Feature Story

Statement by the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board Bureau

25 September 2025

25 September 2025 25 September 2025GENEVA, 25 September 2025— Following the publication of the UN80 Initiative progress report on 18 September 2025, the Bureau of the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB Bureau) convened an extraordinary meeting on 22 September to discuss the report’s proposal related to UNAIDS.

The PCB Bureau—comprising Brazil (Chair), the Netherlands (Vice-Chair), Kenya (Rapporteur), the NGO Delegation, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) as Chair of the Committee of Cosponsoring Organizations (CCO)—reaffirmed the decisions taken by the UNAIDS Board and the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in June and July 2025, which provide a clear, two-phase roadmap for the transformation of UNAIDS. As these are consensus decisions by the governing bodies of the UNAIDS Joint Programme, the Bureau believes they are critical elements of any next steps in UN80 deliberations as they pertain to UNAIDS.

The decisions of the UNAIDS Board in June 2025 have been based on an inclusive process involving all stakeholders in the AIDS response and initiated by the UNAIDS Board in December 2023 at its 53rd meeting, where the Board requested the UNAIDS Executive Director and the CCO to revisit the operating model.

To that end, the UNAIDS Executive Director and the ILO Director General, on behalf of the Joint Programme, convened a High-Level Panel of diverse stakeholders in the HIV response, which made a set of recommendations to the Joint Programme.

On the basis of these recommendations, the UNAIDS Executive Director and the Director-General of the ILO presented a revised operating model to the Board for its consideration and the Board made the following decisions:

- Welcomes the work and recommendations of the High-Level Panel on a resilient and fit-for-purpose UNAIDS Joint Programme in the context of the sustainability of the HIV response;

- Takes note of the Executive Director and CCO’s Report on the recommendations for revisions to the Joint Programme operating model (UNAIDS/PCB(56)25.15);

- Welcomes the clear articulation of the Secretariat’s four core functions as (1) leadership and advocacy; (2) convening and coordination; (3) accountability through data, targets, strategy; and (4) community engagement, while requesting that actions to address inequalities are integrated across these four priorities and recalling the guiding principles of UNAIDS’ work;

- Endorses the revised operating model of the Joint Programme, as set out in this report (UNAIDS/PCB(56)25.15), noting that additional decisions will be taken on the operating model at the Special Session of the PCB in October 2025 and subsequent PCB meetings in line with future decisions of the UN80 Initiative.

- Requests the Executive Director to provide regular updates on the operationalization of the revised operating model starting at the 57th PCB meeting in December 2025;

- Requests the Executive Director, to define a review process of the revised operating model by the 57th PCB in December 2025, in consultation with the Cosponsors and PCB stakeholders, and undertake that review by June 2027 at the latest to inform the PCB’s decision making, subject to ECOSOC decisions, on the further transition of the Joint Programme within the wider UN system to sustain global progress towards ending AIDS as a public health threat.

In July, these decisions were formally noted by ECOSOC in consensus Resolution E/RES/2025/20 on the Joint Programme (https://docs.un.org/en/E/RES/2025/20).

During its discussions on 22 September, Bureau members highlighted the importance of protecting the integrity of the reform process underway and avoiding further disruption to the HIV response, expressing concern that the UN80 progress report did not reflect the recent Board and ECOSOC decisions, leading to confusion among stakeholders, particularly civil society and donors.

The Bureau recalled that the proposals in the UN80 report are non-binding and that it is the responsibility of the governing bodies to determine the way forward, as emphasized by the Secretary-General. In this context, the Bureau has added an agenda item on implementation of the UNAIDS revised operating model and UN80 to the Special Session of the PCB on 8 October 2025, before the UNAIDS Board considers the 2026 Workplan and Budget.

