UKR

Feature Story

“With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises”

23 March 2022

23 March 2022 23 March 2022Yana Panfilova is Ukrainian and was born with HIV. When she was 16 years old, she created Teenergizer, a civil society organization to support adolescents and young people living with HIV in Ukraine. Since 2016, Teenergizer has been working internationally, promoting the rights of teenagers and young people in Ukraine and in seven cities in five countries across eastern Europe and central Asia. In 2019, the organization began providing peer counseling and psychological support to adolescents, and has trained more than 120 online consultants–psychologists to support young people across the region. In June 2021, she spoke at the opening of the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on AIDS. When the war in Ukraine started, she left Kyiv, Ukraine, with her family and made her way to Berlin, Germany, from where she is continuing her work to support young people living with HIV in Ukraine.

Why and how did you leave Kyiv?

Within days of the start of the Russian invasion I understood that we needed to make a life-changing decision—people with machine guns were patrolling the streets. I had to convince my mother that we needed to leave, because she was reluctant to go. We packed up our lives in less than an hour, drove to Kyiv railway station, left our car there and boarded the first train that we could find. There were so many people, mothers, children, and fathers and brothers seeing off their families, and many people were panicking. We had to stand on the train for 12 hours, with our suitcases and our cat. When our grandmother caught up with us at our first stop, we travelled together from Ukraine, along with her dog, crossed the border to Poland and went on to Berlin. The entire trip took seven days. It was the longest and most challenging trip of my life—I didn’t want to leave my beautiful Kyiv not knowing where we would end up. Now we are here in Berlin, refugees, safe and secure, but still in disbelief about what we have been through and distraught about what is happening to the people of Ukraine. But at least we are safe and together—my mother, my grandmother and her dog, and me and my cat. I was lucky that I brought enough antiretroviral therapy to last about two months.

Are you settled in Berlin?

I’m still in limbo, like millions of other Ukrainian women and children who have made this journey. But everyone we have met at every step of this journey has been so kind and welcoming. We are now clarifying the legal aspects of how to stay here in Berlin for the next few weeks and how we can access local medical and social services. Even how we can rent an apartment is still not yet clear. We made an appointment online with the municipality of Berlin to clarify the details with them. They are working to provide me with medical insurance so I can get access to medical care and uninterrupted access to HIV treatment.

I am also in contact with Berliner Aids-Hilfe, one of the oldest nongovernmental HIV organizations in Europe; after the war in the former Yugoslavia, they have a lot of experience in working with migrants living with HIV. They have been amazing, ready to help with access to antiretroviral therapy as well as the other needs that Ukrainians living with HIV will have here in Berlin.

So, you're more or less safe now. How are the other young people from Teenergizer doing?

Most of our teenagers living with HIV have already left Ukraine and now they are in Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, Poland and other countries. We are in contact with most of them every day. Some of our activists chose to stay with their parents in Kyiv and other cities that are under attack. We are now clarifying the latest information and trying to monitor where everyone is, and if they are safe. But this is not a quick or easy process. Everyone is now trying just to survive and stay in contact. Our staff, peer educators and clients are now scattered across different countries, each with different laws, treatment regimens and access to the Internet. Those still in Kyiv are connected with our partners, who are still providing access to antiretroviral therapy and emergency humanitarian assistance. Most of our consultants–psychologists are still providing online assistance to those in most in need.

What are the issues you are dealing with to stay in Berlin?

The people here in Berlin and all the Germans we have met since we arrived have been incredibly kind and welcoming. We are very grateful. I know all cities across Europe are struggling to support millions of Ukrainians, but I don’t think we could have found a safer and more tolerant place to stay than Berlin.

Of course, our most urgent questions are of a legal nature related to temporary status here and, second, questions about access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy. Third is housing. I never thought housing would be so important or so nerve-wracking. Local volunteers are helping around the clock, and millions of Europeans have opened up their homes. But for the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians still living in warehouses, shelters and other temporary accommodation, the lack of a place you can call a temporary home can crush your spirit.

What do you think is most important to keep doing now?

No matter what happens with the war, we have to continue supporting each other in the Teenergizer family. In Ukraine, we spent years fighting so that young people living with HIV could have our health and rights protected. And now it feels like so many of our hard-won gains have disappeared overnight. In the middle of this crisis, we have to keep standing up for our rights and focus on the urgent needs facing the most vulnerable members of our Teenergizer network. I am so lucky to be alive and here in the safety of Germany. But many of our friends are still in Kyiv and in other cities across Ukraine, fighting for their lives and our country. Some of them have no way out and others don’t want to leave their homes and their families. Now, more than ever, they need our support and reassurance that we will continue to do everything we can to support them when they need it most.

