Asia Pacific

Feature Story

“I’ve saved lives on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic in China”

28 April 2020

28 April 2020 28 April 2020The winter of 2019/2020 in Wuhan, China, will remain with Xiao Yang for the rest of his life. During 60 days working in a makeshift hospital as an emergency nurse, he saw life and death, happiness and sorrow, tears and laughter.

Mr Xiao volunteered to go to Wuhan from his home town, Beijing, to save lives. “Saving life is the responsibility of every medical worker,” he said. This commitment is deeply rooted in his family—17 years ago, his father worked as a doctor on the frontline of the SARS epidemic.

Mr Xiao didn’t tell his boyfriend he was going to Wuhan until the last minute. “He didn’t want me to go, but he respected my decision,” he said.

On the night of their arrival in Wuhan, the volunteers were divided into two groups—intensive care and mild cases.

Mr Xiao was assigned to intensive care. For his protection, he was required to wear five gloves and two masks. However, most of the gloves were too small for him—wearing them for more than 20 minutes hurt. He also found it difficult to breathe. “It felt like someone was covering my mouth all the time,” he said.

Even worse for Mr Xiao is that he is asthmatic. If an asthma attack struck, he wouldn't have time to reach his medicine because of all the protective equipment he was wearing.

“All of us medical workers recorded final words for our families on our phones,” he said.

His boyfriend, Lin Feng, is a policeman. He too has become a lot busier because of the COVID-19 pandemic. When COVID-19 first broke out in Beijing, he was on duty for long hours, inspecting the freeways, streets and residential areas.

When the couple were far apart, instant messaging was the only way to communicate. Covered in snow after finishing his night shift, he received a text message from Mr Xiao reminding him to put on thicker clothes. His reply: “You take care of your patients. I’ll take care of you.”

Six days after his arrival in Wuhan, Mr Xiao realized that death could be near.

As he made his way around the ward, he saw a patient suffering from a drastic drop of blood oxygen level and shortness of breath. He rushed to intubate him—the quickest and most effective way to keep him alive. But he acted too forcefully, his protective suit tearing at his back—a colleague taped up the hole so he could continue to work.

After the patient was stabilized, Mr Xiao could hardly breathe and he felt sharp pains in his hands, ears and face—he had worn masks, gloves and his protective suit for too long. When the pain subsided, fear came over him. That leak could easily have seen him become infected with the new coronavirus. The leak also reminded him of the risks he was facing every day. “I can only pray I will be fine,” he said. “I was prepared for the worst when I decided to come here.”

There are many people from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex community, like Mr Xiao and Mr Lin, who worked hard to contain the virus and save lives during the pandemic. In the Wuhan Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Center, 26 volunteers worked around the clock to deliver medicine to people living with HIV. UNAIDS was proud to support their efforts by connecting the centre with local health authorities to facilitate the delivery of medicine, helping with the delivery of medicine for Chinese people living with HIV overseas and supporting the establishment of a hotline providing counselling services for people living with HIV. As a result, the centre was able to deliver medicine to more than 2600 people, and the hotline reached about 5500 people.

“It was planned that I would stay for one week, but then it was extended to three weeks and then longer,” Mr Xiao said, choking back his tears.

He finally left in early April, when the COVID-19 pandemic subsided in the city. He said he will remember everything, but he doesn’t want to relive it. Nobody should.

Now safely back with his boyfriend in Beijing, he remembered the captain’s words on his flight to Wuhan, “The flight is from Beijing to Beijing, with a stopover in Wuhan. When you have won the battle, we will take you back home.”

Resources

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

“We must ensure that HIV treatment adherence is not compromised”—keeping people in Pakistan on HIV treatment

29 April 2020

29 April 2020 29 April 2020It was a rainy night when Asghar Satti, the National Coordinator of the Pakistan Association of People Living with HIV (APLHIV), went home after spending a busy day at the office.

That day, he had received a call from a man in Karachi, Pakistan, who is living with HIV. He was worried that he was running low on his supply of antiretroviral therapy, with only nine days of treatment left. That call was one of many such calls that he had received since the beginning of the lockdown put in place after the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Pakistan in late February.

“We need to do something that really benefits the community, we must ensure that HIV treatment adherence is not compromised,” Mr Satti thought.

