Feature Story

Community members are driving the AIDS response in northern Myanmar

26 March 2020

26 March 2020 26 March 2020Saung Moon was 15 years old when he first injected drugs. “I went out with some people who were using heroin and they persuaded me to try,” he said, puffing on a traditional Myanmar cigarette while squatting around a small fire with his friends.

Mr Moon, now 20 years old, lives in Putao, a remote area at the northern tip of Myanmar. Small rural communities are scattered around the mountainous region, part of the foothills of the Himalayas. But this lush and pristine environment is home to a severe drug epidemic fuelled by the availability of cheap heroin in the region. Widespread injecting drug use is resulting in high rates of HIV and hepatitis B and C infection.

Mr Moon and his friends were huddled around the fire at one of the two Medical Action Myanmar (MAM) facilities in the Putao district. The clinic is a satellite centre of the national AIDS programme and provides services—including needle–syringe exchange, HIV counselling and testing, HIV treatment and care, primary health care, testing and treatment of sexually transmitted infections and family planning—to people who inject drugs. The clinic also refers heroin users to the local hospital for opioid substitution therapy, since only government facilities are currently allowed to distribute methadone in Myanmar.

Mr Moon and his friends feel at ease at the clinic. Some are there to return their used needles and syringes and get clean ones, others to test for HIV or access their HIV treatment. Whatever the reason, health-care workers at the clinic take the opportunity to talk to them and train some of them as peer educators.

“If peer pressure is one of the main causes for heroin use initiation, the same principle applies when it comes to advising about the dangers of injecting drugs and how to prevent HIV transmission,” said MAM’s Medical Director, Cho Myat Nwe.

Raising awareness among people who use drugs is the first step in responding to the drug-related HIV epidemic—there isn’t a more effective way than sharing information and life skills among peers. “At school, we only received a brief talk about drugs, but nothing on HIV,” said one of Mr Moon’s friends. “With the information and training we have received at the clinic we can talk to our friends and provide them with important information to prevent infection.”

Engaging people who use drugs is only half of the challenge. The other half is reducing the stigma and discrimination they encounter in their daily lives.

According to Mrs Cho, people who use drugs are not very popular in their communities. The villagers do not understand why nongovernmental organizations focus their activities on people who use drugs and not on the general population. MAM is therefore working in the communities, providing general health care and discussing drug use and HIV, explaining why services for people who use drugs will have a positive effect on the community as a whole.

Services difficult to access

For most people who use drugs in Putao, getting to the clinic is a problem. The remoteness of the villages—some of them are as far as seven days away from the nearest health facility by foot—the poor infrastructure and the lack of public transport makes accessing services very difficult, especially during the rainy season. This leads to relatively high levels of people on long-term treatment stopping their treatment, including HIV treatment and opioid substitution therapy. “The problem is always transportation to come to the clinic or to the health centre to access methadone,” said another of Mr Moon’s friends. “We don’t have the money or the means of transportation to go to the hospital every day.”

MAM has mobile clinic teams visiting other villages in the district. The clinics stay open at night to make access easier, conduct outreach sessions and provide information on harm reduction and HIV prevention where people who use drugs gather. That’s how Mr Moon and his friends got to know about the clinic and the health options available to them. However, the reach of the mobile clinic is limited.

Community health volunteers are making a difference

Community health volunteers, who provide a wide range of health services in the villages, have made a real difference to the ability of people to access services.

The volunteers were originally trained by MAM staff to test and treat malaria. People with fever would visit them. They would then perform a simple test and if positive for malaria they would provide treatment immediately. According to the health authorities, the volunteers were part of a successful effort that led to a decline in the malaria rate among those reporting fevers in Putao from 4.2% in 2015 to 0% in 2019.

Now trained twice a year, their services have grown beyond malaria testing and treatment to include counselling for HIV, needle–syringe exchange, tuberculosis referrals, sexual and reproductive health services and the referral of severely ill patients to government hospitals.

Despite their limitations, community health volunteers are bringing health services and information much closer to people and are reaching out to a population that would be otherwise very hard to reach. Their work is greatly contributing to the decentralization of services and is helping to unblock an overstretched health system.

While still insufficient to cover the needs of the community, the response to HIV in Putao links community health volunteers, a nongovernmental organization clinic and a township hospital providing antiretroviral therapy and opioid substitution therapy. As such, it is an example of a strategy that can be further expanded for wider coverage in nearby localities.

