Feature Story

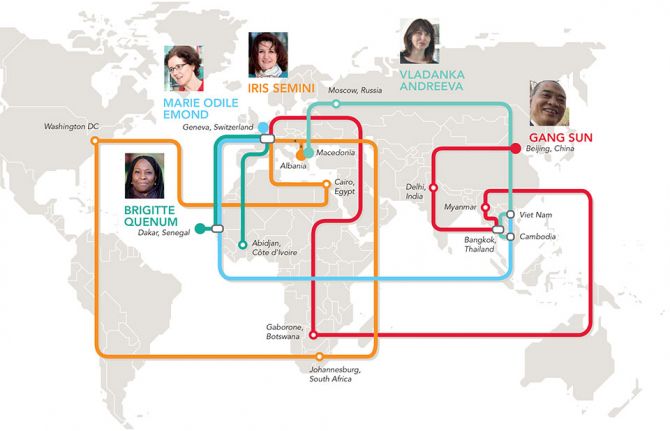

UNAIDS staff share global experience on AIDS through criss-crossing the world

19 March 2018

19 March 2018 19 March 2018When Marie-Odile Emond first arrived in Cambodia, she didn’t realize that some of the UNAIDS/International Labour Organization policy on HIV in the workplace she had heard discussed, years back, at the global level would be something she would see implemented.

“It seemed so abstract and yet here I was seeing it in practice,” she said, referring to health and human rights protection for workers, notably sex workers, which involved the Ministry of Labour, the community and the United Nations. “As the Country Director, I facilitated the dialogue and training for that to happen,” Ms Emond said, “and now it serves as an example for other countries.”

She now heads the Viet Nam Country Office, which she said offered another set of challenges and opportunities.

“I have found it really interesting to alternate between global, regional and country offices, because each offers a window to a part of our strategy,” Ms Emond said. Rattling off the many countries she has worked in at UNAIDS, she laughed and said, “Oh, and before UNAIDS, I worked in Armenia, Burundi, Liberia and Rwanda.”

In her opinion, meeting so many committed people from all walks of life and building bridges with them has been enriching. It’s made all the difference, according to her, in the AIDS response. “I play the coordinator, but I also had an active role in making people believe in themselves,” Ms Emond said.

Country Director Vladanka Andreeva said that her moves within UNAIDS were a huge change each time. She has served across two regions in different roles and credits her professional growth to her colleagues and the various communities she has interacted with.

“In every new post there was a challenge to quickly adapt to it, establish relationships with stakeholders and make a contribution,” she said. “You really have to hit the ground running.” Her role as the Treatment and Prevention Adviser in the UNAIDS regional office in Bangkok, Thailand, before going to Cambodia, really stands out for her. Ms Andreeva provided technical advice and assistance to strengthen HIV programmes across the region. This involved facilitating knowledge and sharing best practice, in and between countries, on innovative delivery models to scale up access to evidence-informed services.

She added that, from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to Cambodia, “my family and I explored the cultural heritage of our host countries, tasted some of the most delicious pho, tom yum and amok, and made friends from all over the world.”

She thanked her husband and daughter for being fantastic partners in the journey, since moving every four to five years is no small task. UNAIDS staff move routinely from one duty station to another, criss-crossing the world throughout their careers.

Her real pride is seeing her 17-year-old daughter, who was six when they started living abroad, become a truly global citizen, with such respect for diversity.

Gang Sun echoed many of Ms Andreeva’s points. “Because we interact with so many stakeholders, from the private sector to government to civil society, I have learned to always show respect and always listen,” he said.

For him, the journey started in the field in China, India and Thailand, followed by Myanmar and Botswana, before starting his new job at UNAIDS headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2017. He described that adapting to different cultures has kept him on his toes. “Overall, in my career I have seen every challenge as an opportunity and I have gained in confidence,” he said.

What fascinated him the most was the differences between working in high HIV prevalence countries and in countries where the epidemic was concentrated among key populations. In his new role at headquarters, he now taps into his expertise gained along the way as well as that of so many colleagues within UNAIDS and the World Health Organization.

“Despite all my experience, I still have more learning to do,” Mr Sun said.

