Feature Story

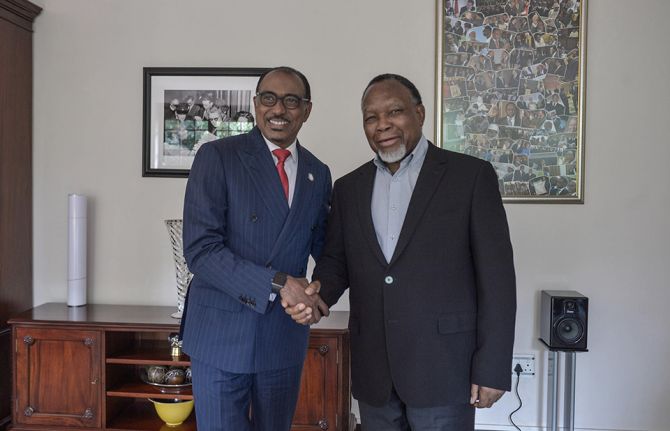

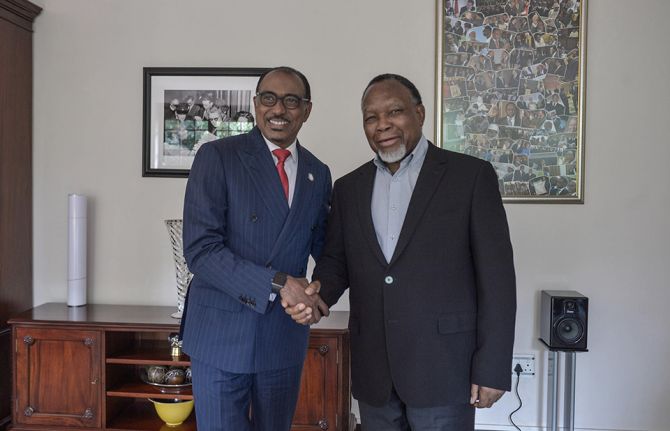

UNAIDS Committee of Cosponsoring Organizations meet

06 April 2009

06 April 2009 06 April 2009

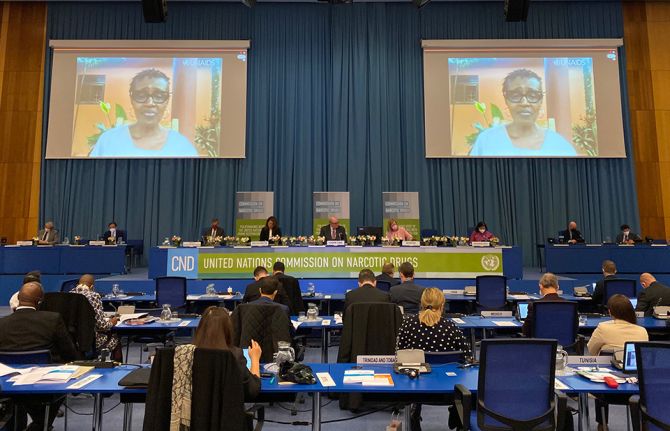

(from left): Joy Phumaphi, Vice President and Head of the Human Development Network, World Bank; Arnauld Akodjenou, Director, Division of Operational Services, UNHCR; Josette Sheeran, Executive Director, WFP; Anarfi Asamoa-Baah, Deputy Director General, WHO; Assane Diop, Executive Director, Social Protection Sector, ILO; Koichiro Matsuura, Director General, UNESCO; Ad Melkert, Administrator ad-interim, UNDP; Ann M. Veneman, Executive Director, UNICEF; Michel Sidibé, Executive Director, UNAIDS; Thoraya Ahmed Obaid, Executive Director, UNFPA; Antonio Maria Costa, Executive Director, UNODC. Paris, 3 April 2009,

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) brings together the efforts and resources of ten UN system organizations in the AIDS response. The UNAIDS Committee of Cosponsoring Organizations (CCO) serves as the forum for these Cosponsors to meet on a regular basis to consider matters of major importance to UNAIDS, and to provide input from the Cosponsoring organizations into the policies and strategies of UNAIDS.

