Feature Story

Hope from Tiraspol

06 January 2021

06 January 2021 06 January 2021Nadezhda Kilar’s battles with her health service providers began several years ago. “I did not agree with how obstetrics services for women living with HIV are provided in our city,” said Ms Kilar. “From admission to discharge, there was a constant violation of rights.”

Ms Kilar, who lives in Tiraspol, in the Republic of Moldova, has been living with HIV for several years. Her antiretroviral therapy has suppressed her viral load to undetectable levels, but during pregnancy and childbirth she was isolated. She was kept in an isolation ward, gave birth in a separate delivery room and after giving birth was placed in a special room for women living with HIV—a room with bars on the window.

“All the other women leave through the front door, where relatives meet them with flowers and a photographer. But I was let out through the back exit, where there are garbage cans,” she said.

And the discrimination did not stop with her. “Although my son does not have HIV, in the maternity hospital he was alone in a separate special room, under a sign with “HIV contact” written on. Why should a child feel this stigma?” Ms Kilar said.

“I want to give birth to my next child in a normal maternity hospital. And I do not doubt that it will be so. For something to change, a lot still needs to be done, but the main thing is I must defend my rights,” she said.

Ms Kilar’s relationship with her husband started to break down after he became violent towards her. For a long time, she didn’t do anything about it, as she thought that violence was the norm. “My father often beat my mother; I myself was twice in hospital after his beatings.” Not knowing what to do, she sank deeper and deeper into depression. “I didn’t want to live,” she said.

But change slowly came about. When she realized that she could not cope with her financial problems, the violence and her depression, on the advice of a peer consultant at the HIV clinic she attends in Tiraspol she joined the Women’s Mentoring Programme, along with 20 other women living with HIV from different communities in the area. The Women’s Mentoring Programme, a joint project of UN Women and UNAIDS and supported by the Government of Sweden, works through peer consultants and mentors to help women living with HIV to understand and identify their problems, learn about their rights and get support in the fight against violence and discrimination.

“I understood that it would not be the same as before. I realized that I would not tolerate the beatings,” Ms Kilar said.

Since 2019, Ms Kilar has been working in a sales job and has been studying at the university to become a teacher. “It’s not easy for me. I do not sleep much at night, but I have gained confidence that I can solve problems on my own,” she said.

Iren Goryachaya, the Programme Coordinator for the Women’s Mentoring Programme, explained that the programme provides a range of services. “We not only deal with the issues of discrimination in a health-care institution or the fight against violence—we see a woman as a person from different perspectives. First, it is important to help women accept their HIV status and overcome self-stigma. Without this, it is impossible to achieve a different attitude towards herself either from doctors or men.”

“Often, women in the Republic of Moldova have insufficient access to reliable information about HIV. They still cannot defend their right to safe sex. Various forms of violence, including sexual violence, the widespread violation of women’s rights and the controlling behaviour of men further aggravate the situation. All this deprives women of the opportunity to defend their right to health,” said Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Representative for the Republic of Moldova.

Ms Kilar looks to the future with confidence. “I see myself as a free woman. I do what I want. My children are growing up in a safe environment. I don't worry about my HIV diagnosis. If I decide to have another child, I will give birth in a normal hospital.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025

Feature Story

Y+ Global launches COVID-19 fund to support young people living with HIV

05 January 2021

05 January 2021 05 January 2021Communities of people living with HIV have been at the forefront of the community-led response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of that response, the Global Network of Young People Living with HIV (Y+ Global), with support from UNAIDS, has launched the Y+ Social Aid Fund for young people living with HIV.

The Y+ Social Aid Fund will be piloted in Nigeria and Malawi, where, with the support of national networks of young people living with HIV ,Y+ Global will offer financial support to young people living with HIV who have been impacted by COVID-19-related restrictions.

“Lockdowns, social instability and treatment interruptions during COVID-19 have further magnified the inequalities that exist in the societies of young people. With grants such as the Y+ Social Aid Fund, young people living with HIV will be able to access basic living essentials that will relieve a portion of the burden on their mental health,” said Igor Kuchin, the Y+ Global Board Chair.

COVID-19 and associated restrictions have had a severe negative impact on the lives of young people living with HIV. Adolescent girls and young women living with HIV are experiencing issues ranging from poor access to menstrual hygiene products to increased need for refuge from gender-based violence while in lockdown. In the 2020 World AIDS Day report, Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the centre, 27 out of 28 countries surveyed reported that COVID-19 restrictions were impacting antiretroviral therapy initiation for people newly diagnosed with HIV.