The Côte d’Ivoire Country Director, Brigitte Quenum, jumped at the opportunity to go to the field after more than five years in Geneva. As the Partnerships Officer with francophone countries at UNAIDS headquarters, she said she learned a lot about how the UNAIDS Joint Programme functioned. That has helped her in her current role working hand in hand with Cosponsors, financial partners and civil society.

Before working in Geneva, she worked in the western and central Africa regional UNAIDS office in Dakar, Senegal. “I have gone full circle, and that has been very rewarding, because I know how the entire organization functions,” Ms Quenum said. Reflecting on the recent change in her life, aside from adjusting to the muggy coastal weather and the sheer population size of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire—the city has as many people as all of Switzerland—she said, “Being on the ground gives one’s job more of a sense of urgency, but I think it’s because we have daily contact with the multiple communities we’re serving.”

More in this series: It’s about the people we serve: UNAIDS staff connecting the world

Related

Feature Story

Human touch and targeted screening help to reduce HIV outbreak in Athens

16 March 2018

16 March 2018 16 March 2018Greece experienced a large increase in 2011 in the number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs. The number of new diagnoses in Athens usually hovered around 11 per year, but shot up to 266. For the first time, injecting drug use and sharing needles became the main source of new HIV infections in Greece, according to the Medical School of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

In response, the university, along with the Greek Organisation against Drugs and other nongovernmental organizations, launched a programme to “seek, test, treat and retain”, under the name Aristotle, in order to put a halt to the outbreak.

Their first challenge was finding people who inject drugs and identifying if they were HIV-positive.

“Many lived on the streets, some had been in prison and in many instances they were migrants with no knowledge of Greek,” said Vana Sypsa, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and a lead on Aristotle, along with Angelos Hatzakis, Meni Malliori and Dimitrios Paraskevis.

She explained that because of the economic recession, people lost their jobs and shared injecting equipment with other people, and homelessness crept up. In addition, she added, sterile syringes were hard to come by and opioid substitution therapy centres had long waiting lists. The Aristotle programme used a coupon system so that peers could recruit people to come in for an HIV test in return for a stipend.

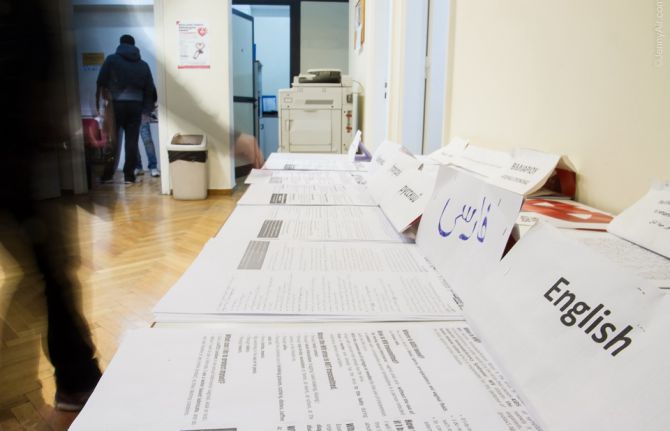

Ms Sypsa explained that the centre provided food, as well as condoms and syringes. Positive Voice, an association of people living with HIV, helped with HIV counselling, while Praksis focused on facilitating language services and identity papers for migrants.

Nikos Dedes, the head of Positive Voice, said that it played an active role during the diagnosis and referral part of the programme. “We guided them through the maze, which increased the retention of people,” he said. Mr Dedes believes that Aristotle contributed to raising awareness of HIV among people who inject drugs. “For many, HIV was a wake-up call to dealing with their drug addiction,” he said.

The programme had five rounds of recruitment in 2012 and 2013, with some participants taking part in more than one round. Aristotle’s services were provided to more than 3000 people. About 16% of the participants tested positive for HIV and had the opportunity of immediate access to antiretroviral therapy, with social workers arranging appointments. They also had priority access to opioid substitution therapy.

Ms Sypsa said that even before the end of the programme, there was a 78% decline in new HIV infections in Athens.

“Aristotle averted 2000 new HIV infections and we noted a decrease in high-risk behaviour among people injecting drugs at least once a day,” Ms Sypsa said.