The PCB Bureau acknowledges UNAIDS' commitment to a transparent, inclusive and responsible transformation, adhering to the decisions of its governing bodies, aligned with the broader objectives of UN80 reform and towards achieving the goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Feature Story

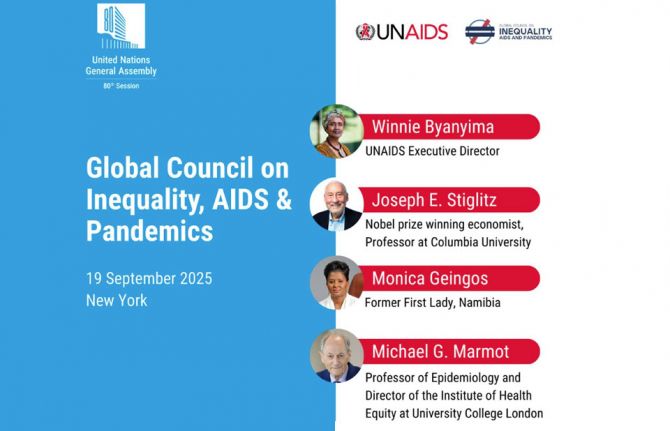

Ahead of UNGA, global experts investigate how inequalities are making the world more vulnerable to pandemics

22 September 2025

22 September 2025 22 September 2025In advance of the UN General Assembly High-Level Meetings, a group of experts co-chaired by Nobel prize winning economist Joe Stiglitz, former First Lady of Namibia Monica Geingos, and Director of the Institute of Health Equity Sir Michael Marmot met to review how inequality gaps within and between countries are impacting global health security. Economists, public health experts, and current and former government leaders from around the world took part in the meeting of the Global Council on Inequality, AIDS and Pandemics.

The Council convened in New York at a time of growing concern that governance, economic, and social crises are undermining the world’s capacity to respond to current and future disease outbreaks. Council members will meet with world leaders gathered this week at the UNGA.

A synthesis of the findings gathered over two years by the Council will be published in November ahead of the G20. It will cover issues including the debt crisis, social determinants, access to pandemic products, and the struggling role of community organizations in the current global environment.

“Deepening inequalities are dangerous,” said UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima, who convened the Council. “When we set up this Council two years ago, it was with a clear vision: to collect the evidence, advocate for the policies, and secure the action needed to address the inequalities that make disease outbreaks more frequent, that accelerate the spread of disease and that intensify and prolong the impacts of pandemics.”

“When global rules leave some countries unable to protect their populations from current or future pandemics, that does not only endanger people in those countries, it endangers people in all countries,” said Joe Stiglitz.

“The need to tackle inequalities worldwide is not only a moral responsibility. It is essential for ensuring a safe and secure world. Tackling inequality, protecting everyone’s rights, is in everyone’s interests,” said Monica Geingos.

“None of the inequalities that threaten public health are immutable. They can all be tackled through proven policies and investments. Inequalities can be overcome if leaders follow the evidence,” said Michael Marmot.

Find out more about the work of the Global Council on Inequality, AIDS, and Pandemics at https://www.inequalitycouncil.org

Feature Story

UNAIDS at the 80th United Nations General Assembly

17 September 2025

17 September 2025 17 September 2025At the 80th session of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) global leaders will convene to build consensus and confront complex global challenges. The 80th Session will be presided by Ms Annalena Baerbock of Germany. Her vision: “Better Together - Joining efforts to forge a better future for all."

UNAIDS, as the steward of the global HIV response and a long-standing advocate for people-centered and inclusive approaches, will reaffirm how the voices of communities remain central to the dialogues at the UNGA. High-Level Week offers a critical platform to advocate for integrated, multisectoral approaches that advance health, rights, and resilience.

THREE KEY MESSAGES UNAIDS WILL BRING TO #UNGA80

REVERSE THE FUNDING CUTS AND EXPAND ACCES TO HIV MEDICINES

Massive cuts to HIV funding are putting lives in jeopardy. The 40 million people living with HIV need antiretroviral treatment yet cuts to funding are reducing access – putting millions of lives in danger. This must be reversed particularly as breakthrough new medicines are coming to market that can prevent transmission of HIV with injections just twice a year. Research shows the medicine – lenacapavir - can be made for just US$ 25 per person per year, but the current cost is US$ 28,000 – unaffordable and out of reach for the people who need it most including young women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa. We will be advocating for access to medicines for all!

RELATED EVENTS:

Friday 19 September 2025 - 09:00 – 17:30 (ET)

Global Council on Inequality, AIDS and Pandemics, convened by UNAIDS

This session will provide an overview of research showing that inequality is driving pandemics; pandemics increase inequality; and that we are more vulnerable because of it.

