Feature Story

Empowering young Brazilians to talk to their peers about HIV

11 October 2019

11 October 2019 11 October 2019New HIV infections in Brazil increased by more than 20% between 2010 and 2018, so it’s crucial that young Brazilians start talking about HIV and learn how to protect themselves. That’s the aim of a project led by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Swiping through one of his social media accounts, Jonas da Silva checks out the latest parties and public events in Salvador. He is also chatting online with other young people. They talk about sex, how and if they use condoms with their partners, what they know about HIV prevention and if they have been tested for HIV.

“What’s cool about the project is that we have young people talking to young people. We use our language and slang to address HIV,” he says. “This connection is vital. We can see they trust us, and this is when we know we have touched them with the information they need.”

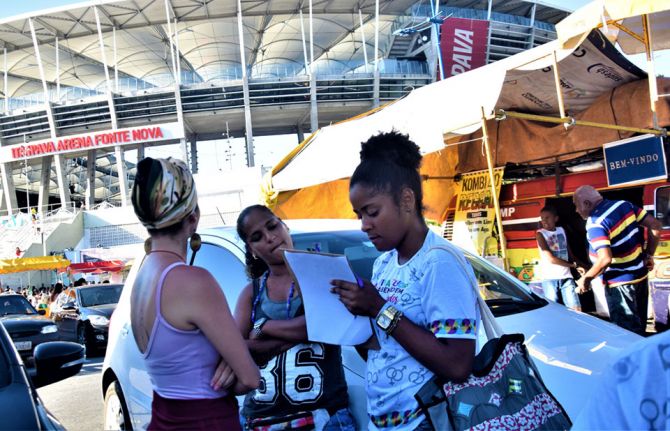

He and another 30 young people have been trained to work as volunteers in the Viva Melhor Sabendo Jovem (VMSJ) Salvador project. Their goal is to raise awareness among other young people about the importance of HIV testing and prevention. For that, they need to be where their peers are—online and on the street.

The project follows the calendar of traditional street parties and festivals, especially those that attract a large concentration of young people. It also responds to specific demands from key populations by mapping public gatherings where young lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people hang out. With a colourful small truck—the Test Truck—Mr da Silva and his co-volunteers can provide privacy for people who want HIV counselling and testing.

Since the project launched in August 2018, more than 1000 young people aged between 16 and 29 years have been tested for HIV in around 30 outings for the truck. As part of a strategy to promote testing among adolescents and young people, the volunteers also facilitate workshops on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and host talks about sexuality and sexual health in schools. These events reached more than 400 students in the first six months of the project.

“The VMSJ Salvador peer education methodology makes it possible to engage more young people in these activities. It also helps them to become aware of the importance of HIV prevention and care,” said Cristina Albuquerque, Chief of Health and HIV/AIDS for UNICEF in Brazil. “Young people who get tested during our activities congratulate the initiative and complain that they have very few of these opportunities around town.”

In 2018, according to Ministry of Health estimates, young people aged between 15 and 24 years represented almost 15% of all new HIV diagnoses in Salvador.

“For us, too, the volunteers, this experience is important because we also start to take better care of ourselves, to apply these prevention methods to our lives and to pass the message on to those around us, to our friends and family,” said Mr da Silva.

The project is implemented in partnership with GAPA Bahia―one of the oldest nongovernmental organizations dealing with HIV issues in the country―and counts on the support of the UNAIDS office in Brazil. The young volunteers all went through a rigorous selection process before undergoing a training programme that included topics such as human rights, counselling and information on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. They were also trained on community-based programmes, the functioning of the public health system and HIV services available in Salvador. The initiative includes a continuous training strategy on related topics.

“One of the most important things I have learned is that we have to respect each other’s choices and that we are here only to assist with information and inputs that we consider most appropriate to that person’s history and behaviour”, said Islan Barbosa, another of the volunteers.

“The project represents an important response to HIV testing demands in the city, especially among key populations, who very often avoid using public health facilities for that purpose. We are taking HIV testing to where these people are,” said Ms Albuquerque.

Related

Lower prices needed for new HIV prevention medicine in Brazil

Lower prices needed for new HIV prevention medicine in Brazil

09 September 2025

“Who will protect our young people?”