On 3 April 2009, the CCO held their first meeting since the appointment of UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé.

The CCO expressed their full support for “universal access” which Mr Sidibé has outlined as the top priority for UNAIDS as well as the other priority areas of focus which will be set out in the new UNAIDS outcome framework currently being finalized with Cosponsors.

The meeting provided an excellent opportunity to share ideas on supporting countries in achieving their universal access goals. The need for UNAIDS to advocate for an evidence informed AIDS response that is grounded in human rights was accepted by all. Equally important was the need for accountability and results.

The CCO also endorsed the general directions of the 2010-2011 Unified Budget and Workplan including the key priorities and the allocation of resources between the Cosponsors, the Secretariat and Interagency activities. The Secretariat will now work with the Global Coordinators of the Cosponsors to finalize the UBW for the June 2009 meeting of the Programme Coordinating Board.

UNAIDS Committee of Cosponsoring Organizations (CCO)

The CCO comprises representatives from the ten UNAIDS Cosponsors and the UNAIDS Secretariat. It meets twice a year and each Cosponsor rotates as chair of the committee annually, on 1 July.

Right Hand Side

Cosponsors:

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)

World Food Programme (WFP)

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

International Labour Organization (ILO)

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

World Health Organization (WHO)

World Bank

Related

Keeping up the momentum in the global AIDS response

Keeping up the momentum in the global AIDS response

24 April 2019

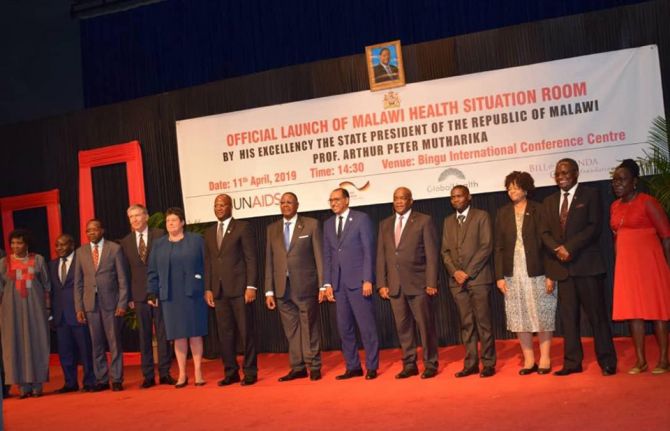

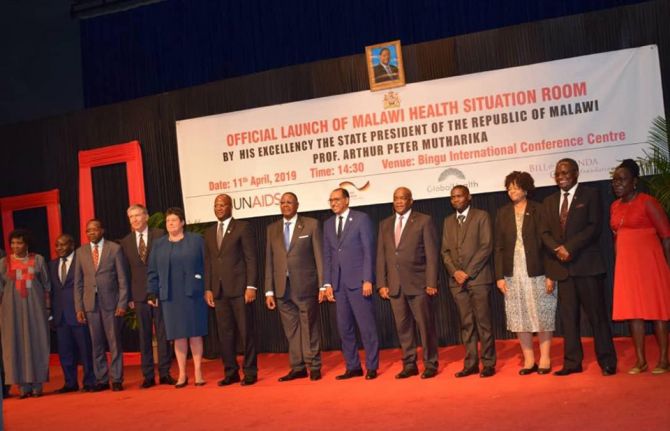

Malawi launches its health situation room

Malawi launches its health situation room

12 April 2019

Learning lessons on evaluation

Learning lessons on evaluation

02 April 2019

Feature Story

Injecting drug use and HIV: Interview with UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care and Support team

12 March 2009

12 March 2009 12 March 2009The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) is meeting at the United Nations Office in Vienna for its 52 session, from 11-20 March 2009. At this session, governments will assess the progress achieved in meeting the goals defined in the 1998 UN General Assembly Special Session on Illicit Drugs.

In an interview, Mr Michael Bartos, UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care and Support team, shares his thoughts on the Commission’s progress in addressing the link between injecting drugs and HIV.

