Health systems strengthening

Feature Story

Félix Tshisekedi, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 2021 African Union Chair, calls on his peers to learn from HIV and strengthen health systems

15 February 2021

15 February 2021 15 February 2021The 34th Ordinary Assembly of the African Union Heads of States and Government was held virtually on 6 and 7 February 2021.

The President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and new Chair of the African Union, Félix Tshisekedi, pictured above, urged Member States not to forget devastating global epidemics, such as malaria and AIDS, and learn from them to strengthen health systems, including the reinforcement of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Leveraging the experiences we have gained in the fight against adversity and our ability to adapt, we should not give up. Let us not forget other pandemics, often more deadly, that are still affecting the continent, like malaria and HIV,” said the President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The assembly recognized the African Union’s role in mounting a united, innovative and strong partnership among Member States to address the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a significant economic impact on Africa and further weakened its health systems.

Heads of states committed to sustaining efforts to curb the spread of the virus and mitigate its socioeconomic impact by using the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement and to implement a coordinated vaccination programme through the Africa Vaccine Acquisition Task Team to ensure that no country is left behind.

“In responding to the pandemic, we have been at the forefront of innovation. We established the groundbreaking Africa Medical Supplies Platform to assist African Union Member States to access affordable medical supplies and equipment,” said the President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, pictured above.

The President of South Africa commended heads of states for their extraordinary and decisive leadership in tackling the COVID-19 crisis. He expressed dismay at the increase in violence against women and called on the continental body to prioritize women’s economic empowerment and develop a convention to promote, protect and fulfil women’s rights. He called on Member States to ratify International Labour Organization Convention No. 190 on eliminating harassment and violence in the world of work.

Aside from the African Union Chair’s handover from South Africa to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the two-day assembly marked critical decisions on the implementation of the African Union’s institutional reform, including its Commission, and the election of four new commissioners. Moussa Faki Mahamat was re-elected as the African Union Commission Chairperson for a second four-year term and newly elected Monique Nsanzabaganwa, the first female in the history of the Commission, as his deputy.

“I congratulate the President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Félix Tshisekedi, for taking the reins as the Chair of the African Union for 2021 and commend him for calling on his peers to sustain efforts in the AIDS response and strengthen health systems in Africa while we are still facing the COVID-19 pandemic. I reaffirm UNAIDS’ support to the African Union. Saving lives, tackling inequalities and advancing universal health care are lessons learned from AIDS to address current and future pandemics successfully,” said Clémence Aissatou Habi Baré, Director of the UNAIDS Liaison Office to the African Union and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Related

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

24 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

20 February 2025

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

19 February 2025

Press Statement

UNAIDS calls for rights-based and people-centred universal health coverage

12 December 2020 12 December 2020GENEVA, 12 December 2020—The world is only 10 years away from the deadline for the universal health coverage target of the Sustainable Development Goals. Only 10 years away from when everyone should have access to quality essential health services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines. But that target seems as far away as ever. In 2017, less than half of the world’s people were covered by essential health services, and if current trends continue it is estimated that only 60% of the global population will enjoy universal health coverage by 2030.

On Universal Health Coverage Day, UNAIDS is calling for the world to meet its obligation— universal health coverage, based on human rights and with people at the centre.

“Health for all: protect everyone” is the theme for this year’s Universal Health Coverage Day, making it clear that health is a fundamental human right.

“It’s a disgrace that inequalities are still impacting the ability of people to access health care,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director. “Health is a human right, but it is so often denied, especially to the most vulnerable, the marginalized and the criminalized.”

Someone’s socioeconomic status, gender, age, sexual orientation, citizenship or race can affect their ability to access health services. Like the HIV response, equality lies at the heart of universal health coverage and progressing towards universal health coverage means progressing towards equity, social inclusion and cohesion. A rights-based and people-centred approach to universal health coverage can help to ensure equitable health for all.

COVID-19 has shown that public health systems have been neglected in many countries around the world. In order to promote health and well-being, countries need to invest in the core functions of health systems, including public health, as common goods for health.

“Money should never determine someone’s access to health,” added Ms Byanyima. “No one should be pushed into poverty by paying for health services. User fees must be abolished and health for all paid for from public funds.”