“In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, communities of young people living with HIV are once again leading responses and providing new examples of the solidarity, resilience and innovation that have driven and accelerated the HIV response since the beginning of the HIV pandemic,” said Suki Beavers, Director of the UNAIDS Department for Gender Equality, Human Rights and Community Engagement.

It is hoped that this initial roll-out to provide financial assistance to the most vulnerable young people living with HIV globally will be scaled up. UNAIDS is encouraging other partners and funders to support the scale-up of the Y+ Social Aid Fund in order to ensure that more young people living with HIV are able to access health care and other services during the COVID-19 crisis and beyond.

Our work

Feature Story

Coming together to address the cost of inequality

15 December 2020

15 December 2020 15 December 2020“My business suffered because of corona. Before corona, I would sell at least 10 egg trays a week. At the height of the pandemic, I was lucky if I could sell two trays,” lamented George Richard Mbogo, who is living with HIV, a father of two, and owns a chicken, egg and chips business in Temeke, a district in the southern part of Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania.

The COVID-19 crisis has adversely impacted the livelihoods of people living with HIV in the United Republic of Tanzania, exacerbating the challenges they face. These include HIV service delivery and widening social and economic inequalities.

“Corona has been a very difficult time. I lived with a lot of worry and stress. Driving a bodaboda (motorbike taxi) requires going into crowds and working closely with people. It has been difficult not to fall into anxiety and depression, balancing getting my HIV treatment and work. I had moments thinking of stopping taking my meds, but I didn’t,” said Aziz Lai, a motorcycle driver who also lives in Dar es Salaam.

Although the colliding pandemics of HIV and COVID-19 are hitting the poorest and the most vulnerable the hardest, through national resource mobilization the COVID-19 crisis has created an opportunity for partners to mobilize in support of the communities they serve.

The collaborative efforts between the government, development partners, including the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, USAID and UNAIDS, the National Council of People Living with HIV (NACOPHA) and community activists have been key in responding to COVID-19, providing information, services, social protection and hope to people living with HIV during these unprecedented and trying times.

One such initiative is Hebu Tuyajenge, run by NACOPHA and funded by USAID, which focuses on increasing the utilization of HIV testing, treatment and family planning services among adolescents and people living with HIV, strengthening the capacity of community organizations and structures and improving the enabling environment for the HIV response through empowering people living with HIV.

Caroline Damiani is a single mother of three who is living with HIV and keeps chicken and ducks for a living. “Hebu Tuyajenge gave us personal protective equipment, sanitizers, soap and buckets and education about COVID-19 and how to take care of ourselves in order to stay healthy during the pandemic,” she said.

Through community-based services that supplement facility-based care, people living with HIV have been linked to and kept on treatment during the crisis by critical peer-to-peer HIV services.

For Elizabeth Vicent Sangu, who has been living with HIV for 26 years, her “numbers” speak for themselves.

“From my community follow-ups, I have returned 80 people to the clinic for CD4 count testing, inspired 240 people to get tests, reported 15 gender-based violence cases and provided education to 33 groups, including youth and church groups,” she said, beaming with pride.

NACOPHA helped Ms Sangu to come to terms with her status and helped her on her own journey of self-empowerment.

“Since becoming a treatment advocate for Hebu Tuyajenge, I have received help with entrepreneurship and education about HIV. I have become a teacher for others. I have made others brave about living with HIV and getting tested,” she said.

The partnership between community advocates and health facilities has paid off.

“Both we and our patients were fearful initially, but due to information and education, things got better. We focused on providing hourly and daily information to patients about corona and made sure that people practised safe social distancing,” said Rose Mwamtobe, a doctor at the Tambukareli Care and Treatment Centre in Temeke.

“Not only in the United Republic of Tanzania, but globally, COVID-19 is showing once again the cost of inequality. Global health, including the AIDS response, is interlinked with human rights, gender equality, social protection and economic growth,” said Leopold Zekeng, UNAIDS Country Director for the United Republic of Tanzania.