The predominantly rural nature of injecting drug use in the country poses challenges for how to effectively deliver harm reduction services. While Myanmar has unique examples of how to adapt programmes to local contexts, there is an urgent need to evaluate the public health outcomes and impact of such innovative and adapted responses in the coming months as the country gears up to further intensification of its AIDS response with support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief and Access to Health.

Resources

Region/country

Feature Story

Chains of solidarity and kindness during the COVID-19 outbreak

20 March 2020

20 March 2020 20 March 2020Getting calls at all hours of the day is not unusual for Liu Jie, the Community Mobilization Officer in the UNAIDS Country Office in China. Because of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, the whole office has been active in helping people living with HIV to continue to access treatment, especially in Hubei Province, where the pandemic was first reported. Recently, Ms Liu was surprised when she had a call from Poland.

"A Chinese man introduced himself, saying he is stranded and will run out of HIV medicine in two days,” Ms Liu said.

With travel restrictions closing down more and more countries, the man could neither return home nor access medicine. Not knowing what to do, he reached out to a Chinese community-based organization, the Birch Forest National Alliance, and through them contacted UNAIDS in Beijing, she explained.

He, like countless other people abroad, was caught in limbo by the fallout from the COVID-19 outbreak. Days earlier, the UNAIDS Country Office in China had helped another Chinese person living with HIV access medicine while stuck in Angola. In both cases, colleagues in Beijing reached out to UNAIDS country offices and the Community Mobilization Team in Geneva, Switzerland. The UNAIDS Country Director for Angola reached out to the Angolan Network of AIDS Service Organisations and the person accessed medicine in no time.

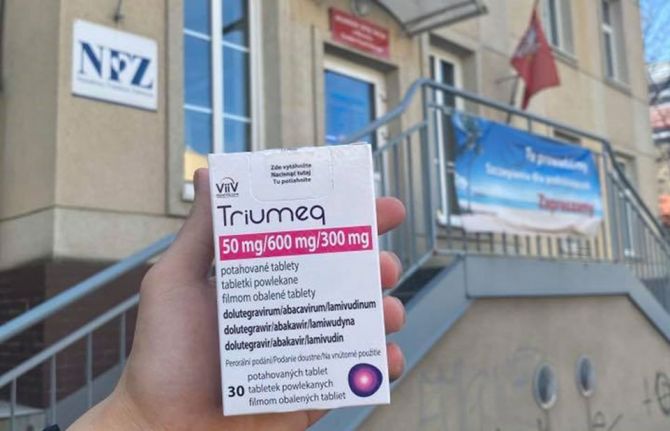

For the case in Poland, Jacek Tyszko, a Polish native and part of the UNAIDS Community Mobilization Team, knew exactly what to do. “Because we have been in touch with regional networks of people living with HIV in central and eastern Europe, I made one call,” Mr Tyszko said.

Anna Marzec-Boguslawska, head of the National AIDS Center in Poland, quickly agreed to follow up. She has always been very responsive, which allows us to move quickly on the ground. Twenty-four hours later, Ms Liu received a photo of a man holding up a box of medicine in front of a grey building. Minutes later her phone rang.

“It was the same Chinese guy calling again from Poland,” she said. “He was crying with joy, saying he had his medicine and that was a picture of him just now.”

She added, “He kept saying how he could not believe that we made the impossible possible.”

The Director of the Birch Forest National Alliance, Bai Hua, also thanked UNAIDS. “This case really reflects that UNAIDS is rooted among the communities,” he said.

Resources

Feature Story

The volunteer driver in Wuhan

24 March 2020

24 March 2020 24 March 2020On the day of China’s Lantern Festival, 8 February, Shen Ming was making sweet dumplings, the traditional festival delicacy, at his home in Wuhan in China’s Hubei Province. From time to time, he would raise his head to watch the local news on the television to get the latest on the COVID-19 outbreak.

His paid particular attention to the new traffic restriction measures. Unlike most people in the city, who stayed indoors all day because of the lockdown, Shen Ming needed to go out almost every day—he is a volunteer who is driving people living with HIV to pick up their medicines from hospitals during the outbreak.

Shen Ming had planned to drive someone to Jinyintan Hospital in the afternoon. Just enough time to have the sweet dumplings, he thought. As the water began to boil, his phone rang. A colleague from the Wuhan Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Center asked him if he could drive another two people to get their medicine right away. He said yes. “You see,” he said. “It will save me a lot of time because I can drive three people to the hospital in one go.”