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the global AIDS response was off track, in part because of a long-term underinvestment in health systems. Universal health coverage and the end of AIDS cannot be achieved and sustained without resilient and functioning health systems that can respond to the needs of everyone, without stigma and discrimination.

The HIV response has shown that communities make the difference. During the COVID-19 pandemic, community-led organizations, including communities of people living with HIV, around the world have mobilized to protect the vulnerable, working with governments to keep essential services going.

Communities have campaigned for multimonth dispensing of HIV treatment, organized home deliveries of medicines and provided financial assistance, food and shelter to at-risk groups. Communities are part of systems for health and are fundamental to attaining universal health coverage. They must be better recognized and supported for their leadership, their innovation and their immense contribution towards health for all.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Contact

UNAIDS GenevaSophie Barton-Knott

tel. +41 79 514 68 96

bartonknotts@unaids.org

UNAIDS Media

tel. +41 22 791 4237

communications@unaids.org

Our work

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)

Feature Story

Study shows how COVID-19 is impacting access to HIV care in the Russian Federation

27 November 2020

27 November 2020 27 November 2020A new study shows the negative impact that the COVID-19 pandemic is having on access to HIV care in the Russian Federation and shows that people living with HIV in the country are more susceptible to COVID-19 but less likely to seek testing or treatment.

More than a third of people living with HIV who were surveyed reported some impact on HIV services, including about 4% who reported that they had missed taking antiretroviral therapy because they could not get the medicine and nearly 9% who reported that they had missed taking medicine for tuberculosis prevention. However, the majority of respondents (about 70% of people living with HIV) did not experience problems obtaining antiretroviral therapy and about 22% reported that antiretroviral medicines were delivered to their home. More than 900 respondents from 68 regions of the Russian Federation, including people living with HIV and those who are not, were reached by the study.

“This study answers some of the most important questions about the impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV in our country,” said Natalya Ladnaya, Principal Investigator and Senior Researcher at the Central Research Institute of Epidemiology of the Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor).

According to Ms Ladnaya, the study confirmed that it is crucial for people living with HIV to protect themselves against the new coronavirus. The authors of the study also note the need to provide uninterrupted HIV treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Encouraging results were obtained on how the pandemic affected access to HIV treatment—many specialized institutions have been able to adapt to the new reality,” said Alexey Mikhailov, Head of the Monitoring Department of the Treatment Preparedness Coalition, who took part in the study.

According to the study, the number of people living with HIV with COVID-19 markers was four times higher than that of HIV-negative respondents. At the same time, they were half as likely, compared with HIV-negative respondents, to be tested for coronavirus infection and were less likely to seek medical help, even if they had symptoms.

The majority of respondents with HIV and COVID-19 coinfection had a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 due to the significant number of local cases of COVID-19 and the low level of use of personal protective measures, as well as an underestimation of the real personal risk of COVID-19 disease.

Although more than two thirds of the study participants were women, among people living with HIV and having had COVID-19 the majority of respondents were men who had lived with HIV for more than 10 years.

The authors of the study point to the need for further investigation into the causes of the increased incidence of COVID-19 and the low demand for medical care to treat the symptoms of COVID-19 among people living with HIV.

“The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect all areas of our lives. We need to closely monitor the colliding pandemics of COVID-19 and HIV and provide support so as not to lose the gains in the response to HIV that have been achieved,” said Alexander Goliusov, Director, a.i., UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The study was conducted by the Central Research Institute of Epidemiology of Rospotrebnadzor together with the Treatment Preparedness Coalition with the support of UNAIDS and Rospotrebnadzor.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Press Release

UNAIDS calls on countries to step up global action and proposes bold new HIV targets for 2025

26 November 2020 26 November 2020As COVID-19 pushes the AIDS response even further off track and the 2020 targets are missed, UNAIDS is urging countries to learn from the lessons of underinvesting in health and to step up global action to end AIDS and other pandemics

GENEVA, 26 November 2020—In a new report, Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the centre, UNAIDS is calling on countries to make far greater investments in global pandemic responses and adopt a new set of bold, ambitious but achievable HIV targets. If those targets are met, the world will be back on track to ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

The global AIDS response was off track before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, but the rapid spread of the coronavirus has created additional setbacks. Modelling of the pandemic’s long-term impact on the HIV response shows that there could be an estimated 123 000 to 293 000 additional new HIV infections and 69 000 to 148 000 additional AIDS-related deaths between 2020 and 2022.

