PLHIV

Feature Story

Urgently needed HIV services are supporting Ukrainian refugees in the Republic of Moldova

07 April 2022

07 April 2022 07 April 2022Many of the Ukrainian refugees seeking sanctuary in the Republic of Moldova are from Odesa or the surrounding region, which is one of the regions of Ukraine most affected by HIV.

Iryna Kvitko (not her real name) fled with her entire family, including her daughter-in-law and young grandson, to the Republic of Moldova. She said that an air-raid siren would sound several times a day, terrifying her grandson. “We thought about whether we should go or not, but it was scary to sit all night in our home—me, my husband, son, daughter-in-law and grandson—and try to explain to the child what the explosions and sounds of shooting were. Plus, to be honest, I was very afraid of the situation regarding my antiretroviral therapy—I was running out of it and it was not clear what would happen next.”

Ms Kvitko has been living with HIV for more than 15 years but keeps her diagnosis a secret. “I work, we live decently. I have a family, children, relatives, friends, colleagues. God forbid that someone would find out—it would all go to dust,” she said.

She described her difficult journey to the Republic of Moldova—there was widespread panic and at the border checkpoints the queues of traffic reached up to 80 kilometres. “Many people just got out of their cars and walked. Our main goal was to take our children and grandson out of Ukraine,” she said.

“My doctor in Odesa gave me information on where people can go to get help with antiretroviral therapy. I called them and after they took my contact number they immediately called me back and explained where to go and what to do and said that they would help me and give me the medicines I need.”

On the very first day of the war, Ihor Plamos (not his real name), together with his wife and child, drove to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa. There were a lot of people at the border, he recalled. “As soon as we got to our destination, I started to drive back to the border, to give a lift to people who had travelled on their own, who had walked seven or eight kilometres.” He took them to an aid distribution centre, from where they travelled on to Georgia or Germany.

“When we arrived, we didn’t know what to do. So, I called my doctor in Ukraine, and she told me where to go,” he said.

The clinic that his doctor referred him to tested his viral load free of charge, and the doctor prescribed antiretroviral therapy for him. He does not want anyone to know that he is living with HIV, noting that the level of stigma around the virus remains very high. “Therefore, I was worried at the beginning about what would happen to my treatment,” he said.

Hanna Brovko (not her real name) travelled to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa with her 11-year-old son, leaving behind her sewing business, clients and friends. She has been living with HIV for more than 12 years, but she does not tell people about her diagnosis. “I don’t need pity, and I don’t want things to be said about me behind my back.”

She received all the necessary medicines upon her arrival in the country but decided to move on to Germany. Berliner Aids-Hilfe helped her to arrange her flight from Chisinau to Berlin, set up her in a family’s house and arranged medical insurance, which is necessary for her to obtain her HIV treatment.

Elena Golovko, an infectious diseases doctor at the Hospital of Dermatology and Infectious Diseases in Chisinau, emphasized that people who come from Ukraine receive all HIV services in the same way that Moldovan people living with HIV do. “Today, we have a person living with HIV hospitalized, there are several HIV-positive women, there are those who have already given birth here and who received syrup to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. There is also a person receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis. We issue a 30-day supply of antiretroviral therapy to refugees. If people stay longer in the country, they can come and receive a refill. We don’t have any problems with ensuring the same level of HIV services,” she said.

However, she added that some people did not know their latest test results or could not remember the name of the medicines they take. “It was important for us to establish communication with colleagues in Ukraine, especially fast communication when a person is directly in the clinic.”

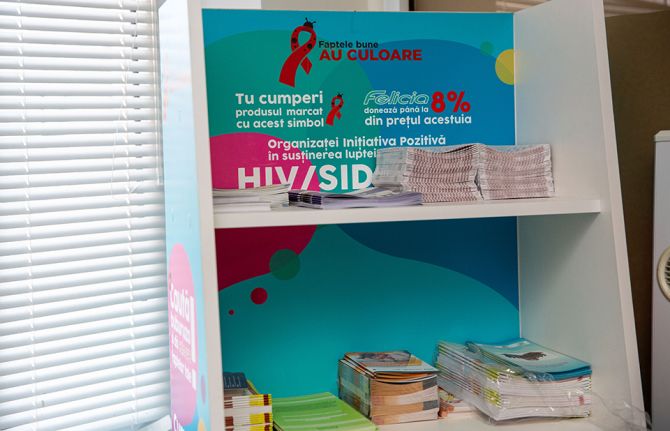

Alina Cojocari, the coordinator of assistance for people living with HIV at the Positive Initiative nongovernmental organization highlighted that it is fully involved in service delivery for refugees in need of HIV services. “We are referring people to health services, supporting them with accommodation in the country and offering them psychosocial and legal support,” she said. “For those travelling from the Republic of Moldova to other countries, we ensure they are linked to HIV services in the next country,” she added.

“This level of HIV services for refugees living with HIV in the Republic of Moldova became possible as these services in the country have long been built around people’s needs,” said Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Country Manager for the Republic of Moldova. “This approach is now also being used for refugees. During humanitarian crises, such as the war in Ukraine, everyone is vulnerable and people fear for their loved ones. For people living with HIV, there is also the fear of not receiving timely, life-saving HIV treatment, and in many cases the fear of the disclosure of their status. That is why it is so important to create sustainable, agile, equitable health and social protection systems with people at the centre, which can protect people during a crisis.