She added that aside from containing an outbreak, all those involved in the programme were proud to have changed the lives of many people, linking them to HIV care and treatment.

The programme’s success drew a lot of attention. After the end of the programme, “People kept stopping by the site, looking for Aristotle employees. We had become a reference point for them,” she said.

Five years later a new programme is being started, but this time with an aim to increase care and treatment for HIV and hepatitis C for people who inject drugs.

And Mr Dedes is ecstatic, because this time Positive Voice is an integral part of the programme, with a budget. A new partner has also joined—the liver patient association Prometheus will spearhead the response to hepatitis. Mr Dedes said, “This is a true testament to the success of the programme—incorporating people from the communities.”

Feature Story

Much more than just sterile needles

12 March 2018

12 March 2018 12 March 2018The biggest question I always ask clients is, "Are you willing to change?". Charles describes his role at the Saskatoon Tribal Council Health Centre as "here to help". "We have the resources that can and will help, if and when people want and need them. I know where to point people to for housing, food and shelter. If they want detox, I know where to go—I’m very familiar with the treatment centres and I’m very familiar with the treatment cycle."

Charles is an addictions counsellor at the centre and is himself a former addict.

After almost 16 years as an alcoholic, and six years using drugs, Charles understands the issues first-hand. Charles is particularly aware of the challenges his clients endure as single parents. A single father of three, his deteriorating relationship with his children was the catalyst for him to seek help. "I didn’t really realize I had a problem, because it was so normalized. Alcohol was normal, drugs were normal, it was all normal. I went to treatment in 2007. But I knew it would be a struggle to get out."

Saskatoon is the largest city in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, a province where young indigenous people are more likely to end up in jail than to graduate from high school and suicide rates are five to seven times higher than among the nonindigenous population. There are high rates of drug and alcohol addiction and complex mental health conditions.

HIV and tuberculosis (TB) are also major health concerns among many indigenous communities. Among First Nations people in Saskatchewan, TB is 31 times the national average and the HIV rate is 11 times the national rate. Around 50% of HIV infections are through injecting drug use.

There are also high levels of stigma and discrimination in the mainstream health-care system, which is why the Saskatoon Tribal Council Health Centre is an important link to health care that the clients feel safe accessing.

At the clinic, Charles sees around six to 18 people a day. His clients come from all over the Saskatoon area, from different backgrounds and different ethnicities, with ages ranging from 18 to 60 years.

"Each and every one of them has a problem with alcohol and drugs. They come from poverty, from homelessness. They can be street people and come from very intense backgrounds. Their stories are unique, sometimes devastating to the core in terms of what they have been exposed to. But they all share one thing, they’re here because they trust us."

The centre is open 365 days a year offering health and support services. The centre offers a needle and syringe programme, providing people with sterile injecting equipment to ensure that people who inject drugs do not share syringes and needles. The clinic also offers a safe space for clients to dispose of used needles and syringes. The centre gets through more than 1.5 million sterile needles every year and has a growing client base of 2600 people, with more joining every day.

The Saskatoon Tribal Council is tackling a chronic drug and mental health crisis among indigenous people. The main objective of the centre is that it is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary drop-in clinic at the heart of Saskatoon’s low-income neighbourhoods, providing a wide range of services to treat HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis C, particularly for people of aboriginal ancestry.

The Saskatoon Tribal Council Centre is much more than just a place to get sterile needles. It is a hub, an important centre for resources and connections, a safe space and discrimination-free zone to go for help and advice. It is somewhere clients know they will be welcomed with a warm smile, a hot drink and something to eat. Staff member Twila sums it up, "People need us, and we’re making a difference."

The 61st session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) is taking place in Vienna, Austria, from 12 to 16 March 2018. The CND is the United Nations organ with prime responsibility for drug control. In line with its mandates, the CND monitors the world drug situation, develops strategies on international drug control and recommends measures to address the world drug problem.