“The collective failure to invest sufficiently in comprehensive, rights-based, people-centred HIV responses has come at a terrible price,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “Implementing just the most politically palatable programmes will not turn the tide against COVID-19 or end AIDS. To get the global response back on track will require putting people first and tackling the inequalities on which epidemics thrive.”

New targets for getting back on track

Although some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Botswana and Eswatini, have done remarkably well and have achieved or even exceeded the targets set for 2020, many more countries are falling way behind. The high-performing countries have created a path for others to follow. UNAIDS has worked with its partners to distil those lessons into a set of proposed targets for 2025 that take a people-centred approach.

The targets focus on a high coverage of HIV and reproductive and sexual health services together with the removal of punitive laws and policies and on reducing stigma and discrimination. They put people at the centre, especially the people most at risk and the marginalized—young women and girls, adolescents, sex workers, transgender people, people who inject drugs and gay men and other men who have sex with men.

New HIV service delivery targets aim at achieving a 95% coverage for each sub-population of people living with and at increased risk of HIV. By taking a person-centred approach and focusing on the hotspots, countries will be better placed to control their epidemics.

The 2025 targets also require ensuring a conducive environment for an effective HIV response and include ambitious antidiscrimination targets so that less than 10% of countries have punitive laws and policies, less than 10% of people living with and affected by HIV experience stigma and discrimination and less than 10% experience gender inequality and violence.

Prevailing against pandemics

Insufficient investment and action on HIV and other pandemics left the world exposed to COVID-19. Had health systems and social safety nets been even stronger, the world would have been better positioned to slow the spread of COVID-19 and withstand its impact. COVID-19 has shown that investments in health save lives but also provide a foundation for strong economies. Health and HIV programmes must be fully funded, both in times of plenty and in times of economic crisis.

“No country can defeat these pandemics on its own,” said Ms Byanyima. “A challenge of this magnitude can only be defeated by forging global solidarity, accepting a shared responsibility and mobilizing a response that leaves no one behind. We can do this by sharing the load and working together.”

There are bright spots: the leadership, infrastructure and lessons of the HIV response are being leveraged to fight COVID-19. The HIV response has helped to ensure the continuity of services in the face of extraordinary challenges. The response by communities against COVID-19 has shown what can be achieved by working together.

In addition, the world must learn from the mistakes of the HIV response, when millions in developing countries died waiting for treatment. Even today, more than 12 million people still do not have access to HIV treatment and 1.7 million people became infected with HIV in 2019 because they did not have access to essential HIV services.

Everyone has a right to health, which is why UNAIDS has been a leading advocate for a People’s Vaccine against COVID-19. Promising COVID-19 vaccines are emerging, but we must ensure that they are not the privilege of the rich. Therefore, UNAIDS and partners are calling on pharmaceutical companies to openly share their technology and know-how and to wave their intellectual property rights so that the world can produce successful vaccines at the huge scale and speed required to protect everyone.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Contact

UNAIDS GenevaSophie Barton-Knott

tel. +41 79 514 68 96

bartonknotts@unaids.org

UNAIDS Media

tel. +41 22 791 4237

communications@unaids.org

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)

Press Release

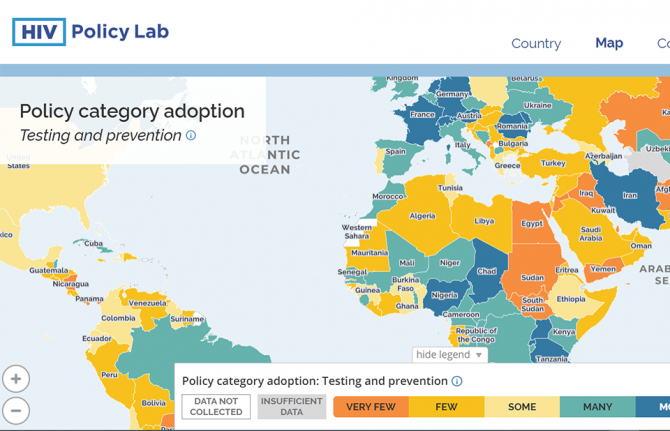

New HIV Policy Lab uses law and policy data in the HIV response

29 September 2020 29 September 2020WASHINGTON, D.C./GENEVA, 29 September 2020—Despite decades of scientific advance in the HIV response, progress remains uneven, with some countries rapidly reducing AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections and others seeing increasing epidemics. Laws and policies are driving a significant part of that divergence.