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025

Feature Story

Two decades of engagement in the response to HIV in Brazil

14 October 2019

14 October 2019 14 October 2019Seven years after finding out that he was living with HIV, Jair Brandão was waiting for a medical appointment in a clinic in Recife, north-east Brazil, when a fellow patient informed him he could access psychosocial support at a nearby nongovernmental organization. Although it had taken him many years to accept his HIV status, he needed just three sessions of counselling to realize that he was meant to become an HIV activist.

“I was thrilled and scared at the same time, because I didn’t understand much about political spaces, nor about AIDS and health policies. I didn't know how to engage in political discussion,” recalls Mr Brandão, who two decades later is one of Brazil’s most influential HIV activists. “First, I had to accept myself as a person living with HIV, and this was one of the challenges. And then learn about the virus, take care of myself. Only after that did I start to learn about social and political issues.”

Mr Brandão says he believes that being an activist is natural for him. “Some people are born for that,” he says. “Being an activist is about being restless and not accepting injustices and violations of rights. I think I was born with this gift because I always led processes, even without knowing it was activism, and I was always concerned about helping and empowering others.”

After participating in three of the four United Nations high-level meetings on AIDS and in the 2018 high-level meeting on tuberculosis, Mr Brandão knows how difficult it is to engage in dialogues with other civil society peers and country representatives. His mother tongue is Portuguese, which is not an official United Nations language. “Speaking a foreign language is a major issue for us in Brazil, so we have to know at least Spanish. Very few activists know English fluently enough to be able to make interventions in these spaces.”

In July 2019, Mr Brandão was among the nongovernmental organization delegates at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in New York, United States of America, representing RNP+ (the Network of People Living with HIV and AIDS) and his own nongovernmental organization, Gestos: Soropositividade, Comunicação e Gênero.

“It is essential for civil society to participate in the national implementation and monitoring processes of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development effectively. We cannot achieve the Sustainable Development Goals without the full participation of civil society,” he says. “Defending the AIDS agenda also requires discussing other equally important and cross-cutting issues.”

Through his role as Project Adviser at Gestos and as a member of RNP+, Mr Brandão also leads the People Living with HIV Stigma Index 2.0 project in Brazil. With his peers at Gestos and other national networks of people living with HIV, and with the support of the United Nations Development Programme and UNAIDS, he helped train 30 people on interviewing techniques in seven Brazilian cities. In two months, they gathered information about HIV-related stigma and discrimination by conducting around 1800 interviews. The initial results will be released before the end of November.

“This process strengthened the activists who conducted the interviews because they could listen to and experience the stories that many people have been through and could not until now share with anyone,” he recalls. “We are in the fourth decade of the AIDS epidemic and still there is a lot of stigma and discrimination. The Stigma Index 2.0 is an instrument which gives us evidence of that in Brazil. We will be able to advocate for stigma-free, zero discrimination HIV policies and services.”

Mr Brandão says he believes in the power of collaboration and partnership to achieve social progress.

“The solidarity and spirit of community that helped create the AIDS movement must come back in our actions and hearts,” he says. “Rethinking strategies and creating new ways to bring about change is fundamental. Empowering new activists, especially young people, is critical. Young people need to be welcomed and open to receive information from experienced AIDS activists. It’s time to join forces, not to be divided.”

Related

Feature Story

Investing in communities to make a difference in western and central Africa

09 October 2019

09 October 2019 09 October 2019Home to 5 million people living with HIV, western and central Africa is not on track to ending AIDS by 2030. Every day, more than 760 people become newly infected with HIV in the region and only 2.6 million of the 5 million people living with HIV are on treatment.

Insufficient political will, frail health systems and weak support for community organizations―as well as barriers such as HIV-related criminalization―are the most significant obstacles to progress. A regional acceleration plan aims to put the region on track to reaching the target of tripling the number of people on antiretroviral therapy by 2020 and achieving epidemic control. While progress has been made, that progress is not coming fast enough. Children are of particular concern―only 28% of under-15-year-olds living with HIV in the region have access to antiretroviral therapy.

“We need policies and programmes that focus on people not diseases, ensuring that communities are fully engaged from the outset in designing, shaping and delivering health strategies,” said Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i., speaking at the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Sixth Replenishment Conference, taking place in Lyon, France, on 9 and 10 October.

There are many examples of how investing in communities can make a difference. “The response is faster and more efficient if it is run by those who are most concerned,” said Jeanne Gapiya, who has been living with HIV for many years and runs the ANSS nongovernmental organization in Burundi.