First, we need to help them to navigate this new crisis and continue life-saving services—HIV treatment for those who urgently need it, and prevention and testing services. Second, during this crisis, we must continue to provide young people with mental health services, especially peer counselling. In our region, HIV is more of a social problem than a health problem. Today, young Ukrainians living with HIV are facing the triple crises of their health, their safety and acute stress and depression caused by the war. Psychologists call it PTSD. This trauma is continuing for an entire generation of Ukrainians. Young people who need professional psychological support will start using drugs and some of them will contract HIV, but they will be too scared or ashamed to ask for help in the current crisis. The same applies to adolescent girls and women who cannot exercise their reproductive and sexual rights, or young people who do not use a condom during sex, or millions of Ukrainian women who are at risk of exploitation when they are alone in Europe, away from their families and friends. Today, thousands of adolescents still in Ukraine who are living with HIV are afraid to reveal their status. Many still do not know how to protect themselves from HIV and from the violence of war. Millions of Ukrainian youth are left alone to cope with their anxieties and fears, and an entire generation will be dealing with post-traumatic disorders—this needs urgent attention. I am convinced that if we provide even basic counselling and support now, young people facing multiple crises will be better able to cope with their problems for years to come.

And also no matter what, we have to push politicians to listen to young people and allow them to influence the decision-making process about their own health and future. The voices of young people, especially young women, should be heard to stop the war and rebuild Ukraine.

How do you see the future of Teenergizer now?

Today, me, my family and my country are facing the greatest crisis of our lives. So if I am not sure about tomorrow, it is difficult to see what the future holds. Over the years, we built a real family, teams of young Teenergizer leaders in different cities in eastern Europe and central Asia—in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, even in Russia. But now we are divided. After the Second World War, Winston Churchill said that there would be a wall. And I think that a new wall is appearing now.

What would you say today if you were again on the podium of the United Nations General Assembly?

This is a war between the old world and the new world.

We are young people who want to live in a new world, where there are no wars, where pandemics such as HIV, tuberculosis and COVID-19 are ended, where poverty and climate change are solved. In this new world, all people, no matter who they are or who they love, whatever language they speak or what passport they hold, can enjoy freedom and live their life with dignity, and travel and move across open borders, between peaceful countries. We learned how important and precious this was in recent years when Ukrainians could travel. We could see how peace-loving people lived in other parts of the world, and it made us appreciate the beauty and freedom we have in Ukraine. Today, more than ever, we only understand what we want to rebuild in our own country when we compare it to the values we find in other countries.

And it is this old world that is financing and sustaining this war. This is a road to nowhere.

With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises.

The new world is about development, not destruction. It is about being able to improve yourself, improve the quality of your life and really support others to do the same.

Everything has an end. And the war will eventually end. What will you do on the first day after the end of the war?

I'll start to read Leo Tolstoy’s book War and peace.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Working together to help refugees in the Republic of Moldova

24 March 2022

24 March 2022 24 March 2022At the start of the invasion of Ukraine, the government of the neighbouring Republic of Moldova estimated that there might be around 300 000 people fleeing to the country from Ukraine. That estimate has now increased to 1 million refugees—a huge amount for a country that has a population of only 2.6 million and is one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Soon after the start of the war, a number of humanitarian organizations, United Nations agencies and civil society partners, coordinated by the government, formed response coordination groups and started to address the most acute needs of the people fleeing the war, including shelter, food, health, social protection, the prevention of gender-based violence and mental health support.

“First, we must focus on the basic needs. A lot is yet to be done around coordination with the many humanitarian organizations joining the response. Because this is also the first time ever for Moldovans to face a crisis of this size, we are learning by doing and learning from experience,” said Iurie Climasevschi, the National AIDS Coordinator at the Hospital of Dermatology and Communicable Diseases in the Republic of Moldova.

Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Country Manager for the Republic of Moldova, visited several displacement centres near the border of Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova. “People are well-received there, the government is ensuring accommodation and food and trying to ensure that children attend school and kindergarten, as about 75% of the refugees are women and children—there are about 40 000 children under 18 years old in the centres,” she said.

According to Ms Plamadeala, almost half of the refugees are being accommodated by families in their homes. “We see the extraordinary mobilization of ordinary people, who are providing remarkable support to people who are fleeing from the war,” she said.

