Opinion

UNAIDS Executive Director addresses first Arab Forum for Equality

30 May 2022

30 May 2022 30 May 2022The first Arab Forum for Equality, held in Amman on 30-31 May 2022, is organized by the ESCWA and the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, and hosted by the Center on International Cooperation at the New York University. This is the inaugural meeting of the Forum, and the theme this year is “Towards inclusive youth employment in the Arab region”.

Following is UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima’s address:

Greetings to all participants at this first and vital Arab Forum for Equality.

Thank you my dear sister, Rola Dashti, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia for inviting me.

I’ll share three lessons that we’ve learnt about inequality.

The first lesson is a worrying one: that inequality which was already extreme is being exacerbated even further.

In 2022, nearly half of humanity, 3.3 billion people are projected to be living below the poverty line of 5.50 USD a day. (Source: Oxfam)

New Oxfam estimates show that over a quarter of a billion more people could be pushed into extreme poverty in 2022.

A new billionaire has been created every 26 hours since the pandemic began. The world’s ten richest men have seen their fortunes double. (Oxfam)

A year and a half since the first doses of a COVID vaccine were delivered, 78% of people in the US are fully vaccinated, 69 % in Europe but still under 50% (46.26%) of people in the Arab region. (Our World in Data).

We also see huge inequalities within the Arab region. United Arab Emirates has reached 97% Covid vaccination. But it is a health emergency that Algeria is only at 15 % and Yemen at just 2.2%. (Our World in Data)

Since the onset of COVID19, wealth inequality has considerable increased in the Arab region, with the richest 10% of the population now controlling more than 80% of total regional wealth. (ESCWA)

Social protection expenditures among developed countries in the Arab States are just 4.2 per cent of GDP, lagging far behind the world average of 20 per cent. (ILO)

On average health expenditure across the Arab World is just 5% of GDP, nearly half that of the European Union (9.92%). (World Bank)

The second lesson is even more worrying: that we won’t be on track to overcome health or economic crises until inequalities come down.

These kinds of extreme, intersecting, inequalities increase the risks our societies face from pandemics such as AIDS and COVID-19. And we’ve seen with COVID just how quickly a health crisis is turned by inequalities into becoming a social, a political, an economic crisis.

The third lesson is a hopeful one, but that hope depends on action: inequalities are a political choice. Courageous leaders can tackle inequalities

We can close tax loopholes and tax holidays for companies.

We can go beyond the 15% tax rate agreement for all corporate taxation around the world, up to 25%.

We can ensure taxes are paid where economic activity happens.

We can increase investment in health, education and social protection.

We can reform laws and policies so that they help us reduce harm and risk, not worsen it.

We can change the global trade rules which kept life-saving vaccines locked up in the North

Inequality is a crisis but it is not fate, tackling it is within our hands.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025

Opinion

UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima receives honorary degree from Free State University, South Africa

30 April 2022

30 April 2022 30 April 2022Following are the remarks made by UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima during the graduation ceremony held at the Qwaqwa campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa

The acting Vice-Chancellor Professor Naidoo, Distinguished leaders of this great university, Ladies and gentlemen, Fellow graduands,

I would like to thank very much the University of the Free State Sciences for this honour to be conferred with an honorary doctorate from this great university. I know that through me, you are recognizing the work of all those around the world who advance social justice, particularly who advance the right to health for all. I stand before you humbly and I am proud to join the Kovsie community!

The hall we are in bears the name of a fearless and wise man. Madiba told us that, and I quote, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”. I could not agree more. I was humbled to learn that this university bestowed an honorary doctorate on President Mandela in 2001.

Both my parents were teachers. One was a primary school teacher, the other a secondary school teacher. They were unconventional. They challenged and they encouraged us, their children. They taught us that what matters most in the world is being part of your community and standing up for justice.

For me, as for so many across the African continent, your struggle here for equality in South Africa—a struggle that we all can see is unfinished—is an inspiration. In the awful era of Apartheid even your province’s name, Free State, was itself a bitter irony. Today, whilst the long walk continues, the destination you are working to reach makes your name Free State as beautiful as those words deserve to be.

I wanted to share with you three reflections on freedom. These reflections are themselves inspired in large part by the insights of people from your country, including from the students’ movements of the past and today.

The first is that real freedom is so much more than the freedom to vote or, in the case of your country, the freedom not to be banned. Real freedom comes when every one of us is able to flourish. Central to that is education—which must be a right for all and not a privilege for a few. Every time I visit my home village in Uganda, Ruti, I meet friends of mine who did not have the opportunities I had, whose education was abruptly cut short because of an early marriage, because they had to tend to a sick family member or because they had to work for the family to survive, or they didn’t have school fees. All girls and all boys must be supported to complete a full schooling, and schools must be places of quality learning, of safety, and of empowerment—and, may I add, of joy, of enjoying oneself, one’s youth! The push that you students have made for tertiary education to open up, to reform, to reject the bad from the past, to include all, has been challenging for you, challenging for your institutions—but you have won many important steps forward and you should be congratulated for the progress that you have brought about. Congratulations! Yes, we’ve been following your movements, Rhodes must fall, fees must fall, and you inspired other students around the world to fight for inclusion and equality.

The second reflection is that none of us is free whilst anyone of us is not free. That is why the struggle for freedom needs always to be intersectional. Across the continent and across the world, South Africa has been a beacon for movements that are joined up, resisting racial inequality, embracing gender equality, and embracing equality for LGBTQ people. It is these inclusions that make a world free. So, continue to be that beacon—as a country and as a student and alumni community. Challenge stigmatization, challenge criminalization. Wherever you see anyone who’s put down because of their race, because they are a woman, because they are gay, or trans, stand up for them. Tolerance is not enough—be an ally to all who are marginalized, not only on their side but by their side.

The third reflection is that freedom is never given, it is only ever won. And it is never permanently or fully won in one moment—it must be won again and again and again. All progress has been won through collective movements, through the organising of extraordinary ordinary people. I’ve been part of the women’s movements in Africa, in the world. We’ve made a lot of progress through organizing, through holding hands, in all our diversity. The most important heroes are not those in history books or on podiums like myself, they are you—you working together, forming collectives.