Community-led HIV testing and prevention is effective, particularly for marginalized groups. “Most of the people tested by communities were never reached before and this shows how community organizations are unique and essential,” said Aliou Sylla, Director of Coalition Plus Afrique.

Reducing the number of new HIV infections among children and ensuring that women have access to the services they need remains one of the biggest challenges in the region. Networks of mothers living with HIV who support each other to stay healthy and help their child to be born HIV-free have been shown to be an effective way of improving the health of both mothers and children.

“Our community-based approach works. In the sites where we work we have reached the target of zero new HIV infections among children and all children who come to us are on treatment,” said Rejane Zio from Sidaction.

Financing remains a concern and although total resources for the AIDS response have increased, and HIV remains the single largest focus area for development assistance for health, domestic investments account for only 38% of total HIV resources available in western and central Africa, compared to 57% worldwide. Greater national investments reinforced by stronger support from international donors are needed to Fast-Track the regional response. Bintou Dembele, Executive Director of ARCAD-Sida, Mali, said, “We have community expertise, but we lack the funds to meet the need.”

Support is growing for community-based approaches in the region. Recognizing the importance of community-led work, Expertise France and the Civil Society Institute for Health and HIV in Western and Central Africa announced a new partnership on 9 October. “The institute brings together 81 organizations from 19 countries aiming to ensure better political influence at the global and country levels and to galvanize civil society expertise in programme delivery. This partnership is a recognition of our essential contribution,” said Daouda Diouf, Director of Enda Sante and head of the steering committee of the institute. “The situation in western and central Africa remains a priority. It is clear that community-based approaches are agile and appropriate for responding to pandemics,” said Jeremie Pellet from Expertise France.

Shifting to a people-centred approach has been at the core of reforms in the region. A growing regional resolve to accelerate the response and to strengthen community-led approaches that have been proved to work provides hope for the future of the HIV epidemic in western and central Africa.

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS and Luxembourg―working together in western and central Africa

09 October 2019

09 October 2019 09 October 2019Western and central Africa continues to lag behind the rest of Africa in preventing and treating HIV, leaving millions of people vulnerable to HIV infection and 2.4 million people living with HIV without treatment. Following calls to action made at the 2016 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Ending AIDS and the July 2016 African Union summit, UNAIDS and partners launched a plan to accelerate efforts to stop new HIV infections and ensure that everyone in the region has access to life-saving treatment.

Although resources available in western and central Africa to respond to HIV increased by 65% between 2006 and 2016, reaching an estimated US$ 2.1 billion, most countries remain highly dependent on donors. However, international funding is declining and current investment levels are far lower than what is actually needed to make a sustainable change.

Luxembourg is one country that remains committed to investing in western and central Africa. Marc Angel, Chair of the Foreign Affairs and Development Committee in the Luxembourg Parliament and UNAIDS Champion for the 90–90–90 Targets, joined UNAIDS on a recent visit to Senegal to see how Luxembourg’s contribution to UNAIDS for the acceleration of the AIDS response in western and central Africa was helping to make a difference.

Supported by funding from Luxembourg, UNAIDS and partners have established the innovative Civil Society Institute for HIV and Health in West and Central Africa. The institute acts as a coordinating mechanism for around 80 nongovernmental organizations working in the interests of people affected by HIV in 20 countries across western and central Africa.

One such group is CEPIAD, the first centre for harm reduction for people who inject drugs in western Africa. The medical staff and social assistants are pioneers in the region, treating people who use drugs with a public health approach rather than judgement. In Mbour, at the treatment centre for key populations, Mr Angel heard from people who had injected drugs in the past, who shared their personal stories of how the centre had helped them to reintegrate with their families and society.

“Only by including key populations can the 90–90–90 targets be reached,” said Mr Angel. “Senegal’s public and civil society actors have to continue working hand in hand towards this objective. For Luxembourg’s development cooperation, the human rights dimension in the fight against AIDS and in global health is key. Together with UNAIDS we need to ensure that voices from communities are being heard, working all over the country, in particular with vulnerable populations, including children.”

Mr Angel also visited the paediatric treatment ward of the Albert Royer Hospital, where he met young people living with HIV. They shared their experiences of treatment for HIV, which is allowing them to live normal lives. He noted the progress made in stopping new HIV infections among children in Senegal and the important work done around sexual and reproductive health and HIV to prevent new HIV infections among adolescents.