The government’s policy is that Ukrainian refugees will receive the same services as Moldovans, including HIV-related services. “If any of the refugees ask for antiretroviral therapy, we provide it to anyone. We will not refuse anyone if we can help them,” said Mr Climasevschi.

“UNAIDS was part of the planning process right from the very beginning of the crisis to ensure that refugees have access to all HIV-related services that Moldovan people have, including antiretroviral therapy, opioid substitution therapy and HIV and tuberculosis testing,” said Ms Plamadeala. “Stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV is still high. Perhaps not all people living with HIV have been able to access the services, so we are engaging with our civil society partners to proactively provide information to people so they know where to go for support.”

Ruslan Poverga, from the Initiativa Pozitiva nongovernmental organization, said that the organization is already identifying refugees in need of antiretroviral therapy and is referring them to support. “We’ve started proactively informing people, and, if required, providing an integrated package of HIV prevention services, including HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis testing and screening, and the provision of harm reduction and condoms. We will understand the need for such services more clearly in the near future.”

The UNAIDS Country Office for the Republic of Moldova has reallocated funds for urgent humanitarian response needs. This will increase the capacity of the National AIDS Programme to provide antiretroviral therapy to a much larger number of refugees living with HIV. Viral load testing is available to check viral loads if a change of treatment regime is necessary.

“The situation is evolving. We monitor the situation very carefully to understand when and how to look for more support. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is ready to make reallocations if they are needed, and the Republic of Moldova is able to access resources from the Global Fund’s emergency fund. In the event that the National AIDS Programme would be not able to cover the needs, we will look for more support from the Global Fund, UNAIDS, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization,” added Ms Plamadeala.

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

UNAIDS staff member talks about the invasion of Ukraine

18 March 2022

18 March 2022 18 March 2022On 24 February, Olena Sherstyuck, UNAIDS Global Outreach Officer in Ukraine, had no choice but to flee Kyiv. We spoke to her from her new location in western Ukraine.

On 24 February, what were your first thoughts?

Well, my day started very early that day. My son messaged me at 5 a.m. saying, “It looks like the war has begun.” When I went out on my balcony, I heard loud sounds that sounded like bombs.

Is that when you decided to leave Kyiv?

At first, I sat in my car with my cats and then, after checking in with the country director and the rest of the staff, I decided to go to my country house with a garden outside of the city, where I met up with my son and his wife.

Was that safe enough?

When I arrived, I realized this was worse than the city. My house is in fact near the Gostomel Airport, so is a target of missiles. We hardly slept at all. The sky was red and what I love about the place is that there are panoramic windows, but this was not pleasant at all. The windows kept rattling.

So, what did you do next?

On 25 February, at midnight, we decided to leave for western Ukraine. I had worked in the region for five years while working at the United Nations Children’s Fund and had been back since then, so the mountainous region seemed like a good option to me.

It meant driving solidly for 28 hours because we zig-zagged from place to place to avoid fighting and to find alternatives to closed roads or blown-up bridges. We had to change our route constantly. That was quite challenging.

I asked friends in the region to help me find a place to stay, so we are now settled in a wooden house with five rooms and a common kitchen.

Were you liaising with your team and your supervisor?

We are a small UNAIDS office in Ukraine and because of COVID-19 we had all sorts of ways of staying in touch, via WhatsApp, Viber, etc. Every morning we have our regular morning check-ins. That has helped a lot to stay connected. Colleagues from the region and the global hub have also reached out, which keeps me feeling like things are normal.

Normal, really?

I cannot sleep and I cannot eat but the work and meetings and coordinating efforts help keep me grounded—it keeps me going.

I am, however, addicted to the news. It’s impossible to stop watching and reading what is going on. I keep thinking about my apartment in the city and about my garden and when we can all go back to Kyiv.

I have no regrets about leaving. I am not a fighter nor am I in the army, so why get in the way of the people fighting. That first week I was in shock and I thought that it would end quickly, but we are now three weeks in.

I assume you took your passport and phone but what about food and clothing?

I took my key documents and passport and my work computer but only had gardening clothes from my house, so I have been wearing an all-purpose man’s jacket ever since. Let’s just say I am looking a bit disheveled, but I am not the only one! (Laughter.)

As for food, there are small markets and so far we have had no shortages. We are trying to make ourselves busy by joining local women making bread and there are other communal activities organized in the village.

(Interruption) Do you hear that, Charlotte? You heard the sound of the air raid alert? It’s stopped now.

Not having lived through something like this, what advice do you have for us?

First of all, having personal relationships with people really comes in handy in such times. Not only was I able to connect with my current colleagues, I also did so with my former work friends too.

