Feature Story

Learning skills for life in Namibia

10 April 2017

10 April 2017 10 April 2017During their visit to Namibia, President George W. Bush and Ms Bush visited the Ella du Plessis High School in Windhoek to see how students are learning the life skills they need to help them make responsible decisions as they transition into adulthood.

The students had a lively discussion with their high-profile guests, explaining how the classes helped to teach them respect for others and expose them to sensitive issues, such as unintended pregnancy, HIV infection and gender-based violence. Answering a direct question from President Bush, male students in the class said the classes taught them respect for young women.

The First Lady of Namibia, Monica Geingos, and the Executive Director of UNAIDS, Michel Sidibé, accompanied President Bush and Ms Bush on the visit. Mr Sidibé praised President Bush for setting up the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

“When President Bush established the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in 2003, just 50 000 people in Africa were accessing medicines to keep them healthy and alive,” said Mr Sidibé. “Today, more than 12 million people in Africa, and 18 million globally, are accessing antiretroviral medicines.”

President Bush encouraged young people to get tested for HIV, learn how to protect themselves from the virus and get treatment if necessary.

During the visit, Ms Bush announced that the Laura Bush Foundation for America’s Libraries planned to fully stock the Ella du Plessis High School’s library. The first books donated were a book of paintings by her husband and her daughter Jenna’s book called Ana’s story: a journey of hope.

The school’s life skills class is part of the First Lady of Namibia’s Be Free campaign, which encourages young people to talk about sensitive issues facing them and to seek help and guidance to help them navigate life choices.

When Pres Bush set up @PEPFAR in 2003 50K ppl in #Africa had access 2 life-saving meds. Today 12M in #Africa are on treatment. #legacy pic.twitter.com/cJ9TvINVa3

— Michel Sidibé (@MichelSidibe) April 6, 2017

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Ghana—addressing the barrier of stigma and discrimination for women

27 March 2017

27 March 2017 27 March 2017Patience Eshun, a widowed grandmother from Ghana who lost her daughter last year to HIV, knows how destructive HIV-related discrimination can be. “My daughter refused to go hospital to receive medicines. My daughter died because of the fear of stigmatization and discrimination,” she said.

Ms Eshun is one of thousands of widows living in Ghana who have experienced the effects of stigma and discrimination on people living with HIV. Ms Eshun and a group of women joined UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director Jan Beagle at a dialogue organized through the Mama Zimbi Foundation (MZF)—a nongovernmental organization that seeks to empower and support widows through its Widows Alliance Network (WANE) project—to discuss the challenges faced by widows and women living with HIV.

Ms Beagle visited Ghana to engage with the government and other stakeholders in light of Ghana’s Chairmanship of the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board.

In Ghana, women are among the people most affected by HIV. Prevalence among women aged 15–49 is nearly double that among men of the same age (2.0% versus 1.3%). Widows are among the poorest women in Ghana—their poverty is linked to the deprivation of their rights and lack of access to justice through discriminatory customs, traditions and religious codes. Widows in Ghana are often faced with legal regulations that do not support the protection of their rights. Widows regularly lose land and possessions and are evicted from their homes once they lose their spouse. For widows living with HIV, stigma and discrimination is often exacerbated.

Responding to these challenges, Akumaa Mama Zimbi, a Ghanaian women’s rights leader, television and radio talk show host, launched a network (WANE) to support sustainable socioeconomic development for widows. The project equips widows in Ghana with employable skills, human rights education, reproductive health and social integration programmes. Through WANE, more than 400 widow groupings have been formed in Ghana, with membership swelling to more than 8000 nationwide. The organization also provides small income generating and training workshops for widows in dressmaking, bread baking, beekeeping and small-scale farming.

“We are passionately committed to striving for advocacy of a comprehensive policy and legal direction for elevating the standards of widows, and all women, in Ghana. We need to empower women, and make sure men are also fully part of the discussion—we need to work together for a better future,” Ms Zimbi said.

During the meeting, Ogyedom Tsetsewah, a Queen Mother (traditional community leader) and advocate for women’s rights, explained that if a widow is facing injustice, she has little or no recourse within her community and within the courts, and that traditional leaders have an important role to play. “There is a clear role for traditional leaders in advocating with the national political leadership on the situation of widows and the critical importance of investing in social protection of widows to allow them to contribute to community resilience,” she said.

