Criminalization

Feature Story

The communities behind Antigua and Barbuda’s decriminalization win

12 July 2022

12 July 2022 12 July 2022Last week Antigua and Barbuda’s High Court struck down laws criminalizing sexual acts between consenting, adult, same sex partners. Orden David, a gay man, brought the case.

In some ways, he’s an unlikely candidate. He describes himself as “private” and “quiet”—characteristics that make him an excellent HIV counsellor and tester. By day he works for the Health Ministry of the very government he challenged. For the past eight years clients have trusted him to treat their interactions with care and confidentiality. He almost seems wired for discretion.

When asked about the personal experiences that compelled him to become the face for a challenge to his country’s “buggery” laws, he’s reluctant to recount them. But the laundry list is included in the judgment.

Slurs.

Insults.

Bullying throughout school.

Photos taken by strangers and posted to social media.

Two unprovoked physical attacks: one on the street at night, another at work.

And most upsetting for Mr David, a string of interactions with police officers who either harassed him or seemed entirely unmotivated to offer the protection afforded to other citizens. Once when he tried reporting a robbery, an officer responded, “Why are you gay?”. Another time police officers neglected to notify him about a court appearance and the case against his assailant was thrown out.

Throughout the Commonwealth Caribbean, homophobic attitudes are not just a matter of personal opinion or conservative religious teaching. In many minds they are sanctioned by states that have retained laws dating back to the 19th century which criminalize same-sex relationships.

A 2014 online survey of men who have sex with men in the Caribbean commissioned by UNAIDS found that within the past month one-third (33%) of respondents had been stared at or intimidated while almost a quarter (23%) experienced verbal abuse. About one in ten (11%) reported being physically assaulted in the past five years.

Mr David has a unique perspective on how these dynamics—intolerant social attitudes, homophobic abuse, punitive laws and a lack of legal protection—affect the LGBT community’s access to HIV services. He’s had clients refuse to accept calls or show up to treatment after testing positive.

“Because the country is so small and everybody knows everybody, there is a lot of fear,” he explains. (Antigua and Barbuda has a population of 98,000 people.) “People are scared to access services on their own or even pick up their medicines. I normally pick up stuff for people. At the Ministry of Health we distribute condoms and lubricants for free, and the test is free. The access is good, there is no doubt. But persons are sometimes not brave enough.”

The second claimant in the case was the non-governmental organization Women against Rape (WAR). For many years WAR has provided counselling to people from key and vulnerable communities. The group submitted that members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) population were often fearful of being treated in a hostile manner by healthcare workers, resulting in some avoiding HIV testing, treatment and follow-up care.

“HIV has been branded by society as a disease linked to immoral behaviour,” said Alexandrina Wong, WAR’s Executive Director. “Coupled with the stigma entrenched in our laws and policies, this creates a hostile environment for vulnerable populations, especially men who have sex with men, sex workers and transgender people who have already been pushed to the very margins of society. There is every indication that this contributes to the transmission of HIV.”

A 2021 round-up of research on human rights, HIV and men who have sex with men (MSM) by UNAIDS found worse outcomes across the testing and treatment cascade for LGBT people in countries where they are criminalized. Those living in states with the most repressive laws were three times less likely to be aware of their HIV status than counterparts in other places. And MSM in countries with criminal penalties were found to be between two to five times more likely to be living with HIV as those in countries without punitive laws.

The Antigua and Barbuda case was one from a five-country litigation strategy coordinated by the Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality (ECADE). ECADE Executive Director, Kenita Placide, reflected that the initiative started in 2015 when activists gathered to discuss how punitive laws in the Caribbean increased stigma, discrimination and even violence.

“The process of litigation is important, as it underscores how these laws contribute to the stigmatisation of LGBT people, how they legitimise hate speech, discrimination and violence and tear at the fabric of our society. Our governments have sworn to protect and uphold the rights of all and act in a manner that promotes the prosperity and well-being of all. This judgment is in keeping with this commitment,” they said.

The partners in Antigua and Barbuda know law reform isn’t a magic bullet. But they consider it an important step forward toward ending the inequalities that drive HIV, injustice and lack of access to opportunities.

“We now have safety under the law. We have to look at how we get members of the family and church to see people as equal regardless of sexual orientation, class, creed or anything like that. The judgement paves the way for higher levels of acceptance for inclusion and diversity,” Ms Wong ended.