“The key to ending AIDS and COVID-19 is for all partners to come together, on a country and global level, to ensure that we leave no one behind,” he said.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

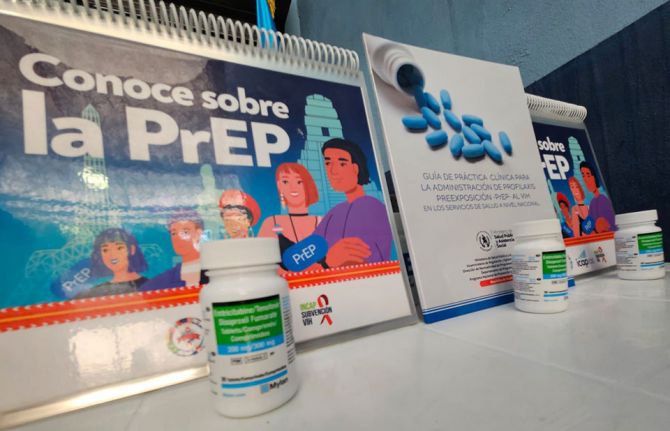

Lima joins the Fast-Track cities initiative

18 December 2020

18 December 2020 18 December 2020When Lima celebrated this year’s World AIDS Day, the Mayor, Jorge Muñoz, decided to go beyond the traditional lighting of buildings and participation in official events to mark the day. By signing the Paris Declaration to end the AIDS epidemic in cities, he joined the Fast-Track cities initiative, a network of more than 300 municipalities around the world, 70 of which are in Latin America and the Caribbean, and committed to ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030.

Lima has a population of more than 10 million people and accounts for around one third of the national population. Lima and the two other Peruvian municipalities that have already signed the Paris Declaration, Callao and La Victoria, accounted for around 50% of all new HIV infections in the country in 2019.

“Through this public commitment, the city of Lima pledges to carry out the necessary actions to accelerate the response to AIDS, including education, awareness-raising and non-discrimination campaigns,” said Mr Muñoz during the signing ceremony. “We will also implement a work plan to train health personnel and promote access to information and sex education.”

“With the signature of the Paris Declaration, the city has committed to eliminate stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and key populations, scale up HIV prevention services and contribute to achieving national targets to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals,” said Andrea Boccardi, the UNAIDS Country Director and Representative for Peru, Ecuador and the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

This is not the first time that Mr Muñoz has taken action against discrimination. In May 2019, when he was the Mayor of the city of Miraflores, he established an ordinance that prohibited discrimination in all its forms in the public and private spheres of the district. Now, as the Mayor of Lima, he has extended that policy to the entire province.

On 1 December 2014, mayors from around the world met in Paris to launch the Fast-Track cities initiative and pledged to adopt a series of commitments to accelerate their response to HIV, with the aim of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Besides committing to ending the AIDS epidemic at the municipal level and uniting as leaders, the signatories also commit to putting people at the centre, addressing the causes of risk, vulnerability and transmission of HIV, using the AIDS response for positive social transformation, building and accelerating appropriate responses reflecting local needs, and mobilizing resources for integrated public health and sustainable development.

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

Navigating Lesotho’s legal system to address gender-based violence

08 March 2021

08 March 2021 08 March 2021When Lineo Tsikoane gave birth to her daughter, she was inspired to intensify her advocacy for gender equality to give Nairasha a better life as a girl growing up in Lesotho.

“I think a big light went off in my head to say, “What if the world that I’m going to leave will not be as pure as I imagine?” I ask myself, “What kind of world do I want to leave my daughter in?”” she says.

As a result, Ms Tsikoane champions for women’s social, economic and legal empowerment at her firm, Nairasha Legal Support. It offers legal support for women in small and medium enterprises and women who are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

“Our main focus is gender-based violence, because this happens to be a country that has one of the highest incidences of rape and intimate partner crime in the world,” she says.

Even before the COVID-19 outbreak, violence against women and girls had reached epidemic proportions globally.

According to UN Women, 243 million women and girls worldwide were abused by an intimate partner in the past year. In Lesotho, it is one in three women and girls.

Less than 40% of women who experience violence report it or seek help.

As countries implemented lockdown measures to stop the spread of the coronavirus, violence against women, especially domestic violence, intensified—in some countries, calls to helplines increased fivefold.

In others, formal reports of domestic violence have decreased as survivors find it harder to seek help and access support through the regular channels. School closures and economic strains left women and girls poorer, out of school and out of jobs, and more vulnerable to exploitation, abuse, forced marriage and harassment.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) works together with UNAIDS, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization on 2gether4SRHR, a joint programme funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, to address HIV and sexual and reproductive health in Lesotho.