Tuesday 23 September 09:00 – 11:00 (ET)

G20 Social Summit Side Event "Advancing Inclusive Growth, Social Justice and Human - Centered Development" hosted by South Africa in partnership with UNDP and Open Society Foundation

This event will explore how the G20 can lead inclusive and just responses to global crises, aligned with South Africa’s G20 priorities on climate resilience, debt sustainability, a just energy transition, and the governance of critical minerals. It will also highlight the role of the G20 Social Summit as a platform for inclusive engagement with youth, civil society, women, labour, and grassroots movements.

Tuesday 23 September 16:00 – 17:00 (ET)

From Accra to the World - Launching the High-Level Panel on Reimagining Global Health Governance

H.E. President John Dramani Mahama, President of the Republic of Ghana, will host a Presidential Side Event to formally announce and launch a bold new High-Level Panel on Reimagining the Global Health Governance.

Wednesday 24 September 07:00 – 09:15 (ET)

Annual Prayer Breakfast: Protecting Every Child, Upholding Every Life

Wednesday 24 September 2025 - 09:00 – 11:00 AM (ET)

Equity and integration: Reshaping health systems through people-centred primary care – a call for convergence and co-investment

Leaders will gather to discuss how integrated, people-centred primary health care can build stronger health systems, improve access to diagnostics & treatment, bridge NCDs, mental health & infectious diseases and advance universal health coverage.

Registration link here.

Wednesday 24 September 20:00 – 22:00 (ET)

The Global Fund’s Eighth Replenishment Reception: Honoring Bold Leadership, Committing to Impact

This event will convene leaders to reaffirm a shared commitment to saving lives, strengthening health systems and advancing equity. As the Global Fund’s Eight Replenishment approaches, it is a moment to celebrate achievements, spotlight new commitments and honour the leadership of donors and partners.

Thursday 25 September 08:00 – 09:30 (ET)

Access to Medicines: The Fight for Health Justice in an Age of Retreat

Event organized by Public Citizen, UNAIDS and People’s Medicines Alliance (PMA) access to medicines and moving forward together.

Thursday 25 September 11:00-12:00

Nizami Ganjavi International Center (NGIC) High-Level Meeting – Panel 6 Global Health and Pandemic Preparedness

Keynote speech by the Executive Director of UNAIDS.

FIGHT THE BACKLASH AGAINST GENDER INEQUALITY

Thirty years ago, thousands of women came together in Beijing demanding action for gender equality. Yet today, we are seeing a well-funded, globally-coordinated backlash against gender equality and the human rights of women and girls. Women’s rights are human rights - we need to fight the targeted restrictions on the rights of women and girls, LGBTQI+ people and ensure sexual and reproductive health and rights for everyone.

RELATED EVENTS:

Monday 22 September 10:00 – 20:00 (ET)

High-level Meeting on the 30th Anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women

Click here for more information.

Monday 22 September 12:00-13:30 (ET)

Women Rise for All Lunch convened by the United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed

Building on the success of past Women Rise for All Lunches, the event will continue to celebrate transformative leadership in advancing the SDG’s. This event will connect influential leaders globally, providing a platform to share insights, strategies, and strengthen networks aimed at driving sustainable development.

Tuesday 23 September 09:30 – 12:00 (ET)

Building Resilience for Women and Girls in the Face of Climate Change and Conflict

This gathering, organized by the Organization of African First Ladies for Development will bring together First Ladies, policymakers, global advocates, youth leaders, and partners to drive collective action to protect and empower women and girls in climate-affected and conflict-prone settings.

UN80 – AN OPPORTUNITY TO REDEFINE GLOBAL COOPERATION

The world is in crisis. But the UN was born in crisis, and the UN Charter sets out a roadmap to a better world. Today, we should take the next leap forward. UNAIDS is already undergoing a two-phase transformation in line with the ambition of UN80. UN80 is our opportunity to rise and redefine global cooperation. Our time to rebuild a multilateral system that is more just, inclusive and truly fit for the complex, intersecting crises of our time.

RELATED EVENTS:

Monday 22 September 09:00 – 10:00 (ET)

High-level Meeting to Commemorate the 80th Anniversary of the United Nations

Click here for more information.