And from the first day, I was able to reach out to the numerous networks of people living with HIV and other nongovernmental organizations I work with to see how they are doing. This meant lots of calls back and forth, but these are professional and personal relationships I have made over the years—I wanted to know if everyone was safe.

I must say we at UNAIDS were really good at sharing and passing on key information regarding what services are available, where and with whom, services such as antiretroviral therapy refills or opioid substitution therapy, and then updating the information. Before the war, I was a member of the national oversight committee and programmatic committee that oversees Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria grants, so my colleagues and I are trying to follow up on programming aspects. It is not easy, and as for monitoring, many people are still hiding in basements, so that complicates things.

Secondly, it is really hard to plan strategically. In the beginning, everyone is making ad hoc decisions. Our partners, other international organizations, basically everyone was scrambling to help and unfortunately there was a lot of duplication. One day I would be asked to find mattresses, another day someone needed gas, now things feel more organized.

I learned that it takes time to understand how to act and react and it’s important to find one’s niche. Don’t try and spread out too much.

Good advice—basically, assign roles and/or tap into each organization’s strengths to work better as a whole?

Exactly. Another thing that has been helpful is to have the global hub’s input. I mainly work with local counterparts—for me, that is 90% of my time and because of all the running around and the forever-changing situation, it has been useful to have HQ give us the bigger picture.

How so?

It’s reassuring to know that countries, such as Poland and the Republic of Moldova, and people have committed to help Ukraine. I now know what our colleagues in the region are doing regarding antiretroviral therapy stocks and using international assistance. In Ukraine, we adopted more European standards, so, for example, our regulations on medicines and intellectual property are close to European standards and have little in common with former Soviet satellite countries. Our legislations contain chapters on key populations and prohibit discrimination and the Ukrainian Government financed basic HIV prevention services for hundreds of thousands of people from key populations. We also really pushed harm reduction services, since HIV in Ukraine affects mostly people who inject drugs, with thousands of people on opioid substitution therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis. The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people have also been an integral component of the country’s human rights strategy. I can hardly imagine such developments in many eastern European countries.

Any last thoughts?

It’s really important to feel like I have human contact, so do reach out. And I must say I have been impressed by people uniting, Ukraine feels more united to me. That is my one optimistic note in all of this—there has been fantastic support among people. Glory to Ukraine!

Region/country

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

Keeping harm reduction available in Ukraine

09 March 2022

09 March 2022 09 March 2022Ten days after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, UNAIDS spoke to Oleksii Kvytkovskyi, the head of the Volna Donbas Resource Center of the All-Ukrainian Association of People with Drug Addiction, a nongovernmental organization working with people who inject drugs in Ukraine.

How are you feeling Oleksii?

I am tired of fear and fleeing. I have decided I will carry on doing what I have been doing for the past 14 years—defending the rights of key communities, notably people who inject drugs and people in need.

This is not your first encounter with war?

Eight years ago, I was there when the Russian Federation attacked the eastern part of Ukraine—as you know, they are now self-proclaimed republics. I have three children and two were born during that conflict, one in 2014 and the other in 2019.

I still work in four cities in the Luhansk oblast (region), which are controlled by the Ukrainian Government, located almost on the front line: Severodonetsk, Lysychansk, Rubizhne and Kreminna.

What are you currently doing in your job?

We at the nongovernmental organization receive and then deliver opioid substitution therapy (OST) and food and water to those who need it. We only have enough OST until the month’s end. That’s about 28 days, and then I don’t know what we will do.

Access to antiretroviral therapy is also problematic in some cities. Basically, we look at who lacks what and if there are risks of interruption.

Have a lot of people left your area?

Very few people can leave because they don’t have enough funds to do so. Until now they have been evacuating women, small children and the elderly as a priority.

Our nongovernmental organization turned to international organizations and we received assistance from the Eurasian Harm Reduction Network, the Eurasian Network of People who Use Drugs and Volna, and that has really helped to provide urgent assistance.

What about you?

I begged my wife to take the children and leave for Lviv. I even found a place for them to live but she said that she wouldn't leave me, and so she stayed.

But I am afraid. I am anxious about my children and my beloved wife.

What keeps you going?

I go to work every day. People ask me if I fear for my life. My answer to this is, “When you solve someone’s problems, you unknowingly forget about fear and war. Then solving the problem of a person from the community becomes the key objective for you, so you set out to help in any way.”