In order to do just that, the APLHIV set up its Emergency Response Cell (ERC) in March. The ERC is working to ensure that everyone on HIV treatment gets an adequate supply of antiretroviral therapy, often delivered to their door.

Developed by the APLHIV, together with UNAIDS and Pakistan’s National AIDS Control Programme Common Management Unit for AIDS, TB and Malaria, the ERC’s Costed Contingency Plan groups all people living with HIV who are on treatment into three groups: red (people with a supply of antiretroviral therapy for less than two weeks); yellow (people with a supply of antiretroviral therapy for a month); and green (people with a supply of antiretroviral therapy for more than a month). These groups are then used to prioritize who receives packages of antiretroviral therapy, provided by the National AIDS Control Programme, through APLHIV and the Provincial AIDS Control Programme. The National AIDS Control Programme, through its Procurement and Supply Management Unit, provides packages of antiretroviral therapy to APLHIV, which are delivered by APLHIV through courier services to the doorsteps of people living with HIV who are unable to reach treatment centres.

As well as ensuring HIV treatment, other services provided by APLHIV include education for people living with HIV and key populations on COVID-19—more than 70 000 short messages in the local language on how to prevent COVID-19 were sent during the first four weeks of the lockdown. APLHIV, in close collaboration with the Provincial AIDS Control Programme, is also monitoring the 45 centres nationwide that provide antiretroviral therapy, checking that they have sufficient stocks of treatment and that people living with HIV are being provided with services without stigma and discrimination.

With a grant from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, APLHIV has provided nutritional support to more than 3200 people living with HIV in need. “You can never imagine what this support means to me, when I don’t have a single penny to feed myself or my siblings. The help we reached is a blessing from God,” one of the recipients said.

APLHIV, which has more than 15 000 people living with HIV from across Pakistan in its network, has also linked around 4000 people living with HIV with one of the social protection programmes launched by the government to support people in need during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“APLHIV will continue operating the Emergency Response Cell until the COVID-19 pandemic ends in the country,” Mr Satti said.

“Working with the community with APLHIV is always fulfilling. The work almost always centres around finding local solutions to effectively respond to the evolving needs of the people, of the community. It is not always easy, but with constant dialogue, innovative ideas are born and then nurtured. This multimonth antiretroviral therapy dispensing and the simple use of different colours to depict level of antiretroviral therapy available, which people can easy understand, is another home-grown innovation we are proud of,” said Maria Elena Filio Borromeo, UNAIDS Country Director for Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Resources

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Sex workers adapting to COVID-19

21 April 2020

21 April 2020 21 April 2020Although difficult for everyone, the COVID-19 pandemic has had severe impacts on key populations, many of whom are experiencing economic hardship and anxiety about their health and safety.

Rito Hermawan (also known as Wawan), the Advocacy Coordinator of the Network of Sex Workers of Indonesia (OPSI), explained that the places that sex workers work in Indonesia have been closed down. Since, for their own safety, sex workers are avoiding working on the streets, many have been left without an income, unable to make ends meet.

It’s been about a month since Indonesia enacted a set of preventive measures against COVID-19. With the uncertainty of when life may return to normal, OPSI is supporting the urgent needs of the sex worker community.

Many sex workers are increasingly needing mental health support to combat the stress and anxiety they are currently experiencing. In a rapid survey conducted by the Indonesian Positive Network to review the needs of people living with HIV and key populations, more than 800 out of 1000 people surveyed expressed a need to access mental health and psychosocial support.

In order to address this, OPSI uses social media to provide virtual mental health support. “Through our social media, we are able to reach sex workers and empower them with information, motivation and support. They need to know that they are not alone, even though we may not be physically close,” said Mr Wawan.

A video teaching meditation and breathing techniques was recently launched to help sex workers cope with stress and to improve their general well-being. OPSI is also highlighting innovative work, such as making masks for sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. For those who need one-on-one support, OPSI has also established a counselling hotline.

In addition to supporting the sex worker community in Indonesia, OPSI is also exploring ways for outreach efforts to be continued despite the current conditions. The essential work of outreach workers should not come to an abrupt halt because of COVID-19, but it will need to move to a virtual form.