Use the power that your education has given you. And use it to demand accountability and rights, for yourselves and for others. Education enabled me to go from that rural village of Ruti in Uganda, where we had no electricity, no running water, and it led me to serve in our national parliament.I was a member of parliament. It led me to lead an iconic global organisation, Oxfam International, and it led me now to lead the United Nation’s work globally to fight AIDS. From my little village.

But that power that education gave me cannot, never makes me proud in itself. It makes me responsible for what I must do to lift others, to make this world equal and just. My pride is in what I am able to do with others to make the world more just. The qualifications are mere tools to achieve a purpose.

Today is your day. You have achieved so much in getting to this day. I know you are going to celebrate as indeed you should. But let me challenge you. Let me challenge you as you leave this beautiful campus to go into the world to make a difference:

Go out there and work to build a society where every girl and boy gets the full and quality education they deserve.

Go out into the world to build a society that guarantees equality for everyone. That no one should ever again be discriminated for their gender, for their race, for their sexuality. Equality for everyone.

Go out to build collective power, I believe in the power of people. Change only happens through the power of people. Never wait for the right leaders to come and lead, you are the leader who must lead.

A more equal society will be better for everyone—for the rich, for the poor, for the able, for the less able. A more equal society is good for all—it is safer, it is more prosperous, it’s more sustainable, it’s healthier, it’s happier.

At heart I am an optimist. I want to tell you a story. This is my last challenge. You are shaped by the history of your country. The rest of us in Africa, particular of my generation, are shaped by the history of our continent including the history of your country. We watched, we followed what happened in this country and we waited for your independence, because it was going to be the independence of our entire continent. Let me tell you, when you were free, we all came rushing to see South Africa and South Africans, because for many, many years our passports had a stamp that said: “Valid for all countries except the Republic of South Africa”. We were not allowed to step here while there was still Apartheid. That was the resistance from the rest of Africa. So, when you were free we came rushing to see the remaining part of our continent come free. When my turn came and I arrived at the airport Johannesburg, it wasn’t even yet called O.R. Tambo airport, it had another name, when I arrived, I saw many young women at the immigration desk and I brought my passport to one of them. And she looked at me with a big smile and said “Welcome to South Africa” and I said “thank you”. Then she said “How is it out there in Africa?” I said “Africa?” “Yes, out there where you’re coming from, how is it in Africa?” It hit me that this young woman had not yet had consciousness that South Africa was part of Africa. And of course, I got into a discussion with her that this is Africa where you are. And she said “Ok, I know, but I mean there where you are.” So, this is my last challenge to you, my fellow graduands, you are coming from a history that cut you off from the rest of your continent. But what I leave with you is this—it’s a challenge and it’s a blessing: go out there and be proud Africans. Embrace your whole continent. Go out there knowing we have one history as a continent and we have one destiny as a continent. And serve your continent and make the most of it.

So, it’s not only an honour for me to receive this honorary degree and I thank you so much for it. It’s an honour for me to share this day with you, graduands, and to bless you as the future, or maybe let me say, the present of Africa.

I thank you.

Opinion

We cannot let war in Ukraine derail HIV, TB and Covid-19 treatment in eastern Europe

09 March 2022

09 March 2022 09 March 2022By Michel Kazatchkine — This article appeared first on The Telegraph

It is no surprise that the World Health Organization (WHO) is calling for oxygen and critical medical supplies to safely reach those who need them in Ukraine and moving to establish safe transit for shipments through Poland. But nor is the call new. We`ve been here before.

Russian annexation of Crimea and the conflict in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Eastern Ukraine in 2014 threatened the supply of HIV and tuberculosis medicines. Fragile trans-internal border efforts and financing by the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria allowed the continued supply of the medicines in the separatist territories despite the conflict during the last eight years.

One has to assume that should Russia occupy new Ukraine territories, the challenges to guarantee people living with tuberculosis and HIV access to those drugs will be just as great, high risk, if not already lost.

The separatist authorities in the Donbass and the Russian administration in Crimea also abruptly stopped opioid agonist therapy (OAT) for people who inject drugs, which resulted in much suffering and deaths from overdose and suicide.

NGOs working with affected communities in Donbass were basically closed down. Decades of fighting HIV and tuberculosis have taught us just how critical civil society, community leadership and human rights are to ending those diseases.

The Russian Federation refuses to countenance OAT as a harm reduction measure to reduce the risk of HIV transmission through shared needles.

Ukraine on the other hand, is a notable champion of harm reduction, including OAT and needle exchange programs. This matters greatly in eastern Europe and central Asia which continues to be home to the fastest growing HIV epidemic in the world.

Some 1.6 million people are living with HIV in the region (with Russia accounting for 70 per cent) and around 146,000 are newly infected each year. Drug use accounts for around 50 per cent of new infections but unprotected sex is set to become the main driver in the coming years.

Ukraine, however, has been one on of the most successful countries in the region in terms of guaranteeing access to antiretroviral drugs – 146,500 people in the past year.

These gains were at risk before the war with Covid-19 restrictions seeing a drop in people testing by a quarter in 2020. The coming weeks and months of war will cause this effort to collapse entirely.

Eastern Europe also remains the global epicentre of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis globally. Despite progress in the last ten years, TB prevalence, mortality levels and particularly, incidence of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis remain high in Ukraine which has the second highest number of cases in the region.

Drug resistant tuberculosis represents around 27.9 per cent of new tuberculosis patients and 43.6 per cent of previously treated patients and treatment success of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is around 50 per cent.

If Covid-19 halved case detection in 2020, it is not hard to imagine it being totally wiped out by the ongoing war.

As health systems collapse and treatment and prevention services are interrupted, mortality from HIV, tuberculosis, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis and Covid-19 will readily increase in Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of people are internally displaced and cities such as Lviv are running short of medicines and medical supplies.

Scarily, the fallout of the invasion will also go beyond Ukraine: over a million refugees have already fled for their lives. The impact of this will be felt across border towns and areas in central Europe whose response to tuberculosis, HIV and more recently Covid-19, has been fragile.

Border locations and neighboring countries will have to anticipate and address an avalanche of new health needs. We are at an impasse: international cooperation and solidarity towards the Eastern European region has not been a strong feature of the last two years of the global pandemic response.

The arrival of WHO health supplies and the formation of a safe corridor for refugees are fragments of good news in this unfolding tragedy, but we need so much more.

Health systems and facilities must be protected, be functional, safe and accessible to all who need essential medical services, and health workers must be protected.

