrs Salat. “It’s all about making them feel comfortable.”

One-stop services

The waiting room isn’t hemmed in by walls. Sunlight and breeze rush through. Rows of colorful flags hang from the ceiling. The space is decidedly—perhaps deliberately—open and bright.

Huge posters invoke celebrity and safety. Singer Nicky Nicky, influencers Yaro and Sinora Roath and drag queen performer Rebecca Chan promote HIV prevention and options including condoms, PrEP (medicine to prevent HIV) and self-testing.

In addition to its standard PrEP service, this month the clinic adds long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA), an injectable HIV prevention option that lasts for two months, and the Dapivirine Ring (DVR), a vaginal ring which slowly releases antiretroviral medicine to prevent HIV infection.

Multiple posters invite clients to get tested. Sexually transmitted infection screenings and treatments are available. Non-communicable disease services are provided. Mental health screenings are offered to everyone. Next on NCHADS’s to-do list: more work to make the service offering youth-friendly.

By design, the space is everything for everyone.

“This clinic is a one-stop shop so people can access whatever services they need. People living with HIV don’t want to move around to different places to get healthcare,” explained the clinic’s Deputy Manager, Dr Nhem Chantha.

In his examining room, Dr Chantha, explained to Mr Seang that his viral load will be checked annually. “The U=U (undetectable equals untransmittable) message has been integrated into counseling to all clients. We have a Telegram group, and we also share information on social media platforms. This makes the clients understand the benefit of having an undetectable viral load by taking their treatment so they cannot transmit HIV. Because of this, they are very happy and really adhere to the treatment.”

UNAIDS Country Director for Cambodia, Lao PDR and Malaysia, Patricia Ongpin, noted that the emphasis on community-led care and service integration ensures impact and sustainability. “Partners in government and community are working together to find solutions that get the most out of every interaction and investment,” she said. “When services are friendly and convenient, people will use them. Then we will further reduce new HIV infections and deaths.”

*(name changed to protect privacy)

Region/country

Feature Story

UNAIDS at the 78th World Health Assembly

19 May 2025

19 May 2025 19 May 2025At the 78th World Health Assembly UNAIDS is calling for urgent action to avoid millions of avoidable HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths.

As the world faces an unprecedented international funding crisis affecting global health security, UNAIDS is calling on governments and partners attending the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA) to urgently recommit to ending AIDS by 2030. UNAIDS is warning that without immediate action to dismantle barriers to healthcare, strengthen community-led responses, and unlock sustainable financing, decades of progress could be reversed and millions of lives put at risk.

The theme of the 78th World Health Assembly is One World For Health.

During the week, UNAIDS will be advocating for continued global solidarity and sustained political and financial commitment for the global HIV response as part of broader efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. This includes the need to scale up HIV services, including access to long acting injectables for HIV prevention which are almost 100% effective at preventing infections and could help countries move towards a sustainable HIV response.

UNAIDS will also be pushing for equitable, inclusive and rights-based approaches to pandemic preparedness and response, supported by lessons learned from the gains made against HIV. This means ensuring equal access to medical innovations and the centrality of community systems, data equity, access to innovations and the protection of human rights.

UNAIDS KEY EVENTS AT #WHA78

Wednesday 21 May - 08:30 – 10:00 CET

Ending inequalities in pandemic responses - The pandemic agreement and beyond

The Pandemic Agreement is a significant step forward in pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, based on the principles of equity and the full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of all persons. The panel will discuss how to ensure that those principles are adhered to as the Agreement is put into practice.