Related

Feature Story

Encouraging income generation and social entrepreneurship by people living with HIV in Brazil

29 March 2022

29 March 2022 29 March 2022In the city of Recife, capital of the state of Pernambuco, in the Northeast Region of Brazil, a specially adapted bicycle carries products made by people living with HIV to be sold directly to consumers. It is called the Diversibike, one of the strategies for income generation implemented in the context of the Solidarity Kitchen, a project developed by the Posithive Prevention Working Group (GTP+) nongovernmental organization, one of the three Brazilian organizations that have benefited from resources from the UNAIDS Solidarity Fund, whose objective is to support entrepreneurial activities led by people living with HIV and key populations.

GTP+ was created in 2000 and was the first nongovernmental organization in the Northeast Region of Brazil to be led exclusively by people living with HIV. Among the projects developed by the organization, in addition to the Solidarity Kitchen, are the Espaço Posithivo, which welcomes people living with HIV who seek support, and Mercadores de Ilusões, which works to support sex workers to strengthen their self-esteem and claim their rights to citizenship.

The Solidarity Kitchen emerged in 2005, initially to produce meals for people living with HIV who sought support from GTP+. In 2019, a new element, the Confectionery School, was added to provide sex workers, ex-prisoners and other vulnerable people living with HIV with a way to generate income through cooking. With the resources received from the Solidarity Fund, GTP+ was able to boost initiatives to commercialize the products developed in the Solidarity Kitchen and train the participants in different aspects of entrepreneurship.

“The project has contributed to transforming the lives of people living with HIV in vulnerable situations. Through the project, they found an opportunity to generate income through entrepreneurial activities and developed their skills in gastronomy, learning recipes and techniques to improve their products,” said Wladimir Reis, the General Coordinator of GTP+.

Sérgio Pereira, one of the founders of GTP+ and the Coordinator of the Solidarity Kitchen, agreed, adding, “When the job market knows that we live with HIV, it doesn’t accept us. The Solidarity Kitchen brings to the participants the possibility of sustainability and opens doors for them to be able to enter the job market.”

Karen Silva, one of the beneficiaries of the Confectionery School of the Solidarity Kitchen, said, “I was welcomed at GTP+ with a lot of attention and care. First, I participated in the Posithive Space, then little by little I started helping in the kitchen and here I am. Participating in the Solidarity Kitchen changed my life and my self-esteem as well.” In total, 20 people have directly benefited from the Solidarity Kitchen, with the support of the Solidarity Fund.

As the objective of the project was on finding and promoting the best conditions for marketing products made in the Solidarity Kitchen, the team responsible for the project held weekly planning, organization and production meetings. They also conducted market research to identify the tastes and interests of potential customers, which was especially important in identifying Diversibike’s potential.

According to Mr Reis, an important part of the process of capacity- and knowledge-building of the group of project participants were the virtual trainings in gastronomy and administration offered through a partnership with the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco. Two scholarship-holders from the university supported the group in the meetings and by producing support materials.

One point to which Mr Reis draws attention is the fact that the project was born in a time of extreme social inequality. “For this reason, it is essential that we implement more initiatives like this, with support from the Solidarity Fund, so that other people in vulnerable situations can have the same development opportunities. With the project, we were able to observe the impact of generating financial resources for the participants, in addition to strengthening their knowledge to implement their projects and ensure their sustainability during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“The Solidarity Fund’s support for GTP+ highlights the importance of guaranteeing income generation by organizations led by vulnerable key populations. It is a strategic action, which generates social protection for those people, allowing them access to basic resources to take care of their health and to access HIV prevention and treatment services,” said Claudia Velasquez, the UNAIDS Country Director for Brazil.

Region/country

Feature Story

“With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises”

23 March 2022

23 March 2022 23 March 2022Yana Panfilova is Ukrainian and was born with HIV. When she was 16 years old, she created Teenergizer, a civil society organization to support adolescents and young people living with HIV in Ukraine. Since 2016, Teenergizer has been working internationally, promoting the rights of teenagers and young people in Ukraine and in seven cities in five countries across eastern Europe and central Asia. In 2019, the organization began providing peer counseling and psychological support to adolescents, and has trained more than 120 online consultants–psychologists to support young people across the region. In June 2021, she spoke at the opening of the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on AIDS. When the war in Ukraine started, she left Kyiv, Ukraine, with her family and made her way to Berlin, Germany, from where she is continuing her work to support young people living with HIV in Ukraine.

Why and how did you leave Kyiv?