He switched off the hob and put on a protective suit and mask. “Never mind the sweet dumplings. I can cook them later,” he said. “Besides, I can have a video call with my parents while I’m having the dumplings in the evening.”

A new year away from home

It was more than two weeks since Wuhan, the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak, was locked down. An uncomfortable silence hung over the city, which appeared deserted, in stark contrast to the energy of the city before the outbreak.

Shen Ming had had totally different new year plans. He had booked a flight to his home town in Zhejiang Province and had even bought some spicy local delicacies for his parents as new year gifts. “They are more accustomed to sweet food, but I want them to try something different,” he said.

Two days before his flight, Shen Ming got a text message from his boyfriend. “How are you?” the message read. “I got bad news: my father has been diagnosed with COVID-19. And my mother and I both have a high fever too. We are all on the way to the hospital and will stay there if there are beds for us.”

Shen Ming offered his condolescences to his boyfriend, and the next day went to see his doctor. He was relieved to be told that he was not infected, but was advised to stay in Wuhan for observation—he never thought that the coronavirus would be the reason for his first new year away from his family.

So, you are also HIV-positive, like us?

His first passenger was from Shanghai. Wuhan was put under lockdown just as he was about to leave. Soon, he found his HIV medicine running out. “If the medicine of people living with HIV is disrupted, their health will suffer. It might be inaccurate, but I can feel their fear, anxiety and dispair,” Shen Ming said.

Thanks to a directive from China’s National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, people living with HIV can receive medicine refills wherever they are. All they need is a letter from their service provider. However, they faced a challenge, as taxis and public transport services were stopped during the lockdown.

A survey jointly conducted by UNAIDS and the BaiHuaLin alliance of people living with HIV, a community-based organization in Beijing, shows that nearly 65% of the respondents in Hubei Province had difficulty getting their medicines during the lockdown. With most medical staff concentrating on COVID-19, community-based organization such as the Wuhan Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Center asked for volunteers like Shen Ming to transport people living with HIV to pick up their medicines.

On his first drive, Shen Ming put on three face masks and rolled down the car window to reduce the possibility of getting infected. His trip was to the same hospital that looked after people affected by COVID-19. He was nervous when arriving at the hospital, but to his relief the HIV clinic and the COVID-19 clinic were far apart. The Wuhan Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Center gave him a protective suit after learning that he didn’t have adequate protective equipment, and he eventually became more relaxed.

He would walk to the clinic with his passengers and wait there until they got their medicine. Afterwards, they would have a chat. “So, you are also HIV-positive, like us?” almost all of them would ask Shen Ming. He isn’t. “It doesn’t matter,” he said. “AIDS is just a chronic disease. The care for people living with HIV goes beyond the community of people living with HIV.”

“I will probably stay here”

It was late when he got back home after driving the three people to the hospital on the day of the Lantern Festival. Hungry, he turned on the hob and cooked noodles. This is the first time that Shen Ming hadn’t had sweet dumplings on the Lantern Festival, but he was happy because he got to meet his boyfriend, albeit briefly.

“I will continue my volunteering work until they don’t need me. It would be best if I’m not needed,” he said with a smile on his face.“I will probably stay in this city. I’ll buy a house when the epidemic is over, and build a home here.”

Resources

Region/country

Feature Story

Mining, drugs and conflict are stretching the AIDS response in northern Myanmar

23 March 2020

23 March 2020 23 March 2020“People who inject drugs can access harm reduction services and HIV treatment, but they still don’t go for them. Why?” asked Deputy Director-General of Communicable Diseases of the Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports, Thandar Lwin, while searching for ways to respond to the drug-related HIV epidemic in northern Myanmar.

One of the most affected regions is the northern most state of Kachin, where, according to government statistics, 72% of new HIV infections occur among people who inject drugs.

Bordering China on the east and India on the west, Kachin State reports the highest prevalence of HIV in the country, at 2.8%—the national HIV prevalence is estimated at 0.57%. The state is home to only 3% of the country’s population, but to 23% of all the people who inject drugs in Myanmar, whose HIV prevalence is more than 40%.

The reasons for such a concentrated epidemic among people who use drugs are varied. Mining, particularly for jade, illicit drug cultivation, production and trafficking, limited education and access to health services, and armed conflict are some of the obstacles to an effective response to the epidemic in the area.

Heroin and methamphetamine are widely available in towns and rural areas. The drugs are used by those who work long hours in mines and plantations, or for recreational purposes by children as young as 14 years, who can inject several times a day.