Panel members:

- Precious Matsoso, Co-Chair of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body for the Pandemic Agreement

- Nísia Trindade, former Minister of Health, Brazil

- Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director

Venue: Kofi Annan room - UNAIDS/WHO D Building

*WHA delegates can use their WHA accreditation badge to enter the UNAIDS building. Other attendees must register in advance here

To follow online click here

Wednesday 21 May - 18:30 – 21:00 CET

“A new era of HIV prevention; Accelerating access to long-acting prevention options through sustainable prevention systems and financing”

This High-Level Dialogue organized by the Global HIV Prevention Coalition and co-hosted by UNAIDS in collaboration with UNFPA, WHO and UNDP, the Federal Republic of Brazil and Kingdom of the Netherlands aims to galvanize political leadership, financing, and coordinated action to drive a transformational HIV prevention push. The meeting will serve as a platform for Ministers of Health, global health partners, pharmaceutical companies, and civil society to explore opportunities to expand access to new long-acting prevention technologies as a powerful addition to existing effective options.

Join UNAIDS leadership, representatives of UN partners and global health stakeholders as they discuss these issues with Ministers of Health, community representatives and leaders of pharmaceutical companies developing long-acting prevention options.

Venue: Kofi Annan room - UNAIDS/WHO D Building

Watch the livestream here

Thursday 22 May - 08:30 – 10:30 CET

The future of domestic health financing is now: Africa’s pathway for sustainable health systems

The panel discussion will explore how best to achieve financial sustainability of the health sector from different perspectives. Topics would include raising more money through innovative means, improving efficiency, strengthening planning and coordination, public-private partnerships as well as discussing the roles of different actors, including donor partners, and the institutional reforms necessary for success.

Co-organised by the Ministry of Health & Social Welfare of Nigeria, the Global Fund, WHO, UNAIDS and other partners

Venue: Ballroom AE, INTERCONTINENTAL GENEVE

Thursday 22 May - 18:30 – 20:30 CET

Communities at the heart of global health and health security: Why sustained funding for community-led health systems matters now more than ever.

Co-organised by UNAIDS, Coalition PLUS, Frontline AIDS and WHO, this event will bring together Ministers of Health, civil society leaders, donors, and global health institutions to explore sustainable solutions to safeguard and scale up community-led health systems amid global crises and decreasing aid.

Venue: Kofi Annan room - UNAIDS/WHO D Building

To attend in person, please register here

To attend online, please register here

Related resources

Feature Story

Côte d’Ivoire advances toward Universal Health Coverage—Leaving No One Behind

19 May 2025

19 May 2025 19 May 2025The government of Côte d’Ivoire is transforming access to health services, including HIV services, in its commitment to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

The government has made UHC registration mandatory and nearly 60% of the population is already enrolled, demonstrating the country’s political will to build a resilient and equitable health system.

A central priority of the Government’s UHC agenda—supported by the World Bank, the Global Fund and UNAIDS—is to ensure that all people living with HIV, estimated at over 400 000 people, are fully enrolled in the national health insurance scheme. Special attention is being given to identifying modalities through which the poorest and most vulnerable people living with HIV will benefit from free coverage under UHC.

In 2022, UNAIDS conducted an evaluation of Côte d’Ivoire’s social protection system through the lens of the HIV response. This work informed the 2024–2028 National Social Protection Strategy, which now explicitly recognizes people living with HIV as a priority vulnerable group.

“This is an urgent plea—I want all people living with HIV to have free access to the UHC card because many people simply cannot afford to contribute. I’m calling on the government to cover their premiums,” said Tinhidé Adéline, Community Counsellor.

Efforts are underway to integrate HIV-related services and products into the UHC benefits package. Over the past three years UNAIDS, in partnership with the Network of Organizations of People Living with HIV (RIP+), has mobilized communities and advocated with national authorities to ensure people living with HIV are enrolled in UHC, ensuring that stigma and exclusion do not stand in the way of health and dignity.

“UHC is a real opportunity for people living with HIV because being HIV-positive is often a barrier to accessing health insurance,” says Filbert Guéhi, Chair of the Board, RIP+.

UNAIDS, in collaboration with WHO, is also assisting RIP+ in developing a budgeted community-based strategy to sensitize and register people living with HIV in UHC to guarantee that services reach those most in need. This community-driven approach to UHC enrollment for people living with HIV represents a major step forward in ensuring equitable access to health care for vulnerable populations.