During meetings with the Minister of Health and Social Action of Senegal, Abdoulaye Diouf Sarr, and the Secretary-General of Senegal’s National AIDS Committee, Safiatou Thiam, Mr Angel praised Senegal for decreasing the national HIV prevalence.

However, he also highlighted areas of concern, including the high HIV prevalence among key populations, emphasizing that access to treatment for key populations was instrumental to ending AIDS by 2030. He also advocated for an increase in national resources to respond effectively and sustainably to HIV in Senegal.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

How London’s first dedicated HIV ward changed the AIDS response

03 October 2019

03 October 2019 03 October 2019Opened in 1987 by Princess Diana, the Broderip Ward at the Middlesex Hospital in London was the United Kingdom’s first ward dedicated to caring for HIV patients. UNAIDS Senior Adviser on Science, Peter Godfrey-Faussett, worked on the Broderip Ward as a newly qualified doctor and remembers it as an intense and highly emotional period.

What are your first memories of HIV?

I was finishing my medical training in London when the first reports of what would subsequently be called HIV and AIDS came out. We had no idea then of the unprecedented nature of what was happening. As a medical student approaching my final exams, my concern was to know the facts, but it was clear to me even then that many of these “facts” were not yet understood. After qualifying, I soon found myself working at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London and on the Broderip Ward at the Middlesex Hospital.

How did London’s medical professionals react to this new health challenge?

The organization of services for HIV varied in different parts of London. The staff at the sexual health clinics, or departments of genitourinary medicine, as they were called then, were establishing outpatient services with counselling, support and care for people living with HIV. But these teams were generally not well equipped to provide care for people who had to be admitted to hospital. In each hospital, a different specialist team took on the care of the ever-expanding population of people living with, and dying from, HIV. Many of those needing care had pneumonia, often caused by pneumocystis. Others had persistent severe diarrhoea, neurological problems or skin diseases, including Kaposi's sarcoma.

We had an amazing team led by Steve Semple and worked in close collaboration with the staff at James Pringle House, one of the dedicated sexual health clinics in London. Steve Semple was a respiratory physician with an expertise in the normal regulation of breathing. In other parts of London, the leaders were gastroenterologists, immunologists or infectious disease physicians.

We were all learning quickly how best to care for a wider range of infections, cancers and other conditions, all while coming to understand the social networks and behaviours of our mostly gay patients.

It must have been a difficult time

It was, of course, a hugely sad time. We could treat many opportunistic infections and provide counselling and support, but HIV was almost invariably lethal in those days and we saw so many young men, who were often at the forefront of the lively and creative communities that made London such a great city, fade away gradually or deteriorate more suddenly and die.

As a medical student and young doctor, most of the people that I had treated were reaching the end of full productive lives, but here on the Broderip Ward were people of my own age, reading the same books, going to the same operas and plays. It was often hard to remain clinically detached. I can remember so many of them so clearly. And so many of their loved ones and families.

How did the opening of the Broderip Ward change the way people were cared for?

The nurse in charge of the ward, Jacqui Elliott, was a wonderful woman. Along with Steve Semple, she encouraged us all to break the mould and provide care in a very different way. Back then, hospitals were quite old fashioned and regimented. The matron and the consultant were at the point of a huge pyramid, and often the patients were near the bottom!

Right from the start we engaged with the patients and their partners, and, where necessary, turned a blind eye to regulations. The ward was the only one in the hospital to have additional fridges full of delicious meals that people brought in for their partners, often shared with other patients and the health team!

In those days, there were payphone kiosks at the end of long cold corridors in the hospital and hospital gowns were hideous affairs that tied up loosely at the back. We were the first ward to install a phone on the nurses’ desk so that patients could make calls more easily. We encouraged people to wear their own clothes and dressing gowns and to come and go from the ward as they wished. Everyone on Broderip worked around the clock. Our parties were the ones that everyone in the hospital wanted to come to.

We were learning, and no doubt we made mistakes, but we were certainly among the first medical professionals to listen to our patients and to try to provide what they needed.

And did clinical care change?