Launched today, the HIV Policy Lab is a unique initiative to gather and monitor HIV-related laws and policies around the world.

“Laws and policies are life or death issues when it comes to HIV. They can ensure access to the best that science has to offer and help people to realize their rights and live well, or they can be barriers to people’s well-being. Like anything that matters, we need to measure the policy environment and work to transform it as a key part of the AIDS response,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director.

The HIV Policy Lab is a data visualization and comparison tool that tracks national policy across 33 different indicators in 194 countries around the world, giving a measure of the policy environment. The goal is to improve transparency, the ability to understand and use the information easily and the ability to compare countries, supporting governments to learn from their neighbours, civil society to increase accountability and researchers to study the impact of laws and policies on the HIV pandemic.

According to Matthew Kavanagh, Director of the Global Health Policy & Politics Initiative at Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute, “Policy is how governments take science to scale. If we want to improve how policy is used to improve health outcomes, it is essential to monitor and evaluate the policies that comprise it.”

“Reducing stigma and making care easier to access are fundamental for improving the lives of people living with HIV—and those are all consequences of policy choices. Tracking these choices is a key tool for improving them, and ensuring justice and equity for people living with HIV,” said Rico Gustav, Executive Director of the Global Network of People Living with HIV.

The HIV Policy Lab draws information from the National Commitments and Policy Instrument, legal documents, government reports and independent analyses to create data sets that can be compared across countries and across issues. The goal of the HIV Policy Lab is to help identify and address the gaps between evidence and policy and to build accountability for a more inclusive, effective, rights-based and science-based HIV policy response.

The HIV Policy Lab is a collaboration between Georgetown University and the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, UNAIDS, the Global Network of People Living with HIV and Talus Analytics.

About the Georgetown University O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law

The O’Neill Institute, housed at Georgetown University, was established to create innovative solutions to the most pressing national and international health concerns, with the essential vision that the law has been, and will remain, a fundamental tool for solving critical health problems. The Georgetown University Department of International Health is home to scholarship in public health, economics, political science, and medicine. Georgetown’s Global Health Initiative serves as a university-wide platform for developing concrete solutions to the health challenges facing families and communities throughout the world. Read more at oneillinstitute.org and connect with us on Twitter and Facebook.

About UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

About GNP+

GNP+ is the global network for and by people living with HIV. GNP+ works to improve the quality of life of all people living with HIV. GNP+ advocates for, and supports fair and equal access to treatment, care and support services for people living with HIV around the world. Learn more at gnpplus.net and connect with GNP+ on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Contact

O’Neill InstituteLauren Dueck

Lauren.Dueck@Georgetown.edu

UNAIDS

Sophie Barton-Knott

bartonknotts@unaids.org

GNP+

Lesego Tlhwale

ltlhwale@gnpplus.net

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)

Feature Story

Somalia: building a stronger primary health care system

15 September 2020

15 September 2020 15 September 2020This story was first published by WHO

In the first year of the Stronger Collaboration, Better Health: The Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (GAP), 12 signatory agencies have engaged with several countries to help them achieve their major health priorities. The initial focus has been on strengthening primary health care and sustainable financing for health. Somalia is one of the countries where progress under the GAP is most advanced and where its added value has been most clearly demonstrated.

The Somalia country Director and Representative of the World Food Programme, Dr Cesar Arroyo underlined the vital importance of the GAP – through cementing collaboration among the 12 agencies: “The GAP initiative marks a crucial step towards solving health-related challenges in Somalia and offers us an opportunity to strengthen our partnerships across the humanitarian community thereby enhancing operational efficiency, particularly within the COVID-19 context and beyond”.

Three decades of civil war and instability have weakened Somalia’s health system and contributed to it having some of the lowest health indicators in the world. The situation varies from region to region but between 26-70% of Somalia’s 15 million people live in poverty and an estimated 2.6 million people have been internally displaced.

But the Government is committed to using current opportunities to strengthen health and social development. These include implementation of Somali National Development Plan for 2019–2024 and the Somali Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Roadmap, launched in September 2019.