Advocacy continues to establish a sustainable national mechanism to automatically enroll the most vulnerable people living with HIV in the non-contributory Health Insurance Scheme. A two-year pilot initiative on this is currently being supported by The Global Fund and The World Bank. This is a vital step toward ensuring no one is left behind, and toward harnessing UHC as a powerful lever in the fight to end AIDS by 2030.

Ensuring full inclusion of people living with HIV in the roll out of UHC was a commitment made by the government at the annual session of the National AIDS Council in 2023 chaired by the Vice-President of Côte d’Ivoire Tiémoko Koné and in presence of the First Lady Madame Dominique Ouattara. This initiative is a cornerstone of the Government’s long-term strategy to transition towards a sustainable, nationally owned HIV response to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Championing the cause of women living with HIV in Cambodia

15 May 2025

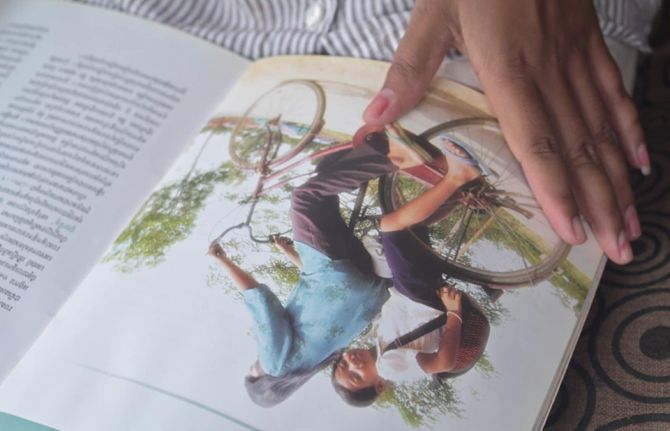

15 May 2025 15 May 2025Em Ra disappears into the house twice, slipping past the shrine of flowers and incense by the front door. First, she brings out an old HIV magazine. She flips to a page of a small child, sitting on the back seat of a bike, looking straight into the camera. Next, she emerges with two framed photographs from a recent university graduation.

The girl and the graduate are her daughter, Sorn Vichheka, twenty years apart. In 2005, the year the bicycle picture was taken, Vichheka started taking medicines. At first, she didn’t know why. When she was 12, she learned that she was born with HIV.

“I am not sure when I accepted myself fully,” she says from her verandah in Meanchey, a commune to the south of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh. “It was gradual.”

She looks out into a yard patrolled by chickens and surrounded by towering coconut trees. Under a shed in a nearby yard a baby sleeps in a hammock swung quickly back and forth by a string tied to its mother’s wrist. Vichheka’s sibling, who is HIV-negative, plays with the neighbours’ kids. They climb trees, dismounting onto the sides of concrete rainwater cisterns.

She traces her evolution from child to advocate. As a girl her mother was already involved in the HIV movement. Today Ra remains a community action worker with the Antiretroviral Users Association (AUA), helping other people at their treatment site. But as a teen, Vichheka was afraid of being found out.

“I started working for a company and did not disclose my status. At the same time, I was studying at the university. I was struggling with work and my studies, so I did not take my medicine regularly. Every time I went to the clinic co-workers would ask questions. They were curious to know what kind of health issue I had. I was very scared that people would know my HIV status,” she remembers.

Stressed, she ended up resigning from the job and dropping out of school. She soon began volunteering with an HIV organization. There, peers explained the concept of U=U (undetectable equals untransmittable) more clearly. She grasped that HIV treatment could not only keep her alive but make it impossible for her to pass the virus to others.

She also understood more clearly the issues women living with HIV were facing. Half of the people living with HIV in Cambodia are women. Five percent of women report recent intimate partner violence. Many are petrified about disclosing their status. Then there is the balancing act of self-care, family responsibility and economic survival.

“Some are housewives and need to take care of children so sometimes they don’t care much about their own health. Sometimes, because of the living conditions, they need to go to work to make an income to support the family. With this, they might miss some clinic appointments,” she explains.