Michel Kazatchkine is Course director at the Graduate Institute for International Affairs and Development in Geneva, Switzerland, and the former UN Secretary General and UNAIDS special Envoy on HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe and central Asia. Previous to that he was the Executive Director of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and malaria.

Region/country

Related

Opinion

Forty years of AIDS: Equality remains central to quelling a still-potent epidemic

01 December 2021

01 December 2021 01 December 2021by Edwin Cameron

On 1 December, we mark World AIDS Day.

This year marks a sombre anniversary. On 5 June 2021, it was forty years since disturbingly unexplained cases of illness and death – later called AIDS – were first officially tabulated. These four decades have yielded enormous medical and scientific progress – but too many deaths and far too much stigma remain very much with us.

Too many still elude testing, or die in silence and shame; treatment does not reach all who need it – and inequality and discrimination impede our global response.

Today, I am able to pen this because life unexpectedly afforded me survival from AIDS. Twenty four years ago, I started on life-saving antiretroviral treatment – enabling me to bear witness to how discriminatory laws and policies damage those this fearsome epidemic imperils. Let me explain.

Around Easter 1985, in my early 30s and setting out on my career, I became infected with HIV. In those terrible years, no treatment existed: HIV meant certain death. Stigma and fear choked all who had or were suspected of having HIV or AIDS.

Like many others, I kept my HIV a secret. I hoped against hope that I would escape the spectre of death. No. Twelve years later, AIDS felled my body. With the certainty of death impending, I became terribly ill.

But my privileges gave me access to treatment and care. I had loving family and friends, and my job as a judge to return to. With early access to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, I survived.

In 1999, I spoke publicly about living with HIV. I explained that ARVs had saved me from certain death – but that millions more in Africa were denied them.

Today, I remain one of the only people holding public office in Africa to speak publicly about being gay and about living with HIV. I say this not to claim credit, but because so much shame, fear, ignorance and discrimination still silence too many in too many places.

From my life, in my own deepest being, I know the power of stigma, discrimination, hatred and exclusion.

And, after twenty-five years as a judge, I have been witness to three facts. First, the destructive power of stigma and shame. Second, the damage punitive and discriminatory laws inflict on public health responses. Finally, how insufficient legal protections and inadequate legal remedies make the cruel load of HIV/AIDS infinitely worse.

Why equality is at the heart of the response to HIV/AIDS

Some 37.7 million people globally are living with HIV. For most of us, heartening developments have alleviated the burdens of death and illness and shame. Today, we can fulfil our aspiration to reach the 90-90-90 target (90% of those with HIV must know their status, 90% of them to access treatment, and 90% of those to attain viral suppression).

In Africa, the epidemic however has a particular poignancy. Two-thirds of HIV cases are in Sub-Saharan Africa – and here young women make up 63% of new HIV infections.

As acutely, key populations (sex workers, LGBTQI+ people, drug users, those incarcerated, men who have sex with men) account for 65% of new HIV infections worldwide.

Given these striking facts, the new strategy the UN body fighting to mitigate the epidemic – UNAIDS – announced was welcome. This highlights how inequalities exacerbate AIDS. Ending them is therefore at the core of UNAIDS’s new approach.

A rights-based approach is right. It illuminates how human rights are all interconnected. The AIDS epidemic vividly instances this: the right to health cannot, in though or practice, be disconnected from the right to equality.

The lesson is clear: to overcome AIDS by 2030, we must achieve greater equality for all.

The good news is that protecting and respecting rights works in mitigating AIDS. Evidence from UNAIDS powerfully shows how “inequalities fuel the HIV epidemic and block progress towards ending AIDS.” As The Lancet rightly notes: “The success of the HIV response is predicated on equality – not only equality in access to prevention, care, and treatment … but also equality under the law.”

Human rights programs and sensible law reforms reduce stigma and discrimination. Yet far too little funding and effort is channeled here. The result is plain – in far too many societies, stigma sits as a dark burden on the backs of those living with and at risk of HIV and AIDS; discrimination permeates the societies and their laws – and repeal of misplaced, punitive laws is agonizingly slow.

No to punitive and discriminatory laws

Punitive and discriminatory laws target key populations most at risk of HIV/AIDS. They hit on peoples’ sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, drug use, and sex work.

Thus, too many countries still criminalize LGBTQI+ persons. And transgender women are at enormously higher risk of contracting HIV.

And no one suffers discrimination solely on only one ground. The poisonous perils of discrimination mingle in a multiplicity of hostile grounds – what is rightly called “intersectionality”. A sex worker is attacked for their sexuality, gender, socio-economic status, and HIV status. The disquieting result: sex workers, have a 26 times higher risk of contracting HIV.

In all this, the brutal force of the criminal law clenches the throat of good AIDS work. It intensifies inequalities, unfairness and exclusions.

The point is this: criminalizing people living with HIV and punishing key populations undermines prevention efforts. It reduces uptake of services. And it can increase HIV infections.

These punitive laws do not merely “leave people behind”. They actively shove them out. They increase fear and stigma – and in turn push those most at risk away from health services and social protections.

As UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima, powerfully recounted, “Stigma killed my brother, he was HIV positive and would be living today but he was afraid to go to the clinic to fetch his ARVs because people he knew would find him there and would judge him.” Her conclusion? “We have to fight stigma and discrimination, they kill.”

Additional knock-on effects harm our societies. Discrimination seeps into data and evidence collecting, where criminalized and stigmatized populations are often under-represented and omitted.

This reflects their day-to-day reality: their experience of an extreme form of stigma – being negated, invisible, wiped out.

This negation is profoundly harmful. It means that we do not know whether services are accessible and acceptable. It means important information may not be provided. It means violence and discrimination against invisible populations remain unknown, unaddressed.

So, we must ask: How can you remove barriers to access services if you do not even see the persons they are crushing? What can we do?

At least one answer: We can help create enabling, empowering, safe-guarding legal environments.

An enabling legal environment

The response to AIDS is linked to democratic values and functioning legal systems. The rule of law, freedom of expression, freedom to protest, and other basic human rights matter.

Creating an enabling legal environment is a critical step. It means we employ the law to empower rather than oppress. It means scrapping pointlessly punitive criminal laws. It means achieving equality before the law.

Access to justice, the demand for law reform, awareness as well as education campaigns and vibrant civil society activism, embracing key populations, are pivotal. These foster beneficial change and help ensure accountability for human rights violations.