Monday 22 September 14:00 – 16:00 (ET)

SDG Moment

The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025 reminds us that the SDGs have already transformed millions of lives. But to fully realize their promise, we need to pick up the pace. To reflect on successes that can inform action in the next five years, the UNSG will convene the SDG Moment during #UNGA80 which will be streamed live on UN webtv.

Thursday 25 September 12:30 – 14:00 (ET)

Rescuing health-related SDGs in times of crisis: aligning multilateral collaboration for country impact, co-sponsored by the governments of Thailand, Angola and Spain

Progress on health-related SDGs is badly off track and the global health ecosystem must evolve and adapt to be fit-for-purpose. This event will convene leaders to find innovative approaches to sustainable health financing, and concrete ways to make multilateralism more efficient and coherent.

ADDITIONAL KEY EVENTS

Monday 22 September

Prince Harry, Charlize Theron, Magic Johnson, and Thuso Mbedu deliver a compelling call to action in new UNAIDS film to be screened at the United Nations

UNAIDS is partnering with acclaimed Hollywood writer and producer Ron Nyswaner to highlight the impact of the global AIDS funding crisis in a new short film to be screened at the United Nations’ global gathering on September 22nd. The short film features longstanding advocates in the global fight against HIV, including Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex, Charlize Theron, Earvin “Magic” Johnson and actress Thuso Mbedu. Together they highlight the need for global solidarity and sustained support to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Feature Story

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

12 September 2025 12 September 2025Lidiia comes from the Zaporizhzhia region, just steps away from Ukraine’s front line. After the full-scale invasion in 2022, her village fell under occupation. She lived in uncertainty for several long months.

“Staying there was unbearable — especially for women. It was constant fear — a nightmare,” she said. “The humanitarian situation was dire: aid vehicles couldn’t reach us, and some were simply shot at.”

Cut off from humanitarian assistance, Lidiia struggled to find basic supplies — food and hygiene products for herself and her young daughter. Most critical for her was not knowing where she could get her supply of antiretroviral therapy for HIV. People living with HIV take a daily pill to keep the virus at bay.

When medicine shortages reached a critical point, she fled her village. Before the war, the road to the eastern city of Dnipro took just three hours; this time, it took three days. Lidiia carried her baby daughter in her arms while pregnant with her son. Exhausted, she had no clear destination.

After days of uncertainty they reached Dnipro, where they found shelter run by the community-based organization “100% Life. Dnipro”. This safe haven welcomes primarily displaced people living with HIV or at high risk of infection, with a special focus on women and mothers with children. The shelters opened as part of the UNAIDS Emergency Fund 2022-2024 thanks to donor support. This shelter is among three in the Dnipropetrovsk region. They offer housing, food, hygiene products, and access to antenatal, pediatric, and HIV care. For mothers like Lidiia, it is not just shelter — it is a lifeline.

“I’m grateful we’re safe,” she said three years after arriving there. “But I still dream of going home — of walking through our front door again and knowing the war is over.”

According to UNHCR, 3.7 million people remain internally displaced within Ukraine, while another 6.9 million have sought refuge abroad. A large proportion are women and children, including many living with HIV and other vulnerable groups. Community-led research by community organisation, “Positive Women”, supported by UNAIDS and UN Women, surveyed 320 women living with HIV across Ukraine in late 2023–early 2024. It confirmed that women living with HIV are facing a triple burden: displacement, gender-based violence, and barriers in access to essential health services.

More than 70% of respondents reported worsening household economic well-being, and over a third lost property. One in six lost their jobs or businesses. Many women described being unable to meet even the most basic needs for themselves and their children. Barriers to health care have also increased as the war drags on. A third of women reported greater difficulties in reaching HIV services due to destroyed infrastructure, insecurity, or lack of resources. Women also reported high levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, compounded by caregiving responsibilities and separation from family.

Despite this, most managed to continue their life-saving medicine thanks to emergency distribution and community support.

For many this is a testament to the resilience of Ukraine’s health system and its civil society.