Within days of the start of the Russian invasion I understood that we needed to make a life-changing decision—people with machine guns were patrolling the streets. I had to convince my mother that we needed to leave, because she was reluctant to go. We packed up our lives in less than an hour, drove to Kyiv railway station, left our car there and boarded the first train that we could find. There were so many people, mothers, children, and fathers and brothers seeing off their families, and many people were panicking. We had to stand on the train for 12 hours, with our suitcases and our cat. When our grandmother caught up with us at our first stop, we travelled together from Ukraine, along with her dog, crossed the border to Poland and went on to Berlin. The entire trip took seven days. It was the longest and most challenging trip of my life—I didn’t want to leave my beautiful Kyiv not knowing where we would end up. Now we are here in Berlin, refugees, safe and secure, but still in disbelief about what we have been through and distraught about what is happening to the people of Ukraine. But at least we are safe and together—my mother, my grandmother and her dog, and me and my cat. I was lucky that I brought enough antiretroviral therapy to last about two months.

Are you settled in Berlin?

I’m still in limbo, like millions of other Ukrainian women and children who have made this journey. But everyone we have met at every step of this journey has been so kind and welcoming. We are now clarifying the legal aspects of how to stay here in Berlin for the next few weeks and how we can access local medical and social services. Even how we can rent an apartment is still not yet clear. We made an appointment online with the municipality of Berlin to clarify the details with them. They are working to provide me with medical insurance so I can get access to medical care and uninterrupted access to HIV treatment.

I am also in contact with Berliner Aids-Hilfe, one of the oldest nongovernmental HIV organizations in Europe; after the war in the former Yugoslavia, they have a lot of experience in working with migrants living with HIV. They have been amazing, ready to help with access to antiretroviral therapy as well as the other needs that Ukrainians living with HIV will have here in Berlin.

So, you're more or less safe now. How are the other young people from Teenergizer doing?

Most of our teenagers living with HIV have already left Ukraine and now they are in Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, Poland and other countries. We are in contact with most of them every day. Some of our activists chose to stay with their parents in Kyiv and other cities that are under attack. We are now clarifying the latest information and trying to monitor where everyone is, and if they are safe. But this is not a quick or easy process. Everyone is now trying just to survive and stay in contact. Our staff, peer educators and clients are now scattered across different countries, each with different laws, treatment regimens and access to the Internet. Those still in Kyiv are connected with our partners, who are still providing access to antiretroviral therapy and emergency humanitarian assistance. Most of our consultants–psychologists are still providing online assistance to those in most in need.

What are the issues you are dealing with to stay in Berlin?

The people here in Berlin and all the Germans we have met since we arrived have been incredibly kind and welcoming. We are very grateful. I know all cities across Europe are struggling to support millions of Ukrainians, but I don’t think we could have found a safer and more tolerant place to stay than Berlin.

Of course, our most urgent questions are of a legal nature related to temporary status here and, second, questions about access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy. Third is housing. I never thought housing would be so important or so nerve-wracking. Local volunteers are helping around the clock, and millions of Europeans have opened up their homes. But for the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians still living in warehouses, shelters and other temporary accommodation, the lack of a place you can call a temporary home can crush your spirit.

What do you think is most important to keep doing now?

No matter what happens with the war, we have to continue supporting each other in the Teenergizer family. In Ukraine, we spent years fighting so that young people living with HIV could have our health and rights protected. And now it feels like so many of our hard-won gains have disappeared overnight. In the middle of this crisis, we have to keep standing up for our rights and focus on the urgent needs facing the most vulnerable members of our Teenergizer network. I am so lucky to be alive and here in the safety of Germany. But many of our friends are still in Kyiv and in other cities across Ukraine, fighting for their lives and our country. Some of them have no way out and others don’t want to leave their homes and their families. Now, more than ever, they need our support and reassurance that we will continue to do everything we can to support them when they need it most.

First, we need to help them to navigate this new crisis and continue life-saving services—HIV treatment for those who urgently need it, and prevention and testing services. Second, during this crisis, we must continue to provide young people with mental health services, especially peer counselling. In our region, HIV is more of a social problem than a health problem. Today, young Ukrainians living with HIV are facing the triple crises of their health, their safety and acute stress and depression caused by the war. Psychologists call it PTSD. This trauma is continuing for an entire generation of Ukrainians. Young people who need professional psychological support will start using drugs and some of them will contract HIV, but they will be too scared or ashamed to ask for help in the current crisis. The same applies to adolescent girls and women who cannot exercise their reproductive and sexual rights, or young people who do not use a condom during sex, or millions of Ukrainian women who are at risk of exploitation when they are alone in Europe, away from their families and friends. Today, thousands of adolescents still in Ukraine who are living with HIV are afraid to reveal their status. Many still do not know how to protect themselves from HIV and from the violence of war. Millions of Ukrainian youth are left alone to cope with their anxieties and fears, and an entire generation will be dealing with post-traumatic disorders—this needs urgent attention. I am convinced that if we provide even basic counselling and support now, young people facing multiple crises will be better able to cope with their problems for years to come.

And also no matter what, we have to push politicians to listen to young people and allow them to influence the decision-making process about their own health and future. The voices of young people, especially young women, should be heard to stop the war and rebuild Ukraine.

How do you see the future of Teenergizer now?

Today, me, my family and my country are facing the greatest crisis of our lives. So if I am not sure about tomorrow, it is difficult to see what the future holds. Over the years, we built a real family, teams of young Teenergizer leaders in different cities in eastern Europe and central Asia—in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, even in Russia. But now we are divided. After the Second World War, Winston Churchill said that there would be a wall. And I think that a new wall is appearing now.