Women and young people shared their experiences of HIV-related discrimination and hardship. It was a very honest discussion, where many women shared their own impressions of experiencing friends being stigmatized and discriminated against, even by themselves.

Ms Beagle commended the courage and resilience of the widows, while reflecting that, “Widows living with HIV often face triple discrimination: because they are widows, because they are women and because of their HIV status. Through economic empowerment, they become self-reliant and even leaders in their communities, can build awareness of HIV and stand up against stigma and discrimination.”

MZF is currently working on establishing a permanent location to provide vocational training, human rights education, reproductive health and social integration programmes for the daughters of vulnerable widows in Ghana. This initiative when implemented will provide skills and jobs for more than 3000 vulnerable young women.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

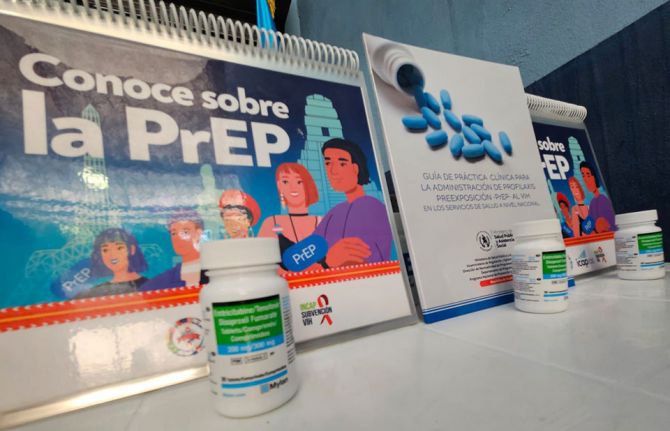

Claiming rights for transgender people in Latin America and the Caribbean

31 March 2017

31 March 2017 31 March 2017Transgender people are continuing to face widespread stigma, discrimination and social rejection in Latin America and the Caribbean. In most countries in the region, there is no legal recognition of transgender people’s affirmed gender identity. Without official documents that recognize their gender identity, transgender people are often denied access to basic rights, including the right to health, education, justice and social welfare. Transgender people are also more susceptible to violence, including physical and sexual violence.

Transgender women are also particularly affected by HIV. Estimates show that HIV prevalence for transgender women in the region range from 8% to 31% and there are few support programmes that address their specific needs. Where programmes do exist, they rarely include access to sexual and reproductive health services or HIV prevention, testing and treatment services.

However, the transgender community is increasingly speaking out about the challenges they face. Marcela Romero, Coordinator of REDLACTRANS, the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Transgender People, said, “Countries must take urgent steps to enact robust laws for non-discrimination with respect to gender identity and pass gender identity laws to guarantee access to education, work, housing and health services. These laws give transgender people the right to health and to access all the benefits and opportunities that any other citizen has. Without this right, we cannot access HIV prevention, care and treatment services.”

In 2012 in Argentina, REDLACTRANS and ATTTA, the Argentine association for transvestites, transsexuals and transgender people, played a key role in the passing of a law that gives transgender people the right to request that their recorded sex, first name and image be amended to match their self-perceived gender identity.

Such gender identity laws greatly improve the quality of life of transgender people. “In countries where legal recognition of affirmed gender identity has been achieved, transgender people are enjoying a higher life expectancy. Gender identity laws recognize transgender people as human beings—as citizens—put transgender people on the agendas of governments and reduce transphobia, stigma and discrimination,” Ms Romero explained.

The International Transgender Day of Visibility celebrates transgender people and raises awareness of the discrimination faced by transgender people worldwide on 31 March each year. To mark the day, Ms Romero has a simple but powerful message: “We do not ask for other rights—we ask for the same rights as any other citizen. A person who does not have an identity does not exist. We are part of society!”

UNAIDS is working to ensure that the target in the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS of ensuring access to combination prevention options to at least 90% of people by 2020—especially young women and adolescent girls in high-prevalence countries and key populations, including transgender people—is met.