The last forty years showed us this. Brave, principled, outspoken activists, from ACT UP in New York and the Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa, secured life-saving gains in treatment for AIDS. The activists’ struggle was for justice and for finding the most effective response to AIDS. In South Africa, the activists challenged President Mbeki’s denialist government in the highest Court – which ordered him to start providing ARVs.

For them, as it was for me, and still is for too many today, the battle was about life versus death, wellness versus sickness, science versus harmful myths, discrimination versus justice and equality – and about how fair practices make sound public health sense and save lives.

The new UNAIDS strategy embraces this history. It seeks to ensure access to justice and accountability for people living with or affected by HIV and key populations. Rightly, it calls for: increased collaboration among key stakeholders, for supporting legal literacy programs, and for increased access to legal help. From the international community, it also provides for substantial commitment, greater investments, and strategic diplomacy.

The Covid-19 pandemic has not alleviated these goals – its impact on inequality has made them more pressing. Anti-infection lockdowns led to HIV and AIDS service disruptions (healthcare facilities were closed or resources were reallocated to Covid-19 or there were shortages of ARVs).

On the other hand, lessons have been learnt, and mRNA technology could speed up the development of AIDS vaccines.

Though there is still no cure, AIDS is no longer a death sentence. Twenty four years after taking my first ARVs, I am living a vibrant, joyful life. Our challenge lies within ourselves, and our societies: it is to overcome fear, discrimination and stigma to ensure life-saving treatments and messages are equally and equitably accessible.

Ending AIDS by 2030 is a realistic goal. But to achieve it, we must respect, protect and fulfil the basic rights of those living with and at risk of HIV. We must embrace democratic aspirations, place key populations at the center of our response, provide resources to reduce inequalities as well as inequities, and foster legal environments that enable us to end AIDS.

These harsh last forty years have shown us this: with enough support, science, focus and love, we can end AIDS.

Opinion

Fulfilling our promise to adolescents and young people

03 December 2021

03 December 2021 03 December 2021By Prof. Sheila Tlou — Republished from Health Times

My years of work in HIV prevention have taught me a few things. Among them, one of the important things I have learnt is that if people do not know how to protect themselves or how to access treatment, they will not be able to prevent HIV or lead happy and fulfilling lives with HIV. Therefore, information and education is key. But its not the only thing needed. I might have the information that unsafe sex may expose me to HIV or other STIs, but I may still go ahead and engage in unprotected sex. This means that the motivation and means also have to be provided. The other thing I have learnt about imparting knowledge is that you have to do it before it is too late. People need to know how to prevent an illness before they come in contact with it or before they act in a way that allows their body to be vulnerable to it.

Children today are leading the charge on a number of global issues – be it girls’ education, be it climate change or HIV. We have at least two world leaders on the issue of girls’ education and of climate change – Malala and Greta – who began their leadership as children and made the world listen to them. Why is this possible in today’s day and age? Because we are all more and more connected, and children and young people are now growing up with the internet as well as other media.

But no one is born with the knowledge to handle this media or to know how to prevent illness. We all learn this. How to use a mosquito net to sleep in for avoiding malaria. How to wash our hands to prevent bacterial infection or COVID. How to use a condom to prevent HIV or other STIs. These are learnt behaviours and someone reliable and trustworthy needs to teach us or we are unlikely to listen.

All this to say that I know from my lifetime of experience, and the world knows through over a decade of evidence, that when you provide good quality, contextual and developmentally appropriate sexuality education to adolescents, it is effective. It results in less HIV infections, less early or unintended pregnancies and less unhappy couples!

Puberty, healthy relationships, and preparation for building a home and having a family are among those aspects of life that CSE teaches in schools. Addressing such topics can no longer be avoided because children are already being exposed through many, widely available channels. Unless a trusted source addresses it first, our children are at risk of taking wrong turns in life because of the things they read on the Internet, see on TV, or discuss with their friends. CSE offers comprehensive education – not just about puberty, healthy relationships, and preparation for starting a family. Indeed, the goal of is to support children in becoming well-rounded individuals. CSE teaches how to carefully think actions through and make decisions that are mature and healthy.

Here we are at the cusp of renewing our promise to our children and young people in east and southern Africa that we will give them the best possible education for their health and well-being, and access to the services they need. We are promising to them that we will do all we can for their brighter future. It tires me that there are still some people who want to rob our children of the education that gives them all the possible options and choices of protection, including abstinence, delaying sexual activity, condoms and other contraception. It tires me that there are some trouble makers spreading misinformation about sexuality education, when we know that CSE leads to healthier, happier and more fulfilled young people who have the information, attitudes and skills to make better life choices for themselves.

Let us reject this misinformation, trust our governments, and work together towards a better, healthier Africa.

Prof Sheila Tlou is the Co-Chair of the Global HIV Prevention Coalition, Former Minister of Health Botswana, distinguished advocate for human resources for health issues and a recognized visionary leader and champion through her initiatives on HIV and AIDS, gender, and women's health.

Related

“Who will protect our young people?”

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025

Opinion

How to end the AIDS epidemic in western and central Africa

31 October 2021

31 October 2021 31 October 2021By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director

The AIDS epidemic in western and central Africa is an ongoing emergency. The early gains made against HIV in this region have not been translated into the sustained progress that has been made in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Last year, there were 150 000 AIDS-related deaths in the region, and 200 000 people became newly infected with HIV. Every week more than 1000 adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years become infected with HIV in the region; 1.2 million people in western and central Africa are still waiting to initiate life-saving HIV treatment. Only 35% of children living with HIV in western and central Africa are on treatment.

Now the COVID-19 crisis has obstructed services and exacerbated the inequalities that drive the AIDS epidemic. If we don’t act now, not only will many more lives be lost, but containing the AIDS pandemic will be more difficult and expensive in the coming years.

Ending AIDS is achievable: there is a tested set of approaches that are proven to work, including in challenging settings.

From Cabo Verde’s leadership on the elimination of vertical transmission of HIV, to Cameroon’s decision last year to eliminate user fees for all HIV services at public health facilities and accredited community sites, examples that light the way are already there. By aligning policy with the evidence of what has succeeded, we can end AIDS as we promised.