Both plans identify primary health care as the main approach to improving health outcomes in the country. Primary health care provides whole-person care for most health needs throughout the lifespan, ensuring that everyone can receive comprehensive care ─ ranging from health promotion and prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care ─ as close as possible to where they live.

Working together, the Government of Somalia, GAP agencies and multilateral and bilateral partners have identified 5 priorities for enhanced collaboration to accelerate progress towards UHC.

Says Monique Vledder, Head of Secretariat for the Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents: “The launch of the Global Action Plan has helped accelerate momentum across global health agencies to align their support to country partners. In Somalia, the GFF has brought the spirit of the GAP from the global to the country level, convening partners across the federal and local governments, Somaliland, UN agencies, donors and civil society to establish the Health Sector Coordination Committee. Country stakeholders and GAP agencies are now building consensus around a priority package of essential services and critical health system reforms”.

Establishment of a health coordination mechanism

Efforts are underway to set up a coordination mechanism for all health partners to strengthen primary health care and fill gaps in services at the district level, building consensus around a priority package of essential services and critical health system reforms and mapping the availability of services and health workers.

Improving access to a package of high-quality essential health services

The country’s health services package is being updated with support from GAP agencies and other partners, with a focus on prevention and community-based components, communicable and noncommunicable diseases, and mental health.

Strengthening emergency preparedness and response through UHC

Somalia is prone to emergencies from natural disasters and disease outbreaks and is now responding to COVID-19. GAP agencies are exploring opportunities to support the finalization and implementation of components of a National Action Plan for Health Security, which includes strengthening of laboratory and early warning systems and ensuring that a package of essential health services and key commodities are effectively delivered in humanitarian settings.

Strengthening the role and capacity of the Ministry of Health

This is essential to address fragmented health service delivery and funding arrangements; improve institutional capacity for policy-making, regulation, coordination, planning, management and contracting; and use of data in decision-making.

Harnessing the private sector for UHC

Private health services and the pharmaceutical sector are largely unregulated in Somalia but could contribute to improving access and achieving UHC. GAP agencies are exploring opportunities to support the development and operationalization of a strategy for the private health sector, to assess its current role in service delivery and implementation of regulatory frameworks and contracting mechanisms.

“GAP provides us an opportunity to accelerate progress in achieving universal health coverage in Somalia through coordinated action and alignment with development partners and UN agencies. More than ever, we now need to push this agenda as we support the health systems of Somalia recover stronger and better from the COVID-19 pandemic“, said WHO Country Representative in Somalia, Dr Mamunur Malik.

“Our collective engagement in improving access to care for women, children, and other vulnerable groups will be decisive in improving health and well being in the country. Through an integrated, coordinated and collaborative approach such as the GAP, we can also build the required capacity of national and local health authorities to deliver not only cost-effective health interventions using a primary healthcare approach, but also monitor and track porgress of the health-related indicators of sustainable development goal in the country", he added.

Although there are many health and social challenges in Somalia, the GAP is leveraging emerging opportunities to strengthen primary health care to support the country in achieving UHC and other health-related SDGs.

To move these efforts forward, GAP agencies are collaborating with the Government to develop an operational plan. They aim to align this with the new funding that a number of agencies are providing for the response to COVID-19, to support the scale-up of primary health care, including implementation of the package of essential health services.

Region/country

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025

Feature Story

Online games fighting HIV stigma and discrimination in the Islamic Republic of Iran

16 June 2020

16 June 2020 16 June 2020The UNAIDS Country Office for the Islamic Republic of Iran and the country’s branch of the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations have been collaborating on new ways of making an impact on the national AIDS response since 2013.

In the past, the collaborations have included public awareness campaigns, educational workshops, field visits and week-long summer schools open to health-care students.

“The summer schools were more than inspiring, they made us confident about our next area of focus: acting against HIV-related stigma and discrimination,” said Aidin Parnia, one of the founders of the summer schools and of the Avecene Consultancy.

Started by people who had attended the summer schools, the Avecene Consultancy was formed to mobilize the accumulated knowledge and experience of the summer schools and to combine them with modern and up-to-date educational developments. The result is the REDXIR educational online platform, which uses games to change the attitude and behaviour of health-care students in order to bring about a future generation of discrimination-free health-care professionals.