Region/country

Feature Story

Jamaican parliamentarians committed to ending discrimination

25 November 2021

25 November 2021 25 November 2021Members of parliament have reaffirmed their commitment to tackle all forms of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in Jamaica and to help enhance efforts to create an enabling environment for people living with and affected by HIV.

At a meeting co-hosted by UNAIDS and Juliet Cuthbert-Flynn, the Minister of State for Health and Wellness and Chair of the country’s Partnership for Action to Eliminate all Forms of HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination, members of parliament, from both the ruling and opposition parties, came together to review evidence on stigma and discrimination in Jamaica and its impact on health outcomes and to craft a way forward in which their role as lawmakers can contribute to eliminating stigma, discrimination and violence.

Jamaica’s legal landscape poses substantial barriers for people living with and affected by HIV to access health services. For example, same-sex sexual relations are criminalized in Jamaica, which continues to represent a considerable deterrent for marginalized communities. Moreover, the country lacks general legislation against discrimination, a national human rights institute and a gender recognition law that could provide further protection for transgender and gender non-conforming people in Jamaica.

Harmful laws, policies and generalized stigma and discrimination against people living with and affected by HIV have a profound negative effect on people’s health outcomes and life prospects. The most recent Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Behaviour Survey and the People Living with HIV Stigma Index showed that only approximately 12% of the general population have accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV, while close to 60% of people living with HIV have feelings of self-stigma. A 2019 study about the economic survivability of transgender and gender non-conforming communities in Jamaica found that experiences of workplace stigma and discrimination were widespread, with about 60% of survey respondents declaring such incidents. Furthermore, 71% of respondents felt that transgender and gender non-conforming people had a harder time getting jobs than cisgender people. Another study suggests that approximately 20% of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Jamaica have been homeless at some point of their lives.

In view of these pending challenges in the country’s HIV and human rights response, members of parliament explored creating a working group tasked with performing periodic reviews of relevant data, supporting the enactment of protective legislation, challenging harmful laws and policies and hosting permanent dialogues with communities of people living with and affected by HIV.

“We have a lot of work to do to ensure that all Jamaicans enjoy the full respect, protection and promotion of their rights. This meeting and its outcomes are a small step to achieving that goal, but a step that certainly is pointing us to the right direction on the role that members of parliament should play to end discrimination,” said Ms Cuthbert-Flynn.

These efforts, which aim to tackle deeply rooted misconceptions in society, require strong partnerships. As stated by Morais Guy, the Opposition Spokesperson on Health, who co-chaired the meeting, “The enhancement of people’s rights and collective efforts to ensure that every Jamaican can live a life free from stigma, discrimination and violence is not an issue of only one person, one entity or one political party. It is the business of all of us, to work in partnership for the dignity of all Jamaicans.”

Members of parliament also discussed some of the challenges that they face as legislators to perform their duties, and the contributions that UNAIDS can make in facilitating a more efficient, effective and transparent law-making process in parliament. Moreover, options to mobilize and engage citizens at the community level to challenge stigma were also discussed in response to the critical need of raising more awareness, tolerance and respect towards people living with and affected by HIV.

“We are proud to partner with members of parliament to tackle stigma and discrimination in Jamaica and to provide all of the evidence, instruments and support that we can mobilize to leverage their role as allies and critical influencers in the future of the country,” said Manoela Manova, the UNAIDS Country Director for Jamaica.

Region/country

Related

Opinion

Forty years of AIDS: Equality remains central to quelling a still-potent epidemic

01 December 2021

01 December 2021 01 December 2021by Edwin Cameron

On 1 December, we mark World AIDS Day.

This year marks a sombre anniversary. On 5 June 2021, it was forty years since disturbingly unexplained cases of illness and death – later called AIDS – were first officially tabulated. These four decades have yielded enormous medical and scientific progress – but too many deaths and far too much stigma remain very much with us.

Too many still elude testing, or die in silence and shame; treatment does not reach all who need it – and inequality and discrimination impede our global response.

Today, I am able to pen this because life unexpectedly afforded me survival from AIDS. Twenty four years ago, I started on life-saving antiretroviral treatment – enabling me to bear witness to how discriminatory laws and policies damage those this fearsome epidemic imperils. Let me explain.