With technical assistance from the United Nations Population Fund Indonesia, OPSI developed a module on virtual outreach. The module outlines how outreach workers can adapt their work online, such as by using WhatsApp. The outreach workers are provided with lists of HIV counselling and testing services that are still open in 88 districts in Indonesia, which they can use to refer sex workers.

Sex workers, like others, are facing incredible hardships during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether it be struggles with their mental health, difficulty in continuing their work and loss of income. The role of networks and organizations of sex workers like OPSI is incredibly important in ensuring that the needs of sex workers are supported at this vital time.

Resources

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

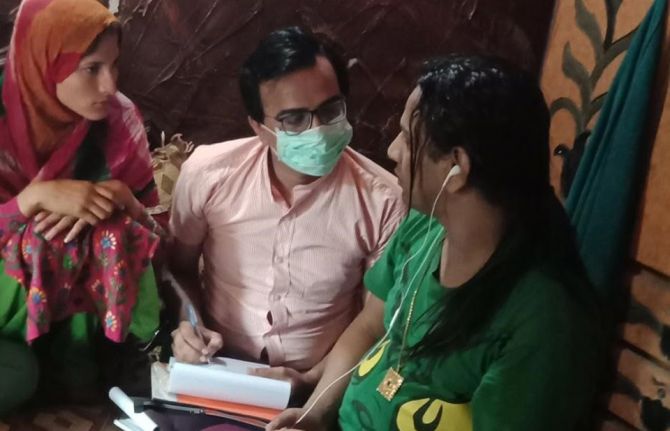

Keeping HIV treatment available in Pakistan during COVID-19

15 April 2020

15 April 2020 15 April 2020Sitting near her broken window, Ashee Malik (not her real name), a transgender woman who lives in Punjab Province, Pakistan, is counting her earnings, realizing that her income has fallen sharply. Her only source of money is dancing, begging and entertaining her clients, but since the lockdown imposed on 20 March to stop COVID-19, she hasn’t been able to leave her home. Her bright clothes are in her wardrobe, as is her makeup kit, laying unused for weeks. “We are concerned about our well-being, as we do not have enough resources to support ourselves and our families,” she said.

Ms Malik’s story is similar to that of most transgender people living in Pakistan, who face stigma, discrimination and social isolation. Access to health services, education and employment is one of the many challenges that transgender people face in the country, despite the passing of the Transgender Persons Protection of Rights Act 2018. And COVID-19 and the associated lockdown are making matters worse. As of 15 April, there were more than 5900 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Pakistan and 107 deaths.

Owing to the restrictions on the movement of people, there is a real risk of a disruption to critical services for people living with HIV, which disproportionality affects transgender people in Pakistan.

The Khawaja Sira Society (KSS), which works with transgender people, has stepped in to provide support, working with the most marginalized and promoting knowledge about how to prevent HIV and COVID-19.

“The transgender community is even more vulnerable due to the prejudice and stigma and discrimination against them. We need to develop a COVID-19 prevention model by keeping in mind the dynamics and issues of the community in this pandemic,” said Mahnoor Aka Moon Ali, the Director of Programmes for KSS.

During discussions that KSS had with 150 transgender people, of whom approximately 30% are living with HIV, several issues were repeatedly raised, including the lack of income and the small size of Dheras, community homes for transgender people, in which four or five transgender people live together, making social distancing difficult. Since most of the transgender people contacted are illiterate, public health campaigns on how to prevent infection by the coronavirus are not getting through. Fear of the disease is high, which is impacting on mental health. The Government of Pakistan has announced that food aid will be made available, but transgender people face challenges in accessing the scheme, which is dependent on verification based on the national identification card, something that most transgender people in the country simply don’t have.

Social media is increasingly being used during the lockdown and together with UNAIDS Pakistan, KSS is disseminating information on hygiene, preventive measures and social distancing on social media and is engaging with the community on COVID-19. KSS, together with provincial government authorities, is also working to ensure that people living with HIV can get multimonth refills of antiretroviral therapy delivered to their home.

“We as transgender people living with HIV feel we are at risk by visiting government-run antiretroviral therapy centres. We need antiretroviral therapy to be delivered to us,” said Guddi Khan, a transgender woman who is living with HIV.