In response, the government is providing HIV and harm reduction services at its health facilities and through a network of satellite clinics and drop-in centres run by nongovernmental organizations working with community health volunteers. Together, they provide, or refer people to, a wide range of services, including peer counselling, testing and treatment, needle–syringe programmes, opioid substitution therapy, condoms and treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

However, even with a government willing to support harm reduction services, the magnitude of the drug use problem is stretching capacity. Although there is political will, and financial resources are available, there is an urgent need to better understand the reasons why services are not always reaching the people who need them the most.

For that reason, a delegation led by the Government of Myanmar and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund)—the biggest funder of the AIDS response in the country—together with the technical partners, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization, and the principal recipients, the United Nations Office for Project Services and Save the Children, visited the area to see how programmes are being implemented and to find alternative ways to effectively deliver services.

“Programming in this context requires partnership, collaboration and innovative approaches to ensure that the investments and activities have an impact in such a demanding environment,” said Izaskun Gaviria, Senior Fund Portfolio Manager at the Global Fund.

The visit showed that a good multipartner national response to HIV is producing results in parts of the country, but is falling short in areas affected by poverty and because of the availability of cheap drugs, a mobile population following seasonal work and long-standing ethnic conflicts. It also showed that policy changes are urgently required in order to improve access to opioid substitution therapy, antiretroviral therapy and other health services, including needles and syringes and naloxone for overdose management.

Fifty-nine per cent of people who use drugs in Myanmar were tested for HIV in 2016, rising to 74% in 2018. However, there is a gap between the number of people who test positive for HIV and the number of people who start on antiretroviral therapy. Many of the people either not initiating treatment or stopping are mobile seasonal workers, who come from within and beyond Kachin State.

The need for confirmatory HIV tests to be made at public health centres and the fact that people must have several mandatory counselling sessions before treatment can be initiated may also be contributing to the high percentage of people who test positive but are not yet accessing treatment. The Ministry of Health and Sports has issued a directive stating that all designated public sector services can initiate antiretroviral therapy. However, more reforms are required to bring health care to people who use drugs, who face legal challenges and, often, hostility in local communities.

The government has for a long time demonstrated a genuine interest in providing harm reduction services to people who inject drugs. Sterile needles and syringes can be obtained from health services run by nongovernmental organizations and rural drop-in centres, and some villages even have needle–syringe dispensers. However, the two syringes per user per day falls short of the actual daily injection average, and the needles and syringes are not distributed proportionally where the people who inject drugs live.

Furthermore, the fact that only public health facilities are authorized to provide opioid substitution therapy is hindering efforts to reach out to the people who need it. Transportation costs and remoteness are other obstacles to people who use drugs accessing their daily dose of methadone. Even the take-home dose, which the government is piloting among qualifying users, requires people to travel long distances to access it.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, however, remains the stigma and discrimination faced by people who use drugs and the resistance to harm reduction, especially needle–syringe programmes, at the local level from law enforcement agencies and faith-based antinarcotic drug groups in Kachin State. A lack of understanding of the concept of harm reduction, including the mistaken belief that the distribution of needles and syringes encourages drug use, is at the root of the stigma and discrimination. Police crackdowns and anti-drug operations by faith-based organizations contribute to driving people who inject drugs underground, away from harm reduction services.

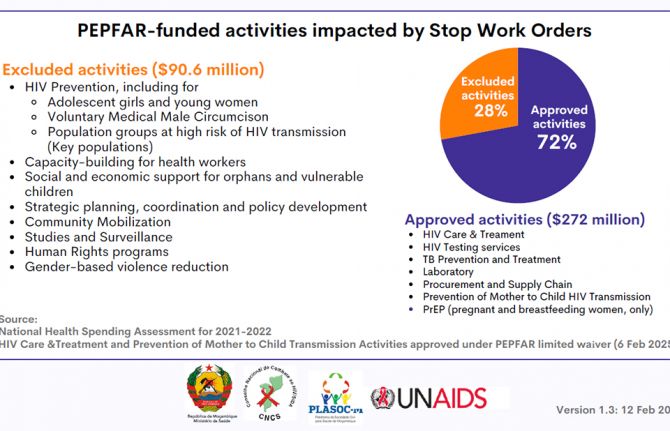

The visit also brought to light an increasing hepatitis C epidemic among people who inject drugs. Testing for hepatitis C has revealed an estimated prevalence as high as 80% in at least one township among people who inject drugs. But despite this staggering percentage, there is currently no widescale hepatitis C treatment available. This, however, is something that the Global Fund is now considering to include in the next grant cycle following discussions with health officials and partners, together with an improved needle–syringe programme, the use of buprenorphine as an alternative to methadone and the introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis. The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief is also contributing to funds for some of these innovations. But perhaps one of the most urgent improvements required is the creation of a unique code identifier, with sufficient safeguards for confidentiality, in order to provide patients with the treatment and services they need no matter where they are in the country.