Around Easter 1985, in my early 30s and setting out on my career, I became infected with HIV. In those terrible years, no treatment existed: HIV meant certain death. Stigma and fear choked all who had or were suspected of having HIV or AIDS.

Like many others, I kept my HIV a secret. I hoped against hope that I would escape the spectre of death. No. Twelve years later, AIDS felled my body. With the certainty of death impending, I became terribly ill.

But my privileges gave me access to treatment and care. I had loving family and friends, and my job as a judge to return to. With early access to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, I survived.

In 1999, I spoke publicly about living with HIV. I explained that ARVs had saved me from certain death – but that millions more in Africa were denied them.

Today, I remain one of the only people holding public office in Africa to speak publicly about being gay and about living with HIV. I say this not to claim credit, but because so much shame, fear, ignorance and discrimination still silence too many in too many places.

From my life, in my own deepest being, I know the power of stigma, discrimination, hatred and exclusion.

And, after twenty-five years as a judge, I have been witness to three facts. First, the destructive power of stigma and shame. Second, the damage punitive and discriminatory laws inflict on public health responses. Finally, how insufficient legal protections and inadequate legal remedies make the cruel load of HIV/AIDS infinitely worse.

Why equality is at the heart of the response to HIV/AIDS

Some 37.7 million people globally are living with HIV. For most of us, heartening developments have alleviated the burdens of death and illness and shame. Today, we can fulfil our aspiration to reach the 90-90-90 target (90% of those with HIV must know their status, 90% of them to access treatment, and 90% of those to attain viral suppression).

In Africa, the epidemic however has a particular poignancy. Two-thirds of HIV cases are in Sub-Saharan Africa – and here young women make up 63% of new HIV infections.

As acutely, key populations (sex workers, LGBTQI+ people, drug users, those incarcerated, men who have sex with men) account for 65% of new HIV infections worldwide.

Given these striking facts, the new strategy the UN body fighting to mitigate the epidemic – UNAIDS – announced was welcome. This highlights how inequalities exacerbate AIDS. Ending them is therefore at the core of UNAIDS’s new approach.

A rights-based approach is right. It illuminates how human rights are all interconnected. The AIDS epidemic vividly instances this: the right to health cannot, in though or practice, be disconnected from the right to equality.

The lesson is clear: to overcome AIDS by 2030, we must achieve greater equality for all.

The good news is that protecting and respecting rights works in mitigating AIDS. Evidence from UNAIDS powerfully shows how “inequalities fuel the HIV epidemic and block progress towards ending AIDS.” As The Lancet rightly notes: “The success of the HIV response is predicated on equality – not only equality in access to prevention, care, and treatment … but also equality under the law.”

Human rights programs and sensible law reforms reduce stigma and discrimination. Yet far too little funding and effort is channeled here. The result is plain – in far too many societies, stigma sits as a dark burden on the backs of those living with and at risk of HIV and AIDS; discrimination permeates the societies and their laws – and repeal of misplaced, punitive laws is agonizingly slow.

No to punitive and discriminatory laws

Punitive and discriminatory laws target key populations most at risk of HIV/AIDS. They hit on peoples’ sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, drug use, and sex work.

Thus, too many countries still criminalize LGBTQI+ persons. And transgender women are at enormously higher risk of contracting HIV.

And no one suffers discrimination solely on only one ground. The poisonous perils of discrimination mingle in a multiplicity of hostile grounds – what is rightly called “intersectionality”. A sex worker is attacked for their sexuality, gender, socio-economic status, and HIV status. The disquieting result: sex workers, have a 26 times higher risk of contracting HIV.

In all this, the brutal force of the criminal law clenches the throat of good AIDS work. It intensifies inequalities, unfairness and exclusions.

The point is this: criminalizing people living with HIV and punishing key populations undermines prevention efforts. It reduces uptake of services. And it can increase HIV infections.

These punitive laws do not merely “leave people behind”. They actively shove them out. They increase fear and stigma – and in turn push those most at risk away from health services and social protections.

As UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima, powerfully recounted, “Stigma killed my brother, he was HIV positive and would be living today but he was afraid to go to the clinic to fetch his ARVs because people he knew would find him there and would judge him.” Her conclusion? “We have to fight stigma and discrimination, they kill.”

Additional knock-on effects harm our societies. Discrimination seeps into data and evidence collecting, where criminalized and stigmatized populations are often under-represented and omitted.