Since an uninterrupted supply of antiretroviral therapy is essential for people living with HIV, the Pakistan Common Management Unit for AIDS, TB and Malaria, in collaboration with UNAIDS and other partners, has established virtual platforms and helplines in order to ensure that coordination is continued. An emergency stock of antiretroviral therapy has been made available for people living with HIV for the next two months and a buffer stock is being made available through the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in order to avoid interruptions in the event that imports of medicines are disrupted.

“We are working closely with the Association of People Living with HIV, federal and provincial governments and the UNAIDS family to monitor the situation and quickly help address barriers in accessing life-saving HIV services in these extremely challenging times of the COVID-19 crisis,” said Maria Elena Borromeo, the UNAIDS Country Director for Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Resources

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Community networks extend arms to connect people to medicine in Viet Nam

17 April 2020

17 April 2020 17 April 2020When the Vietnamese Government introduced social distancing mid-March 2020 to respond to COVID-19, Binh Nam (not his real name), already on distance learning from his college since February, lost his part-time job at a small company. He decided to leave Ho Chi Minh City, which had a cluster of confirmed COVID-19 cases, to settle back in his home town, about 300 kilometres away.

“Going home seemed like the best option for me at the time,” Mr Nam said.

He arrived at his parents’ home just before buses shuttling people back and forth across the provinces stopped. With stricter lockdown measures taking effect in early April, he realized he was in a bind. He would run out of HIV treatment.

“I considered going to a local HIV clinic, but feared my HIV status would be disclosed,” he said. “I also could not buy antiretroviral medicine at private clinics because that would clear out my savings.”

And he definitely did not want to ask his parents, because they didn’t know he was living with HIV.

“I felt desperate,” he said. As a last resort, Mr Nam texted a man who runs a social media channel on HIV information, education and counselling that he follows.

Upon learning of Mr Nam’s situation, Nguyen Anh Phong, a representative of the Viet Nam Network of People Living with HIV (VNP+) in the south of Viet Nam and co-founder of the Lending a Helping Hand Fund, mobilized some funds to get him an antiretroviral therapy refill.

“This was among the first calls for help that made us notice more and more people were stuck in their home province with a limited amount of antiretroviral medicine,” Mr Phong said.

He and his VNP+ peers decided to form a group on one of the most popular social media chatting platforms in Viet Nam to find ways to connect people and help them collect medicine at clinics other than their own. More than 150 community members joined the group across the country.

Community feedback filtered back to the Viet Nam Authority for HIV/AIDS Control (VAAC) at the right time as it was drawing up emergency contingency plans. It was dealing with a hospital closed because of a temporary COVID-19 quarantine in Hanoi, so people couldn’t access HIV services or treatment. And with so many people stranded in the provinces, something had to be done.

VAAC issued new guidelines on HIV care and treatment during the pandemic developed with technical support from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the United Nations.

“We invited the Viet Nam Network of People Living with HIV to join our technical discussions and to give us feedback because they know the challenges faced by people living with HIV,” said Phan Thi Thu Huong, VAAC Deputy Director in charge of HIV care and treatment.

The guidelines allow for multimonth antiretroviral therapy refills for all people on HIV treatment and for the provision of pre-exposure prophylaxis and tuberculosis medicines.

Provinces have been assigned focal points and hotline numbers for people who experience unusual symptoms.

More importantly, the standard referral requirements were eased in order to allow clients temporary access to alternative HIV clinics for antiretroviral therapy refills. VAAC also proactively resolved procurement challenges in order to avoid stock-outs, so Mr Nam and others could access HIV clinics of their choice for refills.

Viet Nam’s HIV epidemic is concentrated mostly among gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender women, people who inject drugs and female sex workers and their intimate partners, with a rising HIV prevalence among gay men and other men who have sex with men .

“I believe that by joining hands, we can help all people get their refills so that no one misses their treatment because of COVID-19,” said Mr Phong.

Working hand in hand and getting results is what communities do best, according to Marie-Odile Emond, the UNAIDS Country Director for Viet Nam. “These networks are pillars of peer support and resilience and now more than ever they’re like an extended arm of the public health sector,” she said.