The 52nd session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs is taking place 11 years after the landmark UN General Assembly Special Session on Illicit Drugs in 1998. Where are we today in addressing the links between HIV and drug use?

This year’s session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in Vienna marks ten years plus a year of reflection since the 1998 UN General Assembly Special Session on Illicit Drugs. The Commission and its high-level ministerial segment will be looking at progress made since 1998, the current situation and the next steps in the response to the global drug problem.

HIV is only one of the many aspects of the global drug problem. At the CND it is considered in the context of “demand reduction” where members will consider how to deal with both direct harms to drug users and the associated harms which include HIV.

"We are now very well aware of the central link between HIV and injecting drug use, and aware that the nexus has to be broken if we’re really to have any hope of getting HIV as an epidemic under control in many parts of the world."

Michael Bartos, UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care and Support team

Since 1998 we have become much more conscious of the intertwined nature of the epidemics of drug use and HIV. In 1998 we were already able to see the extent to which HIV had been transmitted among injecting drug users, and we were aware of the fact that injecting drug use was a very efficient way for HIV to spread across the countries. But at that stage the extent of the potential problem was not yet fully in view. For example the Russian HIV epidemic —which is largely driven by injecting drug use— had very few HIV cases before the beginning of the 90s. We now talk about Russia having one million HIV cases. The reality is that the decade of the 90s saw the explosive growth of HIV amongst injecting drug users in Russia and in a number of other countries.

So we are now very well aware of the central link between HIV and injecting drug use and aware that the nexus has to be broken if we’re really to have any hope of getting HIV as an epidemic under control in many parts of the world.

What are some of the key challenges in responding to the issues of HIV and drug use?

There are a series of challenges to properly addressing HIV amongst injecting drug users. The first is that in most countries injecting and other drug use are illegal. Therefore these behaviours and the ways they are controlled fall under the authority of the police.

This is an issue in relation to HIV as the most effective prevention strategies are those which include the people who are most affected. It has been very difficult for people who inject drugs to argue that they can, should, and indeed must, be part of the solution to AIDS and not viewed simply as part of the problem and thrown into prison or treatment camps.

Injecting drug users can find themselves marginalized in most social responses, including the responses to HIV. A considerable challenge is how to assist people who use drugs access HIV services and how to assist organizations who help provide services to people who use drugs, including HIV services.

Can law enforcement agencies and AIDS organizations work together?

Some real achievements have been made when law enforcement authorities and people who use drugs have found a common cause working together to deal with the harms associated with injecting drug use. That’s one of the things that we need to focus on: the ways in which positive policing can support AIDS response.

What will UNAIDS highlight at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs?

At the Commission on Narcotic Drugs UNAIDS wants to draw attention to the scale of the problem. There is virtually no country in the world where there aren’t at least some people who inject drugs. Recent estimates, constructed under the auspices of the reference group to the United Nations system on injecting drug use, show around 16 million drug users across the world, an estimated 3 million are living with HIV. That’s quite a considerable part of the global HIV epidemic. In fact 30% of the global HIV epidemic outside sub-Saharan Africa is among injecting drug users.

"Many IDUs are excluded from HIV treatment programmes because those running the programmes assume that people who use drugs would be unable to take their HIV treatment regularly."

Michael Bartos, UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care and Support team

But even more important than drawing attention to the scale of the problem is moving the focus to the scale of the response needed. A number of countries around the world are moving to full scale implementation of harm reduction services to deal with HIV amongst people who inject drugs.

These services include access to opioid substitution therapy such as methadone and buprenorphine services as a way drug users can be assisted to deal with their addiction. Other services include access to drug treatment and sexual health services, condoms and access to antiretroviral therapy for HIV for those drug users who need it.

Many IDUs are excluded from HIV treatment programmes because those running the programmes assume that people who use drugs would be unable to take their HIV treatment regularly.

Needle and syringe exchange services have proven to be effective in ensuring that drug injectors do not share contaminated equipment—which is a very efficient way of passing on the virus.