Feature Story

British parliamentarians visit UNAIDS

31 March 2017

31 March 2017 31 March 2017UNAIDS welcomed a group of prominent British parliamentarians from the cross-party International Development Committee to discuss the role of lawmakers in ending AIDS and contributing to global health. The parliamentarians were Labour Member of Parliament and Shadow Secretary of State for International Development Kate Osamor, Stephen Twigg, Labour Member of Parliament and Chair of the International Development Committee, Conservative Members of Parliament David Mackintosh and Paul Scully, and Baroness Sheehan, member of the House of Lords and the Liberal Democrat spokesperson for international development.

Deputy Executive Director Luiz Loures chaired an informal discussion that began with the Members of Parliament sharing their own experiences of visiting AIDS programmes in Africa and Asia. They spoke of their acute awareness of the complicated nature of the AIDS response, and Mr Twigg highlighted the role that discriminatory laws played in creating barriers to services. Mr Loures noted that one of the biggest challenges to the AIDS response was the risk of complacency. Baroness Sheehan expressed her concern about the increased vulnerability of girls and young women. The discussion explored the role of civil society and the shrinking space for civil society and Mr Scully noted the increasing need to mobilize domestic resources.

Mr Loures highlighted the critical role of parliamentarians in ensuring that health and development international assistance is maintained and scaled up. Mr Mackintosh highlighted the need for increased efficiency and analysis on returns on investment to enable parliamentarians to advocate for sustained and increased funding.

Ms Osamor thanked Senior Adviser David Chipanta for sharing his personal story of living with HIV and the life-changing impact that access to treatment has had on his life.

The visit was organized by STOPAIDS, STOP AIDS Alliance, Results UK and Malaria No More. The United Kingdom is the fourth largest donor to UNAIDS.

Region/country

Feature Story

The incredible resilience of the people of South Sudan

30 March 2017

30 March 2017 30 March 2017Conflict has forced more than a quarter of the population of South Sudan to flee their homes, disrupted crop production and destroyed livestock. On 20 February 2017, famine was declared, which is already affecting 100 000 people, with a further 1 million people on the verge of famine. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, some 1.9 million people have become internally displaced and another 1.6 million people have crossed the borders as refugees.

One of the regions most affected by the crisis is Equatoria, which is also the region with the highest burden of HIV in South Sudan. Around 90% of the 20 000 people on antiretroviral therapy in South Sudan live in Equatoria, where conflict and food insecurity are pushing people across the border to Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in their thousands daily, and out of reach of essential health services.

Many people living with HIV are among the refugees. Even when medicine is available, food insecurity is affecting their ability to take it regularly, as humanitarian agencies are struggling to meet the needs of hundreds of thousands of people with very little funding.

The resilience of people living with HIV affected by the crisis is incredible, even in the most difficult of situations. John* is a refugee in a camp near Ajumani in Uganda and a member of the South Sudan Network of People Living with HIV.

“A number of us were running out of antiretroviral medicines, and where we are settled there are no health facilities providing HIV treatment,” said John. “So we put together the little money we had and sent one of us back to Nimule in South Sudan to collect medicines for all of us. Luckily the doctor allowed and we now have some medicines, but when they finish, what do we do?”

Whether displaced or not, the main problem facing people living with HIV in South Sudan is food insecurity. People in towns and cities are also affected, with the majority of vulnerable families only eating one meal a day, and some going without food for days.

Stigma and discrimination is making the situation even more acute, as women living with HIV are often abandoned and left destitute because of their HIV status. Jane, a young mother of three living with HIV in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, found out her HIV status when she was pregnant with her third baby. Her husband and family abandoned her and her children, two of whom are also living with HIV. Jane does not have full-time employment and is struggling for her and her children to have just one meal a day.

“These days we have to insist on one pill a day, as we only eat once a day, if we get food that day, and we cannot take these medicines on an empty stomach. Others have stopped taking the medicines because they have no food,” she said.

Despite facing numerous challenges in her life, Jane volunteers as a “mentor mother” to support prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services. She says of her work, “I like doing this, because we are many out there, but we fear discrimination if we disclose our HIV status. But with counselling, some of us are disclosing our status.”