What would you say today if you were again on the podium of the United Nations General Assembly?

This is a war between the old world and the new world.

We are young people who want to live in a new world, where there are no wars, where pandemics such as HIV, tuberculosis and COVID-19 are ended, where poverty and climate change are solved. In this new world, all people, no matter who they are or who they love, whatever language they speak or what passport they hold, can enjoy freedom and live their life with dignity, and travel and move across open borders, between peaceful countries. We learned how important and precious this was in recent years when Ukrainians could travel. We could see how peace-loving people lived in other parts of the world, and it made us appreciate the beauty and freedom we have in Ukraine. Today, more than ever, we only understand what we want to rebuild in our own country when we compare it to the values we find in other countries.

And it is this old world that is financing and sustaining this war. This is a road to nowhere.

With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises.

The new world is about development, not destruction. It is about being able to improve yourself, improve the quality of your life and really support others to do the same.

Everything has an end. And the war will eventually end. What will you do on the first day after the end of the war?

I'll start to read Leo Tolstoy’s book War and peace.

Region/country

Related

Press Statement

UNAIDS welcomes parliament’s decision to repeal the law that criminalizes HIV transmission in Zimbabwe

18 March 2022 18 March 2022GENEVA, 18 March 2022—UNAIDS congratulates Zimbabwe’s parliament for repealing section 79 of the Criminal Law Code, which criminalizes HIV transmission. A new marriage bill adopted by parliament that repeals the criminal code section is to be signed into law by the president. The criminalization of HIV transmission is ineffective, discriminatory and undermines efforts to reduce new HIV infections. Such laws actively discourage people from getting tested for HIV and from being referred to the appropriate treatment and prevention services.

“Public health goals are not served by denying people their individual rights and I commend Zimbabwe for taking this hugely important step,” said UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima. “This decision strengthens the HIV response in Zimbabwe by reducing the stigma and discrimination that too often prevents vulnerable groups of people from receiving HIV prevention, care and treatment services.”

UNAIDS has worked closely with Zimbabwe’s National AIDS Council, Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, parliamentarians, civil society activists and communities to advocate for the repeal of the law criminalizing HIV. Overly broad and inappropriate application of criminal law against people living with HIV remains a serious concern across the globe. More than 130 countries worldwide still criminalize HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission through either specific or general criminal legislation.

In 2019, Zimbabwe completed a legal environment assessment, which identified the criminalization of HIV transmission as a barrier to health care and a driver of stigma and discrimination for people living with HIV and other key populations. Since then, the United Nations Development Programme has worked with key populations and other stakeholders, convening meetings with parliamentarians and other partners to advance the recommendations of the legal environment assessment.

In 2018, UNAIDS, the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care and the International AIDS Society convened an expert group of scientists who developed an Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the Context of Criminal Law. The statement calls on the criminal justice system to ensure that science informs the application of the law in criminal cases related to HIV.

Zimbabwe has made great progress in the response to HIV over the past decade. It is estimated that 1.2 million of the 1.3 million people living with HIV in the country are now on life-saving medicines. AIDS-related deaths have decreased by 63% since 2010, with new HIV infections down by 66% over the same period.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

Quick thinking and planning instrumental for HIV network in Ukraine

08 March 2022

08 March 2022 08 March 2022When shelling awoke Valeriia Rachynska in Kyiv on 24 February, the first day of the conflict, she rolled over and tried to get more sleep. As a native of Luhansk, she had already lived through the 2014 conflict.

“I think my brain analysed the noise and realized I was out of harm’s way,” she said by videoconference from a small village in western Ukraine. “But when I saw my kids crying and frightened, I knew I had to relocate yet again.”

The following night she and her two sons stayed in a bomb shelter and then left their home in the capital city with her brother and his family.

As the Director of Human Rights, Gender and Community Development of 100% Life, the largest network of people living with HIV in Ukraine, she stressed that in order to continue helping people, she needed to relocate to a safer place.

“It’s like when you are in an airplane and there is a lack of oxygen,” Ms Rachynska explained. “You put the mask on yourself first then place it on others afterwards.”

The key for her and her organization was being able to have Internet access, a steady mobile phone service, open banks and a relative sense of safety. These days she felt like she was operating a switchboard.

“I respond to all calls and try to redirect them to the right people,” she said. “It has been non-stop and because there are so many attacks and so much unpredictability, I can only advance one step at a time.”

She credits 100% Life’s head, Dmytro Sherembey, for having done advance planning ahead.

“A lot of people told us, “You are crazy to panic,” but at 100% Life we moved our computer servers, documents and anything deemed sensitive to western Ukraine and even Poland and Germany.”

Some of her colleagues stayed in Kyiv saying they would tough it out, but 10 days later many of them left too.

“We are now focusing on evacuations and relocation for people living with HIV and their families as well as marginalized groups by hiring buses for them,” Ms Rachynska said, wrapped up in a blue sweatshirt with a hood. “For those not living in Kyiv, we are sending money via bank transfers for them to buy food and other essentials.”