A number of countries are scaling up access to this full range of services. Impressive work has been done by countries such as Indonesia. Malaysia has made high level commitments to address these questions among its population. China has been very seriously addressing the way in which can fully scale up its package of services in relation to HIV and injecting drug use. The same has applied to many parts of India, and Bangladesh which have also made some impressive commitments. So particularly in east and south-east Asia there have been some strong developments. Also In eastern Europe and central Asia there have been signs that the most successful national responses to HIV amongst IDUs are looking to provide these services at full scale.

Do you anticipate the Commission on Narcotic Drugs at this session to make some headway on harm reduction? What needs to be done, politically speaking, to get harm reduction on Member States’ agenda?

"It has been very difficult for countries around the world to get the right balance—or to come to consensus on how to balance— the twin desires of getting people to not use drugs and also reducing the harms associated with drug use."

Michael Bartos, UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care and Support team

The Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS adopted by the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS in 2001 makes a clear commitment to the range of harm reduction approaches. This was then repeated by the General Assembly in its 2006 Political Declaration on AIDS. However, the phrase “harm reduction” in the context of “drug control” which is reflected in the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, remains a contested term.

Apart from a question of terminology, harm reduction is also contested on a substantive level. It has been very difficult for countries around the world to get the right balance—or to come to consensus on how to balance— the twin desires of getting people to not use drugs and also reducing the harms associated with drug use.

I think that there is a strong sense across the world that a public health approach, a harm reduction approach, is the more prominent perspective in the global discourse. However it still hasn’t found its expression in the policies of a number of countries.

We have a situation where in some countries the national drugs authorities who consider questions of drug use and HIV may not even know what their counterparts in the national health and AIDS authorities are doing in relation to their response to HIV amongst IDUs.

One of the priorities for UNAIDS, alongside United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) which is our lead cosponsor on these issues, is to actually bring together drug authorities, AIDS authorities and prison authorities to talk jointly about the strategies which they are adopting to identify jointly what the barriers are to effective strategies for dealing with these intertwined problems in their settings such as prisons, or in relation to street policing, or in relation to HIV services and health services.

Back to topInjecting drug use and HIV: Interview with UNAIDS Team Leader, Prevention, Care

Cosponsors:

Press centre:

High Commissioner calls for focus on human rights and harm reduction in international drug policy (10 March 2009)

Feature stories:

OPINION: Silence on Harm reduction not an option (11 March 2009)

51st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (11 March 2008)

Reducing drug related harm (14 May 2007)

Injecting drug use: focused HIV prevention works (11 May 2007)

Harm reduction to be scaled up in Ukraine (11 April 2007)

Increased HIV services for drug users needed (14 November 2006)

External links:

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND)

Statements:

Publications:

Best Practice Publication: High Coverage Sites—HIV Prevention among Injecting Drug Users IDU in Transitional and Developing Countries ( En | Fr | Es | Ru )

Feature Story

OPINION: Silence on harm reduction not an option

11 March 2009

11 March 2009 11 March 2009

Today of the estimated 16 million people world wide who inject drugs—3 million are HIV positive. Any discussion on drugs cannot ignore their needs and human rights.

Credit: UNAIDS

In 1998, the UN General Assembly held a Special Session on the world drug problem. At the time there was little discussion on the linkage between HIV and drugs. Today of the estimated 16 million people world wide who inject drugs—3 million are HIV positive. Any discussion on drugs cannot ignore their needs and human rights.

Over the years the issue of HIV and drug use (especially injecting drug use) has grown. However, the global response has not followed the scientific evidence and harm reduction has been largely excluded.

Harm reduction programmes include access to sterile injecting equipment, opioid substitution therapies, condoms, STI treatment, information on sexual transmission of HIV and community-based outreach. These are the most cost effective means of reducing HIV related risk behaviors. They not only prevent transmission of HIV but also of hepatitis C and other blood borne viruses.

The word “only” hasn’t worked for HIV prevention, treatment, care and support programmes. And the evidence shows that programmes that “only” focus on one area of drug use will not work either.