In the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS, Member States committed to pursuing the continuity of HIV prevention, treatment, care and support and to providing a package of care for people living with HIV, tuberculosis and/or malaria in humanitarian emergencies and conflict settings, as displaced people and people affected by humanitarian emergencies face multiple challenges, including heightened HIV vulnerability, risk of treatment interruption and limited access to quality health care and nutritious food. UNAIDS is working with countries to ensure that the commitment is met.

* Names have been changed.

Resources

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Transforming lives through voluntary drug treatment

16 March 2017

16 March 2017 16 March 2017Hendro was a driver for a private company in Jakarta, Indonesia, when a colleague introduced him to heroin two years ago.

“I started to get addicted,” said Hendro, who prefers to use his first name only. “Soon, my body didn’t feel good if I wasn’t consuming drugs. I couldn’t concentrate. This lasted for about seven months before my life descended into chaos.”

His work suffered and he got into daily arguments with his wife. He would whisper to himself, “This is not right. I will destroy myself. Every day, I kept trying to stay away from drugs, but the craving for the drug was so painful. It was unimaginable.”

One day Hendro heard about an innovative drug programme based in a large house in Bogor, an hour outside of Jakarta. The cheerful building with a freshly cut lawn exudes a warm and friendly atmosphere, which is accentuated by two dogs who greet visitors with a couple of friendly sniffs.

Sam Nugraha founded Rumah Singgah PEKA in 2010. “PEKA is different from other treatment centres, because it is fully voluntary,” he said. “Every client has made their own decision to participate.”

There are 4 million people who inject drugs in the Asia and the Pacific region—that’s one third of the people who inject drugs globally. This places the region at the forefront of the largest injecting drug problem in the world.

A common response to drug use in the region is the confinement of people who inject drugs in compulsory treatment and rehabilitation centres.

“PEKA’s approach cannot be applied to everyone. Clients have to be conscious of what they need to do and ready to make changes,” said Mr Nugraha.

Before participants enrol in PEKA, they undergo a lengthy assessment to determine if the facility fits their needs.

“When I came to PEKA I was determined to recover and to rediscover the person who was lost because of drugs,” recalled Hendro.

Clients discuss with their counsellors the best treatment plan. They can choose to live in or outside of PEKA, but if they opt for the boarding option, they must respect the facility’s zero tolerance for the consumption of drugs while on its premises. Some clients select complete abstinence, others enrol in opioid substitution therapy and for those who wish to continue to inject drugs, PEKA has a needle and syringe programme. All clients are encouraged to have group and individual therapy sessions.

“Ninety per cent of our staff have experience with using drugs,” said Mr Nugraha, “so they understand the challenges clients are facing, as well as the type of support they need.”

Hendro decided to board and to participate in the methadone maintenance treatment programme. A counsellor accompanied him to a public clinic, where the doctor determined his optimal dose of methadone. He started off with 50 mg every day, but after a year has been bringing the dose down.

PEKA works in partnership with public clinics. Staff not only accompany clients to access methadone, but pick up a five-day supply of methadone for individuals who have established a steady routine and bring it back to the facility.

“Public health clinics have limited working hours and so we fill the gap by providing 24-hour services,” said Mr Nugraha. “People can come here at any time.”

Agustina Susana Iswati, Head of the Gedung Badak Health Clinic, agreed. “The cooperation with community groups is very much needed as they know what is really happening.”

People who inject drugs are vulnerable to HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs is higher than 30% in several Asian cities. Only 30% of people who inject drugs in Asia and the Pacific know their HIV status.

“We offer all our clients access to HIV testing. If the test result is positive, we help them start antiretroviral therapy as soon as possible,” said Mr Nugraha.

Evi Afifah, who is with the Mahdi Bogor Hospital, finds the collaboration with PEKA on HIV services helpful. “PEKA helps us reach our friends who are most in need of HIV testing, treatment and care,” she said.

Since 2010, PEKA has provided a range of services to almost 1000 clients. Follow-up surveys conducted with people who went through the full treatment programme indicate promising results. A significant number of clients reported that their drug dependency and quality of life had improved and their involvement in criminal activities had sharply declined.