The country has enough buffer stocks of HIV medications to last until April, but with the help of international partners and UNAIDS’ coordination, 100% Life has urgently planned to have additional life-saving medicines delivered to Poland. The Polish Government has secured a warehouse and agreed to help with logistics, getting antiretroviral therapy to people living with HIV in Ukraine.

Ukraine has the second largest AIDS epidemic in the region. It’s estimated that 250 000 people live with HIV in Ukraine, with more than half on antiretroviral therapy, medication that needs to be taken daily for people living with HIV to stay healthy.

“Our biggest challenge right now is to save lives, provide security and have people stay on treatment,” she said. The 100% Life network has already redesigned key aspects of its programme to get funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to meet the immediate needs.

Having joined 100% Life in 2011, Ms Rachynska has seen the strides that Ukraine has made to reverse the AIDS epidemic. She is particularly proud of the positive impact that harm reduction programmes, including opioid substitution therapy and needle–syringe exchanges, have had in Ukraine to reduce new HIV infections. HIV in the country continues to disproportionately affect people who inject drugs and the ongoing military offensive may hamper substitution therapy options. She said that 100% Life was actively working to avoid that.

Her other worry involved protecting sex workers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people and people who inject drugs. Based on the violence and stigma those groups experienced during the conflict in eastern Ukraine, she fears that key populations will be the targets of violence.

“Our next task will be to start and monitor human rights violations,” she said. “This is very important to me.”

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

The case for anti-discrimination legislation in Jamaica

01 March 2022

01 March 2022 01 March 2022Michael James (not his real name) was shell-shocked when he was fired. He scanned the dismissal letter. It cited his performance and tardiness as reasons for the job loss. But years of performance appraisals told a different story. He’d consistently received positive evaluations and there were no memos about late-coming or substandard work on his file. The only reason he could discern was that colleagues recently learned that he was living with HIV.

HIV-related prejudice remains rife in Jamaica. One third of people living with HIV responding to the 2020 Jamaica People Living with HIV Stigma Index reported experiencing stigma and discrimination. Verbal harassment, gossip and discriminatory remarks were the most common violations. But one in 10 said they were refused employment or lost a source of income because of their HIV status. No legislation prohibits a Jamaican employer from discriminating on the basis of HIV status.

This has marked implications for the HIV response. Twenty-one per cent of respondents were worried about mistreatment or confidentiality breaches by health-care workers. Thirty-eight per cent delayed testing and 29% delayed starting treatment because of concerns about how they would be treated.

Shelly John (not her real name) recounts hopping from one treatment site to another before landing at Jamaica AIDS Support for Life. At other facilities she overheard nurses gossiping about patients’ medical histories.

“I felt uncomfortable. If I am hearing about other clients, other clients can come inside and hear about me as well,” she reasoned.

“The fear of stigma drives some persons underground and away from much needed health services. Owing to stigma and discrimination, some persons delay accessing needed services and, as a result, some are diagnosed with HIV at an advanced stage,” acknowledged State Minister in the Health and Wellness Ministry and Chair of the Jamaica Partnership to Eliminate HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination, Juliet Cuthbert Flynn.

Jamaica’s testing and treatment outcomes bear this out. While an estimated 86% of people living with HIV were aware of their status in 2020, just 40% of people living with HIV were on HIV treatment.

While the Jamaica Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedom guarantees protection against discrimination, it is limited in scope. The protected grounds are race, sex, place of origin, social class, colour, religion and political opinions. There are piecemeal anti-discrimination provisions in different pieces of legislation, such as the 2014 Disabilities Act and the 1975 Employment Act. But neither the constitution nor ordinary legislation make discrimination on other grounds unlawful.

Since 2020, UNAIDS and the United Nations Development Programme have been providing technical and financial support to local nongovernmental organizations, including Jamaica AIDS Support for Life, to support the rollout of a national survey on the public’s perspectives and experiences with stigma and discrimination in Jamaica and on the need to have more adequate protections in the law. The results of the survey will be used to advocate for legislation to adequately deal with discrimination experienced by vulnerable and marginalized groups.

The proposed legislation should provide protection across areas including discrimination based on health status, pregnancy or childbirth, hiring or termination decisions and the denial of services to minority groups. It should also address discriminatory conduct based on assumptions about a person’s competence, capabilities, age, self-expression, income level, the neighbourhood in which they live or their educational background.

“Comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation will strengthen the legal framework for the protection of human rights towards achieving equality for all,” Manoela Manova, the UNAIDS Country Director for Jamaica, explained.

In real terms, this means that duty-bearers will have to consider how their policies, programmes and services will affect people with the protected characteristics. Critically, the focus on markers related to poverty would mean that for the first time public bodies will have a duty to consider socioeconomic disadvantage when making strategic decisions about how to exercise their functions and when proposing to use public funds.

“Our overarching finding has been that regardless of health status, sex, age or sexual orientation, the factor that fuels discrimination and makes people more vulnerable is poverty. Moving forward, it is critical that we don’t treat HIV as a stand-alone concern but address the full picture of what makes people marginalized and vulnerable in Jamaica,” said UNAIDS Community Support Adviser for Jamaica, Ruben Pages Ramos.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“An HIV diagnosis should not be a guilty verdict—it’s just a diagnosis"

01 March 2022

01 March 2022 01 March 2022Nargis was born in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, into a large family. Life was not easy, and she was sent to a boarding school for low-income families. Her favourite subject at school was physical education, excelling at basketball and swimming. She hoped that after graduating from school in 1991 with a diploma in physical education she would continue her studies at a technical school.