During Lesotho’s lockdowns, UNFPA worked with Gender Links, the Lesotho Mobile Police Service and others to support efforts to prevent and respond to incidences of gender-based violence.

“We are ensuring that a helpline, where people experiencing gender-based violence can call, is in place and is working and we are also providing relevant information through various platforms for people to access all the information they need on gender-based violence,” says Manthabeleng Mabetha, the UNFPA Country Director for Lesotho.

Mantau Kolisang, a local policeman from Quthing, Lesotho’s southernmost district, characterized by rolling hills and vast landscapes, says one reason why gender-based violence is prevalent in Lesotho is because the law is not heeded in the rural areas.

“It’s difficult to implement the law since these are remote areas,” he says, adding that while he has made arrests, he has no transport to access far-flung areas in the small mountainous region.

Lesotho’s law states that a girl can marry at the age of 16 years. However, Mr Kolisang says cultural practices, coupled with contraventions of the law, has made some men believe a 13-year-old girl “can be a wife”, exposing Basotho girls to violence.

“Men don’t regard it as a crime,” he says, adding that girls have been abducted from the mountains for forced marriages.

Between 2013 and 2019, 35% of adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa were married before the age of 18 years. Girls married before 18 years of age are more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those married after the age of 18.

Because of poverty, gender inequality, harmful practices (such as child, early or forced marriage), poor infrastructure and gender-based violence, girls are denied access to education, one of the strongest predictors of good health and well-being in women and their children.

In Lesotho’s legal system, women are regarded as perpetual minors. This categorization infantilizes women, Ms Tsikoane says. A man who abuses a woman can often walk away unscathed from the justice system if he says the woman in question is his “wife”, she adds.

“This makes women vulnerable to commodification because a child can be passed around,” she says.

Ms Tsikoane says there is a direct link between the minority status of women and HIV infection in Lesotho. In 2019, there were 190 000 women 15 years and older living with HIV in Lesotho, compared to 130 000 men.

Adolescent girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 24 years are particularly vulnerable. They accounted for a quarter of the 11 000 new HIV infections in Lesotho in 2019.

“My hypothesis is women cannot negotiate safe sex,” says Ms Tsikoane.

The dangerous reality that Basotho women live in worries Mr Kolisang. But due to a lack of institutional support and resources, he feels his actions have limited effect.

“I feel for these children. I feel for these women. I do feel for them. I can help, but the problem is how?” he laments.

Ms Tsikoane says she finds “trinkets of opportunities” for her and her colleagues to help their clients and navigate a legal system that is not favourable towards women.

“So, if you are not being well assisted at a police station, if you feel like someone is dragging your case and you are struggling to get an audience, we are there. We will support you and we will fight with you,” she says.

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

PrEP in the City: campaign for transgender women aims to increase PrEP uptake in Thailand

09 December 2020

09 December 2020 09 December 2020Rena Janamnuaysook steps off the Skytrain in Bangkok’s bustling Sukhumvit shopping district. She looks up, filled with a sense of joy as her eye catches an advert just beyond the platform. The advert is promoting the PrEP in the City campaign to raise awareness and increase the uptake of PrEP among Thai transgender women and shows glimpses of the lives of four transgender women as they juggle their busy work schedules, their role as a mother and their relationship with loved ones, all the while taking control of their health with their daily dose of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). For Ms Janamnuaysook, a transgender advocate and Program Manager for Transgender Health at the Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI), this first-ever PrEP campaign for transgender women in Thailand signals promise for the country’s HIV response.

“PrEP campaigns of the past were only targeting other key populations, especially men who have sex with men and gay men. Transgender women were left out from PrEP campaigns or public messages,” says Ms Janamnuaysook.

HIV prevalence among transgender people in Thailand was estimated to be 11% in 2018, with no sign of a decline in the past few years, and the current uptake of PrEP among transgender women is only 7%, making the group a particularly at-risk population. Less than half (42%) of transgender people reported that they are aware of their HIV status, while services catering to their specific needs are limited.