Set in an imaginary world where the players are a young group that battles a mysterious enemy that symbolizes HIV-related stigma and discrimination, the goal of REDXIR is to fight back and defeat stigma and discrimination.

The 10 levels of the game are designed to challenge the students’ knowledge of HIV and their attitude and behaviour towards people living with the virus. For example, in the Blood Pressure level of the game, the students have to take the blood pressure of a person living with HIV to show that he or she can do so without discrimination. At higher levels, they should be able to take a blood sugar test and a blood sample for a routine laboratory test.

While some of the levels are performed virtually, others need action to be taken in the real world. For example, in the Do Not Be Silent level, the students must recognize discriminatory posts on social media, post #Zerodiscrimination below at least one of the social media feeds they see and comment on the reason why the content is discriminatory. In the Campaign level, the students participate as trainers in an HIV awareness campaign.

“New generations need new platforms. REDXIR, through its user-friendly approach where students are in direct contact with the target populations, has proved to be an effective way to help eliminate HIV-related stigma and discrimination in health-care settings,” said Parvin Kazerouni, the Head of the HIV Control Department of the Center for Communicable Disease Control of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the National AIDS Manager.

“REDXIR shows how creative and innovative approaches can embrace and support the novel ideas of young people to address issues such as stigma and discrimination,” said Fardad Doroudi, the UNAIDS Country Director for the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The UNAIDS country office provided technical and financial support for REDXIR.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Opinion

Health: providing free health for all, everywhere

20 May 2020

20 May 2020 20 May 2020By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director — First published in World Economic Forum's Insight Report (May 2020)

Recognizing the public-health catastrophe

As we have seen in wealthier countries, economic and social determinants of ill-health are strong predictors of the likelihood of dying from COVID-19. The greatest risk will be for poor people in poor countries who have a much higher burden of existing illness, and of whom hundreds of millions are malnourished or immunocompromised. For the quarter of the world’s urban population who live in slums, and for many refugees and displaced people, it is not possible to socially distance or to constantly wash hands.

Half the world’s people cannot access essential healthcare even in normal times. While Italy has one doctor for every 243 people, Zambia has one doctor for every 10,000 people. Mali has three ventilators per million people. Average health spending in low-income countries is only $41 per person a year, 70 times less than high-income countries.

The pressure the pandemic will place on health facilities will not only affect people with COVID-19 – anyone needing any care will be impacted. This has previously been the case. During the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone there was a 34% increase in maternal mortality and a 24% increase in the stillbirth rate, as fewer women were able to access both pre- and post-natal care.

The International Labour Organization predicts 5 million-25 million jobs will be eradicated, and $860 billion-$3.4 trillion will be lost in labour income. Mass impoverishment will make treatment inaccessible for even more people. Already every year 1 billion people are blocked from healthcare by user fees. This exclusion from vital care won’t only hurt those directly affected – it will put everyone at risk, as a virus can’t be contained if people can’t afford testing or treatment.

Lockdowns without compensation are, at their crudest, forcing millions to choose between danger and hunger. As in many developing country cities, over three quarters of workers are in the informal sector, earning on a daily basis, many who stay in will not have enough to eat and so large numbers will ignore lockdown rules and risk catching the coronavirus.

As we have seen in the AIDS response, governments struggling to contain the crisis may seek scapegoats – migrants, minorities, the socially excluded – making it even harder to reach, test and treat to contain the virus. Donor countries may turn inwards, feeling they can’t afford to help others and, as the presence of COVID-19 anywhere is a threat to people everywhere, this will not only hurt developing countries, it will also exacerbate the challenge in donor countries too.

And yet, amid the pain and fear, the crisis also generates an opportunity for bold, principled, collaborative leadership to change the course of the pandemic and of society.

Seizing the public-health opportunity

Contrary to conventional wisdom that responding to a crisis takes away the capability needed for major health reforms, the biggest steps forward in health have usually happened in response to a major crisis – think of the post-Second World War health systems across Europe and in Japan, or how AIDS and the financial crisis led to universal healthcare in Thailand. Now, in this crisis, leaders across the world have an opportunity to build the health systems that were always needed and which now cannot be delayed any longer.

Universal healthcare

This pandemic has shown that it is in everyone’s interest that people who feel unwell should not check their pocket before they seek help. As the struggle to control an aggressive coronavirus rages on, the case to end user fees in health immediately has become overwhelming.