However, because of unrest in the country, she couldn’t carry on with her schooling. “I cried for six months, I really wanted to continue my studies, but instead of going to a technical school, my parents married me off. I was not yet 16 years old then,” said Nargis. When she was 17 years old, she gave birth to a son; five years later, while pregnant with her second child, she learned that her husband was involved in drug trafficking, and he was sent to prison.

From that time on, Nargis had to provide for herself and her family on her own. She got a job in a casino. The earnings were good, but it was there that she started taking drugs. “I was a shy girl, so to make me feel relaxed, I used drugs. From there, I became a drug addict. I didn’t even notice how it happened,” she recalled.

She was eventually fired from her job because of her drug-taking and was forced to look for other ways to survive.

Nargis injected drugs for 14 years, but she started on opioid substitution therapy when it was made available in the country. “While I was on methadone, I was hired as a peer counsellor. I worked with drug users, with people living with HIV. I worked as a consultant in several HIV prevention projects,” said Nargis.

Nargis remained on methadone until May 2021. “Last year, I had to stop methadone because I was sent to prison and there was no methadone in prison. It was very hard, I was in the prison hospital for several months, but as a result I got off methadone and, so far, I am holding on.”

Nargis was imprisoned under Article 125 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan, under which it is a criminal offence to infect someone with HIV or to put them at risk of HIV infection. Based on this article, law enforcement agencies initiate criminal cases against people living with HIV just on the basis of the potential threat of HIV transmission or simply just based on their HIV-positive status.

“I have been taking antiretroviral therapy since 2013. I have never interrupted it. I have an undetectable viral load. No one wrote a statement against me. I did not infect anyone. The accusation was made on the basis of a note from a man I knew, because we were dating,” Nargis said.

The legislation does not take into account the informed consent of the other sexual partner, regardless of whether there was a risk of HIV infection, or whether the person living with HIV takes precautions against HIV transmission. In addition, the legislation does not define how someone living with HIV should declare their HIV status. In effect, all people living with HIV who have sex can be held criminally liable.

Nargis explained her shame, “Law enforcement agencies called everyone, doctors, my colleagues, relatives, and told them about my HIV diagnosis, asked what kind of relationship we were in, dishonoured me.”

“Article 162 of the Health Code gives doctors the right to disclose the status of HIV-infected patients at the request of the investigating authorities, and does not contain any justification for this. Some criminal cases under part 1 of Article 125 were initiated after the HIV clinic disclosed information about HIV to law enforcement agencies. During the investigation and trial, the defendants’ right to confidentiality regarding their HIV status is not ensured, since investigators, officials, court clerks and judges can request medical information in accordance with the provisions of the Health Code without any specific conditions,” said Larisa Aleksandrova, a lawyer.

Nargis is now free, but she said that she was just lucky. “I was released under an amnesty in connection with the 30th anniversary of the republic.”

She is out of prison, but there are still dozens of other people convicted under Article 125. Now that everyone knows that she is living with HIV, Nargis is ready to fearlessly fight for the right to live, work and love, despite her HIV status.

Nargis continues to work as a volunteer peer consultant on HIV prevention. She has many plans, but the main goal that she is striving for is the revision of articles criminalizing HIV in Tajikistan.

“I always say that there should be more information about HIV, about people living with HIV, so that they don’t fear us the way they do now. Now everything has changed, there is treatment, there is prevention. An HIV diagnosis should not be a guilty verdict—it’s just a diagnosis.”

Most countries in the eastern Europe and central Asia region have criminal penalties and various types of punishment, including imprisonment, for concealing a source of HIV infection, for putting someone at risk of HIV or for transmitting HIV. HIV criminalization disproportionately affects marginalized populations, especially women. Women are more likely to find out their HIV status when accessing health care, such as for pregnancy, and are more likely to be criminalized and punished.

“We know for certain that laws that criminalize HIV are counterproductive, undermining rather than supporting efforts to prevent new HIV infections. We hope that by consolidating the efforts of governments and public organizations it will be possible to revise outdated laws in the near future, taking into account the latest data on HIV, which will allow people living with HIV, or those who are most at risk of infection, to be open in their relationships with medical organizations, to disclose their HIV status and use affordable medical services,” said Eleanora Hvazdziova, Director, a.i., of the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV programmes in Tajikistan

Status of HIV programmes in Tajikistan

05 March 2025

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

“My life’s mission is to end stigma and discrimination, and that starts with U = U”: a story of HIV activism in Thailand