Resources

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Ensuring that people living with HIV in the Philippines have access to treatment during COVID-19

08 April 2020

08 April 2020 08 April 2020The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown imposed by the Government of the Philippines to curb the spread of the disease are impacting the lives of people living with HIV across the country, creating a serious challenge to accessing life-saving antiretroviral therapy. To help address those challenges, civil society organizations have come together to support people living with HIV to access treatment.

Through a coordinated community-led mechanism, Network Plus Philippines, Pinoy Plus Advocacy Pilipinas, the Red Whistle and TLF Share Collective, are working together in the implementation of a new guideline issued by the Department of Health. The new guideline directs local authorities to ensure that people living with HIV can collect their medicine at the nearest HIV clinic and encourages the use of courier services for the pick-up and home delivery of antiretroviral therapy in order to avoid the risk of increased exposure to COVID-19.

“For many people living with HIV, accessing antiretroviral therapy from the nearest treatment hub is a welcome development. However, the nearest facility may not be within walking distance, and public transportation has been restricted. To be able to reach the HIV clinic, some need to pass through checkpoints, where they fear disclosure of their HIV status, as a few have already reportedly experienced,” said Richard Bragado, Adviser of Pinoy Plus Advocacy Pilipinas, an organization of people living with HIV, and the Administrator of Network Plus Philippines, the national network of organizations of people living with HIV.

The Red Whistle, a platform that raises awareness about HIV, has mobilized a pool of 40 volunteers to collect antiretroviral therapy refills from treatment hubs and deliver them to people across the country. TLF Share Collective, a civil society organization working on the sexual health, human rights and empowerment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people, tapped the volunteers of its partner community-based organizations to deliver antiretroviral therapy.

“People living with HIV are displaced by the pandemic. Some lost their source of income and had to return to their original residence after losing their jobs. Ensuring uninterrupted treatment is not to be compromised. This is an integral part of our work on human rights,” said Anastacio Marasigan, Executive Director of TLF Share Collective.

Home delivery is made possible through a joint effort of civil society organizations and health facilities. “We ask treatment hubs to issue a letter of authorization to show to the checkpoint authorities that the driver is delivering essential medications. We are also working with local authorities to avoid unintended disclosures of confidential information of our clients at the checkpoints,” said Benedict Bernabe, Executive Director of the Red Whistle.

To identify the nearest treatment hubs, lists of antiretroviral therapy clinics have been disseminated through different channels, with the Red Whistle partnering with MapBeks, an online LGBTI mapping community, to create the Oplan #ARVayanihan, a map that includes all treatment hubs and primary HIV care facilities.

People living with HIV can share and ask for information through different platforms. Among them is the PLHIV Response Center, established by Pinoy Plus Advocacy Pilipinas to link callers with services. The hotline disseminates information about treatment hubs available and gives advice on how to access antiretroviral therapy.

TLF Share Collective has developed a tool to monitor the delivery of antiretroviral therapy by the community volunteers. The organization also developed frequently asked questions cards and consolidated existing hotline numbers.

“UNAIDS has regularly coordinated with civil society organization since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, providing technical guidance and ensuring synergy with the efforts of the government,” said Louie Ocampo, UNAIDS Country Director for the Philippines.

The United Nations Development Programme and UNAIDS have developed a rapid survey to assess the different issues affecting people living with HIV in the Philippines. In addition to access-related issues, the results of the survey show the urgent need to protect human rights and facilitate access to mental health and social protection services. The findings have been shared with the government in order to ensure that actions are based on the constantly evolving situation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Supporting transgender people during the COVID-19 pandemic

06 April 2020

06 April 2020 06 April 2020The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted people’s lives around the world, including those of many marginalized people, who suddenly face additional burdens and vulnerabilities.

Many areas in Indonesia, which as of 6 April had 2491 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 209 deaths, have put in place measures, such as physical distancing, to curb the spread of COVID-19. While effective in responding to the disease, many people have been impacted by the effects of physical distancing on the economy.

Out of 1000 people living with HIV and members of key populations surveyed by the Indonesian Positive Network, more than 50% are experiencing severe impacts on their livelihoods, including many transgender women. Sanggar Swara, a civil society organization of young transgender women in Jakarta, conducted a rapid assessment that found that more than 640 transgender people in greater Jakarta have lost their jobs, leaving them unable to support themselves. “On several occasions when the distribution of basic food staples took place, many of them could not access it as they do not have their identity cards on hand or simply due to their gender identity,” said Kanzha Vinaa, the head of Sanggar Swara.