Vichheka says that government social protection programmes offering free healthcare, nutrition support and cash transfers for women living with HIV have been vital. Community-led care is also required.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns when treatment access was interrupted, she joined the AUA. She participated in the community delivery of antiretrovirals for two years. After the project ended, she continued to volunteer. Between 2023 and 2024 Vichheka was driven, balancing volunteer work, daytime employment at an accounting company and evening study.

In 2023, the Cambodian Community of Women Living with HIV (CCW) — an organization that had been founded in 2008 but lost its financing in 2017— was revived thanks to small seed funding from UNAIDS for a U=U project.

That year, the Cambodian Network of People Living with HIV (CPN+) and International Community of Women Living with HIV Asia Pacific (ICWAP) mentored CCW to engage in a UNAIDS-funded Global Fund Grant Cycle 7 project. They successfully mobilized funding for 2025-2026. Vichheka was among three Cambodian participants in ICWAP’s Feminist School Leadership Training.

For the first time in over five years, CCW had a seat at the table. Vichheka was chosen by the members to be its coordinator.

“We set up a peer support group of women living with HIV who come together, share experiences and motivate one other. CCW also provides psychosocial support and connects women with job opportunities. The Global Fund investment will expand this work while conducting leadership training to build capacity among sub-national coordinators,” Vichheka explains.

Her leadership journey is a win against the odds. For her family it is also a full circle moment.

“I am really proud to have such a kind mother, taking care of me since an early age, knowing that I was born with HIV. She protected me all the time from outside society and kept me motivated,” she says.

Region/country

Feature Story

‘We Can’t Afford to Go Back’- UNAIDS Country Director on HIV funding cut in Eswatini

14 May 2025

14 May 2025 14 May 2025Eswatini, a country once described as the epicentre of the HIV epidemic with nearly 1 in 3 adults living with HIV in 2015 [adult HIV prevalence in 2015 was 31%]. But Eswatini managed to turn around its HIV epidemic, reducing new HIV infections from a peak of 21 000 per year in 2000 to 4 000 in 2023, a remarkable result, achieved with the support of US funding.

However, the sudden US funding cuts threaten to undo years of progress. We sat down with Nuha Ceesay, UNAIDS Country Director in Eswatini, to discuss the current situation, the impact on HIV services, and the way forward.

Q: How are US funding cuts impacting Eswatini’s HIV response?

Eswatini’s HIV response has been a success story, by transforming a crisis that once saw extremely high HIV prevalence rates, into a model of resilience and opportunity. But the recent US funding cuts, representing about half of the country’s HIV response budget, have left the people living with and affected by HIV in despair, the government was not notified and left unprepared, and the people working to end AIDS are in total shock. There is real concern that new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths will rise, reversing years of hard-won progress. The cuts threaten not just HIV treatment and prevention, but also the broader health system improvements, data collection, jobs and empowerment of people living with HIV.

Q: What disruptions are being seen on the ground?

The effects are immediate and widespread. HIV testing services, the gateway to treatment, are now limited. With fewer people being tested, many may unknowingly be infected with HIV, missing the chance for early treatment and increasing the risk of further transmission. This could push annual new infections, which are currently around 4 000, even higher, and add pressure to already strained treatment resources. Stockouts of antiretroviral, lab test kits, and condoms are expected within months, and health worker layoffs are affecting service delivery and quality data collection. Primary prevention services, such as medicine to prevent HIV (PrEP), education campaigns, and voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention (which is around 60% effective in preventing HIV) have also been scaled back or suspended.

We are also seeing a stop of the DREAMS programme which is a major setback for adolescent girls and young women, who are disproportionately affected by HIV in Eswatini. DREAMS provided prevention education, skills, and socio-economic support to young women. Its termination leaves them more vulnerable to infection and strips away resources that have been central to empowering this high-risk group. HIV prevalence among young women and girls aged between 15 and 24 years was 70% higher than among young men in Eswatini in 2023.