Countries and communities are already leveraging the experience and expertise of the AIDS response to reduce the impact of COVID-19 across this region. From Côte d’Ivoire, to Guinea, to Senegal, public health authorities, international organizations, civil society actors and communities of people living with and affected by HIV have worked together to ensure that people living with HIV continue to receive their medication, to deliver care and prevention services in safe and innovative ways, to deliver food to people who have lost their incomes in lockdown, to convey messages about the importance of hygiene and social distancing in order to stay well and to dispel myths that feed stigma and discrimination and weaken public health messaging.

This spirit of cooperation and partnership is vital for stronger pandemic responses.

This week, hosted by the President of Senegal, Macky Sall, UNAIDS and the Civil Society Institute for HIV and Health in West and Central Africa are organizing a summit in Dakar on how to close the gaps in the region’s HIV response and strengthen pandemic preparedness.

Here are three of the bold actions we need to take.

First, embrace and enable communities to be at the centre of planning and delivery.

Communities know the situation on the ground—they must be given the resources and the space to lead. Countries need to ensure an enabling environment for communities to be involved in providing services as an integral part of the public health response, be involved as co-planners, be able to highlight experiences and concerns and be able to play their essential role ensuring accountability.

Countries need to lift those legal, policy and programmatic barriers that hold this back, and to scale up financial support to unleash the incomparable contribution of communities.

Second, increase investment.

Countries need to increase the scale of provision in prevention, testing and treatment and eliminate all financial barriers to ensure universal access to services.

The Abuja commitment to invest 15% of government budgets in public health needs to be met. Joint commitments made by health and finance ministers at the Africa Leadership Meeting to increase domestic revenues dedicated to health must be fulfilled.

International donors too have to step up with support at the time of the worst crisis in decades. Enabling the required fiscal space will require debt cancellation to support governments in scaling up investments in health and in tackling the social drivers of HIV and pandemic risk.

International action to prevent harmful tax competition and illicit financial flows is likewise key. It is difficult to advance towards fair and progressive taxation, and grow revenues, when large corporations and high-net-worth individuals are systemically enabled internationally to evade the taxes the ordinary citizen must pay, and which are essential for health, education, social protection and economic investment.

Third, address the inequalities that drive the epidemic.

COVID-19 has once again shown the world how epidemics thrive on inequalities, both between countries and within them. The new UNAIDS strategy adopted earlier this year puts the fight to end inequalities at the centre of the mission to end AIDS.

Inequalities drive HIV. Vulnerable groups of people represent 44% of new HIV infections in western and central Africa. Their partners represent a further 27%.

The ECOWAS Strategy for HIV, TB, Hepatitis B & C and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights among Key Populations puts it so well:

“the protection of human rights for all members of each key population is crucial to success. Laws that discriminate or create barriers should be reformed, to ensure that key populations are free from stigma, discrimination and violence and their vulnerability to HIV is reduced.”

Gender inequality likewise drives HIV: of the new HIV infections among young people in western and central Africa, almost three quarters are among adolescent girls and young women. The issue is power.

Research shows that ensuring that girls complete secondary education reduces their risk of acquiring HIV by up to half, and that combining this with a package of services and rights for girls’ empowerment reduces their risk further still.

The Education Plus initiative, co-convened by UNICEF, UNESCO, UNFPA, UN Women and UNAIDS, with governments, civil society and international partners, is helping to accelerate the actions and investments needed to ensure that every African girl is in school, safe and strong.

What we need to do to end AIDS is also what we need to do to enable Africa to rise.

Governments, international organizations, scientists, researchers, community-led organizations and civil society actors cannot be successful alone, but together they can create an unbeatable partnership and an unstoppable force to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Opinion

The quest to end the COVID-19 and HIV pandemics

25 October 2021

25 October 2021 25 October 2021Opinion by

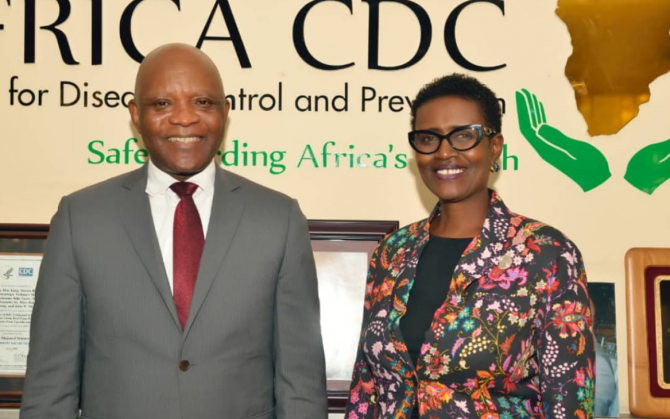

Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS

Chikwe Ihekweazu, Director General of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control

At a time when millions have lost work, Queen Kennedy got a new job. As a woman living with HIV in Nigeria, she answered the call to become a community pharmacist. Lockdowns lowered access to HIV treatment and prevention. But through an International Community of Women Living with HIV West Africa initiative, Queen and her colleagues home deliver HIV medicines. They also conduct adolescent HIV prevention sessions.

“I willingly accepted to do this work because as a woman living with HIV, I know what it really means staying without antiretroviral therapy,” Ms Kennedy said. “People may develop drug-resistant strains, whose long-term effects could be worse than COVID-19.”

Stories like this remind us that COVID-19 did not meet a world free from health crises. Today, we are witnessing COVID-19’s collision with a 40-year-old HIV pandemic that has claimed 37 million lives globally. At the same time, most of the developing world is still grappling with recurring and emerging disease outbreaks that have disrupted lives and left long-lasting scars. In some regions these health emergencies have become endemic, driven by interlinked vulnerabilities, disparities and inequalities.

From 24 to 26 October, nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, global health leaders across sectors will gather in Berlin, Germany, for the World Health Summit. How do we leverage this moment? What lessons can we draw from responding to COVID-19, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, Ebola and other health emergencies? And how can we enhance systems for health around the world and build a global health architecture that serves us all, leaving no one behind?

Early responses to HIV took place in emergency mode—but in rapidly building our capacities, the AIDS response has built clinics and labs, expanded the health and science workforces and supported community-led systems that have been critical in the COVID-19 response. We now know that these elements have been imperative for broader pandemic prevention, preparedness and response. As a result, life-saving HIV treatment is being delivered to 27.5 million people around the world, resulting in a 47% reduction in AIDS-related deaths since 2010. Global solidarity and shared responsibility, science, civil society activism, politics and the private sector have been critical in achieving this progress.