Limited awareness and knowledge about PrEP contribute to the low uptake. The campaign strategy includes reframing the conversation on PrEP use and challenging negative perceptions of PrEP within the transgender population. “For transgender women who know about PrEP already, they still don't want to get it because it has been associated with risky behaviour or negative behaviour. In Thai society, if you use PrEP then you are perceived to have multiple partners, be a sex worker or must have unprotected sex,” says Ms Janamnuaysook.

Ms Note, a client at the Tangerine Clinic, South East Asia’s first transgender-specific sexual health clinic that offers gender-affirming integrated health care and PrEP, among many other health services, speaks of the perception of PrEP, saying, “I had to be cautious so that nobody sees me taking the pills because sometimes people are worried and think that I am sick.” A goal of the campaign is to normalize the use of PrEP and promote continued use, particularly important when evidence suggests that nearly half of transgender women (46%) in Thailand did not return for their one-month visit after starting PrEP.

“The campaign makes taking PrEP seem similar to taking vitamins or supplements for good health. It removes the image that PrEP is suitable for only certain groups, when in fact it can be taken by anybody,” said Ms Note.

Adverts for the campaign are on billboards across Bangkok, illustrative of the collaboration with the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and the commitment to achieve the city’s Fast-Track Targets. Online, IHRI has enlisted various social media influencers, bloggers and opinion leaders in the transgender community to share information about the campaign.

“I personally feel proud to have participated in this campaign, which makes people see the other sides of us, transgender women, and our potentials,” says Jiratchaya (Mo) Sirimongkolnavin, a model and beauty blogger featured in the campaign, who is a former winner of Miss International Queen, one of the world’s largest transgender beauty pageants. She goes on to explain, “It encourages people to have general conversations about sex and how to protect themselves from HIV infection.”

Promoting positive representations of Thai transgender women is an underlying focus of the campaign. “I think the story in the video will help wider audiences to see the diversity among transgender people that actually exists in today’s society,” said Ms Note. “The fact that transgenders have many occupations and abilities.”

At a launch event for the campaign, Satit Pitutecha, Deputy Minister of Public Health, spoke about the government’s commitment to strengthening the HIV response, stating, “The Ministry of Public Health has committed to working in partnership with communities and civil society to promote access to HIV and other health services for transgender people.”

Ms Janamnuaysook is proud of the buzz that the campaign has catalysed, which has been shared widely in Thailand and in surrounding countries. She hopes that this campaign, with its tailored messaging for transgender women, won’t be the last and believes that it can serve as a model for future campaigns focusing on other key populations.

The PrEP in the City campaign was developed by IHRI and is supported by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the United States Agency for International Development’s LINKAGES Thailand Project, managed by FHI 360 and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, the Division of AIDS and STIs of the Ministry of Public Health and the UNAIDS Asia–Pacific Office.

Feature Story

Snapshots on how UNAIDS is supporting the HIV response during COVID-19

03 December 2020

03 December 2020 03 December 2020From the very beginning of the pandemic, UNAIDS has been helping people living with and affected by HIV to withstand the impacts of COVID-19.

In January and February, when COVID-19 forced a lockdown in Wuhan, China, the UNAIDS China Country Office started to receive messages on social media from people living with HIV, expressing their frustration and seeking help.

A survey of people living with HIV in China devised and jointly launched by UNAIDS found in February that the COVID-19 outbreak was having a major impact on the lives of people living with HIV in the country, with nearly a third of people living with HIV reporting that, because of the lockdowns and restrictions on movement in some places in China, they were at risk of running out of their HIV treatment in the coming days.

The lockdowns had also resulted in people living with HIV who had travelled away from their home towns not being able to get back to where they live and access HIV services, including treatment, from their usual health-care providers.

The UNAIDS China Country Office worked with the BaiHuaLin alliance and other community partners to urgently reach the people at risk of running out of their medicines to ensure that they got their medicine refills. By the end of March, special pick-ups and mail deliveries of HIV medicines arranged by UNAIDS had reached more than 6000 people in Wuhan. UNAIDS also donated personal protective equipment to civil society organizations serving people living with HIV, hospitals and others to help in the very early stages of the outbreak.

But the UNAIDS China Country Office didn’t just help people in China. Liu Jie, the Community Mobilization Officer in the UNAIDS Country Office in China, was surprised when she had a call from Poland in March. “A Chinese man introduced himself, saying he is stranded and will run out of HIV medicine in two days,” she said.