01 March 2022

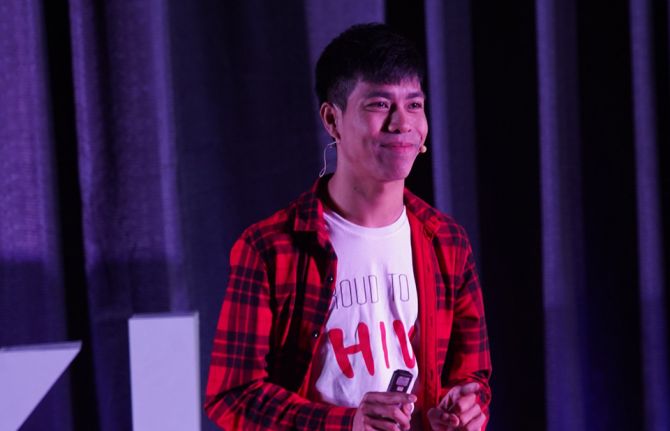

01 March 2022 01 March 2022Like any other regular day in Bangkok, Thailand, Pete went to work and was living a pretty normal life. He had a business that imported and exported fresh vegetables from neighbouring countries in South-East Asia, a family business that he shared with his sister. He was happy and in a serious long-term relationship with his boyfriend, and everything seemed perfect. That day, he and his partner went to get tested for HIV, and that’s when his life suddenly began to change.

“I found out about my HIV status in 2016 and soon after left my business because I didn’t know if I was going to live much longer. Without guidance and mental health support, I had many misconceptions about HIV, and I started to suffer from depression,” he said.

“I blamed myself for contracting HIV, and I couldn’t cope with this thought. I became a drug user, was engaging in chem sex, broke up with my partner and survived suicide attempts,” he continued. “But after receiving support from local organizations of people living with HIV, I decided to retake control of my life. I started to talk openly about HIV to help other young people live with a positive diagnosis. Even though this was never my plan, I knew I had to do it. That’s why I became an HIV activist,” he added.

Nowadays, Pete (famously known online as Pete Living with HIV) is a well-known HIV activist in Thailand and has come far since his diagnosis. He has spent the past few years building an online community for people living with HIV. In this safe space, people can connect and be comfortable enough to share their stories and experiences in an open environment free from stigma and discrimination. His Facebook group, which has strict membership requirements (for obvious reasons), has more than 1300 members.

“I created this space because I didn’t have a place to share my story. I wanted to create a platform where people living with HIV can be proud of themselves and be reminded they are not alone. No one deserves to be stigmatized, bullied, dehumanized or disrespected. Everyone deserves to be loved, respected and accepted,” he said.

In 2019, the country announced the Thailand Partnership for Zero Discrimination, which calls for intensified collaboration between the government and civil society to work on stigma and discrimination beyond health-care settings, including workplaces, the education system and the legal and justice system. UNAIDS has been involved since the outset of the initiative by providing technical assistance to formulate the zero discrimination strategy and the five-year action plan, develop a monitoring and evaluation plan and operationalize the strategy as a joint effort between the government and civil society.

Pete thinks this initiative is a cornerstone to ending the AIDS epidemic, as stigma and discrimination continues to be the main barrier to HIV services. “Although it has improved a lot over the years, I still experience stigma and discrimination when I go for regular sexually transmitted infection check-ups. I still receive judgement from nurses and doctors,” he said.

Pete has also become a passionate activist for, and speaks about the importance of, U = U (undetectable = untransmittable) at international forums and conferences. “U = U changed my life. I continue to fight for and promote U = U because its messages have the power to change the lives of people living with and affected by HIV. Still, more importantly, it can change social attitudes and tackle stigma and discrimination,” he said.

With U = U, HIV treatment has transformed the HIV prevention landscape. The message is clear and life-changing: by being on HIV treatment and having an undetectable viral load, people living with HIV cannot transmit HIV to their partners. The awareness that they can no longer transmit HIV sexually can provide people living with HIV with confidence and a strong sense of agency in their approach to new or existing relationships.

Pete launched a campaign in 2020 focusing on U = U and mental health advocacy. “Through my social media channels, I raise awareness about the importance of listening to people and their experiences and respecting them. U = U is key to helping people living with HIV overcome self-stigma and negative feelings like shame, which discourage them from accessing and/or remaining on treatment. U = U is encouraging; it can help remind people living with HIV to be proud of themselves,” he said.

Pete is now strengthening partnerships with national stakeholders and allies of the HIV response to ensure that messages related to U = U, HIV prevention and zero discrimination are amplified and reach different audiences. He is also a representative on a multisectoral task force to design and implement the People Living with HIV Stigma Index in Thailand, which will be conducted this year. He has supported the United Nations in Thailand on various campaigns, including the Everybody Deserves Love Valentine's Day campaign and the zero discrimination campaign, in which he is engaging young people from across Thailand.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“Play with your heart”— Kazakh women living with HIV tell their stories from the stage

14 February 2022

14 February 2022 14 February 2022The ARTiSHOCK Theatre in Almaty, Kazakhstan, recently premiered an extraordinary performance: all its actresses were women living with HIV, ex-prisoners and women who use drugs. They played the role of women who faced stigma, discrimination and violence, an echo of their own life stories.

The performance, the script for which was written by female activists, was the idea of the Revanche Center for Comprehensive Care (also known as the Revanche Foundation), supported by the UNAIDS Country Office for Kazakhstan and the Eurasian Network of Women Living with HIV.