“The resilience of women like Lidiia, together with the findings of community-led research, highlight both the urgency and the possibility of action,” said Gabriela Ionascu, UNAIDS Country Director for Ukraine.“With sustained international support, community engagement, and rights-based approaches, access to vital services can be preserved—even in the most challenging of times.”

Region/country

Feature Story

Lower prices needed for new HIV prevention medicine in Brazil

09 September 2025

09 September 2025 09 September 2025Civil society representatives are demanding an urgent price reduction for long-acting injectable HIV medicines which prevent HIV.

During a public hearing at the Chamber of Deputies in Brazil, representatives called for strategies to expand access to innovative injectable HIV medications, including lenacapavir and cabotegravir, which have demonstrated more than 95% efficacy in preventing HIV infection.

The discussion was organized by The Committee on Human Rights, Minorities, and Racial Equality and brought together representatives of pharmaceutical companies, the government, and civil society.

“We are talking about rights,” stated Congresswoman Erika Kokay. “It is not a consumer relationship, it is a relationship of human rights and health that allows the population to take ownership of their own research. We are talking about a country where more than 10,000 people die every year due to AIDS-related illnesses.”

Despite Brazil being one of the countries which participated in the lenacapavir clinical trials (together with Argentina, Mexico, and Peru) it has been excluded from the list of countries that have received a licence to produce its generic version.

“Brazil was excluded from the licence because it is considered a middle-income country, which does not reflect the intense inequalities that exist in Brazil,” pointed out Susana Van der Ploeg, coordinator of Working Group on Intellectual Property. “In 2022, 23% of new HIV infections occurred in countries that were excluded from the licence, including countries that participated in clinical studies,” she added.

According to UNAIDS, Latin America is one of three regions in the world where the annual number of new HIV infections has increased, representing 13% of all new HIV infections between 2010 and 2024.

“When an innovation can save people’s lives but does not reach the people who need it, can we really consider it an innovation?” said Luciana de Melo, HIV/AIDS Coordinator at the Ministry of Health. “Price is a key issue in the incorporation of medicines to the country’s health system”

Cabotegravir, registered by ViiV Healthcare, is an injection administered once every two months to prevent HIV. The drug was approved by the Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) in 2023 and launched on the Brazilian private market in August 2025. Currently, its average cost is R$ 4,000 per dose (U$ 740), around 2,5 times the minimum wage in Brazil. According to Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 31.8% of the population lived on an income between one and three minimum wages in 2023. There is still no date for the drug to be offered through Brazilian health system.

Lenacapavir, from the pharmaceutical company Gilead, is administered once every six months and is in the process of being registered for use in HIV prevention. Gilead has not yet announced the price of the drug to be used for HIV prevention in Brazil but its cost in the United States for treatment was recorded at over US$ 28,000 per person per year.

An article published in The Lancet magazine presents a different perspective for the generic version. The study projects that the cost of generic lenacapavir could range from as low as US$ 35 to US$ 46 per person per year. In addition, growth in demand could reduce this amount to US$ 25 per person per year if there were a committed demand of five to ten million people.

“We will not be able to reach our goals if we do not view access to health as a human right,” said Andrea Boccardi Vidarte, UNAIDS Country Director, Brazil.

Watch the full hearing (in Portuguese): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcBecwT-WzY

Watch the full hearing (in Portuguese)

Region/country

Feature Story

Colombian Afro-descendant women are shaping the HIV response in their own terms

06 August 2025

06 August 2025 06 August 2025This story first appeared in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

In Colombia, Afro-descendant women are taking the HIV response into their own hands. Faced with racism, inequality and violence—factors that make them more vulnerable to HIV—they are organizing themselves, speaking out, and demanding better access to health care, protection and rights.

In the Caribbean and Pacific coastal regions of Colombia, women represent half of all people diagnosed with HIV, compared with only a fifth at the national level. This gap is tied closely to gender inequality and other structural barriers such as violence and poor access to basic health services, including HIV testing and treatment. In addition, stigma—worsened by racism and sexism—makes it harder for many women to get an education, find work or receive proper medical care, leaving them more exposed to the risks of HIV.

Armed conflict and forced displacement have affected communities, exacerbating poverty and exposure to violence, including sexual violence.