With travel restrictions closing down more and more countries, the man could neither return home nor access medicine. Not knowing what to do, he reached out to a Chinese community-based organization and through it contacted UNAIDS in Beijing. A series of phone calls later and the National AIDS Center in Poland followed up—24 hours later, Ms Liu received a photo of the same man who called her, holding up a box of HIV medicine.

The man stuck in Poland wasn’t the only example of UNAIDS helping individuals to get the treatment they needed. By May, UNAIDS had helped hundreds of stranded people to obtain HIV medicine in countries around the world.

A day before Deepak Sing (not his real name) planned to return to India, all international travel ground to a halt, and he was stuck in Luanda, Angola. “I visited more than 10 pharmacies and explored options of delivery of antiretroviral medicines from India to Angola, but without success,” he said. The UNAIDS Country Director for Angola guided Mr Sing towards the national AIDS institute in Angola, which organized a conference call with a medical doctor because one of the medicines that Mr Sing took is not yet in use in the country. The doctor proposed a substitute and in less than 24 hours he picked up his medication.

It was realized early on in the COVID-19 pandemic that one way of ensuring that people on HIV treatment can continue to access their medicines, and to avoid the risk of transmission of the new coronavirus, was to ensure that people living with HIV got multimonth supplies of their treatment.

An early adopter of multimonth dispensing was Thailand, which announced in late March that it would dipense antiretroviral therapy in three- to six-month doses to the beneficiaries of the Social Security Insurance Scheme. After the decision, UNAIDS worked closely with the Ministry of Public Health and partners to advocate for the adaptation of the same policy for all health insurance schemes.

UNAIDS has supported countries worldwide to ensure that people living with HIV access multiple-month supplies of HIV treatment. For example, in Senegal in May, weaknesses in the supply chain, including inadequate assessments of the needs at some clinics for supplies of antiretroviral therapy and irregular supplies centrally, meant that not all people who needed such supplies got them. UNAIDS supported the government in tracking orders of antiretroviral medicines and in strengthening the supply chain.

A modelling group convened by the World Health Organization and UNAIDS estimated in May that if efforts were not made to mitigate and overcome interruptions in health services and supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to more than 500 000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses and that gains made in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV could be reversed, with new HIV infections among children up by as much as 162%.

The physical distancing and hygiene recommendations to counter the new coronavirus are particularly difficult for some communities to follow. In April, the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern and Southern Africa and Reckitt Benckiser joined forces to distribute more than 195 000 hygiene packs to people living with HIV in the eastern and southern African region. Each pack consisted of a three-month supply of Dettol soap and Jik surface cleaner and was distributed in 19 countries through UNAIDS country offices and networks of people living with HIV as part of efforts to reduce exposure to the impact of COVID-19 among people living with HIV.

Kyrgyzstan saw a state of emergency imposed on some regions in March, which resulted in a loss of earnings for many people. The UNAIDS Country Office in Kyrgyzstan, with the support of a Russian technical assistance programme, organized the delivery of food packages for the families of people living with HIV, along with colouring books, marker pens and watercolour sets for the children of people living with HIV, to help them get through the lockdown. “We hope that this small help will go some way to enabling people living with HIV to remain on treatment,” said the UNAIDS Country Manager for Kyrgyzstan at the time.

The UNAIDS Country Office for Angola leveraged its partnerships to reach thousands of people in Luanda with food baskets. UNAIDS and partners provided support to women who inject drugs in camps and settlements in Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania, while a partnership that included UNAIDS provided cash transfer to vulnerable households in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, for nutrition and food security and basic health kits.

Members of key populations and people living with HIV have been particularly impacted by the response to COVID-19. UNAIDS has supported the rights of gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, people who inject drugs and prisoners throughout the pandemic.

The Global Network of Sex Work Projects and UNAIDS in April called on countries to take immediate, critical action to protect the health and rights of sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. UNAIDS embarked on a project with the Caribbean Sex Work Coalition to help national networks address sex workers’ knowledge, HIV prevention and social support needs during COVID-19. “Sex workers need to be included in national social protection schemes and many of them need emergency financial support,” said the Director of the UNAIDS Caribbean Sub-Regional Office.

UNAIDS Jamaica provided financial support to ensure that Transwave, a transgender rights organization, had personal protective equipment and to supplement care package supplies and ensured that transgender issues are included in the coordinated HIV civil society response to COVID-19 in the country. “COVID-19 has laid bare just how vulnerable people are when they do not have equitable access to opportunities, justice and health care,” said UNAIDS Jamaica’s Community Mobilization Adviser. “That’s why it’s so important and inspiring that Transwave has continued its core work through all this.”