Read more about the impact on UNAIDS website

Q: How is UNAIDS responding to these challenges?

UNAIDS is working closely with the government and partners to continue the work of developing and implementing the HIV Sustainability Roadmap. This will help Eswatini’s HIV response to gradually shift from being reliant on international aid to increasing its domestic funding which will lead to the government taking full ownership of its HIV response. The first phase of this roadmap has already been launched, focusing on building resilience and long-term solutions.

UNAIDS has also worked closely with the Ministry of Health and partners to map the impact of the funding cuts, identify service gaps, and strategize on mitigating disruptions. Collaboration with the Ministry of Health, UN partners, and civil society remains central, but the transition to sustainability is a complex and gradual process.

Q: What’s your message to the international community?

The successes that we celebrate in the HIV response are built on mutual accountability and global solidarity. That’s what enabled countries like Eswatini to shift the narrative-from a crisis by leading a response that brought down new HIV infection to 4 000 compared to when new infections were as high as 21 000.

It is therefore devastating to see all the hard-won gains being reversed at this stage. This is the moment we need to come together in solidarity and in partnership to accelerate our collective efforts.

Ending the epidemic is like a marathon. We have run the race many miles, but the end is what matters. If we cannot reach that finish line, it means we have not completed, and we cannot afford that.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Following the US stop work order in January, UNAIDS is working closely with governments and partners in affected countries to ensure that all people living with or affected by HIV continue to access life-saving services.

For the latest updates, please visit unaids.org

Related resources

Watch: "Access to prevention services no longer available", Nuha Ceesay, Eswatini UNAIDS Country Director

Watch: UNAIDS actively working on forward planning with governments, says Eswatini country director

Watch: "From crisis to opportunity," says UNAIDS citing Eswatini HIV response

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

How US funding cuts could derail years of progress in Burundi’s HIV response

14 May 2025

14 May 2025 14 May 2025Q&A with UNAIDS Country Director in Burundi

International aid is shrinking, and countries are increasingly burdened by the need to prioritize debt repayment over essential services, including healthcare. This shift has left vulnerable populations more exposed, with the abrupt funding cuts by the United States throwing the HIV response in many countries into chaos. Burundi, unfortunately, is no exception. Across the country, HIV services have faced severe disruptions. Clinics are reducing their services, staff are being laid off, and thousands of people living with HIV are at risk of losing access to critical treatment.

In this interview, Marie Margarete Molnar, UNAIDS Country Director in Burundi, explains how communities are being affected, how the health system is coping, and what must happen next.

Q: Can you describe the current funding landscape for Burundi’s HIV response?

Burundi’s HIV response relies heavily on international aid - 95% of its funding comes from donors, with the US government contributing 51% through PEPFAR. This support sustained 10 major projects covering HIV prevention, treatment, and care for both the general population and vulnerable populations. PEPFAR also provided support to community-led monitoring projects and critical data system information.

Q: How have the recent US funding cuts affected these programmes?

Out of the 10 PEPFAR-funded projects, three were not eligible for the US waiver and had to stop operating. Some of the remaining seven, although eligible, could not resume their activities due to delays and financial uncertainty. As a result and based on an assessment conducted during the first month of the pause, at least 10 000 people living with HIV—who were among the 79 000 currently under treatment—have been directly affected. These individuals risk losing consistent access to medication and support services. In addition, 167 health professionals have lost their positions. These include doctors, nurses, psychologists, lab technicians, and community health workers—many of whom were directly providing HIV services. Financially, the immediate PEPFAR cut represents approximately US$ 6.5 million from the annual PEPFAR envelope of US$ 25 million for HIV in Burundi.

Q: What does this mean in practical terms for people on the ground?

Burundi had almost reached the 2025 ambitious targets: 95% of people living with HIV who know their HIV status, of whom 95% are on treatment and of the people on treatment 95% are virally suppressed. This was the result of strong collaboration between the government, civil society organizations and partners. The country was even recognized with an award. But now the third 95, on viral suppression, is declining because some people can no longer access viral load testing or follow-up services. If the situation continues, there is a high risk of an increase in new infections and a weakening of the entire HIV response system.