UNAIDS, through the help of key donors, supports various organizations leading the HIV response in Afro-Colombian, Indigenous and rural communities. The Fundación Afro Mata ’e Pelo works to improve access to information on sexual and reproductive health in the Caribbean region of Colombia, where myths, stigma, discrimination and gaps in training among health workers remain common challenges.

In the Valle del Cauca department, located along the Pacific coast and within the Andean region, Fundación RedLujo supports transgender women, sex workers and nonbinary people by using artistic and pedagogical strategies to raise awareness about HIV and advocate for inclusive public policies that guarantee access to HIV prevention and care.

These organizations are bringing change to their communities, taking the lead in the response to HIV and pushing for fair, respectful access to health care. They work with Colombian Government institutions to make sure HIV prevention and care policies reflect local realities and include the voices and needs of communities.

“It is a challenge to make women visible, especially in the contexts and territories where Black and Indigenous women live,” says Yaneth Valencia, HIV activist and founder of the Asociación Lila Mujer, a community-based organization focusing on women in southwestern Colombia. Through their sessions, women learn about HIV prevention and share their experiences. The organization advocates for better access to services and promotes the participation of women as agents of change in their territories.

“These spaces of sisterhood—of comadreo, as we call them in the communities—allow us to talk with our comadres. These can be self-help groups or peer advisors with whom we can talk and trust. It is also about recovering all that ancestry that allows us to reconnect and resist because we not only exist—we resist in a macho, racist, classist and very white context.”

Afro-descendant women are leading community efforts in Colombia to respond to HIV with a focus on human rights. They are ensuring the response meets the real needs of their communities. Their work gives a voice to people often left out of HIV efforts and defends their right to health and dignity.

Global AIDS update 2025

Region/country

Feature Story

Empowering young women in Cité Soleil: a model for reducing vulnerability to violence in Haiti

08 August 2025

08 August 2025 08 August 2025This story first appeared in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

Gang violence in Haiti is contributing to a dire humanitarian crisis in a country where 5.7 million people face acute food insecurity and more than a million people are internally displaced, half of them children. In the country’s capital of Port-au-Prince, only 50% of healthcare facilities are operational, and access to essential health services, including HIV treatment, is severely limited. Amidst the escalating insecurity, ruthless sexual violence, including gang rape, is rampant, exacerbated by restricted or suspended gender-based violence services.

More than 6500 incidents of gender-based violence were reported in 2024, although this number is likely to be significantly underreported. Nearly two-thirds of these incidents involved rape or sexual assault. Between 2023 and 2024, there was a shocking 1000% increase in sexual violence against children.

“I was a victim of gang rape in 2021,” says 29-year-old Laguerre Myrline. “This happened when we had to abandon our home to flee the attacks of armed men. At the southern entrance of Port-au-Prince, I was assaulted by several men. They abused me one after the other. Traumatized, I didn’t even go to the hospital.”

Women and children remain particularly at risk in this crisis. The Organization for Development and Poverty Reduction (ODELPA), a civil society organization supported by UNAIDS and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is implementing a transformative initiative aimed at reducing sexual and gender-based violence and other systematic violence in Cité Soleil, an impoverished and densely populated commune in Port-au-Prince.

The initiative includes capacity building and economic empowerment via training on HIV prevention, prevention of gender-based violence and mental health support for girls, young women and men. Through these efforts, 180 beneficiaries have received startup funds to launch income-generating activities and businesses, helping them to break the cycle of financial dependence and offering a sustainable pathway to resilience and autonomy.

The programme has been so successful that the training sessions have been replicated for more than 1000 members of grassroots community organizations. In addition, ODELPA launched a multimedia communication campaign to raise awareness and provide education on prevention of gender-based violence.

The campaign reached more than 1.5 million people across Haiti and the Haitian diaspora through four radio programmes. The project applies a holistic approach that combines education, economic empowerment and community-driven solutions as key elements to breaking cycles of violence and inequality and ensuring girls and young women can reclaim their rights and dignity and their future.

In Haiti, the recent funding cuts have had a huge effect on the national HIV response, which was almost 100% funded externally and almost entirely reliant on PEPFAR (which provided about 90% of HIV funding) and the Global Fund (which contributed the remaining 10% of funding). Civil society organizations have been significantly impacted by the funding cuts, particularly those that provide services for people from key, priority and vulnerable populations. This has increased vulnerability to stigma, discrimination and gender inequality, and weakened responses to sexual and gender-based violence.

