Feature Story

Desperately seeking an HIV cure: Belgian research centre studies viral rebound

17 October 2019

17 October 2019 17 October 2019Growing up, Linos Vandekerckhove loved biology, so it seemed an obvious choice to go to medical school. After two years of practising internal medicine, in 2001 he had a chance to spend a year in South Africa.

“Here I was, in the eye of the storm, where most days one person would come to the clinic and die within 48 hours from an AIDS-related illness,” he said.

He returned to his native Belgium shaken. “It was really shocking to me, because in Europe treatment was readily available, so suddenly I felt like some people pay a very high price.”

IS THERE A CURE FOR HIV? There is no cure for HIV. However, there is effective treatment, which, if started promptly and taken regularly, results in a quality and length of life for someone living with HIV that is similar to that expected in the absence of infection.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT HIV AND AIDS

Not wanting to plunge back into a hospital setting, he opted to work for a few days a week in an HIV virology laboratory. After getting his PhD, he wanted to continue researching HIV, so he joined the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. After a few years of working with patients, he finally had more time to spend on research. In 2009, he started his own laboratory, the HIV Cure Research Center Ghent, and a year later he spent five months in San Francisco, United States of America, to familiarize himself with research on a cure.

“The sabbatical helped me gain momentum,” he explained. His research laboratory now employs 20 people.

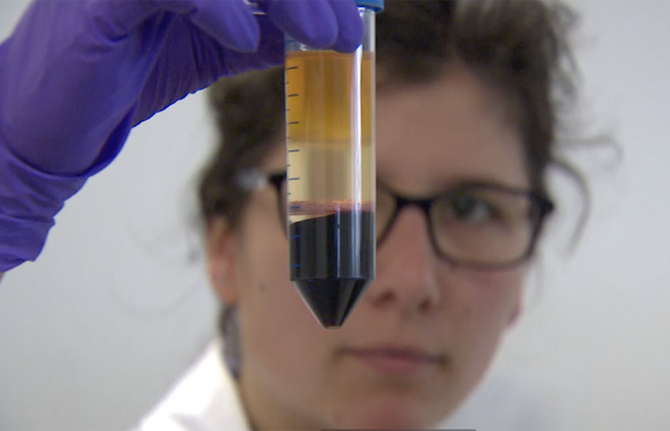

Recently, his team completed a study with 11 people living with HIV. It involved pausing antiretroviral therapy so that scientists could observe viral rebound.

“An ethics committee had to validate the study and, of course, we held a patient forum to analyse the stress factors associated with taking people off treatment and the subsequent tests on them,” Mr Vandekerckhove said. His team made sure that the eight to nine procedures would be minimally invasive and carried out in a day, so that the volunteers could return to work after two days. To minimize any further disruption, technical assistants went to each person’s home to regularly gather blood samples.

“We wanted to involve the volunteers as much as possible and show our support from A to Z,” he said.

Two patterns surfaced from the study. Viral rebound, which took 15–36 days, occurs randomly. The team found more than 200 independent rebound events, from the gut to the lymph nodes to “just about everywhere where immune cells are present.”

Mr Vandekerckhove’s team also found that, depending on where the virus rebounded in a part of the body, the virus had evolved with its own individual make-up, like a barcode or a fingerprint. The researchers found different viruses, showing that they are not all the same single virus that has emerged from a reservoir, but rather multiple re-emergent events.

“We analysed 30 barcodes per cell type and about 400 barcodes per person,” he said.

That’s when they asked for help from virologists and statisticians.

“Our study revealed that having a medicine that would only target the lymph nodes is wrong. What this shows is that you need to focus on many organs, not just one,” Mr Vandekerckhove said.

UNAIDS Science Adviser Peter Godfrey-Faussett congratulated the HIV Cure Research Center Ghent. “Such detailed work advances our understanding of reservoirs where HIV “hides” while treatment suppresses the virus in the blood,” he said.

In his opinion, the research highlights the many challenges of the virus, since HIV can rebound from a wide range of reservoirs. “This is why a clear understanding of the nature of the reservoirs is so important to find a cure.”

Mr Vandekerckhove remains very positive, pointing to how gene therapy used to be science fiction but is now a reality.

“We need to bring the world of research to the world of patients,” he said. In his mind, a cure is one of the many facets of HIV that we cannot overlook.

Fellow Belgian Jonathan Bossaer couldn’t agree more. Ten years ago, he became very ill in South Africa and soon found out he had contracted HIV. After many years of feeling lost, a friend’s death made him realize he had to change.

“I was able to free myself of the frustration and shame that I had been living with for almost eight years and let go,” Mr Bossaer said. He founded a charity to raise awareness about HIV stigma. “Positively Alive has three main objectives: educate people about HIV, normalize HIV and help end HIV by raising funds,” he explained.

Half the funds go to a South African orphanage and the other half to Mr Vandekerckhove’s research centre. “Ending the HIV and AIDS epidemic is an enormous challenge and research for a cure and a vaccine needs our full support,” he said.

Pausing a bit, Mr Bossaer said, “The fight is far from over, but we are on the right path.”