Feature Story

Human touch and targeted screening help to reduce HIV outbreak in Athens

16 March 2018

16 March 2018 16 March 2018Greece experienced a large increase in 2011 in the number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs. The number of new diagnoses in Athens usually hovered around 11 per year, but shot up to 266. For the first time, injecting drug use and sharing needles became the main source of new HIV infections in Greece, according to the Medical School of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

In response, the university, along with the Greek Organisation against Drugs and other nongovernmental organizations, launched a programme to “seek, test, treat and retain”, under the name Aristotle, in order to put a halt to the outbreak.

Their first challenge was finding people who inject drugs and identifying if they were HIV-positive.

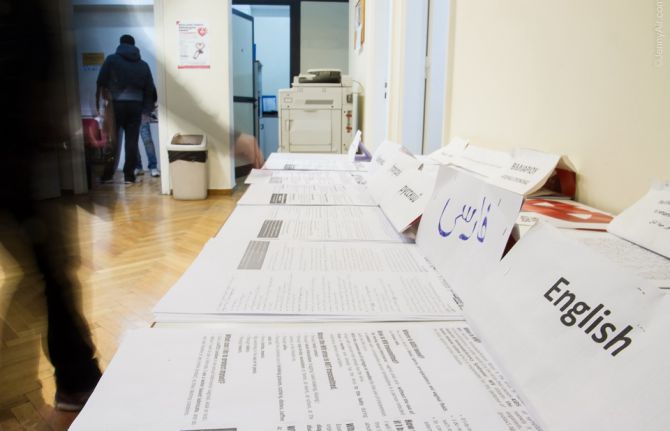

“Many lived on the streets, some had been in prison and in many instances they were migrants with no knowledge of Greek,” said Vana Sypsa, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and a lead on Aristotle, along with Angelos Hatzakis, Meni Malliori and Dimitrios Paraskevis.

She explained that because of the economic recession, people lost their jobs and shared injecting equipment with other people, and homelessness crept up. In addition, she added, sterile syringes were hard to come by and opioid substitution therapy centres had long waiting lists. The Aristotle programme used a coupon system so that peers could recruit people to come in for an HIV test in return for a stipend.

Ms Sypsa explained that the centre provided food, as well as condoms and syringes. Positive Voice, an association of people living with HIV, helped with HIV counselling, while Praksis focused on facilitating language services and identity papers for migrants.

Nikos Dedes, the head of Positive Voice, said that it played an active role during the diagnosis and referral part of the programme. “We guided them through the maze, which increased the retention of people,” he said. Mr Dedes believes that Aristotle contributed to raising awareness of HIV among people who inject drugs. “For many, HIV was a wake-up call to dealing with their drug addiction,” he said.

The programme had five rounds of recruitment in 2012 and 2013, with some participants taking part in more than one round. Aristotle’s services were provided to more than 3000 people. About 16% of the participants tested positive for HIV and had the opportunity of immediate access to antiretroviral therapy, with social workers arranging appointments. They also had priority access to opioid substitution therapy.

Ms Sypsa said that even before the end of the programme, there was a 78% decline in new HIV infections in Athens.

“Aristotle averted 2000 new HIV infections and we noted a decrease in high-risk behaviour among people injecting drugs at least once a day,” Ms Sypsa said.

She added that aside from containing an outbreak, all those involved in the programme were proud to have changed the lives of many people, linking them to HIV care and treatment.

The programme’s success drew a lot of attention. After the end of the programme, “People kept stopping by the site, looking for Aristotle employees. We had become a reference point for them,” she said.

Five years later a new programme is being started, but this time with an aim to increase care and treatment for HIV and hepatitis C for people who inject drugs.

And Mr Dedes is ecstatic, because this time Positive Voice is an integral part of the programme, with a budget. A new partner has also joined—the liver patient association Prometheus will spearhead the response to hepatitis. Mr Dedes said, “This is a true testament to the success of the programme—incorporating people from the communities.”