The dedicated ward was quickly a focus for teams from all over the teaching hospital. Whenever something new or strange occurred, we had a network of the best specialists in every medical discipline. The weekly clinical meeting attracted clinicians from all over the hospital and from the other hospitals in London and elsewhere.

As a junior doctor it was terrifying having to present each complicated patient to the assembled experts and seek their inputs. But I think the medical care that our patients received was at the cutting edge. We had strong relationships with the psychosocial counselling teams and with the palliative care team, who worked hard to make dying as comfortable as possible. We were, of course, trying out new antiretroviral medicines. Many of our patients were in the early trials of zidovudine, and some patients did improve.

How did patients, their friends and families and staff on the ward cope?

Each patient was an individual with his (or occasionally her) particular relationships with friends, lovers and family. For some, however, admission to the Broderip Ward was the first time that people had acknowledged their sexuality within their family, and they were also having to deal with coming to terms with HIV and the implications of impending death. The staff on the ward had to be constantly aware of who knew what and who could meet whom. Some patients preferred their family not to know on which ward they were being cared for. One of our jobs on the ward was to facilitate disclosure and counsel patients and their partners and families as they came to terms with their situation. We also had a team of make-up artists to help camouflage the visible signs of Kaposi’s sarcoma and dieticians who aimed to optimize people’s nutrition. There was always a strong sense of camaraderie and plenty of opportunities for laughter as well as tears.

How did the United Kingdom’s approach to HIV change in the 1990s and beyond?

The arrival of increasingly effective antiretroviral therapies changed everything. Early treatments were toxic and hard to manage, with specific needs for some pills with food, some without, some needing to be kept in the fridge and some needing an alarm clock to take in the middle of the night. But they worked.

Patients in hospital began to realize that they were not going to die in the next year or two. The United Kingdom’s amazing health system, the National Health Service (NHS), and the wide network of sexual health clinics, meant that professional, high-quality care and treatment was accessible to everyone at no cost. London has always been a centre for travel and migration and the diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections were exempt from any questions about residence or immigration status. Even for hospital care, the rules could be interpreted to allow everyone to be treated.

The other huge development was that grass-root community organizations sprung up and were funded. People among the African diaspora supported each other and became more organized and vocal. Services in different parts of London catered to different population bases, so that in our hospital many of our patients were gay men, whereas in east London there was a much larger population of women, usually African. Inevitably, people's challenges reflected the social context in which they lived, as well as the gender-specific clinical aspects of HIV.

More recently, some of the systems that made the United Kingdom so open to people living with HIV have changed. Funding for the sexual health clinics and community organizations is tighter, and the restrictions on who is eligible for NHS treatment are enforced more rigorously. On the other hand, most United Kingdom cities remain vibrant, tolerant places and the gay community especially has pushed for earlier and better diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Stigma is certainly still there, but I believe most people can find a clinic and a team that welcomes and supports them through the challenges of living with HIV.

There is such an array of treatment and prevention options available today, is the HIV epidemic over in the United Kingdom?

We are making exciting progress, and each year sees a fall in the number of new HIV infections, particularly in London and the other big cities. Outbreaks will continue, recently among people who inject drugs in Scotland. Ongoing stigma and denial prevent people from all communities, and particularity the African diaspora, from getting tested and accessing effective treatment or prevention promptly.

And, of course, people need treatment for life. So even as the number of new infections falls, we will need ongoing care and support and good surveillance for many more years.

Region/country

Feature Story

The pros and cons of being small

27 September 2019

27 September 2019 27 September 2019Being small has its advantages. In most Caribbean countries, a local clinic or hospital isn’t very far away. Strong primary health-care systems and high levels of health-care access for pregnant women are at the heart of the region’s success in preventing new HIV infections among children. Seven Caribbean islands have been validated by the World Health Organization as having eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV. They range from the British overseas territory of Montserrat, with a population of 5000, to Cuba, home to more than 11 million people.

Antigua and Barbuda received its elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV validation in 2017. According to its Chief Medical Officer, Rhonda Sealey-Thomas, the Ministry of Health devised strategies to make certain that all pregnant women feel empowered and supported to start antenatal care as early as possible. The twin-island state employs a community nursing model in which district nurses conduct home visits to encourage women to go to health centres near the start of their pregnancies and to keep their appointments. The country uses its 26 community clinics to ensure that every woman had easy geographical access to antenatal care.