Seeing the critical need for support, the Crisis Response Mechanism (CRM) Coalition, fronted by the civil society organizations LBH Masyarakat, Arus Pelangi, Sanggar Swara and GWL Ina, with support from UNAIDS Indonesia, decided to raise funds for the transgender community. “Since 28 March, we spread the information about the fundraising to communities and partners. Our plan was to collect the funds and distribute them to transgender women in need, with support from focal points in the areas,” said Kanzha Vinaa.

In less than a week, the CRM Coalition had collected more than IDR 67 000 000—around US$ 4100—and distributed food and hygiene packages to more than 530 transgender women in greater Jakarta. The packages cover the basic needs for one week. Ryan Kobarri, the head of Arus Pelangi, said, “Initially we only expected our close networks to respond to this call for donations. We were elated to see that the support and enthusiasm was much more than we expected. Not just from local networks, but even international networks gave their support. Someone even donated 100 kg of rice!”

Although there is uncertainty over how long the current COVID-19 situation will last, it is very likely that the need will persist in the coming weeks and months. The CRM Coalition continues to welcome donations from all around the world in order to keep the community afloat during these difficult times.

Since its establishment in 2018, the CRM Coalition has worked to coordinate and mobilize resources to respond to the persecution and discrimination faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people in Indonesia, one of the most vulnerable communities in the country.

Donations to help keep this vital work going can be made by PayPal at paypal.me/kanzha or through Ryan Kobarri at ryan@aruspelangi.or.id.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“You’re welcome!”

30 March 2020

30 March 2020 30 March 2020“You’re welcome!”

Sunny Dawson (not his real name) jumped with joy when he received his medicine from Bai Hua. “You're an angel sent by God,” he said to him.

Mr Dawson is an English teacher at a school in a small town in northern China. In January, he went on a vacation to his home country in south-east Asia, but his journey back to China turned out not to be as easy as his journey out. The coronavirus outbreak that started in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, and quickly swept across China has posed big challenges to everybody’s life. But because he is living with HIV, the challenges for him were probably greater.

Rushing back to China

News about the outbreak in China hit the headlines in Mr Dawson’s home country during his vacation. “All my family objected to me going back to China,” he said. But he loves China and wanted to go back. “I needed to rush back before flights were stopped,” he said. His family conceded, his father giving him a big bag of face masks before his departure.

He thought he was fully prepared, but when his flight landed, he could feel that things were different. All the passengers had to have their temperature checked, one by one. Mr Dawson was wearing heavy clothes that day and was sweating a little—his temperature read 37.6 degrees Celsius. He and some other passengers were sent to a nearby hospital for further tests.

He tested negative for COVID-19, but soon after learned from the head teacher of his school that the small town he works in has been put under lockdown—he couldn’t go back to where he worked.

Since he is living with HIV, he needs to take antiretroviral medicine every day. He had only taken a one-week supply with him on his vacation, though, and it was running out.

BaiHuaLin alliance of people living with HIV comes in to help

Mr Dawson remembered Bai Hua , the founder of the BaiHuaLin alliance of people living with HIV, a community-based organization dedicated to supporting people living with HIV, including help with refills of medicine. BaiHuaLin was the organization that reached out to him when he was scared and lonely after being diagnosed with HIV a year before.

The coronavirus outbreak left many people like Mr Dawson at risk of running out of their medicine because they were stranded away from their usual HIV service provider. The BaiHuaLin alliance helps people in need of HIV medicine to get their refills by using an extensive network of volunteers that covers the whole country and extends globally. “Too many people need refills these days. We are terribly busy,” Bai Hua said.

When he received Mr Dawson’s call for help, he told him to come to his office immediately to pick up the seven-day refill he had requested. However, only a few days later he had to return for more because his stay in Beijing had been extended indefinitely. “My colleagues told me not to go back in the near future because the shops are closed under the lockdown,” he said. This time, Bai Hua gave him a month’s refill.