This reflects their day-to-day reality: their experience of an extreme form of stigma – being negated, invisible, wiped out.

This negation is profoundly harmful. It means that we do not know whether services are accessible and acceptable. It means important information may not be provided. It means violence and discrimination against invisible populations remain unknown, unaddressed.

So, we must ask: How can you remove barriers to access services if you do not even see the persons they are crushing? What can we do?

At least one answer: We can help create enabling, empowering, safe-guarding legal environments.

An enabling legal environment

The response to AIDS is linked to democratic values and functioning legal systems. The rule of law, freedom of expression, freedom to protest, and other basic human rights matter.

Creating an enabling legal environment is a critical step. It means we employ the law to empower rather than oppress. It means scrapping pointlessly punitive criminal laws. It means achieving equality before the law.

Access to justice, the demand for law reform, awareness as well as education campaigns and vibrant civil society activism, embracing key populations, are pivotal. These foster beneficial change and help ensure accountability for human rights violations.

The last forty years showed us this. Brave, principled, outspoken activists, from ACT UP in New York and the Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa, secured life-saving gains in treatment for AIDS. The activists’ struggle was for justice and for finding the most effective response to AIDS. In South Africa, the activists challenged President Mbeki’s denialist government in the highest Court – which ordered him to start providing ARVs.

For them, as it was for me, and still is for too many today, the battle was about life versus death, wellness versus sickness, science versus harmful myths, discrimination versus justice and equality – and about how fair practices make sound public health sense and save lives.

The new UNAIDS strategy embraces this history. It seeks to ensure access to justice and accountability for people living with or affected by HIV and key populations. Rightly, it calls for: increased collaboration among key stakeholders, for supporting legal literacy programs, and for increased access to legal help. From the international community, it also provides for substantial commitment, greater investments, and strategic diplomacy.

The Covid-19 pandemic has not alleviated these goals – its impact on inequality has made them more pressing. Anti-infection lockdowns led to HIV and AIDS service disruptions (healthcare facilities were closed or resources were reallocated to Covid-19 or there were shortages of ARVs).

On the other hand, lessons have been learnt, and mRNA technology could speed up the development of AIDS vaccines.

Though there is still no cure, AIDS is no longer a death sentence. Twenty four years after taking my first ARVs, I am living a vibrant, joyful life. Our challenge lies within ourselves, and our societies: it is to overcome fear, discrimination and stigma to ensure life-saving treatments and messages are equally and equitably accessible.

Ending AIDS by 2030 is a realistic goal. But to achieve it, we must respect, protect and fulfil the basic rights of those living with and at risk of HIV. We must embrace democratic aspirations, place key populations at the center of our response, provide resources to reduce inequalities as well as inequities, and foster legal environments that enable us to end AIDS.

These harsh last forty years have shown us this: with enough support, science, focus and love, we can end AIDS.

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Documents

HIV and stigma and discrimination — Human rights fact sheet series 2021

02 June 2021

The 2021-2026 Global AIDS Strategy has bold and critical new targets on realizing human rights, reducing stigma, discrimination and violence and removing harmful punitive laws as a pathway to ending inequalities and ultimately ending AIDS. To aid in the scale up of interventions to remove these societal barriers, UNAIDS has produced a series of fact sheets on human rights in various areas, highlighting the critical need to scale up action on rights. They are a series of short, easy to digest and accessible documents outlining the latest epidemiology, the evidence of the impact of human rights interventions, the latest targets, and international guidelines, recommendations and human rights obligations relating to each topic. Fact sheets: HIV criminalization, HIV and people who use drugs, HIV and gay men and who have sex with other men, HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people, HIV and sex work, HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings and HIV and stigma and discrimination. This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Global celebrities unite behind UNAIDS’ call for world leaders to “take the rights path to end AIDS”

Global celebrities unite behind UNAIDS’ call for world leaders to “take the rights path to end AIDS”

01 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

Documents

HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings — Human rights fact sheet series 2021