In the Bahamas, the Ministry of Health and the wider AIDS response are working towards validation. It was among five Caribbean countries that achieved 100% coverage for early infant diagnosis in 2018.

Nikkiah Forbes, Director of the National HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Programme at the Bahamas Ministry of Health, points to the importance of having a robust health-care system with available and free antenatal care and strong laboratories. Antenatal care is universal in the Bahamas and available at community clinics throughout the island chain. Mothers are encouraged to access care as early as possible and an HIV test is offered during the first visit. Laboratory screening is repeated at 32 weeks. Dedicated nurses ensure that all mothers and infants are retained in care and receive the additional support they need.

“You have to get out in the field if you are going to provide HIV care. We go to clinics to meet the women so we can provide support and counselling. We go into the field and test their partners. We really follow up to ensure they come to the clinic, feel comfortable and are expedited. We ensure they are getting their medication, all their labs are in and that they have nutrition support. If they don’t come to us,” one nurse explained, “we go to them.”

But a small population size also comes with challenges. For migrants, there is often the added vulnerability of standing out when accessing services. Antigua and Barbuda provides health care to all migrants. “Services in the community health clinics are free of cost. Nationality does not matter. If migrants are not afforded health care, it costs more in the long run. By protecting the health of migrants, you are indirectly protecting the health of your own population,” Ms Sealey-Thomas explained.

In the Bahamas, there are also mechanisms for Haitian migrants to access care. “We have translators that speak Haitian Creole at a one-stop-shop clinic. Translations of education materials are also available in Haitian Creole,” said Ms Forbes.

But for citizens who are members of close-knit communities, special care had to be taken to strengthen confidentiality and address stigma and discrimination in health-care settings. Throughout the region, health-care providers have received anti-stigma and discrimination training to address issues that include unconscious bias and confidentiality.

Still, in any Caribbean country the likelihood of people knowing or recognizing others where they access care is relatively high. It’s a challenge that countries must overcome in order to accelerate results across the continuum of care, for adolescents, women and men alike.

Feature Story

HIV in small island developing states

27 September 2019

27 September 2019 27 September 2019“I am not ready to share my status or disclose myself to the public. I am afraid of being isolated, stigmatized and discriminated against. For me, it’s good for only me to know my status, rather than disclose it to other people,” said Mara John (not her real name), who comes from a Pacific island and is living with HIV. Similar stories of isolation, self-stigma, poverty and lack of human rights can be heard from many people living with HIV in small island developing states (SIDS).

On 27 September, United Nations Member States meet for a high-level review on SIDS at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, United States of America. In his report published ahead of the summit, the United Nations Secretary-General highlights that SIDS, particularly Caribbean SIDS, continue to be challenged with “high levels of youth unemployment, poverty, teenage pregnancy, and high risk for HIV infection.”

A group of 38 countries, including islands in the Pacific, the Caribbean and elsewhere, the SIDS have been provided with dedicated support owing to the specific constraints they face―for example, the size of their territory, remoteness or exposure to climate change―as a result of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, also known as Rio+20, held in June 2012. In 2014, the SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action Pathway was adopted by United Nations Member States to outline actions for sustainable development in the SIDS, including a commitment to achieving universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support and to eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

While the SIDS have seen progress, there are wide differences between, for example, Cuba, the first country globally to be certified as having eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV, in 2015, and Mauritius, where 30% of people who inject drugs are reported to be living with HIV.

“The Sustainable Development Goals highlight the importance of leaving no one behind. This is particularly meaningful for people living with HIV in small island developing states, who face isolation, stigma and discrimination and inequalities. We need to do more to ensure that they receive the services they need,” said Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i.

Generally in small islands, key populations, including gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers and people who inject drugs, bear a disproportionately high burden of HIV. In some SIDS, however, HIV also significantly impacts the general population―while key populations and their sexual partners accounted for 47% of new HIV infections in the Caribbean in 2018, more than half of all new HIV infections were among the general population. Stigma and discrimination by health-care workers is still a major challenge in the Pacific. For example, 60% of female sex workers surveyed in Fiji reported avoiding HIV testing owing to fear of stigma from health-care providers, as did more than 30% of gay men and other men who have sex with men.

Another aspect that SIDS have in common is the strength of communities of people living with HIV and the presence of exceptional political will, often at the highest levels. Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, the former President of Fiji and current Speaker of the Fiji Parliament, has been speaking out against stigma and discrimination for many years.