HIV infrastructure has been instrumental to making the COVID-19 response rapid, decisive and agile. Countries such as South Africa, India and Nigeria repurposed and redeployed this capacity to expand surveillance, testing and community-led responses. This was particularly important in Nigeria, where at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic there were just four laboratories that had diagnostic capacity for COVID-19. By repurposing some existing HIV and tuberculosis laboratories and through other interventions led by the country, there are now more than 150. One of the key lessons from previous pandemics for this one, is to build an integrated response from the onset.

However, this infrastructure and capacity does not exist everywhere. And most worryingly, we are witnessing inequality between countries in terms of access to COVID-19 vaccines. The lessons and solidarity from the AIDS response are being ignored as COVID-19 vaccine production technologies and know-how remain in the hands of a few pharmaceutical companies and vaccine manufacturers. While more than 60% of Europeans have been vaccinated, only 4% of Africans have had their shot. Nine out of 10 people in developing countries are unlikely to get a dose this year. We need to reclaim the benefits of solidarity and interconnectedness that will allow all of us to recover from this pandemic and build a better future. The pandemic and post-pandemic worlds need a humanity where every life is valued.

Pandemics thrive on human-made inequalities. These we can and must close. At the intersections where COVID-19 and HIV collide, we find the most-at-risk and vulnerable people. They were among the first to lose their livelihoods and continue to face unequal access to health care and social services. Inequality in access to technology further deepened the impact of COVID-19. It created a divide of who could continue to work and earn and who could continue their studies.

Registration for vaccination over digital platforms has excluded those who cannot access those platforms. Delivery of vaccination through fixed facilities has the potential to leave out marginalized communities poorly served by the traditional health system and deepen inequality in access. To end AIDS and end COVID-19, we need to end inequalities, which requires a whole-of-society approach—where communities are at the centre of prevention, preparedness and response.

The pace of the spread of COVID-19 highlights the need for an urgent response. Ebola quickly overwhelmed the health systems of affected countries in West Africa, but the response capacity across countries was lost thereafter. With COVID-19 and the continued response to HIV, the focus must be on drawing on local and regional capacities and strengthening national health systems to prevent, detect and respond, not just to one emerging disease, but to any.

If we get this right, so much is won. If we get it wrong, the global health deficit grows.

As global leaders we owe several things to the next generation. We owe them adaptable systems capable of addressing the multi-dimensional aspects of pandemic prevention and preparedness. We owe them comprehensive and integrated health services harnessed through universal health coverage to ensure equitable and affordable access to health by all. We owe them true global partnerships and collaboration for better data and knowledge-sharing. We owe them faster local and global analytics to inform innovation and decision-making. And we owe them short-term public health responses and longer-term development approaches that factor in local vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, we need a synergized, coordinated public health and development response that will allow us to end the two current, colliding pandemics and be better prepared for the next.

Opinion

We must have a #PeoplesVaccine, not a profit vaccine

09 December 2020

09 December 2020 09 December 2020By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director

The first shots of the COVID-19 vaccine are being administered in the UK this week-a triumph for the British people and a remarkable achievement for all those involved. This historical event, celebrated, quite rightly with much relief and fanfare, shows just what can be done when investment and political will combine to overcome a public health threat. These efforts will undoubtedly save thousands, if not millions of lives.

Yet we are far from claiming victory. New statistics released today by the People’s Vaccine Alliance show that 9 out of 10 people in poor countries are set to miss out on COVID-19 vaccine next year. Once again poorer countries find themselves at the back of the queue and will have to watch many more of their people die before a vaccine becomes affordable for them.

This tragically echoes the early days of the AIDS response when treatment was only available to the rich while poorer countries had to wait years before they could offer their people the same life-saving medicine. This was an avoidable tragedy and we cannot let this happen with the COVID-19 vaccine.

Rich countries have acquired enough doses to vaccinate their entire populations nearly three times over next year. Indeed, rich nations representing just 14% of the world’s population have bought up 53% of all the most promising vaccines so far.

Our best chance of staying safe from COVID-19 is to have vaccines, diagnostics and treatments that are available for all. No-one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is safe. The response to COVID-19 is reinforcing existing inequalities within and between countries and the global economy will continue to suffer so long as much of the world does not have access to a vaccine.

The current system enables pharmaceutical corporations use government funding for research but maintain monopoly on medicines keeping their technology secret to boost profits. As we learnt from the HIV crisis, this monopoly costs many lives. If history has taught us anything, it is that pharmaceutical corporations create and protect monopolies to maximise profits as a goal higher than improving public health.

Things are moving fast on the vaccine front, yet efforts to improve access to a vaccine are moving far too slowly. The Pfizer /BioNTech vaccine we have seen has already received approval in the UK and it is likely to receive approval from other countries, including the US and EU, within days. Two further potential vaccines, from Moderna and Oxford (in partnership with AstraZeneca) are expected to submit or are awaiting regulatory approval. The Russian and Chinese vaccines have announced positive trial results. Yet all of Moderna’s doses and 96% of Pfizer/BioNTech’s have been acquired by rich countries.

In welcome contrast Oxford/AstraZeneca has pledged to provide 64% of their doses to people in developing countries. However, despite their actions to scale up supply, they can still only reach 18% of the world’s population next year at most.

We must have a #PeoplesVaccine, not a profit vaccine. Unless urgent action is taken by governments and the pharmaceutical industry to make sure enough doses are produced, COVID will continue lay existing inequalities bare. Pharmaceutical corporations and research institutions working on Covid19 vaccines must share the science, technological know-how, and intellectual property related to the vaccines to maximise production by other quality producers. This will allow that enough safe and effective doses to be supplies to all who need the vaccines at the same time. And there is already a global mechanism that facilitates this sharing: the World Health Organization COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP).

I remember the days of the creation of the Medicine Patent Pool for HIV medicines which resulted in production of millions of doses of affordable antiretrovirals that are currently used by people in developing countries. Therefore, we have an example to learn from and make C-TAP works for the millions awaiting a vaccine.

Governments must do everything in their power to ensure COVID-19 vaccines are made a global public good—free of charge to the public, fairly distributed and based on need not ability to pay. A first step would be to support South Africa and India’s proposal to the World Trade Organisation Council this week to waive intellectual property rights for COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatments until everyone is protected.