This success has won local recognition. The organization was recognized by the Mayor of Bogor as an excellent institution in 2014 and 2016.

“PEKA is an organization that has gone through the test of time,” said Bima Arya Sugiarto, Mayor of Bogor. “With its vast experience, PEKA deserves our recognition, which can also motivate other community groups to be consistent and focused in their work.”

Perhaps the most important endorsement for PEKA is its clients, some of whom now work for the organization.

Iko, who is an HIV peer counsellor, said, “Aside from helping other people who use drugs, I am actually helping myself. That’s the main point. It makes me happy.”

After nine months of living at PEKA, Hendro was able to return home to his family and start working again as a driver. His experience was life-changing.

“At PEKA, I felt embraced as part of a family again. When I was using drugs, I was estranged and abandoned. Here, I found strength again,” said Hendro.

UNAIDS is working to support countries to reach the targets set out in the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS, which include ensuring access to combination HIV prevention options, including harm reduction, for 90% of people who inject drugs.

Multimedia

Region/country

Feature Story

Stopping the rise of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs

16 March 2017

16 March 2017 16 March 2017As part of UNAIDS’ efforts to stop the rise of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs UNAIDS is taking an urgent message to the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, as it meets in Vienna, Austria, for its sixtieth session. In a statement to the commission, UNAIDS warns of the staggering rise in HIV infections among people who inject drugs and notes that countries are failing to invest in and deliver effective strategies to address the growing problem.

HIV infection among people who inject drugs is a major global issue. Between 2011 and 2014, there was a 33% rise in new HIV infections among people who inject drugs. Around 14% of the 12 million people who inject drugs worldwide, 1.6 million people, are now living with HIV.

UNAIDS estimates that people who inject drugs are up to 24 times more likely to be living with HIV than people in the general population. Despite this, people who inject drugs are often subjected to exclusion and marginalization and are left out of reach of services that prioritize health and human rights.

The good news is that there are simple, cost-effective programmes that work. Methadone maintenance therapy, for example, has been associated with a 54% reduction in the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs, yet many countries remain reluctant to implement proven approaches. Only about 50% of countries reporting injecting drug use implement effective harm reduction programmes.

Studies have shown that if countries were to make maintenance therapy available, 130 000 new HIV infections outside of sub-Saharan Africa could be prevented every year—this would result in a huge leap forwards towards ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030.

There are also serious shortcomings in funding, with most funding for harm reduction programmes, particularly in low-income countries, coming from international sources. Between 2010 and 2014, only 3.3% of HIV prevention funds went to programmes for people who inject drugs. To reach this key population with effective programmes to prevent HIV infection, UNAIDS estimates that annual investment in HIV prevention for people who inject drugs in low- and middle-income countries, will need to increase more than tenfold to US$ 1.5 billion by 2020.

It is clear that change needs to happen to get results. In 2016, United Nations Member States adopted a Political Declaration on Ending AIDS in which they committed to ensuring that 90% of key populations, including people who inject drugs, have access to HIV combination prevention services.

Providing a comprehensive package of services, including needle–syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy, in a legal and policy environment that enables access to services will be essential to prevent HIV infections and reduce deaths from AIDS-related illnesses, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections. UNAIDS is working closely with countries to help reach these important time-bound targets.

Quotes

“To end the AIDS epidemic and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals we need approaches that put people at the centre and ensure access to health and community-based services for all.”