“The idea of a social theatre was a dream that has finally become a reality,” said Anna Kozlova, a social worker for the Revanche Foundation. “We decided to talk about the experience of violence. After all, it is not only physical or sexual. To be rejected by society and discriminated against is also violence, but psychological.”

Nadezhda Plyaskina, the play’s director, said that it was not easy to work with the aspiring actresses. “I was afraid: these women have such considerable life experience; what can I teach them? In addition, it was necessary to teach acting in a way that did not hurt: they are all vulnerable. Each rehearsal revealed them to me as real, amazing, wonderful people. I told them: “Play with your heart.””

And they played with their hearts, telling their stories of imprisonment, abuse, stigma, loneliness and hope. The performance was a great success and was widely covered by Kazakh media.

Ms Kozlova began using drugs when she was 17 years old, which landed her in prison for 17 years. “All women who come out of prison are already victims. They are broken, vulnerable, don’t know how to live, where to go. They need help to become strong.” Four years ago, she went to the Revanche Foundation for help, and there she found a job, a family and a purpose. “I know from my experience that things can change,” she said.

Zulfiya Saparova has been living with HIV for 15 years; she is on antiretroviral therapy and works as a peer consultant for Equal to Equal Plus. She faced abused and violence and tells her story from the stage. “My heroine in the performance comes on stage holding a frying pan. This story is imprinted in my memory: my neighbour constantly walked around with black eyes. She was beaten by a drunken husband. Once her daughter came to visit her, and a black eye appeared on the husband’s face—she had protected her mother by beating him with a frying pan.”

Natalya Kovaleva, a social worker for the Revanche Foundation, spent eight years in prison. Her last term was three years and compulsory treatment for drug addiction. Currently, she works with young people who use drugs on HIV prevention. “If it wasn’t for the Revanche Foundation, I would either be behind bars or dead,” she said. “I have a mission here.”

The heroine she plays faces physical and psychological violence, total control, prohibitions and beatings. “I don't want to arouse pity, so I played a strong, independent woman who refuses to endure bullying. All this was in my own life,” said Ms Kovaleva.

The Revanche Foundation helps women in difficult situations, including women living with HIV, women who use drugs, children who lived in orphanages and former prisoners.

Elena Bilokon, the director of the Revanche Foundation, says that her work is focused on the most vulnerable and socially unprotected women, as there are no state support programmes for them. “Yes, the state provides patients with HIV drugs, but there is no psychosocial and social support. This year alone, 285 women living with HIV applied for our help,” she added.

“There is a clear link between violence against women and HIV. Studies show that women living with HIV are more likely to have experienced violence, and women who have experienced violence are more likely to be living with HIV,” said Gabriela Ionescu, the UNAIDS Country Director for Kazakhstan. “For this reason, UNAIDS highlights the need to address violence against women as a key human rights issue and the need to provide support to the most vulnerable women, including social and psychological help.”

The next performance will take place on 1 March, Zero Discrimination Day. The activists also plan to perform the play in several prisons in Kazakhstan.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS saddened by the death of Joe Muriuki

18 February 2022

18 February 2022 18 February 2022By David Chipanta, UNAIDS Senior Adviser, Social Protection

Joe Muriuki was a son of the African soil, born and raised in Kenya, a local, national and global advocate for the right of people living with HIV to access life-saving HIV treatment free from stigma and discrimination. In 1987, he became the first Kenyan and among the first of all people living with HIV in Africa to share publicly that he was living with HIV.

Mr Muriuki died from oesophagus cancer-related complications on 14 February 2022, having lived a healthy life with HIV for more than 36 years, thanks to his access to life-saving HIV treatment and through living his life with a sense of purpose.

Mr Muriuki fought against AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in his native Kenya at a time when an HIV diagnosis was thought to mean imminent death. He offered a testimony that a healthy life with HIV was possible. He formed the first support group of people living with HIV in Kenya, the Know AIDS Society, to encourage people living with HIV to overcome fear, stigma and discrimination and to advocate for changing policies and laws to remove AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

After his HIV diagnosis, stigma and discrimination forced Mr Muriuki to leave his job, and he returned to his home city, Nyeri, to await his death. In Nyeri, the stigma and discrimination he experienced stopped him from opening a bank account. However, he overcame the obstacles in his path and decided to dedicate his life to a crusade against HIV. His courage and conviction to openly disclose his HIV status, and to fight AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, were heroic.

His campaigning also formed the foundation of Kenya’s national AIDS response, prompting the government to declare AIDS a national disaster before establishing the National AIDS Control Council in 1999. Mr Muriuki was also active globally, advocating for access to life-saving HIV treatment for people living with HIV in Africa and their greater involvement in the AIDS response. He served in the Network of African People Living with HIV, the Global Network of People Living with HIV, the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and the Pan African Treatment Movement, among other organizations, advocating with candour for equitable access to HIV treatment for people living with HIV in Africa.

Although Mr Muriuki’s HIV was virally suppressed, from 2018 he struggled with cancer, eventually dying from its complications. He was worried that the AIDS response was ignoring noncommunicable diseases and in his work with Kenya’s HIV Tribunal he pushed for noncommunicable diseases to be brought to the forefront of the AIDS response.

Mr Muriuki will be sorely missed by his family, friends and colleagues in Kenya and around the world.