The campaign for a #PeoplesVaccine is gaining momentum. Last week in the US, more than 100 high-level leaders from public health, faith-based, racial justice, and labour organizations, joined former members of Congress, economists and artists to sign a public letter calling on President-elect Biden to support a People’s Vaccine. In the EU, a broad coalition of health worker trade unions, NGOs, activist groups, students associations and health experts launched a European Citizens’ Initiative for a people’s vaccine.

Now is time for pharmaceutical companies and governments to step up and ensure that a COVID-19 vaccine is available to everyone, everywhere, free at the point of use. Only then will the world begin to turn the tide on the COVID-19 crisis and ensure that everyone can stay safe and prosper.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Our work

Video

Opinion

We will not defeat COVID-19 without including Africa in the global response

25 May 2020

25 May 2020 25 May 2020This article was first published on 19 May 2020 here

In much of the global COVID-19 conversation, Africa is barely mentioned. But the risks which the COVID-19 crisis brings are even greater in Africa than elsewhere – and those risks will be compounded if Africa is marginalized in the global response. Beating COVID-19 in Africa, in turn, is essential for beating it worldwide. African leadership and global solidarity are both essential to overcoming the COVID-19 crisis in Africa, and Africa’s citizens demand nothing less.

Economic and social determinants of ill-health are strong predictors of the likelihood of dying from COVID-19. The greatest risk will be for poor people in poor countries who have a much higher burden of existing illness, and of whom hundreds of millions are malnourished or immunocompromised. While Africa does have vital experience of managing epidemics, it also has health systems which are largely under-resourced and which are still often inaccessible to the poor, and not up to the job of beating COVID-19.

Beating back COVID-19 in Africa is possible, but not under business as usual. We need urgently to accelerate access to testing; ensure equal access to equipment to protect frontline medical workers and treat the sick; ensure that health systems are adequately funded; agree globally that any COVID-19 vaccine is free for all; and ensure that the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis are mitigated through large-scale social protection measures and sustainable economic development which reduces inequality.

The African Union, through its Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, is taking a strong lead in the response to the epidemic. It has created a new partnership as part of the Africa Joint Continental Strategy for the COVID-19 response, the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing (PACT), which has been fully endorsed by the Bureau of African Union Heads of State and Governments. UNAIDS is proud to be the first to sign up for this partnership, which aims to close the gap in testing by supporting the efforts of African countries to rapidly scale up their capacity to test and trace. As we have seen in other regions of the world this is crucial to reduce the number of infections and deaths. PACT also calls for the rapid establishment of an Africa CDC-led system for pool procurement of diagnostics and other COVID-19-related response commodities.

The good news is that countries are stepping up: at the beginning of May, South Africa had conducted more than 300,000 tests, with Ghana on more than 100,000. They have done so in part by leveraging the exiting HIV testing infrastructure, and other countries such as Nigeria plan to follow suit. But Africa CDC estimates that Africa needs 10 million tests to respond to the pandemic in the next four months. In addition, the World Health Organization estimates that 100 million face masks and gloves, and up to 25 million respirators, will need to be shipped to African countries every month to respond effectively to COVID-19, at a time when there is a global scramble for supplies.

Worldwide, production of test kits and essential medical supplies must be ramped up and there must be globally coordinated efforts to get the tests and personal protective equipment to the places and people most in need: in Africa that means to our high-density population townships and to our frontline medical staff and community health workers responding to the epidemic. We also need to leverage existing HIV services to boost COVID-19 testing, isolation, contact tracing and treatment capacities.

Now more than ever, African countries need to prioritize investment in essential services. This must include a real commitment to tackle massive corporate tax evasion and ensure that those with the broadest shoulders pay the most tax, including an end to corporate tax exemptions. Now more than ever, also, we need global solidarity to fund a multi-billion-dollar response that includes low and middle-income countries in Africa and the rest of the world. This includes fully funding the United Nations US$2 billion COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan as well as providing grants to support the abolition of user fees for health services. This pandemic has shown that it is in everyone’s interest that people who feel unwell should not check their pocket before they seek help. As the struggle to control an aggressive coronavirus rages on, the case to end-user fees in health immediately has become overwhelming. International financial institutions and private financial actors need to both extend and go beyond the temporary debt suspensions that have recently been announced - Africa’s debt is about 60% of the continent’s gross domestic product which is completely unsustainable. We must free governments to invest in the response and to strengthen publicly funded health care provision underscored by the principle that everyone has the right to health. In responding to COVID-19, we must be on our guard that resources are not diverted away from other health threats such as the HIV epidemic, tuberculosis, or malaria, which are already taking a heavy toll on Africa.

Modelling conducted on behalf of the World Health Organization and UNAIDS has estimated that if efforts are not made to mitigate and overcome interruptions in health services and supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to more than 500000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses, including from tuberculosis, in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020–2021.

There also needs to be prior international agreement that any vaccines and treatments discovered for COVID-19 will be made available to all countries and be free for all. We must not repeat the experience of the HIV epidemic, where medicines remained beyond reach for too long and millions died, while others are still waiting to initiate treatment today.

A strong recovery is key to building the resilient societies capable of withstanding the next unexpected event. Given the interconnectedness between health and livelihoods, all countries will need to strengthen social safety nets to enhance resilience. They will need too to build more sustainable economies, including decent, well-paid jobs for Africa’s young population and recognition for the undervalued and often unpaid care work carried out by women.

If it has taught us anything, this pandemic has shown how interconnected we are as a global community and that, as the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, has said, the world is only as strong as its weakest health system. Any global response to COVID-19 which marginalizes Africa’s citizens would not only be wrong, it would be self-defeating. Moreover, Africa’s citizens would not stand for it. Even in the exceptional constraints of this pandemic, ordinary Africans have been organizing to insist on their rights to healthcare and on their rights to social protection. As Africans, we stand with them in refusing to be sent to the back of the COVID-19 queue.

Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS

John Nkengasong, Director of Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Related

Opinion

Health: providing free health for all, everywhere

20 May 2020

20 May 2020 20 May 2020By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director — First published in World Economic Forum's Insight Report (May 2020)

Recognizing the public-health catastrophe

As we have seen in wealthier countries, economic and social determinants of ill-health are strong predictors of the likelihood of dying from COVID-19. The greatest risk will be for poor people in poor countries who have a much higher burden of existing illness, and of whom hundreds of millions are malnourished or immunocompromised. For the quarter of the world’s urban population who live in slums, and for many refugees and displaced people, it is not possible to socially distance or to constantly wash hands.