Region/country

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Opinion

We cannot let war in Ukraine derail HIV, TB and Covid-19 treatment in eastern Europe

09 March 2022

09 March 2022 09 March 2022By Michel Kazatchkine — This article appeared first on The Telegraph

It is no surprise that the World Health Organization (WHO) is calling for oxygen and critical medical supplies to safely reach those who need them in Ukraine and moving to establish safe transit for shipments through Poland. But nor is the call new. We`ve been here before.

Russian annexation of Crimea and the conflict in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Eastern Ukraine in 2014 threatened the supply of HIV and tuberculosis medicines. Fragile trans-internal border efforts and financing by the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria allowed the continued supply of the medicines in the separatist territories despite the conflict during the last eight years.

One has to assume that should Russia occupy new Ukraine territories, the challenges to guarantee people living with tuberculosis and HIV access to those drugs will be just as great, high risk, if not already lost.

The separatist authorities in the Donbass and the Russian administration in Crimea also abruptly stopped opioid agonist therapy (OAT) for people who inject drugs, which resulted in much suffering and deaths from overdose and suicide.

NGOs working with affected communities in Donbass were basically closed down. Decades of fighting HIV and tuberculosis have taught us just how critical civil society, community leadership and human rights are to ending those diseases.

The Russian Federation refuses to countenance OAT as a harm reduction measure to reduce the risk of HIV transmission through shared needles.

Ukraine on the other hand, is a notable champion of harm reduction, including OAT and needle exchange programs. This matters greatly in eastern Europe and central Asia which continues to be home to the fastest growing HIV epidemic in the world.

Some 1.6 million people are living with HIV in the region (with Russia accounting for 70 per cent) and around 146,000 are newly infected each year. Drug use accounts for around 50 per cent of new infections but unprotected sex is set to become the main driver in the coming years.

Ukraine, however, has been one on of the most successful countries in the region in terms of guaranteeing access to antiretroviral drugs – 146,500 people in the past year.

These gains were at risk before the war with Covid-19 restrictions seeing a drop in people testing by a quarter in 2020. The coming weeks and months of war will cause this effort to collapse entirely.

Eastern Europe also remains the global epicentre of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis globally. Despite progress in the last ten years, TB prevalence, mortality levels and particularly, incidence of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis remain high in Ukraine which has the second highest number of cases in the region.

Drug resistant tuberculosis represents around 27.9 per cent of new tuberculosis patients and 43.6 per cent of previously treated patients and treatment success of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is around 50 per cent.

If Covid-19 halved case detection in 2020, it is not hard to imagine it being totally wiped out by the ongoing war.

As health systems collapse and treatment and prevention services are interrupted, mortality from HIV, tuberculosis, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis and Covid-19 will readily increase in Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of people are internally displaced and cities such as Lviv are running short of medicines and medical supplies.

Scarily, the fallout of the invasion will also go beyond Ukraine: over a million refugees have already fled for their lives. The impact of this will be felt across border towns and areas in central Europe whose response to tuberculosis, HIV and more recently Covid-19, has been fragile.

Border locations and neighboring countries will have to anticipate and address an avalanche of new health needs. We are at an impasse: international cooperation and solidarity towards the Eastern European region has not been a strong feature of the last two years of the global pandemic response.

The arrival of WHO health supplies and the formation of a safe corridor for refugees are fragments of good news in this unfolding tragedy, but we need so much more.

Health systems and facilities must be protected, be functional, safe and accessible to all who need essential medical services, and health workers must be protected.

Michel Kazatchkine is Course director at the Graduate Institute for International Affairs and Development in Geneva, Switzerland, and the former UN Secretary General and UNAIDS special Envoy on HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe and central Asia. Previous to that he was the Executive Director of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and malaria.

Region/country

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

Quick thinking and planning instrumental for HIV network in Ukraine

08 March 2022

08 March 2022 08 March 2022When shelling awoke Valeriia Rachynska in Kyiv on 24 February, the first day of the conflict, she rolled over and tried to get more sleep. As a native of Luhansk, she had already lived through the 2014 conflict.

“I think my brain analysed the noise and realized I was out of harm’s way,” she said by videoconference from a small village in western Ukraine. “But when I saw my kids crying and frightened, I knew I had to relocate yet again.”

The following night she and her two sons stayed in a bomb shelter and then left their home in the capital city with her brother and his family.

As the Director of Human Rights, Gender and Community Development of 100% Life, the largest network of people living with HIV in Ukraine, she stressed that in order to continue helping people, she needed to relocate to a safer place.

“It’s like when you are in an airplane and there is a lack of oxygen,” Ms Rachynska explained. “You put the mask on yourself first then place it on others afterwards.”

