Feature Story

Viet Nam gets more value for money through integration of HIV services

24 October 2014

24 October 2014 24 October 2014A “one-stop-shop” health centre in Hanoi is providing integrated HIV and other healthcare services that are achieving progress and maximizing investments in the AIDS response in Viet Nam. Hanoi’s South Tu Liem district health centre is a model that the Viet Nam Authority for HIV/AIDS Control plans to replicate in high-burden areas of the country.

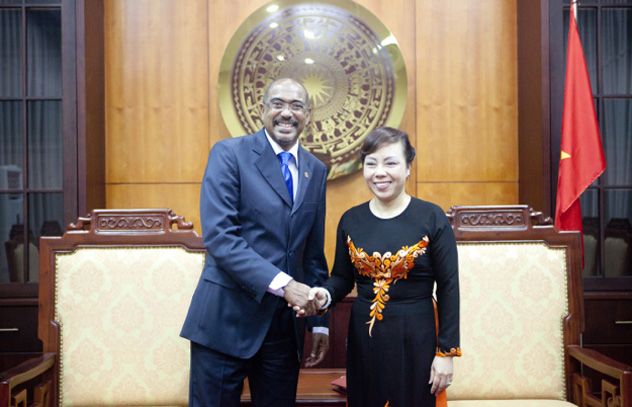

“Today I saw three things which will help not only Viet Nam but also other countries; integration and decentralization of services; a patient-centred approach; and peer support,” said UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé during a tour of the health centre. “It is important to bring people together from different social backgrounds and support them to become actors for change for HIV.”

The health centre provides a full range of HIV services to key populations, including people who inject drugs, sex workers and men who have sex with men. It is also the primary healthcare centre for the district’s general population. More than 500 people are receiving antiretroviral treatment and more than 300 people who inject drugs are on methadone maintenance therapy. The health centre also has peer outreach services, including needle and syringe distribution, HIV counselling and testing, tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, as well as home-based care and peer support for treatment adherence.

Integration and decentralization of HIV service delivery systems, including health systems strengthening, is one of the strategic priorities put forward by Viet Nam’s new Investment Case for an optimized HIV response. The Investment Case, developed by the Minister of Health with support from UNAIDS and other development partners, aims to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of the national response as international donors reduce their support to rapidly developing Viet Nam.

During a meeting with Mr Sidibé the Minister of Health Nguyen Thi Kim Tien said that Viet Nam is committed to following the Investment Case and increasing the domestic budget for the HIV response. However, she said Viet Nam needed the continued support of the international community to achieve global HIV targets. “We are faced with some challenges and difficulties, but we will try our best and work to sustain the HIV response and make greater achievements,” said Nguyen Thi Kim Tien.

The Investment Case finds that integration and decentralization will save money and help sustain HIV services by avoiding parallel spending on infrastructure, human resources and commodities; taking advantage of the health system’s existing cost efficiencies; creating links between related services; and facilitating referrals.

This approach will also help address some of the concerns that civil society have in Viet Nam. People living with HIV and key populations at higher risk of HIV infection worry that less donor funding could mean reduced access to affordable services.

“I’ve been on antiretroviral treatment for 10 years and I feel very good, like many other people,” said Nguyen Xuan Quynh, 41. “I heard that international support will end soon and maybe we must pay. But most of us are very poor.”

As part of his two-day official visit to the country, Mr Sidibé also met with leaders of civil society networks. He urged them to continue raising their voice on the issues that matter most, and to work closely with the public healthcare system to play a greater role in the provision of lower-cost and higher-impact HIV services.