Too often countries have taken the one dimensional approach of reducing drug demand or supply. The word “only” hasn’t worked for HIV prevention, treatment, care and support programmes. And the evidence shows that programmes that “only” focus on one area of drug use will not work either.

Countries that have adopted a comprehensive approach to HIV and drug use have seen a slowing and reversal in the spread of HIV among people who inject drugs. This includes countries such as Australia, UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Brazil, and in some cities in Bangladesh, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine. In recent years countries such as Indonesia and China are scaling up access to harm reduction programmes for injecting drug users.

No evidence has been found of unintended negative consequences such as increased initiation, duration or frequency of injecting drug use. On the contrary it has been found that countries which have adopted this public health approach to HIV prevention among people who inject drugs have been the most successful in reversing the HIV epidemic.

In contrast to the overwhelmingly beneficial effects of harm reduction, law enforcement approaches alone do little to reduce drug use and drug-related crime and are often associated with serious human rights abuses and poor health outcomes for people who use drugs. They include arbitrary arrests, prolonged detention, compulsory drug registration and unwarranted use of force and harassment by law enforcement officers. Drug laws may make possessing and distributing sterile needles and syringes an offence, and opioid substitutes may be classified as illegal, despite both methadone and buprenorphine being on the WHO model list of essential medicines.

It should not be a crime to access clean needles. It should not be a crime to access substitution therapy.

These measures reinforce stigma against people who inject drugs, create disincentives to accessing services (including treatment for drug dependence or HIV) and may make health and welfare professionals wary of offering services to people who use drugs. But when law enforcement and public health efforts come together, the outcomes are very successful– for example in Britain and Australia where drug action teams police focus on the crime fighting and successfully refer drug users to health and welfare services. It is time to come together, not work against each other.

It should not be a crime to access clean needles. It should not be a crime to access substitution therapy. The global drug problem is complex and cannot be solved in isolation. A coming together of organizations working on drug control and AIDS is urgently needed. Working together the world has a better chance to employ solutions that save lives.

The largest numbers of HIV positive people who inject drugs are in Eastern Europe, East and Southeast Asia and Latin America. HIV prevalence among some groups in these regions is estimated at over 40%. New epidemics of injecting drug use are also emerging in sub-Saharan Africa. HIV can spread extremely quickly once it enters a population of people who inject drugs. Increases in HIV prevalence from 5% to 50% in one year have been observed among people who inject drugs in some settings, and HIV can also spread from people who inject drugs to their sexual partners and other populations at higher risk of HIV exposure.

Right Hand Content

Cosponsors:

Press centre:

High Commissioner calls for focus on human rights and harm reduction in international drug policy (10 March 2009)

Feature stories:

51st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (11 March 2008)

Reducing drug related harm (14 May 2007)

Injecting drug use: focused HIV prevention works (11 May 2007)

Harm reduction to be scaled up in Ukraine (11 April 2007)

Increased HIV services for drug users needed (14 November 2006)

External links:

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND)

Statements:

Publications:

Best Practice Publication: High Coverage Sites—HIV Prevention among Injecting Drug Users IDU in Transitional and Developing Countries ( En | Fr | Es | Ru )

Related

Feature Story

ICASA 2008: HIV in prison settings

06 December 2008

06 December 2008 06 December 2008

(from left) Sylvie Bertrand, UNODC Regional Programme Coordinator HIV and AIDS in Prison Settings - Southern Africa; Dr Johnson Byabashaija, Commissioner General Uganda Prisons Service

Credit: UNAIDS/Mamadou Gomis

“If we do not implement adequate measures to prevent HIV infection in prisons, people incarcerated will always be vulnerable to the disease,” said Mr Gallo Diop, a former prisoner and AIDS advocate from Senegal.

Mr Diop was speaking on Friday 5 December at an ICASA session organized by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) titled “HIV and AIDS prevention, care, treatment and support in prison settings”.

He emphasized that the movement of people in and out of prisons is also contributing to the spread the virus among those outside of prison settings.