The key for her and her organization was being able to have Internet access, a steady mobile phone service, open banks and a relative sense of safety. These days she felt like she was operating a switchboard.

“I respond to all calls and try to redirect them to the right people,” she said. “It has been non-stop and because there are so many attacks and so much unpredictability, I can only advance one step at a time.”

She credits 100% Life’s head, Dmytro Sherembey, for having done advance planning ahead.

“A lot of people told us, “You are crazy to panic,” but at 100% Life we moved our computer servers, documents and anything deemed sensitive to western Ukraine and even Poland and Germany.”

Some of her colleagues stayed in Kyiv saying they would tough it out, but 10 days later many of them left too.

“We are now focusing on evacuations and relocation for people living with HIV and their families as well as marginalized groups by hiring buses for them,” Ms Rachynska said, wrapped up in a blue sweatshirt with a hood. “For those not living in Kyiv, we are sending money via bank transfers for them to buy food and other essentials.”

The country has enough buffer stocks of HIV medications to last until April, but with the help of international partners and UNAIDS’ coordination, 100% Life has urgently planned to have additional life-saving medicines delivered to Poland. The Polish Government has secured a warehouse and agreed to help with logistics, getting antiretroviral therapy to people living with HIV in Ukraine.

Ukraine has the second largest AIDS epidemic in the region. It’s estimated that 250 000 people live with HIV in Ukraine, with more than half on antiretroviral therapy, medication that needs to be taken daily for people living with HIV to stay healthy.

“Our biggest challenge right now is to save lives, provide security and have people stay on treatment,” she said. The 100% Life network has already redesigned key aspects of its programme to get funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to meet the immediate needs.

Having joined 100% Life in 2011, Ms Rachynska has seen the strides that Ukraine has made to reverse the AIDS epidemic. She is particularly proud of the positive impact that harm reduction programmes, including opioid substitution therapy and needle–syringe exchanges, have had in Ukraine to reduce new HIV infections. HIV in the country continues to disproportionately affect people who inject drugs and the ongoing military offensive may hamper substitution therapy options. She said that 100% Life was actively working to avoid that.

Her other worry involved protecting sex workers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people and people who inject drugs. Based on the violence and stigma those groups experienced during the conflict in eastern Ukraine, she fears that key populations will be the targets of violence.

“Our next task will be to start and monitor human rights violations,” she said. “This is very important to me.”

Region/country

Related

Press Statement

UNAIDS urges protection and continuity of health and HIV services for people living with and affected by HIV in Ukraine

25 February 2022 25 February 2022GENEVA, 25 February 2022—Amidst the ongoing military offensive against Ukraine, UNAIDS is calling for the protection of health workers and uninterrupted continuation of HIV and health services for all people, including people living with and affected by HIV. Ukraine has the second largest AIDS epidemic in the region. It is estimated that there are 260 000 people living with HIV in Ukraine, 152 000 of whom are on antiretroviral therapy, medication that needs to be taken daily for people to remain alive and well.

“People living with HIV in Ukraine only have a few weeks of antiretroviral therapy remaining with them, and without continuous access their lives are at risk,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director. “The hundreds of thousands of people living with and affected by HIV in Ukraine must have unbroken access to life-saving HIV services, including HIV prevention, testing and treatment.”

To date, the Government of Ukraine, together with civil society and international organizations, has implemented one of the largest and most effective HIV responses in eastern Europe and central Asia. However, with the ongoing military offensive, the efforts and gains made in responding to HIV are in serious risk of being reversed, putting even more lives in danger.

The right to health and access to HIV services must always be protected, and health workers, representatives of civil society and their clients must never be targets in a conflict. The ongoing military conflict has affected everyone in Ukraine but is likely to be particularly hard for people living with HIV and key populations, including people who use drugs, sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men and transgender people.

As highlighted by the United Nations Secretary-General, the United Nations is committed to support people in Ukraine, who have already suffered from “so much death, destruction and displacement” from the military offensive, in their time of need.

With the support of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and UNAIDS, the Government of Ukraine and civil society partners have delivered HIV prevention and treatment services for people living with HIV and key populations across Ukraine for many years and stand ready to give further support during the ongoing crisis.

UNAIDS staff remain on the ground in Ukraine, working to ensure that people living with HIV and key populations in Ukraine have continued access to life-saving services, with a particular focus on the most vulnerable civilians. UNAIDS will continue to support HIV prevention, testing, treatment, care and support for people across Ukraine affected by the crisis.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Region/country

Feature Story

100% Life: 20 years of fighting

04 May 2021

04 May 2021 04 May 2021100% Life, formerly known as the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV, the largest organization for people living with HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia, is marking its 20th anniversary on 5 May. Those 20 years have seen it work on the most challenging issues of the HIV response in Ukraine, on health-care reform and overcoming stigma and discrimination and barriers to accessing health services.