Q: What steps have the government and partners taken so far to respond to the crisis?

The government and partners acted quickly. UNAIDS conducted consultations during the first two weeks of February with key stakeholders. These consultations identified the scale of the impact and led to a series of recommendations that were shared with the Government and partners. The Ministry of Health together with UNAIDS and WHO held a two-day workshop with the PEPFAR implementing partners and civil society to understand how the cuts affected budgets, staffing, services, and beneficiaries and to brainstorm on rapid mitigation measures. As instances, it was recommended carrying out field missions to visit treatment sites and assess how services were coping without US support, forming a crisis response group and developing a national contingency plan. The government also began to identify treatment sites facing ARV shortages and organized a drug quantification workshop after PEPFAR-supported partners could no longer lead it.

Finalizing the HIV Sustainability Roadmap has also become a top priority. The roadmap is intended to guide how Burundi can finance and manage its HIV response without relying so heavily on external donors. We also discussed modeling different scenarios, from best case to worst case, based on whether funding returns or disappears entirely. These models would help us plan, reprioritize, and adapt strategies accordingly. We are also using the UNAIDS Rapid AIDS Financing Tool (RAFT) to get detailed data on how the funding cut is affecting commodities and staffing across the country.

Q: Is the government prepared to increase its contribution to its national HIV efforts?

It’s trying. Previously, funding for antiretroviral treatment was split between 76% from the Global Fund, 15% from the government, and 9% from PEPFAR. The government has now committed to covering partially that missing 9%. That shows political will. But it’s not just about medicine. It’s about health workers, community programmes and lab capacity. Burundi will need to restructure its approach by, for instance, integrating HIV into broader health and social protection systems, and significantly increase domestic health funding to reduce dependency, but this is difficult given the country's economic constraints.

Q: What’s your message to the international community?

Burundi is a fragile country facing multiple crises—economic instability, fuel shortages, emerging epidemics, and an influx of refugees from neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Despite these challenges, the country has made significant progress towards ending HIV, thanks to sustained investment in health including the HIV response. The risk now is losing these gains. Continued support from international partners is essential, not just for health but for the country’s overall development. At the same time, the Burundian government must increase its commitment to health funding. Only through global solidarity and strong political will can Burundi hope to end HIV by 2030.

The global community must understand that this is more than a budget line. It’s about lives, stability and global health security.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Following the US stop work order in January, UNAIDS is working closely with governments and partners in affected countries to ensure that all people living with or affected by HIV continue to access life-saving services. For the latest updates, please visit unaids.org

Related resources

Watch: Sustainability now a crucial issue in the HIV response

Watch: Multiple crises affecting Burundi

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Community-led HIV services under threat: global networks and UNAIDS track the impacts of the US funding cuts

13 May 2025

13 May 2025 13 May 2025Community-led organizations are the backbone of the HIV response in many countries, providing access to HIV services for key populations, advocating for human rights and monitoring the HIV response. However, data collected by community-led organizations shows mass shut-downs of life-saving, peer-led services, significant – or total – budget cuts, staff lay-offs and rising levels of stigma, discrimination and mortality rates.

Two new key population-led reports, one by Global Black Gay Men Connect (GBGMC) and another by the International Network of People Who Use Drugs (INPUD), document the consequences of the US President’s Executive Order in January 2025 which froze all US foreign assistance. These reports highlight how services led by and for key populations are facing deep uncertainty about their future due to the funding cuts and loss of staff.

In its Frozen Out report, GBGMC found that 36% of partners supported by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) shut down within one week of the Executive Order. Another 19% said they could not operate beyond one month without renewed support. Similarly, INPUD’s report The Human Cost of Policy Shifts describes significant disruptions across harm reduction programmes. Nearly half (45%) of the organizations surveyed reported major budget losses, and one in four lost between 75% and 100% of their harm reduction programming. Critical services including peer-led outreach, HIV and hepatitis C testing, opioid agonist therapy, and overdose prevention have been disrupted.