Networks of people living with HIV and of key populations are at the centre of the movement to end AIDS in the SIDS. In the Pacific, people living with HIV came together to publish a report in 2018 describing their situation in their own words. Similarly the Mauritius Network of People Living with HIV has provided vocal leadership to the response and clearly outlines the challenges of the community in its 2018 People Living With HIV Stigma Index report. In the Caribbean, the late activist and academic Robert Carr is credited for helping to shape global thought around the importance of addressing the human rights of vulnerable and marginalized communities as part of the AIDS response. In 2005, he helped to establish the Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition, which works on behalf of the groups most often left behind.

UNAIDS is working to support SIDS through its team for the Caribbean, based in Jamaica, for the Pacific islands from its Fiji office and for the Indian Ocean islands from the UNAIDS office in the Seychelles. Priority is given to SIDS with a higher prevalence of HIV, through programmes targeting the most vulnerable populations.

Small Island Developing States

Related

Feature Story

Without sustainable financing the AIDS response will fail

26 September 2019

26 September 2019 26 September 2019This week, the United Nations General Assembly committed itself to achieving universal health coverage by 2030. It also pledged to accelerate efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, including ending AIDS, by 2030. Those commitments show that there is political will to respond to the gravest crises facing the world.

In 2016, the General Assembly agreed, in the Political Declaration on Ending AIDS, to a steady scale-up of investment in the AIDS responses in low- and middle-income countries, increasing to at least US$ 26 billion by 2020. At the end of 2018, however, only US$ 19 billion (in constant 2016 US dollars) was available. And, worse, that US$ 19 billion was almost US$ 1 billion less than a year before.

Instead of a steady increase, global financing for HIV is decreasing. The political commitment is simply not being matched with the financing required to turn the vision of an end to AIDS into reality. With a little more than a year to go until the 2020 target of US$ 26 billion, finance for the AIDS response falls short by US$ 7 billion. This shortfall is particularly alarming because we know that investments in the AIDS response save lives―investing in the AIDS response is a great investment.

“The world can’t afford to backslide on investment in the AIDS response,” said Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i. “Countries must honour their pledge to steadily increase their investment in the response to HIV if the world is to meet its obligations to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged.”

Funding declines were seen in all sectors in 2018: domestic resources (a 2% decline), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) (a 20% decline, explained by fluctuations in its three-year grant cycle), other multilateral channels (a 2% decline), the Government of the United States of America’s bilateral programmes (a 3% decline), the bilateral programmes of other donor countries (a 17% decline), philanthropic organizations (an 18% decline) and other international sources (a 4% decline).

Low- and middle-income countries are increasingly financing their AIDS responses themselves. Between 2010 and 2018, domestic resources invested by low- and middle-income countries in their AIDS responses increased by 50%, while international investments increased by just 4%.

Domestic financing in 2018 in low- and middle-income countries accounted for 56% of total financial resources, although there were wide variations among regions. In eastern and southern Africa, the region with the highest HIV burden, 59% of HIV resources came from donors in 2018―this rises to 80% if South Africa is taken out of the analysis. Between 2010 and 2018, all major donors except the United States reduced their bilateral direct contributions to the AIDS responses of other countries.

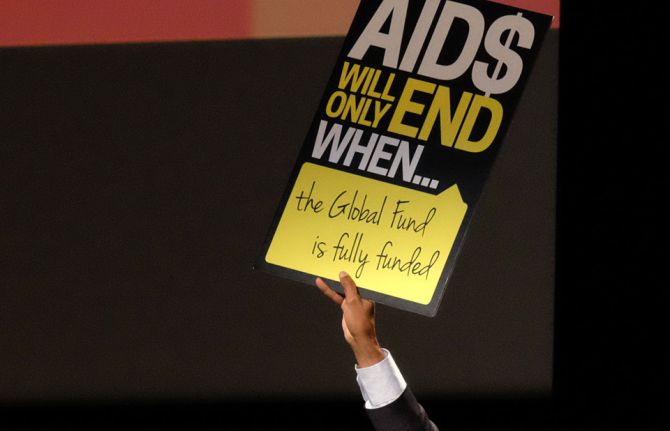

This October is a critically important time for finance and HIV. In Lyon, France, on 10 October, governments and other partners will meet for the Global Fund’s sixth replenishment pledging conference. Seeking to raise at least US$ 14 billion for the response against HIV, tuberculosis and malaria for 2020–2022, the Global Fund estimates that 16 million lives will be saved by its programmes if fully funded, building on the 27 million lives saved since its inception in 2002.