UNAIDS urges all countries to adopt a people-centred, public health and human rights-based approach to drug use and for alternatives to the criminalization and incarceration of people who use drugs. Evidence shows that harm reduction approaches such as the Saskatoon needle–syringe programme reduce the health, social and economic harms of drug use to individuals, communities and societies. They do not cause increases in drug use. UNAIDS urges all countries to ensure that people who inject drugs have access to harm reduction services, including needle–syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy.

Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Feature Story

Measuring homophobia to improve the lives of all

08 March 2018

08 March 2018 08 March 2018A new index to measure levels of homophobia that can show the impact that homophobia has on countries has been developed.

Homophobia—defined here as any negative attitude, belief or action towards people of differing sexual orientation or gender identity—has long been known to affect public health. Gay men and other men who have sex with men who face stigma are more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviours, are less likely to adhere to antiretroviral therapy and have lower HIV testing rates. Knowledge of levels of homophobia, especially in low- and middle-income countries, is scant, however.

The new index, published in the European Journal of Public Health, combines both data on institutional homophobia, such as laws, and social homophobia—relations between people and groups of people. Data for the index were taken from a wide range of sources, including from the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. More than 460 000 people were asked questions on their reactions to homosexuality through regionwide surveys that were also used as sources for the index.

The Homophobic Climate Index gives estimates for 158 countries. Western Europe was found to be the most inclusive region, followed by Latin America. Africa and the Middle East were the regions with the most homophobic countries, with the exceptions of South Africa and Cabo Verde, which were among the top 10 most inclusive low- and middle-income countries. Among low- and middle-income countries, Colombia was the most inclusive, and Sweden was the most inclusive of all countries.

From comparing the results of the index with other data, the researchers found that countries with higher levels of homophobia were the same countries that face higher levels of gender inequality, human rights abuses, low health expenditures and low life satisfaction. Increases in a country’s Homophobic Climate Index were found to be associated with a loss of male life expectancy and a lower economic output.

The index therefore shows the damaging effects that homophobia has on the lives and well-being of everyone in a county, not just gay men and other men who have sex with men. “This index provides communities with sound data that can help them in their advocacy for more inclusive societies,” said Erik Lamontagne, Senior Economist Adviser at UNAIDS.

With knowledge of the harmful effects of homophobia, countries will be in a much better position to respond to it and improve the lives of all.

European Journal of Public Health

Feature Story

UNAIDS a top-nine gender-responsive organization

08 March 2018

08 March 2018 08 March 2018UNAIDS has emerged as a top performer in the first Global Health 50/50 report.

Global Health 50/50, an initiative that monitors the gender-responsiveness of influential global health organizations, reviewed 140 major organizations working in or influencing global health. According to the new report, UNAIDS is among the top nine health organizations in the world.

Published on 8 March, International Women’s Day, the Global Health 50/50 report was inspired by a growing concern that too few global health organizations define, programme, resource or monitor gender in their work on health or in the workplace. The report aims to show both the challenges and the way forward.

The report shows that UNAIDS has not only policies that address gender, but also concrete and time-bound gender parity targets, as set out in its Gender Action Plan. Under the plan, UNAIDS has seen the proportion of female staff rise, so that women account for 54% of UNAIDS staff. And female leaders in the field are increasing, with women accounting for 48% of UNAIDS country directors, up from 27% in 2013.

“The Global Health 50/50 survey has shown that UNAIDS’ commitment to gender equality is strong. I am resolved to building on our results and achieving all the targets of the UNAIDS Gender Action Plan,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS.

In addition to its commitment to gender equality and its workplace gender policy, UNAIDS was marked highly for having a definition of gender in its public statements, strategies or policies and having a programmatic gender strategy that seeks to improve health for everyone.

UNAIDS has long strived for gender equality and women’s empowerment, both within the UNAIDS Secretariat and elsewhere, and has recently started to review its practices and recommitted to ensuring adherence to them.

Guaranteeing the rights and empowerment of women and girls is not only a moral obligation, but a development imperative and a smart investment that safeguards the health of women and girls. Eliminating gender inequalities is one of the 10 Fast-Track commitments that Member States made at the 2016 United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Ending AIDS.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Global Health 50/50

Feature Story

Communities at the heart of the AIDS response in Zambia

07 March 2018

07 March 2018 07 March 2018Zambia has made good progress in its AIDS response. In 2016, the country had more than 800 000 people on HIV treatment, with 83% of pregnant women living with HIV accessing it. To better understand the progress, and the challenges, Michel Sidibé, UNAIDS Executive Director, visited the Chilenje health facility in Lusaka, Zambia, during a visit to the country from 5 to 7 March.