Half the world’s people cannot access essential healthcare even in normal times. While Italy has one doctor for every 243 people, Zambia has one doctor for every 10,000 people. Mali has three ventilators per million people. Average health spending in low-income countries is only $41 per person a year, 70 times less than high-income countries.

The pressure the pandemic will place on health facilities will not only affect people with COVID-19 – anyone needing any care will be impacted. This has previously been the case. During the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone there was a 34% increase in maternal mortality and a 24% increase in the stillbirth rate, as fewer women were able to access both pre- and post-natal care.

The International Labour Organization predicts 5 million-25 million jobs will be eradicated, and $860 billion-$3.4 trillion will be lost in labour income. Mass impoverishment will make treatment inaccessible for even more people. Already every year 1 billion people are blocked from healthcare by user fees. This exclusion from vital care won’t only hurt those directly affected – it will put everyone at risk, as a virus can’t be contained if people can’t afford testing or treatment.

Lockdowns without compensation are, at their crudest, forcing millions to choose between danger and hunger. As in many developing country cities, over three quarters of workers are in the informal sector, earning on a daily basis, many who stay in will not have enough to eat and so large numbers will ignore lockdown rules and risk catching the coronavirus.

As we have seen in the AIDS response, governments struggling to contain the crisis may seek scapegoats – migrants, minorities, the socially excluded – making it even harder to reach, test and treat to contain the virus. Donor countries may turn inwards, feeling they can’t afford to help others and, as the presence of COVID-19 anywhere is a threat to people everywhere, this will not only hurt developing countries, it will also exacerbate the challenge in donor countries too.

And yet, amid the pain and fear, the crisis also generates an opportunity for bold, principled, collaborative leadership to change the course of the pandemic and of society.

Seizing the public-health opportunity

Contrary to conventional wisdom that responding to a crisis takes away the capability needed for major health reforms, the biggest steps forward in health have usually happened in response to a major crisis – think of the post-Second World War health systems across Europe and in Japan, or how AIDS and the financial crisis led to universal healthcare in Thailand. Now, in this crisis, leaders across the world have an opportunity to build the health systems that were always needed and which now cannot be delayed any longer.

Universal healthcare

This pandemic has shown that it is in everyone’s interest that people who feel unwell should not check their pocket before they seek help. As the struggle to control an aggressive coronavirus rages on, the case to end user fees in health immediately has become overwhelming.

Free healthcare is not only vital for tackling pandemics: when the Democratic Republic of the Congo instituted free healthcare in 2018 to fight Ebola, healthcare utilization improved across the board with a more than doubling of visits for pneumonia and diarrhoea, and a 20%-50% increase in women giving birth at a clinic – gains that were lost once free healthcare was removed. Free healthcare will also prevent the tragedy of 100 million people driven into extreme poverty by the cost of healthcare every year.

Because COVID-19 has no vaccine yet, all countries will need to be able to limit and hold it. The inevitability of future pandemics makes permanent the need for strong universal health systems in every country in the world.

Publicly funded, cutting-edge medicines and healthcare must be delivered to everyone no matter where they live. To enable universal access, governments must integrate community-led services into public systems. This crisis has also highlighted how our health requires that the health workers who protect and look after us are themselves protected and looked after.

Given the interconnectedness between health and livelihoods, all countries will also need to strengthen social safety nets to enhance resilience. COVID-19 has reminded the world that we need active, accountable, responsible governments to regulate markets, reduce inequality and deliver essential public services. Government is back.

Financing our health

Many developing countries were already facing debt stress leading to cuts in public healthcare. In recognition that worldwide universal healthcare is a global public good, lender governments, international financial institutions and private financial actors need to both extend and go beyond the temporary debt suspensions that have been announced recently. The proposal by the Jubilee Debt Campaign and hundreds of other civil society organizations sets out the kind of ambition required.

Bilateral donors and international financial institutions, including the World Bank, should also offer grants – not loans – to address the social and economic impacts of the pandemic on the poor and most vulnerable groups, including informal sector workers and marginalized populations. Support to developing countries’ ongoing health system costs needs to be stepped up. It would cost approximately $159 billion to double the public health spending of the world’s 85 poorest countries, home to 3.7 billion people. This is less than 8% of the latest US fiscal stimulus alone. It is great to see donor countries using the inspiring and bold language of a new Marshall Plan – but currently pledged contributions are insufficient.

Business leadership

A new kind of leadership is needed from business too; one that recognizes its dependence on healthy societies and on a proper balance between market and state. As President Macron has noted, this pandemic “reveals that some goods and services must be placed outside the rules of the market”. ’The past decade has seen a rapid increase in the commercialization and financialization of healthcare systems across the globe. This must end.

As a group of 175 multimillionaires noted in a public letter released at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2020 in Davos, it is time for “members of the most privileged class of human beings ever to walk the earth” to back “higher and fairer taxes on millionaires and billionaires and prevent individual and corporate tax avoidance and evasion.” Responsible business leaders should support corporate tax reform, nationally and globally, that will necessarily include higher rates, removing exemptions, and closing down tax havens and other tax loopholes.

Despite the lessons from AIDS, monetizing of intellectual property has brought a system of huge private monopolies, insufficient research into key diseases and prices that a majority of the world can’t afford. Countries will need to use all available flexibility to ensure availability of essential health treatments for all their people, and secure new rules that prioritize collective health over private profit. There needs to be prior international agreement that any vaccines and treatments discovered for COVID-19 will be made available to all countries. The proposal by Costa Rica for a “global patent pool” would allow all technologies designed for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of COVID-19 to be openly available, making it impossible for any one company or country to monopolize them. Developing countries must not be priced out or left standing at the back of the pharma queue.

Leadership is needed in reshaping global cooperation: the COVID-19 crisis has exposed our multilateral system as unequal, outdated and unable to respond to today’s challenges. We will face even greater threats than this pandemic, which only an inclusive and just multilateralism will enable us to overcome.

All of us need all of us

The COVID-19 pandemic is simultaneously a crisis worsening existing inequalities and an opportunity that makes those inequalities visible.

The HIV response proves that only a rights-based approach rooted in valuing everybody equally can enable societies to overcome the existential threat of pandemics. Universal healthcare is not a gift from the haves to the have-nots but a right for all and a shared investment in our common safety and wellbeing.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.