“I urge countries to fully fund the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in its upcoming replenishment―16 million men, women and children are counting on it,” said Ms Carlsson.

Related information

Feature Story

Communities of faith―helping to find the missing men and seeking justice for children

26 September 2019

26 September 2019 26 September 2019Bobby was born in 1996 in the small, mountainous country of Lesotho. His mother was living with HIV, and, unknown to him, he was born with the virus. He lost his little brother when he was just four years old and his little sister when she was just six to meningitis—a devasting blow to Bobby. Life was hard, and at 12 years old he received news that was to change his life forever. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis and found out that both his mother and father were living with HIV.

But Bobby didn’t give up. “Some people wanted to break me, but they only made me stronger. Some people wanted to exploit me, but they only made me smarter,” said Bobby. “Taking pills and going from an HIV-positive child to an HIV-positive activist has not been easy. I faced a lot of stigma and discrimination. But one of my biggest dreams is to live and to contribute, which is why I’m here today.”

On 26 September, Bobby shared his journey with an audience of more than 150 faith leaders and partners working on HIV at the Communities of Faith Breakfast, held at the Yale Club, on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York, United States of America.

Bobby’s story and the thousands of others like his have inspired faith groups around the world to take action to stop new HIV infections and support people living with and affected by the virus. Speaking at the event, the Minister of Health of Zambia, Chitalu Chilufya, shared how faith leaders in his country are playing an important role in improving the health and well-being of their congregations, particularly by reaching men.

“We have several ministers that hold health Sundays, bringing in doctors to engage their congregation on health matters,” said Mr Chilufya. “Men are in the marketplaces and men are in the churches—and this is how we are reaching them. Through these efforts we have seen the percentage of men who have not been tested for HIV reduce from 50% to 30%.”

The importance of reaching men was echoed by many of the speakers, as was the urgent need to ensure that children have access to optimal HIV services and justice.

“In 2018, we lost 100 000 children to AIDS-related deaths and only 54% of the 1.7 million children living with HIV worldwide were accessing treatment. These are very sad statistics,” said Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i. “Engagement of faith-based health partners will be critical to help governments transform their commitments on HIV into real action on the ground.”

The breakfast provided a space for partners to come together and share ideas and experiences of innovative approaches to reach young men, adolescent girls and young women and children living with HIV with HIV prevention and treatment services. It also fostered positive discussions on how to prevent and respond to sexual violence against children, which significantly increases their risk of HIV infection.

“Our discussions here will shed light on what is possible and once we know what is possible there is no excuse to make it possible for everyone, everywhere, at all times,” said Deborah Birx, United States Global AIDS Coordinator and Special Representative for Global Health Diplomacy.

Related

Feature Story

Young people taking action, inspiring change

25 September 2019

25 September 2019 25 September 2019Around 19 000 inspirational young people gathered at WE Day UN on 25 September to celebrate the incredible work they are doing to make positive change in their communities and around the world. All the young people who attended the event had earned a free ticket by taking action on one local and one global cause of their choice. Taking place in New York, United States of America, during the seventy-fourth session of the United Nations General Assembly, this year’s WE Day UN was held in partnership with UNAIDS, the UN Global Compact and UN Women.

UNAIDS has enjoyed a long-standing partnership with WE Day, helping to educate young people about HIV and to support them in their socially conscious efforts to make a sustainable impact in their societies and around the world. Through the important work of WE Day, UNAIDS is able to reach more than 20 000 schools across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada.

Speaking to the young audience in the Barclays Center Stadium in New York, Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i., said, “AIDS is not over, but it can be! You can be the generation that ends AIDS and leads the world in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, creating a better world for generations to come.”

Ms Carlsson used the opportunity to remind young people of the importance of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and how critical it is to talk about HIV to break down the stigma around the epidemic. Her remarks were preceded by a newly released animation from UNAIDS that demonstrates the interlinkages and interdependence of HIV and the Sustainable Development Goals and how efforts to end AIDS can lead to a wider, people-centred social transformation.

Related

“Who will protect our young people?”

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025