Overall, and despite the many challenges, Myanmar is showing steady progress in its response to HIV thanks to a well-coordinated multipartner response. An extensive investment of resources by the Global Fund and other donors, as well as an increase in domestic funding, has led to a substantial scale-up of services across the country, which has resulted, according to the government, in the number of new HIV infections dropping by 31% from 2010 to 2018. Eighty per cent of people living with HIV in Myanmar know their status and the percentage of people living with HIV who have access to antiretroviral therapy rose from 1% in 2005 to 70% in 2018.

Nonetheless, the capacity of the government and nongovernmental organizations to deliver services seems to be reaching its limits. According to the UNAIDS Country Director, Oussama Tawil, “Key elements to expand the provision of services would include allowing task-shifting towards primary health-care providers, community health volunteers and the wider local community, improving linkages and integration of public and nongovernmental organization services and investing in human resources.”

The situation in Kachin State as well as other neighbouring states with similar characteristics, such as Shan North and Sagaing, has shown that there is an urgent need to adapt the AIDS response to specific locations and populations, but also that socioeconomic contexts have to be addressed for public health approaches to succeed. “Unless we address the underlying family livelihood issues and wider health consequences, and adapt to the local realities related to mining, economic interests and drug use, existing services won’t be enough,” said Mr Tawil.

Region/country

Feature Story

Norway’s community organizations ensuring health, dignity and rights

17 March 2020

17 March 2020 17 March 2020It was a very different morning bus ride for UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima as she boarded the hepatitis bus in Oslo, Norway, to hear more about the work of ProLAR, an organization that supports people who use drugs. ProLAR provides a range of services, including opioid substitution therapy and testing for HIV and hepatitis C. It is also active in calling for changes in drug policy and promotes evidence-informed policy that involves the affected communities.

“We welcome people who use drugs into a warm, safe space. Here we can talk, get to know each other then take the necessary tests,” explained Ronny Bjørnestad, Managing Director of ProLAR.

According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, around 9000 people who inject drugs lived in Norway in 2019, many in the two largest cities, Oslo and Bergen. In 2015, the Norwegian Government presented a new action plan addressing substance use and addictions that prioritizes prevention, early intervention, treatment and aftercare for people who use drugs. In 2018 the European Centres for Disease Control reported that there were only six new diagnosis of HIV among people who inject drugs in Norway.

Ms Byanyima also visited Sjekkpunkt, a free and anonymous testing service in Oslo for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections that caters for gay men and other men who have sex with men. Rolf Martin Angeltvedt, Director of Helseutvalget, said that, “Checkpoint does not say “no” to anyone who wants to come in to talk and take a test. We offer free, anonymous and rapid testing.”

New HIV infections among gay men and other men who have sex with men have been declining steadily in Norway in recent years. In Norway the most commonly reported mode of HIV transmission in 2018 was heterosexual transmission.

Following the visit to Sjekkpunkt, Ms Byanyima met with representatives of civil society organizations working in Norway on issues concerning people living with and affected by HIV. The dialogues centred around sex work, chemsex, ageing, youth, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and and intersex people and migration. In Norway, civil society groups play a critical role in addressing the AIDS epidemic by supporting prevention, treatment and care efforts.

“The leadership of networks and peer-led organizations working to support people living with, and affected by, HIV is instrumental. More than ever, the role of civil society is critical to removing barriers to health, dignity and the enjoyment of human rights. I encourage you to build bridges with civil society organization in other regions of the world. We must work together to reverse the disturbing trend of shrinking space and lack of funding for civil society or we will fail to reach the target of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030,” said Ms Byanyima.

Region/country

Feature Story

UNAIDS—a leading organization for gender equality

13 March 2020

13 March 2020 13 March 2020A report on the progress made over the past 12 months by organizations active in the health sector to implement policies that promote gender equality, non-discrimination and inclusion in the workplace has once again rated UNAIDS as a “very high scoring” organization.