02 June 2021

The 2021-2026 Global AIDS Strategy has bold and critical new targets on realizing human rights, reducing stigma, discrimination and violence and removing harmful punitive laws as a pathway to ending inequalities and ultimately ending AIDS. To aid in the scale up of interventions to remove these societal barriers, UNAIDS has produced a series of fact sheets on human rights in various areas, highlighting the critical need to scale up action on rights. They are a series of short, easy to digest and accessible documents outlining the latest epidemiology, the evidence of the impact of human rights interventions, the latest targets, and international guidelines, recommendations and human rights obligations relating to each topic. Fact sheets: HIV criminalization, HIV and people who use drugs, HIV and gay men and who have sex with other men, HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people, HIV and sex work, HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings and HIV and stigma and discrimination. This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

21 October 2024

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

01 October 2024

Documents

HIV and sex work — Human rights fact sheet series 2021

02 June 2021

The 2021-2026 Global AIDS Strategy has bold and critical new targets on realizing human rights, reducing stigma, discrimination and violence and removing harmful punitive laws as a pathway to ending inequalities and ultimately ending AIDS. To aid in the scale up of interventions to remove these societal barriers, UNAIDS has produced a series of fact sheets on human rights in various areas, highlighting the critical need to scale up action on rights. They are a series of short, easy to digest and accessible documents outlining the latest epidemiology, the evidence of the impact of human rights interventions, the latest targets, and international guidelines, recommendations and human rights obligations relating to each topic. Fact sheets: HIV criminalization, HIV and people who use drugs, HIV and gay men and who have sex with other men, HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people, HIV and sex work, HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings and HIV and stigma and discrimination. This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

21 October 2024

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

01 October 2024

Documents

HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people — Human rights fact sheet series 2021

02 June 2021

The 2021-2026 Global AIDS Strategy has bold and critical new targets on realizing human rights, reducing stigma, discrimination and violence and removing harmful punitive laws as a pathway to ending inequalities and ultimately ending AIDS. To aid in the scale up of interventions to remove these societal barriers, UNAIDS has produced a series of fact sheets on human rights in various areas, highlighting the critical need to scale up action on rights. They are a series of short, easy to digest and accessible documents outlining the latest epidemiology, the evidence of the impact of human rights interventions, the latest targets, and international guidelines, recommendations and human rights obligations relating to each topic. Fact sheets: HIV criminalization, HIV and people who use drugs, HIV and gay men and who have sex with other men, HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people, HIV and sex work, HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings and HIV and stigma and discrimination. This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

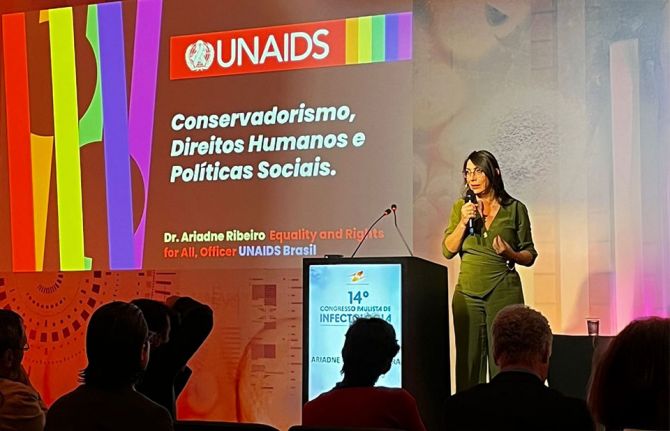

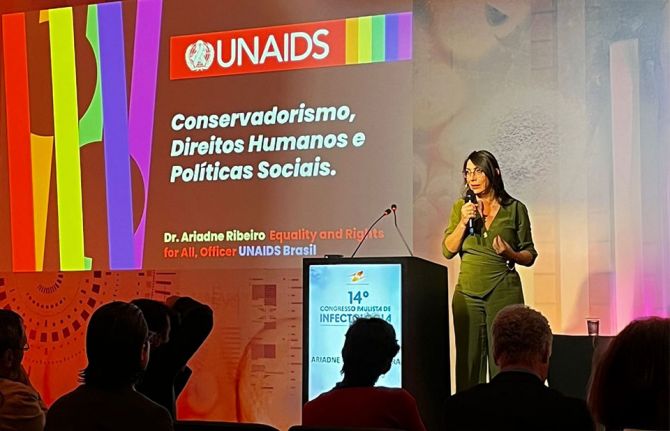

Upholding dignity for everyone: Ariadne Ribeiro Ferreira

Upholding dignity for everyone: Ariadne Ribeiro Ferreira

21 November 2024

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

21 October 2024

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

01 October 2024