The Chilenje facility offers HIV treatment, a prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme and tailored services for adolescents and young people. At the facility’s youth-friendly space, peer educators facilitate service uptake by young people and reach out to schools and other groups within their community with counselling and sensitization.

“We need to build cities of the future where services are not only available to people, but they are also tailored to their needs. This is the rationale behind the Fast-Track cities initiative, of which Lusaka is an excellent example,” said Mr Sidibé during his visit.

The facility offers extended hours in the evening and weekends so that people who are unable to access health services outside of standard operating hours can access HIV treatment and other services.

“Young people often fall through the cracks of the health system for fear of judgement or stigma. Owing to the large number of adolescents and young people in our community, we have set up a youth-friendly space,” said Malinba Chiko, the Superintendent of the Chilenje health facility.

Earlier in the day, Mr Sidibé met with members of civil society, who raised the issue of access to HIV and sexual and reproductive health services for key populations, especially gay men and other men who have sex with men and sex workers. Mr Sidibé reiterated that civil society is at the heart of the AIDS response and, for it to be sustainable, the voice and decision-making of civil society are essential.

Region/country

Feature Story

Leveraging education to improve health and end AIDS

02 February 2018

02 February 2018 02 February 2018During the Global Partnership for Education meeting on 2 February, hosted by Senegal and France, UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé discussed the importance of education and health. “Integrating education and health is key for our success in controlling the epidemic among young people. Without effective, quality and sustainable health and education systems we are failing young people”, Mr Sidibé said. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

The First Lady of Senegal, Marieme Faye Sall, and the First Lady of France, Brigitte Macron, inaugurate a cardio-paediatric centre that provides surgical treatment for children affected by cardiologic diseases. The centre, funded by the Cuomo Foundation in Monaco, supports women and children in Senegal. Credit: UNAIDS.

Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV is crucial, as is community involvement, stressed Mr Sidibé during his meeting with Ms Sall. The western and central Africa region lags behind in access to treatment and prevention, which is why UNAIDS and partners launched a western and central Africa catch-up plan. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

Mr Sidibé also met with the Minister of Health and Social Action of Senegal, Abdoulaye Diouf Sarr, stressing that no matter who you are or where you are from, everyone has the right to health, the right to an education, the right to equal opportunities and the right to thrive. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

The Secretary General of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, Michaëlle Jean, will raise the issue of counterfeit medicines at the upcoming World Health Assembly in May. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

Minister of International Development of Norway, Nikolai Astrup, and Mr Sidibé met on the sidelines of the meeting. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

Mr Sidibé, along with the Ambassador of Luxembourg, Nicole Bintner. Luxembourg has been an active participant and donor in the western and central Africa catch-up plan. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

Good health enables a girl to thrive, to grow, to think, to explore and to contribute to her community. Knowledge of how to stay healthy and access to quality health services enable her to prevent illness, to eat well, to manage her sexual health, to have healthy babies when and if she chooses to and to nurture her own well-being. Education and health are two of the most transformative elements of a girl’s life. Credit: UNAIDS/B. Deméocq.

Region/country

Related

“Who will protect our young people?”

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025

Feature Story

Hundreds of thousands of people commemorate Zero Discrimination Day on OK.ru

06 March 2018

06 March 2018 06 March 2018On the eve of Zero Discrimination Day on 1 March, more than 890 000 viewers joined the online platform OK.ru/test to discuss zero discrimination and join the launch of the UNAIDS regional #YouAreNotAlone campaign. The discussion was live-streamed on Odnoklassniki, the leading Russian-language social media platform for countries across eastern Europe and central Asia.

The #YouAreNotAlone campaign is raising awareness about the stigma and discrimination faced by children, adolescents and families affected by HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia. The campaign features young Russian artists who each retell the personal story of an adolescent living with HIV in the Russian Federation. Most adolescents in eastern Europe and central Asia still face stigma and discrimination that prevents them from being open about their HIV status.