Session participants analyzed the impact that HIV is having inside African prisons and there was consensus that addressing HIV situation in prisons is a key component of effective responses to AIDS.

Overcrowded prisons with poor facilities and sanitary conditions combined with a lack of HIV prevention services, health care and adequate nutrition are contributing to the spread of the virus argued participants. They identified the need for more data and research to identify the nature and patterns of risky behaviours.

Brian Tkachuk, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Regional Advisor for HIV and AIDS in prisons - Africa

Credit: UNAIDS/Mamadou Gomis

“There is still a knowledge gap in understanding the magnitude of the epidemic in African prisons and its multiplier effect on the non-prison population in the region,” said Brian Tkachuk, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Africa Regional Advisor for HIV and AIDS in prisons during his presentation.

In order to mitigate the impact of HIV in prisons, Mr Tkachuk highlighted the need to raise awareness of HIV among prisoners, promote peer education and provide access to prevention interventions like availability of condoms, safe tattooing and injecting equipment, and access to private visits with partners. He also underscored the need to provide access to HIV treatment and adequate nutrition for prisoners living with HIV.

Mr Tkachuk noted that “the HIV situation in prisons remains a highly neglected area that needs immediate attention,” and he called for the adding of HIV in prisons into National AIDS responses.

“You can never succeed in addressing the AIDS situation in prisons if you don’t have total political commitment,” said Dr Johnson Byabashaija, Commissioner General Uganda prisons Service. At the same time, he emphasized, there is a need to establish strong information management systems to collect qualitative data for the development of focused advocacy and HIV prevention programmes for prison settings.

ICASA 2008: HIV in prison settings

External links:

Official web site of ICASA 2008

Multimedia:

Interview with UNODC Africa Regional Advisor for HIV and AIDS, Brian Tkachuk

Feature Story

Making a difference: UNAIDS in Iran

13 May 2008

13 May 2008 13 May 2008

Hamid Reza Setayesh is UNAIDS Country

Coordinator in Iran.

HamidReza Setayesh became the UNAIDS Country Coordinator (UCC) when the UNAIDS Iran office was established in March 2005. Like most UNAIDS Country Coordinators Setayesh’s time is filled with the major task of coordinating the UN response on AIDS in the country. In Iran there are 13 UN offices that make up the Joint UN Team on AIDS, which he chairs. In addition to this, the UNAIDS office also provides technical support to the government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as it is considered a trusted and reliable partner.

“Our greatest achievement has been the harmonisation of the UN response to AIDS,” says Setayesh. “We were able to move forward and I am very satisfied with that.” Other important achievements in his three years of office are in the area of improving strategic information, where the country lacks sufficient capability. UNAIDS has assisted the government in designing small studies which provide the evidence for successful interventions.

The major factor which is fuelling the epidemic in Iran is the use of contaminated injecting equipment among injecting drug users, as well as sexual transmission of the disease. Therefore, the work of the Joint UN Team on AIDS is primarily focused on the issue of injecting drug use, “It is our top priority to advocate with the government to allocate resources towards harm reduction interventions,” says Setayesh. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), there are an estimated 200,000 injecting drug users in the country, considerable proportion of whom are using crystal-base heroin which is known in the market as “crack”.

This work has been successful and the Iranian government has one of the most progressive harm reduction policies on record in a developing country. There are more than 20,000 drug users on the government methadone maintenance programme, which began three years ago. Important legal reforms have facilitated the success of this programme: although drug use is a crime, people who are having treatment for drug use are not considered criminals. “Even needle and syringe programmes can be considered treatment, which is a very big achievement and an important step to de-stigmatise and make services available to people who inject drugs,” says Setayesh. Based on the most recent available studies, more than 90 percent of drug users have used clean needles for their last injection in Tehran.