UNAIDS is one of only 13 out of the top 200 global health bodies—funders, nongovernmental organizations, corporate organizations and others with a presence in at least three countries—to be designated as very high scoring. A further 27 organizations were “high scorers”.

“I’m proud that UNAIDS is seen as gender-responsive and inclusive,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “But we must continue to build on these results—we’ve still got a long way to go.”

Researchers assessed the gender and geography of global health leadership, and the availability of gender and diversity policies in the workplace. The report also assessed whether organizations address the crucial role of gender in their health investment programmes and the health priorities they address.

While identifying some progress towards gender equality across the 200 organizations surveyed, the report warns that the pace of change is too slow, estimating that it will take more than 50 years to reach parity at the senior levels of global health organizations.

“Many of the 200 organizations we reviewed are falling short on the equality measures that they purport to uphold. More than 70% of the chief executives and chairs of boards are men, while only 5% are women from low- and middle-income countries,” said Sarah Hawkes, co-founder of Global Health 50/50 and Professor of Global Public Health at University College London.

Power, privilege and priorities is the third Global Health 50/50 report. Previous Global Health 50/50 reports have also found UNAIDS to be a gender leader, being rated in the top nine out of 140 organizations in 2018 and in the top 14 out of almost 200 organizations in 2019.

Feature Story

Getting HIV services to marginalized groups in Papua New Guinea

11 March 2020

11 March 2020 11 March 2020There are around 45 000 people living with HIV in Papua New Guinea, with marginalized groups, such as sex workers and other women who exchange sex for money, goods and protection, gay men and other men who have sex with men and transgender women, most affected. However, less than half of the people who belong to those vulnerable groups have ever taken a test to know their HIV status.

In November 2018, UNAIDS, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other partners implemented a new outreach programme in the capital, Port Moresby, to try to reduce the impact of HIV among those groups of people by mapping the HIV epidemic and expanding HIV treatment and prevention services. Under the project, several outreach teams were created to promote and increase the uptake of testing and prevention services and to link people to HIV prevention and care services, if necessary.

By April 2019, the outreach teams had contacted 5000 people and tested 3000 of them for HIV, offering advice and support so that each person understood their test result.

“I like that we go to new places where people have never been offered an HIV test,” said a member of one of the outreach teams. “My motivation is meeting the young girls and taking care of them—making sure they take their medication.”

The outreach workers sometimes face harassment while conducting their work and change out of their official uniforms and into their own clothes so that people feel more comfortable talking to them. But the outreach workers find the work deeply rewarding.

“I have lost friends to AIDS, so that keeps me doing this work,” said another of the outreach workers. “It makes me work extra hard not to see someone else lost to this disease.”

The outreach teams are led by members of marginalized groups, an essential part of establishing community trust and engagement. In addition, leaders offer coaching, support and advice to field workers on a daily basis in order to ensure that their activities are as effective as possible.

The outreach programme is saving lives. Another of the outreach workers recalled his work with a transgender person, who he persuaded to try medication after testing positive for HIV.

“He told me that because he is transgender, he will only talk to a friend and that when he saw me, he knew I was a friend. Later, he brought in his companion to take a test.”

“This is a model of what can be achieved when we put our trust in community-led HIV services and programmes,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director, in discussion with the outreach workers during her visit to Papua New Guinea with the United Nations Deputy Secretary-General, Amina Mohammed. “These outreach workers are heroes and they are saving lives.”

The outreach programme is also cost-effective and is projected to save hundreds of thousands of dollars over the next two years.

Region/country

Feature Story

Mozambique: helping people living with HIV to get back on treatment

11 March 2020

11 March 2020 11 March 2020Photos: UNAIDS/P.Caton

It’s been a year since Cyclone Idai made landfall in Sofala Province, Mozambique, where one in six of the population is living with HIV. The cyclone caused devastating floods that destroyed homes and washed away savings, documentation and medicines. Thousands of people were displaced. Health centres across the province were destroyed or severely damaged.

Working with national and provincial authorities, including Mozambique’s Ministry of Health, UNAIDS responded by helping to re-establish community-based support programmes to find thousands of people who had been lost from HIV treatment in order to ensure that they received the necessary support to get back and remain on treatment.

Community volunteers and HIV activists received bicycles from UNAIDS to help them reach people affected by the flooding and to locate people lost from treatment programmes.

Community activists fanned out across areas affected by the disaster.

When the cyclone hit, 14-year-old Pedro José Henriques lost everything, including his medication and his identity card. Community activists supported by UNAIDS helped him receive a new identity card so that he could re-register at the health clinic and obtain new antiretroviral medicines.