The broadcast also featured an interactive online film, It’s Complicated. Based on the lives of adolescents and young people living with HIV in the Russian Federation, the film tells the story of Katya, a Russian girl born with HIV who faces stigma and discrimination but also finds love and support as she grows up and adjusts to life with HIV. Some of the film’s crew and lead actors joined UNAIDS and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization staff in the OK.ru discussion.

“The goal of the #YouAreNotAlone campaign is to promote solidarity with children, adolescents and families affected by HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia for them to live with safety and dignity,” said Vinay P. Saldana, Director for the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The campaign has been promoted through social media by Vera Brezhneva, UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Victoria Lopyreva, UNAIDS Ambassador for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, and others. Everyone is encouraged to support the campaign by posting a photo on social medial with the hashtag #тыНЕодинок (#YouAreNotAlone).

“These young people are inspiring and strong,” said Ms Brezhneva. “Something is very wrong with a society where the human rights and dignity of people living with HIV are not respected. Every person living with HIV should feel our support, #YouARENotAlone!”

The campaign was also launched in Armenia, where it was supported by actors, television presenters and others. Armen Aghajanov is the first person living with HIV in Armenia who publicly disclosed his HIV status during the launch of the #YouAreNotAlone campaign on Zero Discrimination Day. He said: “People are not dying from HIV, they die from discrimination, late diagnosis, lack of access to treatment or from not taking medicines.”

Film

Region/country

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Albania

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Estonia

- Georgia

- Hungary

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Montenegro

- Poland

- Republic of Moldova

- Romania

- Russian Federation

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Tajikistan

- North Macedonia

- Türkiye

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- Uzbekistan

Related

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025

Feature Story

The moment of truth in breaking down barriers

27 February 2018

27 February 2018 27 February 2018When Robinah Babirye was at boarding school, her secret was difficult to hide. Sleeping in an all-girls dormitory, everyone knew everyone else’s business, especially around bedtime. “It was hard to bring out my medicine,” she said. “It would raise questions.”

Ms Babirye and her twin sister were hiding their HIV-positive status. Before starting at boarding school, the daughters and their mother would take their medicine daily at 10 p.m., and that was all there was to it.

Once she enrolled at university in Kampala, Uganda, in 2013, hiding became more difficult. Her room-mate was suspicious and spread rumours. Having been born with HIV, she couldn’t help feeling that life was unfair.

“At the time, I hadn’t accepted that I was living with HIV and that I had to live with it for the rest of my life,” said Ms Babirye. She described years and years of avoiding ever speaking to anyone about her regular visits to the clinic or about taking treatment. Then her mother died from cancer and she didn’t know how to cope.

Glancing above her eyeglasses, she added, “When I saw my mother fighting, it gave me strength, but when she died that became a terror.”

Ms Babirye more or less gave up. She stopped taking her medicine and drifted.

Asia Mbajja, founder and director of the People in Need Agency (PINA), a nongovernment organization for young people living with HIV in need, described appeals from distraught teenagers. She had helped many of them as children while working as a treatment coordinator at the Joint Clinical Research Centre children’s clinic.

“I kept promising them that life would change and get better, but as they grew up, their needs changed,” she said. “I needed to do something that would make a difference.”

In 2012, Ms Mbajja quit her job to start PINA. Among her first clients was Ms Babirye, whom she has known since the age of 10. She hammered over and over the importance of taking the daily dose of antiretroviral therapy.

“The problem is that all of Asia Mbajja’s upbeat encouragement would come tumbling down once she was no longer around,” Ms Babirye said. The young woman felt defined by HIV.

“When you're told that you have to take medicine for the rest of your life, coupled with the rumours and stigma, I feared I would forever be stuck,” she said. “Despite living with HIV, I am still a woman with feelings.”

Through her involvement with PINA, in 2014 Ms Babirye travelled to the International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia. The young woman felt elated to discover a world where her status seemed a non-issue, but upon her return she couldn’t help feel like there was a line she could not cross.