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, UNAIDS has repeated the call that governments must protect human rights and prevent and address gender-based violence. In June, UNAIDS published a report highlighting six critical actions to put gender equality at the centre of COVID-19 responses, showing how governments can confront the gendered and discriminatory impacts of COVID-19.

“Just as HIV has held up a mirror to inequalities and injustices, the COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on the discrimination that women and girls battle against every day of their lives,” said Winnie Byanyima, the Executive Director of UNAIDS, on the launch of the report.

In August, UNAIDS urged governments to protect the most vulnerable, particularly key populations at higher risk of HIV, in a report intended to help governments to take positive steps to respond to human rights concerns in the evolving context of COVID-19.

In the next month, UNAIDS issued a report that shows how countries grappling with COVID-19 are using the experience and infrastructure from the AIDS response to ensure a more robust response to both pandemics.

In October, UNAIDS issued guidance on reducing stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 responses. Drawing on 40 years of experience from the AIDS response, the guidance was based on the latest evidence on what works to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination and applies it to COVID-19. As with the HIV epidemic, stigma and discrimination can significantly undermine responses to COVID-19. People who have internalized stigma or anticipate stigmatizing attitudes are more likely to avoid health-care services and are less likely to get tested or admit to symptoms, ultimately sending the pandemic underground.

Looking to the future, UNAIDS joined the call for a COVID-19 People’s Vaccine—a vaccine that is affordable and available to all.

Our work

Feature Story

Dakar addiction centre reaches out to women

04 December 2020

04 December 2020 04 December 2020The Centre de Prise en Charge Intégrée des Addictions de Dakar (CEPIAD), which opened in December 2014, is an addiction reference centre in Dakar for Senegal and the wider region. To date, it has cared for 1200 people, including approximately 250 people currently enrolled on its opioid substitution therapy programme.

In Senegal, HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs is 3.7%, well above the average of 0.4% among the general population. HIV prevalence is higher among female drug users (13%) than among men (3%), but women represent less than 10% of CEPIAD’s active caseload. In response, CEPIAD has reached out to women who inject drugs. With the support of UNAIDS, and in collaboration with the Conseil National De Lutte Contre le Sida, CEPIAD organized a week of activities around World AIDS Day to address the specific needs of women.

“Women were at the heart of the organization of this week. We want to remove the misrepresentations and misunderstandings that hinder their attendance at the centre,” said Ibrahima Ndiaye, Deputy Coordinator of CEPIAD.

Women were able to access HIV and hepatitis C screening services, gynaecology consultations, including cervical cancer screening, and addiction counselling. Talks with female drug users and a debate on harm reduction were organized on 1 December, World AIDS Day.

A three-day training on making soap, using honey, aloe vera, shea butter, palm oil and mbeurbeuf, and a batik workshop were also offered. More than 50 women participated and the products were sold on the closing day of the week of activities.

Ndeye Khady, the founder of the batik workshop, is a former crack smoker who is currently accessing opioid substitution therapy and antiretroviral therapy at CEPIAD, where she met her husband, also a former drug user. “My dream now is to have a child. I am so grateful that I have been able to take advantage of the services offered. I encourage more women to use them,” she said.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

The shero of Butha-Buthe: Matšeliso Setoko

11 December 2020

11 December 2020 11 December 2020Matšeliso Setoko stands at the gates of Seboche Mission Hospital in Lesotho and points at the high mountain peaks in the distance.

“Some of our patients come from beyond those mountains,” she says. “Some of them will walk for two hours before they find a taxi, then will ride in the taxi for another three hours before they get here. Some come on horseback.”

Seboche Hospital is located in Butha-Buthe, Lesotho’s northernmost district, in the village of Ha Seboche, accessible only via a winding dirt road with steep twists and turns. Despite its remote location, the hospital has gained a reputation as a centre of excellence since its founding in 1962 and people are willing to travel long distances to go there.

Ms Setoko is the head of the hospital’s antiretroviral therapy clinic and frequently goes out of her way to ensure that her patients have access to their medicines and adhere to their treatment. Lesotho has the second highest HIV prevalence in the world, with an estimated 340 000 people living with HIV. Twelve thousand are children between the ages of 0 and 14 years.