The youth project implemented by ODELPA and supported by UNAIDS and UNHCR is a small beacon of hope. Sustainable funding will be required to support the response to HIV in Haiti, including urgent renewed global solidarity

Global AIDS update 2025

Region/country

Related

Impact of US funding freeze on HIV programmes in Haiti

Impact of US funding freeze on HIV programmes in Haiti

13 March 2025

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

19 February 2025

Feature Story

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025

11 August 2025 11 August 2025This story first appeared in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

In early 2022, shortly after the full-scale invasion of eastern Ukraine, Kateryna was pregnant and caring for her young son and daughter.

“We lived under constant shelling in Pokrovsk. For the sake of my children, I had to flee to give birth,” she says. She is originally from the Donetsk region in Ukraine, which by 2024 became the scene of intense fighting.

Today, her hometown of Pokrovsk lies in ruins. With three children and no home to return to, Kateryna is trying to rebuild her life from scratch.

Kateryna has found refuge in the city of Dnipro at a shelter run by the non-governmental organization 100% Life was established by UNAIDS with donor support. The shelter provides a safe environment for women living with HIV, including those with children. It is one of four such shelters in the Dnipropetrovsk region, offering vital humanitarian assistance and connections to HIV care for people who have lost everything.

Since the beginning of the war, nearly 3.7 million people have been displaced within Ukraine. As the violence has escalated and people are forced to flee repeatedly, many people are living in areas of active fighting or under occupation. In this context, any reliable assessment of the rate of HIV among displaced people is impossible.

Despite this, the health system in Ukraine, supported by humanitarian organizations and international donors, has made extraordinary efforts to ensure continued access to HIV treatment. From the first days of the invasion, the Public Health Center quickly distributed antiretroviral medicines to central and western regions, where most internally displaced people fled. Emergency stocks were concentrated in leading health facilities and, with the help of nongovernmental organizations, volunteers and partners, supply chains were rapidly restored.

“In the early days of the war, hospitals in Lviv were overcrowded,” says Olenka Pavlyshyn, an infectious diseases specialist at the Center for Integrated Medical and Social Services. “But even then, there were no interruptions in antiretroviral therapy.” People received three- or six-month supplies of medicines, and treatment was provided based on medical need rather than documents or place of residence.

The response also reached people who fled abroad. A total of 6.4 million Ukrainians have left the country, and many face barriers to health care in host countries. “In some European countries, our citizens still cannot get health insurance, so they have no access to medical care,” says Olenka. “Others are not ready to disclose their HIV status in a new environment, so these people come back to Ukraine every six months—and we give them the medicines they need for continued treatment while living abroad.”

As the health system in Ukraine adapts to the demands of a displaced population inside the country and beyond its borders, pressure is growing.

Ukraine was once a regional leader in transitioning from donor to domestic funding for health services, but its HIV resources are extremely constrained due to the war. The country now relies heavily on international assistance to sustain essential medical care, including HIV services. Although antiretroviral therapy has been secured, HIV services may be at risk due to cuts in United States funding.

New HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths could rebound globally if the funding cuts are not recovered. Continued international support is critical to sustain the HIV response and ensure countless people caught in a war, like Kateryna, are not left behind.

Global AIDS update 2025

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Community workers at the heart of a resilient HIV response in Ethiopia

04 August 2025

04 August 2025 04 August 2025This story first appeared in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

Amhara in northern Ethiopia is a region with a rich cultural history. The birthplace of the national language, Amharic, it is home to ancient churches such as the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Lalibela. In April 2023, the region was plunged into crisis when internal armed conflict erupted. The consequences were devastating.

Thousands of people were displaced, gender-based violence surged, essential services such as health and education were disrupted, and travel between cities became almost impossible.

As formal systems broke down, local community-based organizations and drop-in centres in urban areas such as the regional capital Bahir Dar continued to monitor the situation on the ground and provide vital services. These organizations became lifelines for people living with HIV, people from key populations and young people.