The organization works to provide 100% access to treatment to 100% of Ukrainian people living with HIV. It strives to improve the quality of life for people living with HIV and promotes the rights and freedoms of people living with HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis C, including the right to self-determination and the right to make decisions that directly influence their lives.

Beginning with seven members in 2001, today it has grown to 474 members and 15 000 associate members. The first office was opened in Kyiv and now the organization unites 24 regional offices across the country.

In 2004, the organization, together with partners, prevented interruptions of antiretroviral therapy for 137 patients. At the end of 2019, 100% Life was purchasing HIV medicine for 113 000 people.

“Over the years of work, we have purchased 7 230 000 packs of antiretroviral therapy,” said Dmitry Sherembey, head of the 100% Life Coordinating Council. Think about these figures! Behind each of them is a saved life. We are grateful to all our partners who believed in us and continue to believe.”

In 2016, the first 100% Life medical centre was opened in Kyiv. Five years later, three more centres have been opened in Ukraine, in Poltava, Rivne and Chernihiv. These centres are the first clinics created by patients for patients, where services are provided free from stigma and discrimination.

“I have great respect for the struggle that the organization has waged against stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and other vulnerable people. It is thanks to 100% Life that the first opioid substitution therapy programmes for people who use drugs in Ukraine started, sex workers began to speak openly about their rights and people living with HIV had hope for a normal life, medical care and help from the state,” said Raman Hailevich, the UNAIDS Country Director for Ukraine.

In 2016, the organization received the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) award for the best partnership among the 40 countries in which PEPFAR operates.

The same year, there was a breakthrough in state funding of the HIV response, which was increased by 2.3 times. The success of the 20/50/80 transition plan is partly because of the efforts of 100% Life, which worked with the government and advocated for increases in the HIV budget, access to treatment and the optimization of health-care systems.

The struggle of 100% Life won’t stop. New problems come along that need to be addressed.

“We are now facing a new challenge—the COVID-19 pandemic,” added Mr Sherembey. “Our experience gained over the years of interaction with government agencies, partners and donors allows us to contribute to the common cause of the struggle. With the support of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and USAID, almost a million pieces of personal protective equipment have been purchased for Ukrainian doctors and social workers, 200 000 tests for COVID-19 have been bought, equipment for oxygen stations at hospitals has been procured, information campaigns on vaccination against COVID-19 have been conducted, and much more is being done.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

Turning around the HIV response in Odesa

24 November 2020

24 November 2020 24 November 2020Irina Kutsenko, a deputy of the Odesa City Council in Ukraine responsible for social issues, is an active advocate of community rights who campaigned for medical and social services for HIV to be brought closer to the most disadvantaged. She is the first and so far the only government official nominated by civil society for the #inYourPower award. The award, which is given by civil society to leaders, government officials and eastern European and central Asian politicians, is given to people who have contributed to improving the financial sustainability and effectiveness of HIV programmes for key populations and to removing legal barriers to HIV services and protecting human rights.

However, the route to the award was not straightforward. “As a deputy, I closed the opioid substitution therapy site in my district. I collected signatures from people against the gay movement in our city,” she said. But after completing a course run by the International Academy of Harm Reduction, she began to research the topic in more detail. “I started reading about the issue on the Internet, listening to interviews of people, listening to life stories, until I understood that I was wrong!”

Ms Kutsenko started to cooperate with community organizations to make Odesa a safer city for key populations.

“When representatives of community organizations came to me with a harm reduction project in the city, I already understood what they were talking about. At that moment, I realized that nongovernmental organizations today know more than officials. At the beginning, I was only listening,” she said.

The first task for Ms Kutsenko and the community organizations was to find a common language and common platform. “We needed everyone: doctors, the authorities and public organizations to unite and work towards one common goal,” she said. “It didn't work out when everyone was separate.”

But, as Gennadiy Trukhanov, the Mayor of Odesa, said, it was not easy for the city. The city authorities, in addition to responding to local everyday problems also need to address global challenges, in particular helping health-care workers to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. “Mayors are assessed by the state of the city: roads, public spaces, etc. We can have clean cities, but with the spread of infectious diseases around the world, the time may come when there will be no one to walk along these roads,” he said.