Multimedia

Speeches

Related

Feature Story

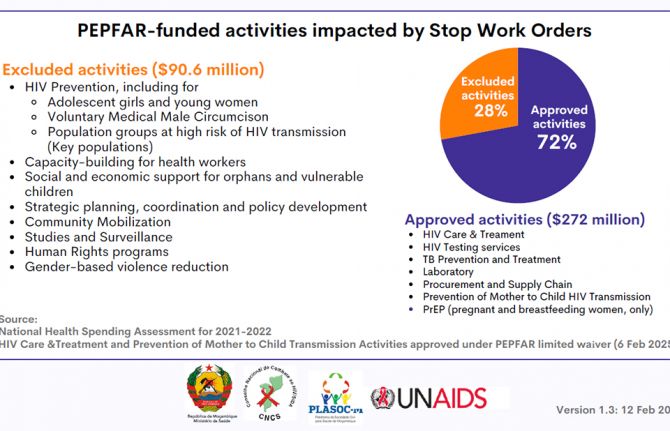

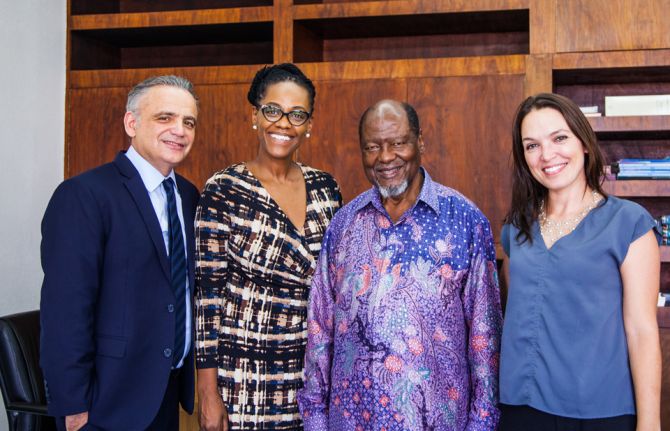

Mozambique: stepping up to Fast-Track its AIDS response

07 March 2017

07 March 2017 07 March 2017During a visit to Mozambique on 6 and 7 March, UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director Luiz Loures applauded the country’s efforts to Fast-Track its AIDS response. His visit took place at a critical moment for Mozambique, which is determined to accelerate its response to HIV with the support of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, whose representatives Mr Loures met.

Mozambique is among the countries most affected by the AIDS epidemic. HIV prevalence among adults was estimated to be 10.6% in 2015, with approximately 1.5 million people living with HIV. Nonetheless, and despite the challenges the country faces, Mozambique stands out as an example of how progress can be achieved through political commitment and international support. The coverage of antiretroviral therapy and HIV testing and counselling has increased considerably during the past years. By mid-2016, approximately 892 000 people living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral treatment, compared with around 308 000 people in 2012. New HIV infections among adults have been reduced, by 40% from 2004 to 2014.

In a meeting with the Minister of Health, Nazira Karimo Vali Abdula, Mr Loures congratulated the government for its significant progress. He recognized that while challenges remain, the country’s experience constitutes a showcase for the world of how to respond to the AIDS epidemic. The minister underlined the relevance of UNAIDS as a key coordinating platform for the international community and praised its global strategic leadership.

An important meeting during the trip was with the Mozambican Civil Society Platform for Health (PLASOC-M), which warmly welcomed him to the civil society meeting, held weekly at the UNAIDS country office. PLASOC-M unites local organizations helping to ensure close linkages between the national health system and the grass roots. After a productive exchange, Mr Loures pledged to back their efforts and to advocate on their behalf. He underlined the particular importance civil society has for populations that are hard to reach and often left behind, such as adolescent girls, sex workers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people, migrants, injecting drug users and prisoners.

The former President of Mozambique and Vice-Chairman of the Champions for an AIDS-Free Generation in Africa, Joaquim Alberto Chissano, received Mr Loures at his foundation’s headquarters. In the discussion between them, the need to revitalize primary HIV prevention, especially among youth, and the need to strengthen coordination and collaboration among lusophone countries in the HIV response, were highlighted.

Mr Chissano also highlighted the important role of private companies in the revitalization of HIV prevention, especially among youth, and pledged his continued support to this important issue.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Let’s go

07 March 2017

07 March 2017 07 March 2017The first thing you notice about Colonel Alain Azondékon is that he is always moving. He is tall, head and shoulders above most people, and he uses his whole body to express his feelings. So it will come as no surprise to learn that he ends every sentence with, “Let’s go!”.

The Director of Camp Guezo, the paediatric HIV hospital in Cotonou, Benin, the Colonel has started a new movement for putting young people and families at the centre of care.

After observing traditional check-up visits, he noticed that the children were separated from their mothers by a curtain during the examination. He rearranged the furniture, making sure that the examination table was parallel to where the parents were sitting, so they could always be in eye contact with their little ones and with the doctors and nurses.