Ms Babirye felt tired. She wavered between ending her life and changing her life for good.

Donning an I am HIV Positive t-shirt she posted a photograph of herself on Facebook. “My heart started to beat so fast, I couldn't bear to see the comments,” she said. She paused and let out a gasp and said, “I was expecting a lot of negativity, but the comments were largely positive.”

Her twin sister, Eva Nakato, couldn't believe what she had done. After some thought, she decided she couldn’t let her sister fight alone, so she also disclosed her status.

“When people said we need more people like her it motivated us,” said Ms Nakato.

One of the first people to congratulate the twins was Ms Mbajja. Ever since, the duo have been at the forefront of PINA, testifying, mentoring and singing. Ms Nakato explained that at the children’s clinic they used to sing as a group, and at PINA they brought it to a whole new level.

“We started using music to convey HIV awareness messages," she said. Songs like Never Give Up, Yamba (Help) and ARV. Their latest projects now include launching a television series around HIV and relationships and documenting gender-based violence.

“When we met survivors of sexual abuse, that pushed me to make a movie,” Ms Nakato said, adding that videos and music can get messages across.

Ms Babirye finished her university degree last year and dreams of independence.

In the long term, she said her vision is a generation that is AIDS-free and stigma-free. “To accomplish an AIDS-free world, each individual has a responsibility to do something and break down cultural and societal barriers,” she said.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Becoming an activist to overcome discrimination

28 February 2018

28 February 2018 28 February 2018Thrown out of the house by his parents when they found out he was gay, Ezechiel Koffi didn’t give up.

“My parents said I shamed them and that I lived the life of a sinner,” the young man from Côte d’Ivoire said. What hurt him the most were his mother's insults, saying he had no respect for their religious values. He begged them to understand that he was their son and that they should accept him as he was.

Mr Koffi, 24 years old at the time, stayed for a while at Alternative, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people nongovernmental organization in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, where he had started volunteering three years earlier. He kept going to classes, although admits that at times he went on an empty stomach. Psychologically he felt beaten. “It was hard, but I couldn't hide anymore,” he said.

With the help of his older sister, his parents let him move back home after six months. Although he now had a steady roof over his head and regular meals, Alternative became his second home. He has been dedicated to it ever since. Now an HIV educator and community health worker, he proudly showed his certificates on his mobile phone.

Alternative’s project coordinator, Philippe Njaboué, describes Mr Koffi’s tireless energy. “You can call him at whatever time, day or night, he always lends a hand and he often goes out of his way to include people who have been shunned.” When asked about being a substitute family for many LGBTI people, Mr Koffi gave a hesitant smile.

The many discussion groups and support groups have helped, he said, allowing him to share his experience and help others. The once shy boy has emancipated himself. He also no longer shies away from revealing his HIV status. “It’s been 10 years now that I have been living with HIV,” he said.

Looking back, he explained, in the beginning he couldn’t always negotiate the use of a condom. He now makes a point of telling everyone that HIV is a reality. “Use condoms, there is help, you are not alone,” he exclaimed.

He described feeling fully alive among the city’s tight-knit LGBTI crowd. “I am at ease, I can express myself and it’s fulfilling,” he said. His brow furrowed, however, when he mentioned the constant discrimination he and his peers lived with. On top of the taunting and the finger pointing, Mr Koffi said social media was rampant with homophobic comments.

“We deserve the same rights as everyone else and that’s what keeps me motivated,” Mr Koffi said.

Mr Njaboué remarked that society, religion and the state all play a big part in keeping homosexuality taboo in Côte d’Ivoire. “A recent speech by Alternative’s director was tagged by a website as “The king of the homosexuals speaks”, which led to countless death threats,” he said.

Noting that this case was one of many, he believes the situation can only change if the government tackles human rights.

“Most of the population doesn’t know their rights or the law, including a lot people in charge of state security,” Mr Njaboué said. “Not only does the government need to educate people, it should also condemn unlawful behaviour,” he added.

For Mr Koffi, his visibility puts him at risk, he said, but he forges ahead. “I want to live in a world where there is no discrimination based on one’s race, one’s religion or one’s sexuality.”