“I was so happy to get my new medicines,” he said. “When the activists found us, we had nothing. At least now my grandmother and I have somewhere to stay. It’s not much, but it’s better than sleeping in the cold.”

Rita Manuel is disabled and living with HIV. Her husband is also HIV-positive. When they lost both their children to AIDS-related illnesses, they decided to stop taking their HIV medicines. They simply lost the will to live.

After the cyclone, activists in the lost-to-follow-up programme visited the couple three times. Finally, Ms Manuel and her husband agreed to visit the health centre and resume their medication.

The activists belong to an association called Kupulumussana, which means “we support each other”.

Ms Manuel is now involved in some of the association’s activities herself. “I am not really happy because I wish I had known about this treatment for my children,” she said, “But I am grateful to be alive and to have people supporting me. The situation is better than before.”

Peter Joque is also in an association to help people affected by the disaster. The Kuphedzana association helped Mr Joque rebuild his home after the cyclone and helped him get back on his feet.

This motivated him to start helping to find people in need of HIV medication. He uses hospital records to search for those who were displaced.

When he finds someone, he takes time to talk to them about the importance of staying on treatment. Mr Joque’s door-to-door strategy managed to locate 40 people living with HIV and persuade them back on to antiretroviral therapy.

“Talking to someone face to face means it is easier to persuade the person to return to the health centre,” he said. “Stigma and discrimination is still a challenge among communities.”

Medical staff like Alfredo Cunha at the Macurungo health facility treat all patients with respect and dignity. Everyone receives the best care possible.

Sowena Lomba lost her husband to an AIDS-related illness in 2014. When she started getting ill, she thought she had malaria, but when she tested for HIV the result came back positive. During the flooding she lost her identity card and was no longer able to receive treatment. Activists helped her to receive new documents and get back on to treatment.

Ms Lomba says she is grateful to be alive for the sake of her children, Evalina and Mario.

Community activists have now helped more than 20 000 people back on to treatment over the past 12 months and say they won’t stop until they have found everybody lost to treatment, including those who were in need before the catastrophic events of March 2019.

“We are still at it and we will not stop until everybody living with HIV is receiving treatment and care,” said one of the activists.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

HIV data check in Papua New Guinea’s National Capital District

06 March 2020

06 March 2020 06 March 2020For six weeks, two teams covered 12 HIV clinics on a data checking mission in Papua New Guinea. UNAIDS joined the country’s strategic information technical working group in the National Capital District, which includes Port Moresby, to inspect the clinics’ records to see if they match the records of the National Department of Health.

“The data quality assessment is part of the country’s HIV monitoring and evaluation plan to ensure the quality of data and reporting of the AIDS response,” explained Zimmbodilion Mosende, UNAIDS Papua New Guinea Strategic Information Adviser.

Led by USAID, the two teams of 12 branched out into smaller teams to look at the number of people registered as enrolled on antiretroviral therapy, the number of people newly starting treatment, the percentage of people returning for refills and the number of people who did not return to the clinics. In addition, the groups checked information on, for example, the age and sex of each person.

The volunteers from civil society groups, international nongovernmental organizations, development partners and key government offices went through the records of nearly 5000 people.

Papua New Guinea has the highest HIV incidence and prevalence in the Pacific region. The country of 8.4 million people represents 95% of the reported HIV cases in the region. There are approximately 45 000 people living with HIV in the country, of whom 65% are on antiretroviral therapy.

The groups tried to find out if there are discrepancies in the data and the reasons behind them. Albert Arija, Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist of USAID, described the reasons for discrepancies, which range from there being an inadequate number of staff, hence not enough time to fill out all entries, to incorrect data entry or at times misinterpretation of information. For fear of stigma and discrimination, some clients don’t want to give personal information.

One key missing data point was also birthdates. “Many people in Papua New Guinea cannot recall their exact date of birth,” said Mr Arija.

The technical working group is advocating for the use of electronic forms and real-time reporting. “Since the current antiretroviral therapy forms are still paper-based, there are several potential data quality risks, including human errors, from the data entry and processing,” Mr Mosende said.

Overall, most of the clinics had good quality data and processing, according to the teams’ assessment. They hope to simplify the overall process to scale up the data check for the whole country.

Related information

Region/country

Feature Story

Raising the voices of women at the forefront of climate change

05 March 2020

05 March 2020 05 March 2020The Pacific region has among the world’s highest rates of gender-based violence. National research show that 72% of Fijian women experience gender-based violence, compared to the global average of 35%. Women in the region also have a low representation in leadership positions—out of the 560 Pacific members of parliament, 48 are women, of whom 10 are Fijian women.