Free healthcare is not only vital for tackling pandemics: when the Democratic Republic of the Congo instituted free healthcare in 2018 to fight Ebola, healthcare utilization improved across the board with a more than doubling of visits for pneumonia and diarrhoea, and a 20%-50% increase in women giving birth at a clinic – gains that were lost once free healthcare was removed. Free healthcare will also prevent the tragedy of 100 million people driven into extreme poverty by the cost of healthcare every year.

Because COVID-19 has no vaccine yet, all countries will need to be able to limit and hold it. The inevitability of future pandemics makes permanent the need for strong universal health systems in every country in the world.

Publicly funded, cutting-edge medicines and healthcare must be delivered to everyone no matter where they live. To enable universal access, governments must integrate community-led services into public systems. This crisis has also highlighted how our health requires that the health workers who protect and look after us are themselves protected and looked after.

Given the interconnectedness between health and livelihoods, all countries will also need to strengthen social safety nets to enhance resilience. COVID-19 has reminded the world that we need active, accountable, responsible governments to regulate markets, reduce inequality and deliver essential public services. Government is back.

Financing our health

Many developing countries were already facing debt stress leading to cuts in public healthcare. In recognition that worldwide universal healthcare is a global public good, lender governments, international financial institutions and private financial actors need to both extend and go beyond the temporary debt suspensions that have been announced recently. The proposal by the Jubilee Debt Campaign and hundreds of other civil society organizations sets out the kind of ambition required.

Bilateral donors and international financial institutions, including the World Bank, should also offer grants – not loans – to address the social and economic impacts of the pandemic on the poor and most vulnerable groups, including informal sector workers and marginalized populations. Support to developing countries’ ongoing health system costs needs to be stepped up. It would cost approximately $159 billion to double the public health spending of the world’s 85 poorest countries, home to 3.7 billion people. This is less than 8% of the latest US fiscal stimulus alone. It is great to see donor countries using the inspiring and bold language of a new Marshall Plan – but currently pledged contributions are insufficient.

Business leadership

A new kind of leadership is needed from business too; one that recognizes its dependence on healthy societies and on a proper balance between market and state. As President Macron has noted, this pandemic “reveals that some goods and services must be placed outside the rules of the market”. ’The past decade has seen a rapid increase in the commercialization and financialization of healthcare systems across the globe. This must end.

As a group of 175 multimillionaires noted in a public letter released at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2020 in Davos, it is time for “members of the most privileged class of human beings ever to walk the earth” to back “higher and fairer taxes on millionaires and billionaires and prevent individual and corporate tax avoidance and evasion.” Responsible business leaders should support corporate tax reform, nationally and globally, that will necessarily include higher rates, removing exemptions, and closing down tax havens and other tax loopholes.

Despite the lessons from AIDS, monetizing of intellectual property has brought a system of huge private monopolies, insufficient research into key diseases and prices that a majority of the world can’t afford. Countries will need to use all available flexibility to ensure availability of essential health treatments for all their people, and secure new rules that prioritize collective health over private profit. There needs to be prior international agreement that any vaccines and treatments discovered for COVID-19 will be made available to all countries. The proposal by Costa Rica for a “global patent pool” would allow all technologies designed for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of COVID-19 to be openly available, making it impossible for any one company or country to monopolize them. Developing countries must not be priced out or left standing at the back of the pharma queue.

Leadership is needed in reshaping global cooperation: the COVID-19 crisis has exposed our multilateral system as unequal, outdated and unable to respond to today’s challenges. We will face even greater threats than this pandemic, which only an inclusive and just multilateralism will enable us to overcome.

All of us need all of us

The COVID-19 pandemic is simultaneously a crisis worsening existing inequalities and an opportunity that makes those inequalities visible.

The HIV response proves that only a rights-based approach rooted in valuing everybody equally can enable societies to overcome the existential threat of pandemics. Universal healthcare is not a gift from the haves to the have-nots but a right for all and a shared investment in our common safety and wellbeing.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Feature Story

“We are human, so of course it was scary”

13 May 2020

13 May 2020 13 May 2020She is sitting opposite, dressed in a lab coat, and you know that with her you are in safe hands. Her kind eyes convey empathy. Malikakhon Kurbanova, known to all who know her as Malika, has been a nurse at the Kyzyl-Kiya family medical centre in Kyrgyzstan for almost 20 years.