Two years ago the drug treatment programme was extended to prisons where the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is the main partner. “A lot has been done but there is room for improvement,” says Setayesh. “Prison systems are trying to introduce needle exchange and condoms, but it is a challenge to encourage the prisoners to use them. This requires reform to expand services in prisons. “

Nonetheless, Iran is moving from having a concentrated HIV epidemic among injecting drug users to a more generalized situation, mainly affecting partners and wives of people who inject drugs and people formerly in prison. Although the response among these particular key populations has been remarkable and progressive, other groups who engage in risky behaviour such as sex workers and men who have sex with men are not sufficiently addressed in the country's response. Homosexuality is a sensitive issue in Iran and providing services for men who have sex with men presents many challenges for UNAIDS, which is the leading UN programme in this area.

As in many other countries, it is stigma that is the major obstacle to the AIDS response in Iran. “This is found at different levels,” says Setayesh, “although we get a lot of support from communities, from government and partners, it is still a challenge.”

There is also difficulty in getting funding for innovative ideas to challenge stigma. “Though the government is committed, they spend a lot of money on methadone substitution and harm reduction. When you want to work with other groups, the government is less interested and there is no donor support,” says Setayesh. “Radio and television are not that interested in openly addressing stigma, particularly with regard to sexual transmission. They are much better with drugs.”

The Joint UN Team has worked on identifying major sources of stigma and on a novel approach to combat it. They approached high level religious leaders who supported the principle that people living with HIV should not be discriminated against and that public funds should be allocated for their health care. “This helped people living with HIV to express themselves and has put a face to HIV.” In addition, a new strategy, “Positive Prevention” is being developed by National AIDS Programme through supports from UNAIDS and UNDP.

Setayesh is upbeat about the prospects for Iran’s AIDS response. “I think everything is possible in this country,” he says. “It’s very progressive in many aspects, and the government’s work is based on evidence. That provides a very good opportunity for us to convince policy-makers to do more for public health.” With these attitudes Setayesh believes it may be possible to turn the epidemic around. There is already evidence that the methadone substitution programme is having an impact, with decreased prevalence in prisons. “We hope to see results in two years time,” he says. “And that will remarkably affect the community outside because of the linkages between drugs and sex work. So this is a golden opportunity that has already been used and I hope continues.”

Making a difference: UNAIDS in Iran

Feature stories:

Making a difference: Jamaica (14 March 2008)

Making a difference: UNAIDS in Ethiopia (8 February 2008)

Making a difference: UNAIDS in Ukraine (8 January 2008)

Addressing HIV and drug use in the Middle East and North Africa (03 November 2006)

Publications:

Middle East and North Africa Regional Summary 2007 AIDS epidemic update (pdf, 175K)

Related

Feature Story

51st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs

11 March 2008

11 March 2008 11 March 2008

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) met for its 51st session in Vienna 10-14 March 2008. At this session governments assessed the progress achieved in meeting the goals defined in 1998 UN General Assembly Special Session on Illicit Drugs.

UNAIDS delivered a statement to the 51st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (Vienna, 10-14 March), calling for increased investment and programmatic action to provide prevention, treatment and support and to protect the human rights of people who use drugs. Read the UNAIDS statement.

The findings of the session will serve as a report to the UNGASS in 2009, together with an identification of future policy-oriented priorities and further actions beyond 2009.

Monitoring the outcome of the 1998 General Assembly Special Session on countering the world drug problem

The 1998 UN General Assembly Special Session on Illicit Drugs (UNGASS) concluded with member nations adopting a political declaration where ambitions and actions for the next decade were outlined. Among other things the declaration said that participating governments commit themselves to “achieving significant and measurable results in the field of demand reduction by the year 2008”.

The United Nations has started a process to assess the results of the international efforts to combat illicit drugs and to review the international conventions on narcotic drugs. The process will be completed with a special session of the UN General Assembly (UNGASS) in New York in 2009.

51st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Related

Related

HoA

04 August 2014

unodc web

04 August 2014

HIV in Libya: New evidence and evolving response

HIV in Libya: New evidence and evolving response

28 June 2012

Related

HoA

04 August 2014

unodc web

04 August 2014

HIV in Libya: New evidence and evolving response

HIV in Libya: New evidence and evolving response

28 June 2012