This changed in February 2025. Cuts in United States funding disrupted essential services. Many community-run organizations that relied on those funds were forced to close. Outreach workers who had built trust with people on their doorsteps were suddenly laid off. Peer support groups vanished. Fear took hold.

“I often find myself overwhelmed with stress,” says a member of one women-led association of people living with HIV. “If medicine and other services stop, where will I go? I simply do not have the means to afford the treatment I need.”

The data collected by the association paint a stark picture. For two months, no new clients have been enrolled in PrEP. “One of my biggest concerns is not having access to condoms,” says a case manager. “Without them, HIV will spread much more easily.”

She adds, “Without a financial budget, our members are left without the basics, no food, medical care, transportation, no hope. They have families. They rely heavily on this support. It would make a huge difference if members could access free medical treatment and hospital services. Many cannot even afford one meal a day. Their health is deteriorating. Their children are suffering. What they need most is dignity, food and a fighting chance.”

Yet even when faced with collapse, communities refused to give up. Young volunteers formed informal networks and WhatsApp groups to check on peers and stay connected. Mothers banded together to support children’s treatment. Youth collectives used community radio and shared airtime to spread critical health information.

Where formal systems failed, communities built their own safety nets.

The situation in Bahir Dar was a wake-up call. It exposed the fragility of systems dependent on a single funding source.

This crisis shows that resilience must be built into HIV responses from the start. Community-led and youth-driven responses must be recognized, resourced and scaled up. UNAIDS is providing support to community organizations to access funding support from local government authorities and private foundations to empower them to continue this important work of community outreach to the most vulnerable populations.

The conflict in the region has shown once again that HIV must feature in humanitarian, development and recovery agendas. The intertwined challenges of conflict, displacement, gender-based violence and HIV demand integrated, person-centred solutions. This will not happen if HIV is treated as an afterthought or is equated only with clinical care and if community-engagement is not recognized and supported.

Global AIDS update 2025

Region/country

Feature Story

Using sports to combat gender stereotypes and learn about HIV

30 July 2025

30 July 2025 30 July 2025This story first appeared in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

Marouane Abouzid grew up in Casablanca, Morocco, where many boys act like bullies and sex is taboo. That changed when he joined the project Sport Is Your Protection, where he gained knowledge about gender equality and health. “The training on HIV awareness led by UNAIDS and Tibu Africa was a transformative experience in the sense that I saw how sports can be an effective way to get a message out,” the 25-year-old says. “It also gave me essential skills like communicating clearly and active listening.”

He enjoyed the project so much that he trained to lead sports activities and participate in other sessions. “I talk openly about what I have learned. I encourage my friends to get tested for HIV and encourage people to respect others,” he says, excited about becoming a role model for his peers.

Marouane describes the activities as a safe space to discuss all sorts of issues that young people face in Morocco, such as poverty, unemployment and a patriarchal system.

Marouane is not alone. Assia Ezzahraoui, a participant in the Tibu Africa sports vocational school programme, joined the weeklong sexual education awareness meeting. “The informative sessions gave me new insights into symptoms, prevention methods and available treatments,” she says. Assia feels more secure about how to protect herself and her friends.

Tibu Africa was founded in 2011 and aims to bring the programme across different cities in Morocco. UNAIDS joined with Tibu Africa in 2024. “This first partnership with UNAIDS Morocco mobilized young people around issues to transcend barriers and create opportunities for dialogue and awareness,” says Mohamed Amine Zariat, President of Tibu Africa. “We hope this first step will serve as a springboard for future, even more ambitious initiatives.”

An estimated 24 000 [21 000–26 000] people are living with HIV in Morocco, and nearly 40% of these are women. Although the prevalence of HIV is relatively low in Morocco, vulnerable populations such as sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs are particularly at risk. Moroccan youth represent more than 30% of the total population, but a quarter of people aged 15–24 years have no job and lack education and training—young women are particularly hard hit.

Houssine El Rhilani, UNAIDS Country Director in Morocco, is aware of this. He believes the collaboration with Tibu Africa combining sport, education and awareness-raising can empower young people. “We were able to reach young people not only with information, but also through experience, providing them with concrete tools to become prevention ambassadors in their own communities,” he says. “We cannot end AIDS without prioritizing future generations.”