Adding to these sociocultural impacts is the climate emergency. In response, Pacific women are demanding more involvement in climate-related decision-making and to be fully engaged in climate responses.

Komal Narayan, a Fijian climate justice activist, became fascinated during her postgraduate programme in development studies about how climate change overlapped with ethics and politics. “The effects of climate change are felt most acutely by the people who are least responsible for causing the problem,” she said. This motivated her to be more active and vocal about the issue, leading to her participation, together with other young delegates from Fiji, in the twenty-third United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Bonn, Germany, in 2017.

“My goal in life is to be part of a society that is focused on addressing the issues of climate justice and encouraging and motivating more young people to be more involved in this space, as I believe that this issue is not just yours or mine but an issue that is at heart for the entire Pacific,” Ms Narayan said.

Ms Narayan was also one of the Green Ticket Recipients for the United Nations Youth Climate Action Summit in September 2019, where she was involved in a youth-led dialogue with the United Nations Secretary-General.

“As givers of life, as dedicated mothers, thoughtful sisters, domestic influencers and active contributors to socioeconomic development, we women have the power to give impetus to the global climate movement,” Ms Narayan said. “It’s about time that women and girls are given equal opportunities and equal access to resources and technology to be able to address climate justice. Countries, specifically government and civil society, should be playing a key role in this.”

AnnMary Raduva, a year 11 student at Saint Joseph’s Secondary School in Suva, Fiji, believes that climate justice must recognize the connection between humans and the environment and how vulnerable we are if we don’t do something today.

“In the Pacific region, our indigenous communities depend intimately on the ecological richness for subsistence, as well as economically, and this dependence makes our people sensitive to the effects of extreme weather events, and we cannot ignore them. We have a close relationship with our surroundings and are deeply spiritual and culturally connected to the environment, and ocean, and this relationship has positioned us to anticipate, prepare for and respond to the impacts of climate change,” Ms Raduva said.

In 2018 she wrote to the Fijian Prime Minister asking him to relook at the Fiji Litter Act 2008 to classify balloon releasing as littering in Fiji. Ms Raduva soon realized that talking about balloon releasing was not enough, however, and that she had to find eco-friendly alternatives to amplify her message. The idea of planting mangroves along the Suva foreshore soon came to her.

Since 2018, she has initiated six planting activities and has planted more than 18 000 mangrove seedlings. She was invited to New York, United States of America, in September 2019 to march for climate justice at a United for Climate Justice event organized by the Foundation for European Progressive Studies. She stood in solidarity with the indigenous communities that are on the forefront of climate change as it advances in the Pacific region.

Ms Raduva has faced discrimination as a young female activist and has been mocked as a “young, naive girl”. She was told that she must not talk about climate change because activism is reserved for boys and adults. However, she believes that ensuring the participation of women, children and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people and other minority groups in climate change talks is a priority for any institution or organization that aims to champion climate change issues.

Varanisese Maisamoa is a survivor of Cyclone Winston, which in 2016 was one of Fiji’s most powerful natural disasters. In 2017, she formed the Rakiraki Market Vendors Association, working with UN Women’s Markets for Change project—“We want to empower our market vendors to be climate-resilient,” she said. Through UN Women’s leadership training, she learned to be confident when speaking out about the issues affecting market vendors and to negotiate with the market council management.

Ms Maisamoa represented her association on the design of the reconstruction of Rakiraki’s market, which now features infrastructure resilient to a category 5 cyclone, a rainwater harvesting system, flood-resistant drainage and a gender-responsive design.

Ms Narayan, Ms Raduva and Ms Maisamoa are among the Pacific women who are pushing for more of a voice in and inclusiveness for women and girls in climate action. Their activism is working to reduce discrimination against women and girls, which results in inequalities that make them more likely to be exposed to disaster-induced risks and losses to their livelihood, and to build resilience for women to adapt to changes in the climate.

Ms Maisamoa’s story has been republished with permission from UN Women’s Markets for Change project, which is a multicountry initiative towards safe, inclusive and non-discriminatory marketplaces in rural and urban areas of Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu that promotes gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. Implemented by UN Women, Markets for Change is principally funded by the Government of Australia, and since 2018 the project partnership has expanded to include funding support from the Government of Canada. The United Nations Development Programme is a project partner.