That was just the beginning. He noticed that the young people under his care needed more than medicines to lead healthy lives. He introduced psychosocial support to address the stress of living with HIV through adolescence and created a network of young people living with HIV, run by a young man who is also living with HIV.

Talking with the Colonel you get the sense that he has tried to think of everything. “A mother never comes alone,” he pointed out. “She has her children, sometimes the father comes and she has her handbag, which contains her “life”.”

The Colonel made sure that instead of chairs in the examination and therapy session rooms there were small sofas—enough places for the family as well as the mother and her handbag.

It’s the small details, as well as the big mandate, that have made Camp Guezo so successful. Children born with HIV have received care from birth. The paediatric hospital has been able to reduce mortality rates among children living with HIV from 30% to less than 5%.

Some of the patients are now adults with children of their own and have very little interest in moving to the regular health-care system.

“They sometimes call me Papa, and they ask why Papa do we have to go to the other clinic where they don’t know me,” he said.

Soon patients of Camp Guezo could find it easier to transition to other health-care facilities. The Colonel has been asked to help replicate this model in other clinics in Benin.

“This is the kind of people-centred approach Africa and the world is looking for,” said Michel Sidibé, the Executive Director of UNAIDS, as he toured the centre. “Precious resources have been carefully put to work to keep families in a safe environment where they can get the care and support they need.”

There are an estimated 69 000 people living with HIV in Benin. The number of new HIV infections among children continues to fall as pregnant women living with HIV gain access to life-saving antiretroviral medicines to stop babies from becoming infected during childbirth and breastfeeding.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Ponce de Leon Center: a people-centred approach in the heart of the United States HIV epidemic

10 February 2017

10 February 2017 10 February 2017Each year, more than 6000 people are served by the Ponce de Leon Center in Atlanta, United States of America. For the past three decades the clinic has provided HIV care and services to men, women, adolescents and children living with HIV. Part of the Grady Health System, the Ponce Center is staffed by doctors and researchers from the leading research university in Atlanta, Emory University, and is considered one of the largest and most comprehensive HIV outpatient clinics in the country.

“The Ponce Center delivers comprehensive services to a vulnerable population in the heart of the United States HIV epidemic,” said Carlos del Rio, Professor of Global Health and Medicine and Co-Director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Atlanta’s epidemic largely affects the most vulnerable populations, who not only live with HIV but also live in poverty and are un- or underinsured. Many of the people who come to the centre for care are already very sick, having lived with HIV for a number of years undiagnosed and untreated. Thirty-five years into the epidemic, persistent stigma still keeps many patients from accessing life-saving treatment.

In 2015, owing to late stage diagnosis and treatment of HIV, some 50% of people diagnosed at the clinic already had AIDS. More than 75% of patients at the centre have advanced, symptomatic HIV disease (less than 200 CD4 cells/mm3 and/or AIDS-defining symptomatology).

In addition to breaking down the barriers that keep people from accessing the clinic sooner for earlier diagnosis, the Ponce Center is focused on how to make it easier for people to continue life-long HIV treatment.

The clinic provides comprehensive co-located services ranging from financial counselling and nutrition to acute care and chemotherapy. Providers take an integrated approach for people who may face multiple issues, including substance use and mental health issues. One of the key components is helping patients find the right combination of medicines with the fewest side-effects.

“Social capital is about having someone who can support the patient through their diagnosis and treatment. The patients who have no one else in their corner really do struggle and that is where the personal approach at the Ponce Center comes in,” said Wendy Armstrong, Professor of Medicine at Emory University and Medical Director of the Grady Infectious Disease Center.

Helping people manage their HIV also means supporting patients as they stabilize their lives, which is why the centre encourages close ties between patients and staff. The personal attention helps to support the logistics of treatment and encourages people to keep their medical appointments. Many people who access the clinic have also volunteered to take part in research studies to improve care.

“I am grateful for the tireless work of the staff to provide people-centred care at the Ponce Centre,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “This best practice approach is saving lives.”

The Ponce Centre provides a unique service to the thousands of people living with HIV in Atlanta as well as important research data and information, helping the United States to advance global efforts to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Region/country

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025