A cascading crisis

The GBGMC report states that nearly 93% of key population-serving partners in Kenya reported experiencing full or partial service shutdowns. In Nigeria, every PEPFAR implementing partner providing services to key populations was reportedly affected. Across Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria, an estimated 2.2 million people have lost access to key population-focused HIV prevention services.

The report also warns that even short-term interruptions can have life-threatening consequences. Each day, an estimated 200,000 people rely on receiving their HIV treatment through US government-funded sites. Interruptions risk treatment failure, HIV transmission and the emergence of resistance to HIV medicines. Prevention efforts are also at risk, with US government funding supporting nearly 90% of global pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) initiatives.

“The PEPFAR funding freeze has led to the closure of numerous organizations and the disruption of essential HIV prevention services, leaving millions at risk. Immediate action is imperative to restore funding and protect key populations from further harm,” says Micheal Ighodaro, Executive Director of GBGMC

Impacts on organizations led by people who use drugs

INPUD’s report, The Human Cost of Policy Shifts, provides a detailed picture of how harm reduction services have been devastated by the US funding cuts. Based on a global rapid assessment of 101 respondents, the report reveals that nearly half lost between 26% and 100% of their harm reduction budgets, and 23% lost more than three-quarters of their funding.

The most disrupted services included peer-led outreach (41%), legal and human rights support (36%), HIV testing (35%), services for women who use drugs (33%), and overdose prevention (25%). The consequences for individuals and communities have been severe. 47% of organizations reported that people are now going without harm reduction supplies such as sterile syringes and naloxone, and 46% said people are relying on underground or informal networks for access. 30% observed increases in overdose deaths. Additionally, 62% of organizations documented rising stigma and discrimination against people who use drugs.

The report also highlights a particularly stark impact on women who use drugs. Of the 54 organizations that previously offered tailored services for women, 68% halted outreach, and over a third had to reduce or close services altogether.

“While increasing overall funding is important, it is equally vital to ensure that organizations led by people who use drugs receive targeted support to run harm reduction services that effectively address their communities’ unique challenges and needs," says Anton Basenko, Executive Director of INPUD

Heightened stigma and structural risks

Even before the funding cuts, key populations faced legal and social barriers

including criminalization, discrimination, and denial of services. According to reports gathered through UNAIDS’ dialogues with global and regional networks, these challenges are now intensifying. Community organizations have documented a rise in harassment, hate speech and healthcare discrimination. In some countries, specialized clinics are being “mainstreamed” into general health systems without adequate training or protections ensuring safe access.

UNAIDS’ response and coordinated action

Since February 2025, UNAIDS has been convening biweekly virtual dialogues with global key population networks, civil society advocates and international partners to share updates, raise concerns, and coordinate efforts to protect HIV services. At the regional level, UNAIDS is also convening with networks and joining forces to document the impact of funding disruptions and shape collective responses. These engagements have informed UNAIDS’ advocacy and programming supporting the launch of tools like the Rapid Action Financing Tool, strengthening country-level tracking through the UNAIDS impact portal (launched in early 2025) and amplifying community voices at global forums such as the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women and the Human Rights Council. Through continued collaboration with country teams, regional networks, and civil society, UNAIDS remains committed to co-creating solutions and prioritizing community-led responses.

A call for urgent action

GBGMC and INPUD urge governments, donors, and development partners to take immediate steps to:

- Restore and increase funding for community-led and key population-focused services and establish dedicated funding streams for key population-led organizations

- Establish pooled emergency funding mechanisms to sustain prevention and harm reduction

- Ensure meaningful community engagement in funding, service design, and legal reform

- Protect peer-led HIV services, which are grounded in principles of dignity, safety, and equitable access

Related documents

Related

Feature Story

HIV services and social reintegration programmes for prisoners and newly released detainees in Kyrgyzstan at risk of collapse

08 May 2025

08 May 2025 08 May 2025On the outskirts of Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, a small house converted into a shelter welcomes people recently released from prison. The shelter is funded by the Global Fund/UNDP project “Effective Control of HIV Infection and Tuberculosis in the Kyrgyz Republic.”

