Feature Story

Urgently needed HIV services are supporting Ukrainian refugees in the Republic of Moldova

07 April 2022

07 April 2022 07 April 2022Many of the Ukrainian refugees seeking sanctuary in the Republic of Moldova are from Odesa or the surrounding region, which is one of the regions of Ukraine most affected by HIV.

Iryna Kvitko (not her real name) fled with her entire family, including her daughter-in-law and young grandson, to the Republic of Moldova. She said that an air-raid siren would sound several times a day, terrifying her grandson. “We thought about whether we should go or not, but it was scary to sit all night in our home—me, my husband, son, daughter-in-law and grandson—and try to explain to the child what the explosions and sounds of shooting were. Plus, to be honest, I was very afraid of the situation regarding my antiretroviral therapy—I was running out of it and it was not clear what would happen next.”

Ms Kvitko has been living with HIV for more than 15 years but keeps her diagnosis a secret. “I work, we live decently. I have a family, children, relatives, friends, colleagues. God forbid that someone would find out—it would all go to dust,” she said.

She described her difficult journey to the Republic of Moldova—there was widespread panic and at the border checkpoints the queues of traffic reached up to 80 kilometres. “Many people just got out of their cars and walked. Our main goal was to take our children and grandson out of Ukraine,” she said.

“My doctor in Odesa gave me information on where people can go to get help with antiretroviral therapy. I called them and after they took my contact number they immediately called me back and explained where to go and what to do and said that they would help me and give me the medicines I need.”

On the very first day of the war, Ihor Plamos (not his real name), together with his wife and child, drove to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa. There were a lot of people at the border, he recalled. “As soon as we got to our destination, I started to drive back to the border, to give a lift to people who had travelled on their own, who had walked seven or eight kilometres.” He took them to an aid distribution centre, from where they travelled on to Georgia or Germany.

“When we arrived, we didn’t know what to do. So, I called my doctor in Ukraine, and she told me where to go,” he said.

The clinic that his doctor referred him to tested his viral load free of charge, and the doctor prescribed antiretroviral therapy for him. He does not want anyone to know that he is living with HIV, noting that the level of stigma around the virus remains very high. “Therefore, I was worried at the beginning about what would happen to my treatment,” he said.

Hanna Brovko (not her real name) travelled to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa with her 11-year-old son, leaving behind her sewing business, clients and friends. She has been living with HIV for more than 12 years, but she does not tell people about her diagnosis. “I don’t need pity, and I don’t want things to be said about me behind my back.”

She received all the necessary medicines upon her arrival in the country but decided to move on to Germany. Berliner Aids-Hilfe helped her to arrange her flight from Chisinau to Berlin, set up her in a family’s house and arranged medical insurance, which is necessary for her to obtain her HIV treatment.

Elena Golovko, an infectious diseases doctor at the Hospital of Dermatology and Infectious Diseases in Chisinau, emphasized that people who come from Ukraine receive all HIV services in the same way that Moldovan people living with HIV do. “Today, we have a person living with HIV hospitalized, there are several HIV-positive women, there are those who have already given birth here and who received syrup to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. There is also a person receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis. We issue a 30-day supply of antiretroviral therapy to refugees. If people stay longer in the country, they can come and receive a refill. We don’t have any problems with ensuring the same level of HIV services,” she said.

However, she added that some people did not know their latest test results or could not remember the name of the medicines they take. “It was important for us to establish communication with colleagues in Ukraine, especially fast communication when a person is directly in the clinic.”

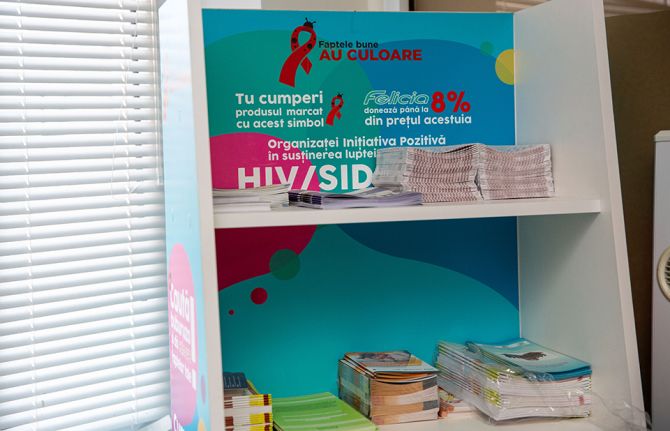

Alina Cojocari, the coordinator of assistance for people living with HIV at the Positive Initiative nongovernmental organization highlighted that it is fully involved in service delivery for refugees in need of HIV services. “We are referring people to health services, supporting them with accommodation in the country and offering them psychosocial and legal support,” she said. “For those travelling from the Republic of Moldova to other countries, we ensure they are linked to HIV services in the next country,” she added.

“This level of HIV services for refugees living with HIV in the Republic of Moldova became possible as these services in the country have long been built around people’s needs,” said Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Country Manager for the Republic of Moldova. “This approach is now also being used for refugees. During humanitarian crises, such as the war in Ukraine, everyone is vulnerable and people fear for their loved ones. For people living with HIV, there is also the fear of not receiving timely, life-saving HIV treatment, and in many cases the fear of the disclosure of their status. That is why it is so important to create sustainable, agile, equitable health and social protection systems with people at the centre, which can protect people during a crisis.

Region/country

Related

Ukraine: Keeping people in care

Ukraine: Keeping people in care

23 February 2026

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025