Part of one of 10 pilot multidisciplinary teams specializing in infectious diseases in the country, she has been working with people living with HIV for many years. The multidisciplinary teams were formed by UNAIDS in 2013 and include a specialist in infectious diseases or a family doctor, a nurse and a peer consultant. The teams aim to improve the quality of medical and social services for people living with HIV and their families. During the COVID-19 outbreak they are receiving extra financial help from a Russian technical assistance programme.

Like many health-care workers, Malika has been caught up in the fight against COVID-19. UNAIDS met her recently in her office in the clinic, adjacent to a blossoming apple orchard, and spoke to her about her background and work.

Why did you decide to become a nurse?

When I was a child, I was quite often sick. My mother and I spent a lot of time in hospitals. I always admired the women who wore lab coats and who knew how to inject me painlessly. I knew then that I would become a nurse and help people. When I graduated from school in 1986, I entered the Kyzyl-Kiya medical college and after that, in 1989, I went to work in the health unit in a construction materials plant. That is how my story began. In the beginning of the 2000s the reform of primary health care started and family medical centres were created. I came to work as a nurse and soon joined the infectious diseases unit, where I still work.

You have been working in the COVID-19 response since the very start of the epidemic in the country. Were you frightened?

We do house-to-house visits, helping people with acute respiratory infections. We are human, so of course it was scary—I was afraid about infecting my family.

It is frightening when you are fighting an unknown virus. In the beginning, I did not know what I should tell patients. At the beginning of the pandemic, many people did not believe the truth about COVID-19; some of them accused us of trying to infect them. But over time, people realized that the virus was real, which greatly helped our work.

You work as a nurse in a multidisciplinary team for people living with HIV. How has your work changed since the COVID-19 outbreak started?

To avoid people running out of their medicine and to reduce their possible exposure to people with COVID-19, we are now distributing three-month supplies of antiretroviral therapy, when before we gave out one-month supplies.

We also focus on psychosocial support for people living with HIV. People need mutual support. Our peer consultant calls patients every day and holds online self-help groups via WhatsApp. Thanks to the financial support given to the project, the transport costs of visiting clients and monitoring their adherence to antiretroviral therapy is covered. The most vulnerable people living with HIV have been receiving food packages since April.

What is the hardest part of your work?

We’ve always had difficulties and they are likely to continue, that is the nature of our work! Sometimes I feel like leaving it at behind, but then I realize that this is my life—I am a nurse. It gives me strength when I see that my actions for my patients bring results and people get better.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Documents

Maintaining and prioritizing HIV prevention services in the time of COVID-19

06 May 2020

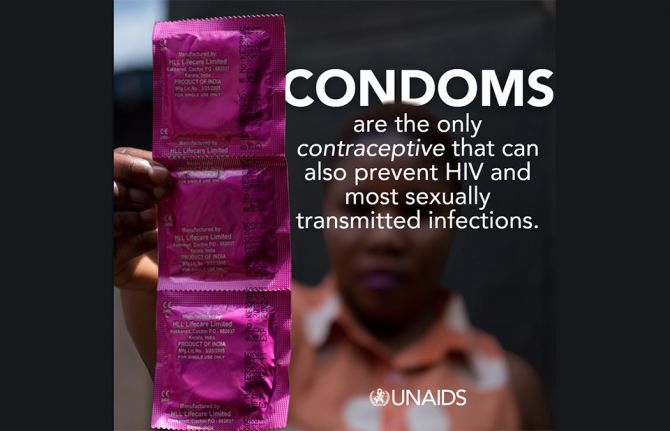

In the time of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), sex and drug use will continue, regardless of physical distancing orders and policies. People who previously met in community gathering venues such as bars and clubs may now meet in different sites, ones that are “hidden” or less accessible. This, in turn, may hinder efforts to reach them with prevention interventions, such as condoms, lubricants, and needle–syringe programmes. With the widespread loss of livelihood and fewer employment opportunities, transactional sex, sex work and sexual exploitation may increase. Anxiety about the pandemic and personal vulnerability also may lead to some disruption in community cohesion, and to changes in the social and sexual norms that influence behaviour.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025