Madina Toktogulova, head of the public foundation Istikhsan, which supports the shelter, is preparing to welcome her clients.

For 25 years, Madina has worked with people in prison, people who use drugs, and those living with HIV and tuberculosis. As a community representative, she was at the forefront of establishing the country’s first grassroots initiatives, self-help groups, and community-based organizations. She played a key role in developing social support and rehabilitation programmes for people in vulnerable situations.

Together with a group of like-minded colleagues, she established the country’s first peer support groups in correctional facilities. They persuaded prison administrations of the importance of providing HIV prevention services, including harm reduction, to people in prisons; they built relationships with prison health professionals, social workers, and psychologists; implemented HIV prevention projects; and helped people newly released from prison who had no place to stay, clothes, or money to return home.

Dr Gulsara Kukanova, a physician at the FSIN hospital-polyclinic in Kyrgyzstan, stressed how vital organizations like Istikhsan are the moment people are released from prison as some stop taking antiretroviral treatment or relapse into drug use. “We partner with organizations like Istikhsan and witness people rebuilding their lives — finding jobs, reuniting with family. Offering hope to someone who has lost it is invaluable.”

Madina knows that without food, shelter, or ID, HIV treatment is not a priority. That’s why she advocates for a comprehensive approach to reintegration.

“People need more than just medical care. They need psychological support, help finding a job, restoring their documents. Non-governmental organizations, with donor support, play this essential role — helping people rediscover themselves,” she explains.

Istikhsan’s work focuses on supporting incarcerated women. Madina says women are more emotionally vulnerable, more affected by violence – the harsh reality of prisons, trauma, stigma, and self-stigma. They are more likely to give up on therapy and lose hope.

“Society forgives men more easily. Women with a prison history are judged more harshly. Maybe because I’m a woman, I feel their pain more deeply,” she says.

The organization is currently providing support to all women living with HIV in a nearby prison. Thanks to their efforts, more than 20 women have been able to restore their identity documents, dozens are receiving psychological and medical support, starting HIV treatment, reconnecting with children, finding jobs, and reintegrating into society.

But all of this is now at risk. HIV prevention efforts built over years through partnerships with government, civil society, and international institutions face collapse due to shrinking funding from key donors, including PEPFAR and the Global Fund.

According to Madina, a systemic approach to reintegration is impossible without cooperation between government institutions and civil society.

“We have a very good probation law that provides a legal framework for supporting people on the path to resocialization. However, as with any system, there are times when resources and human capacity are not sufficient to reach everyone in need. That’s when civil society can step in — in partnership with the state and within the framework of the existing legislation,” she emphasizes.

While the Kyrgyz government fully covers HIV treatment, there’s a real risk that essential social and prevention services — post-release support, reintegration, temporary housing, documentation help, hygiene kits — will be lost without external aid.

“The loss of funding could dismantle the entire support system for women living with HIV in prison. These programmes are not charity; they’re investments in resilient health and social protection systems that can operate independently. Investing now means building a future where everyone’s right to health is protected,” says Meerim Sarybaeva, UNAIDS Country Director in Kyrgyzstan.

“For the first time, we’ve created a model where probation services, prisons, and NGOs collaborate daily, so no one falls through the cracks,” says Chinara Maatkerimova, Programme Officer at UNODC in Kyrgyzstan.

“If we disappear, who will hear them?” Madina asks. But she’s determined to continue — even if it means starting over — to advocate for sustainable funding and rebuild a system where every person, regardless of their past, has a right to health and a future.

As of April 1, 2025, Kyrgyzstan has reported 14,609 cases of HIV. Of these, 61.8% were transmitted sexually and 27.8% through injection drug use. HIV is increasingly being detected among people outside of traditional key populations — a sign of the epidemic’s broader spread in the country.

Region/country

Related

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025