A strong partnership

The UNAIDS Country Office in China also felt the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on people living with HIV. “We received messages on social media from people living with HIV, expressing their frustration and desolation and seeking help,” a UNAIDS staffer said.

Because of HIV-related stigma, when faced with the risk of the disruption of medicines, people living with HIV often choose to keep their anxiety to themselves, afraid to reveal their status. “Some people say they would rather die than disclose their HIV status,” Bai Hua said. “One person sneaked out of his village and walked 30 kilometres to get the medicine.”

The UNAIDS Country Office in China has been working to ensure that the rights of people living with HIV are fully protected. In addition to giving out information, UNAIDS also actively works with the government and community-based organizations in China in order to ensure that people living with HIV get medicine refills.

Special pick-ups and mail deliveries of HIV medicines arranged by UNAIDS have reached more than 6000 people living with HIV in Wuhan.

Best yet to come

Mr Dawson finally got back home to the small town in northern China after staying in Beijing for more than two weeks. Still under quarantine, he misses an old man in the park near his apartment. “He was my calligraphy teacher. He always goes to the park, writing Chinese calligraphy on the ground,” he said. He gave Mr Dawson a piece of calligraphy, beautifully framed, that is now hung on the wall of his sitting room.

“I look forward to the day when the virus is gone,” he said, “So I can visit my friends and learn calligraphy in the park.”

Resources

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Strengthening services for violence against women and HIV in Indonesia

27 March 2020

27 March 2020 27 March 2020Nining Ivana, the local coordinator of the Indonesia Positive Women Network (IPPI), Jakarta, was shocked when she received a voice message from one of the network’s new members.

In the message, Mutiara Ayu (not her real name) said that she had been beaten by her husband and abused by her husband’s family when they discovered that both her and her son were living with HIV. Research by IPPI in 2011 found that, like Ms Ayu, more than 28% of its members across Indonesia had experienced violence from their partners and family members because of their HIV status. It is known that women who are victims of sexual abuse are also at a higher risk of contracting HIV.

To address the linkages between HIV and violence against women, IPPI is holding a series of workshops to better integrate services for HIV care, support and treatment and against violence against women across eight cities in Indonesia. IPPI members who are survivors of violence, local HIV service workers from public health clinics and managers of women’s shelters have been attending the workshops, at which the results of the IPPI’s research are disseminated, needs are discussed, experiences are shared and a local action plan to better integrate both services is decided upon.

“I heard stories from HIV service providers at public health clinics. They couldn’t understand how a woman living with HIV had such a low CD4 level despite routinely visiting the clinic. Apparently, her husband banned her from taking her antiretroviral medicine. They know that these women are more likely to be victims of violence, but they do not know where to refer them to, since there is no standard operating procedure beyond their health care,” said Chintya Novemi, the person in charge of integrating services for HIV and violence against women at IPPI.

In addition to HIV care, support and treatment services, women living with HIV who are victims of violence may need counselling for trauma and legal aid should they decide to pursue litigation. Through its HIV & Violence against Women Services Integration Project, IPPI aims to bridge this gap. When there is not a formal relationship or mechanism, or it is not clear, informal referral mechanisms made by local stakeholders could save a woman’s life.

“After meeting with workers from services for HIV and violence against women at the workshop, it became clearer to me where I should refer IPPI members who encountered violence and how we should handle their cases,” said Ms Ivana, who joined the workshop in Jakarta.

Upon finishing the series of workshops, IPPI hopes to disseminate the results to national stakeholders, including the National Commission on the Elimination of Violence against Women, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Law and Human Rights and others. The ultimate goals are to gather evidence regarding these interlinked issues and advocate for a national standardized mechanism to protect women living with HIV from all forms of gender-based violence.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Community members are driving the AIDS response in northern Myanmar

26 March 2020

26 March 2020 26 March 2020Saung Moon was 15 years old when he first injected drugs. “I went out with some people who were using heroin and they persuaded me to try,” he said, puffing on a traditional Myanmar cigarette while squatting around a small fire with his friends.

Mr Moon, now 20 years old, lives in Putao, a remote area at the northern tip of Myanmar. Small rural communities are scattered around the mountainous region, part of the foothills of the Himalayas. But this lush and pristine environment is home to a severe drug epidemic fuelled by the availability of cheap heroin in the region. Widespread injecting drug use is resulting in high rates of HIV and hepatitis B and C infection.