Over the past few years, Odesa has been implementing steps within the framework of the Paris Declaration to end the AIDS epidemic in cities and was the first city in Ukraine to commit to the Zero TB Cities initiative. The city has initiated outpatient treatment of tuberculosis, instead of in hospital, and has begun widescale testing programmes for HIV, increasing the detection rate of HIV and ensuring that people who test positive access treatment.

“Of course, there are still many problems, but, step by step, we are changing the situation in the city,” said Ms Kutsenko.

Ms Kutsenko’s story can be viewed on YouTube.

Feature Story

20–50–80 to reach 100 in Ukraine

06 November 2020

06 November 2020 06 November 2020Ukraine has announced that it is now funding 80% of its national HIV response’s HIV prevention, care and support programmes.

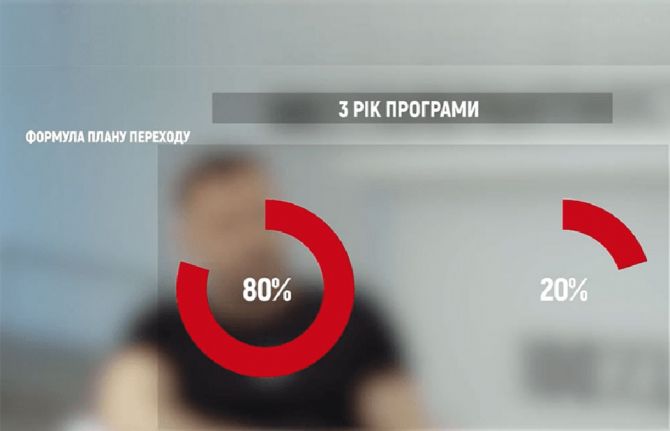

Under its 20–50–80 transition plan, which began in 2018, the government committed to increasing its share of the funding of HIV prevention, care and support programmes, which previously were fully funded by international donors, over three years. In the first year of the transition plan, the state was to finance 20% of those programmes, with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) providing 80%. In the second year, the ratio was to reach 50/50 and in the third year 80% of funding was to be provided by the state, with 20% from by the Global Fund. This level of funding, which comes from both national and local budgets and is for prevention, care and support programmes within the national HIV and tuberculosis (TB) response and for the procurement of HIV/TB-related services from community organizations, has now been achieved.

The transition plan was proposed by a group of public and community organizations led by 100% Life, formerly called the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV. Dmytro Sherembey, the Head of the Board of 100% Life, said that most of the funding of the country’s HIV response used to come from donors, primarily the Global Fund. The 20–50–80 formula provided a simple algorithm tied to an agreed timeframe and obliged the government to increase domestic funding, since under the plan donor financing would be stopped if the government failed to meet its obligations.

“It was not an easy decision. It would have been easier to just sign a grant with the Global Fund. But we understood that if the government did not increase its funding, about half a million people who use the services would be left with nothing,” said Mr Sherembey. Also, since the government is unable to provide a wide spectrum of HIV prevention, care and support services on its own, community organizations have stepped in. However, there was a worry that reduced funding for community organizations would result in their being unable to provide such services, resulting in hundreds of thousands of people being deprived of care.

A Strategic Group for the Implementation of the Transition Plan, which included the Public Health Centre of Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, 100% Life, UNAIDS, the ICF Alliance for Public Health, Renaissance and Deloitte, developed new mechanisms through which local community organizations could cooperate with local authorities. The Sumy and Poltava regions of Ukraine were the first to start financing HIV and TB programmes from domestic funding. In 2018, the equivalent of more than US$ 650 000 was allocated to the programmes from Ukraine’s state budget.

“The transition plan provides an opportunity to continuously strengthen links between government and nongovernmental organizations in the provision of quality services to people living with HIV and tuberculosis. Nongovernmental organizations are moving away from their former role of volunteer activists and are starting to carry out professional social work and are accountable for its results. And the state, in turn, purchases their services through the public procurement system,” said Igor Kuzin, the Acting Director of the Centre for Public Health of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine.

With the support of Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance, the implementation of the transition plan progressed. In 2019, about US$ 4 million was allocated, equal to 50% of funding, which reached 25 regions in Ukraine. In 2020, the cost to the government of treatment and other services is expected to be about US$ 12.5 million, which is 80% of funding for such programmes.

“Together with the Public Health Centre of Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, and international and civil society partners, we will carefully monitor and analyse the results of this new model of HIV service delivery in order to ensure its sustainability, effectiveness and consistency,” said Raman Hailevich, the UNAIDS Country Director for Ukraine.