Mr Moon and his friends were huddled around the fire at one of the two Medical Action Myanmar (MAM) facilities in the Putao district. The clinic is a satellite centre of the national AIDS programme and provides services—including needle–syringe exchange, HIV counselling and testing, HIV treatment and care, primary health care, testing and treatment of sexually transmitted infections and family planning—to people who inject drugs. The clinic also refers heroin users to the local hospital for opioid substitution therapy, since only government facilities are currently allowed to distribute methadone in Myanmar.

Mr Moon and his friends feel at ease at the clinic. Some are there to return their used needles and syringes and get clean ones, others to test for HIV or access their HIV treatment. Whatever the reason, health-care workers at the clinic take the opportunity to talk to them and train some of them as peer educators.

“If peer pressure is one of the main causes for heroin use initiation, the same principle applies when it comes to advising about the dangers of injecting drugs and how to prevent HIV transmission,” said MAM’s Medical Director, Cho Myat Nwe.

Raising awareness among people who use drugs is the first step in responding to the drug-related HIV epidemic—there isn’t a more effective way than sharing information and life skills among peers. “At school, we only received a brief talk about drugs, but nothing on HIV,” said one of Mr Moon’s friends. “With the information and training we have received at the clinic we can talk to our friends and provide them with important information to prevent infection.”

Engaging people who use drugs is only half of the challenge. The other half is reducing the stigma and discrimination they encounter in their daily lives.

According to Mrs Cho, people who use drugs are not very popular in their communities. The villagers do not understand why nongovernmental organizations focus their activities on people who use drugs and not on the general population. MAM is therefore working in the communities, providing general health care and discussing drug use and HIV, explaining why services for people who use drugs will have a positive effect on the community as a whole.

Services difficult to access

For most people who use drugs in Putao, getting to the clinic is a problem. The remoteness of the villages—some of them are as far as seven days away from the nearest health facility by foot—the poor infrastructure and the lack of public transport makes accessing services very difficult, especially during the rainy season. This leads to relatively high levels of people on long-term treatment stopping their treatment, including HIV treatment and opioid substitution therapy. “The problem is always transportation to come to the clinic or to the health centre to access methadone,” said another of Mr Moon’s friends. “We don’t have the money or the means of transportation to go to the hospital every day.”

MAM has mobile clinic teams visiting other villages in the district. The clinics stay open at night to make access easier, conduct outreach sessions and provide information on harm reduction and HIV prevention where people who use drugs gather. That’s how Mr Moon and his friends got to know about the clinic and the health options available to them. However, the reach of the mobile clinic is limited.

Community health volunteers are making a difference

Community health volunteers, who provide a wide range of health services in the villages, have made a real difference to the ability of people to access services.

The volunteers were originally trained by MAM staff to test and treat malaria. People with fever would visit them. They would then perform a simple test and if positive for malaria they would provide treatment immediately. According to the health authorities, the volunteers were part of a successful effort that led to a decline in the malaria rate among those reporting fevers in Putao from 4.2% in 2015 to 0% in 2019.

Now trained twice a year, their services have grown beyond malaria testing and treatment to include counselling for HIV, needle–syringe exchange, tuberculosis referrals, sexual and reproductive health services and the referral of severely ill patients to government hospitals.

Despite their limitations, community health volunteers are bringing health services and information much closer to people and are reaching out to a population that would be otherwise very hard to reach. Their work is greatly contributing to the decentralization of services and is helping to unblock an overstretched health system.

While still insufficient to cover the needs of the community, the response to HIV in Putao links community health volunteers, a nongovernmental organization clinic and a township hospital providing antiretroviral therapy and opioid substitution therapy. As such, it is an example of a strategy that can be further expanded for wider coverage in nearby localities.

The predominantly rural nature of injecting drug use in the country poses challenges for how to effectively deliver harm reduction services. While Myanmar has unique examples of how to adapt programmes to local contexts, there is an urgent need to evaluate the public health outcomes and impact of such innovative and adapted responses in the coming months as the country gears up to further intensification of its AIDS response with support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief and Access to Health.

Resources

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025