“We often encounter difficult cases,” she explains. “For example, some children have lost their parents, are diagnosed HIV-positive and are chased out of their relatives’ homes when their relatives find out about the diagnosis. In those cases, I go and talk to the relatives to try and understand why they would do such a thing. I find out who the child’s new treatment supporter is and I work closely with him or her to make sure that the child continues to take their medication.”

The arrival of COVID-19 in Lesotho, however, brought a set of challenges unlike anything that Ms Setoko has faced in her 23 years of working at Seboche Hospital.

In the first week of July 2020, a staff member tested positive for COVID-19 and the hospital was forced to shut down for a week. This coincided with the beginning of a nationwide strike by health workers, who demanded that the government provide them with a COVID-19 risk allowance and adequate personal protective equipment. The strike only ended on 27 July.

“Our services were suspended for most of July, but I knew that I had to find a way to help my patients, particularly the children I work with,” says Ms Setoko. “I’m responsible for about 130 children who are on HIV treatment. So, I went to the filing cabinets and took out all their files and found out that many of them needed refills. I went to the pharmacy and got the medication for all of them—enough for three months.”

Ms Setoko then liaised with her colleagues—lay counsellors, nurses and other staff members—to find out who lived in the same villages as her patients. She assembled packages of medicines for each village and asked her colleagues to take them home. She then called all the children’s carers to inform them that their medicine could be picked up from the hospital staff member living in their village.

Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, the borders between Lesotho and South Africa were closed from the end of March to the beginning of October. Many of Ms Setoko’s adult patients are migrant workers in South Africa. Before the onset of COVID-19, her patients would regularly travel from South Africa back to Seboche Hospital to collect their three months’ worth of HIV treatment or would send a relative to pick up their medicine on their behalf. With borders closed, however, many found themselves stuck in South Africa for six months. Again, Ms Setoko had to devise innovative solutions to ensure that her patients did not default on their treatment.

“I think I helped around 50 patients who were in South Africa,” she recalls. “If they were about to run out of antiretroviral therapy, I asked them to identify the clinic closest to them and wrote a referral letter for them. I then took a picture of the letter and sent it to them via WhatsApp or else emailed a PDF copy of the letter to the clinic if that was required. I would also call the nurses at the relevant clinic in South Africa to make sure that my patients received the correct antiretroviral medicines.”

There is a low rate of testing for COVID-19 in Lesotho, with less than 2% of the country’s population having been tested.

“The numbers we are seeing do not give us a true picture of what is happening with COVID-19 in this country,” sighs Ms Setoko. “We are not doing enough testing and it can take weeks for people to get their results. We are also not doing enough contact tracing, so it makes it difficult to contain the spread of the virus.”

In the face of such challenges, Ms Setoko recognizes the value of cooperation and solidarity, both at the community and organizational levels, in efforts to continue with HIV prevention and treatment programmes in the era of COVID-19.

“As Seboche Hospital we are lucky to have the support of other organizations, such as our strong partnership with SolidarMed, a Swiss non-profit organization. We also work closely together as staff from different departments, because when people work together, they can achieve any goal.”

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

The COVID-19 pandemic and women living with HIV: Caroline Damiani

14 December 2020

14 December 2020 14 December 2020Unlike many other countries in the region and the world, no lockdown measures were put in place at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Republic of Tanzania. In June, all restrictions on movement and gatherings were lifted. Nevertheless, the restrictions impacted people’s health and livelihoods, especially those who work in the informal sector, most of whom are women.

Women such as Caroline Damiani, from Chamazi, an administrative ward in the Temeke district of Dar es Salaam.

While, according to the government, about 83% of the 1.7 million people living with HIV in the United Republic of Tanzania are on HIV treatment, this leaves around 300 000 people living with HIV vulnerable. It has been shown that people with underlying health conditions are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 disease.

Thus, COVID-19 is a particular concern for people living with HIV, for both people who are not on HIV treatment and those who are, in ensuring they have access to medicines and health facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic throws into sharp relief existing inequalities, including gender inequality and economic inequality.

In Chamazi, many women make a living selling homemade food, such as buns, fish or ice cream, or selling groceries in small kiosks.

Ms Damiani, a single mother of three, says her business was greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. “Many people no longer wanted to buy my buns or home-made ice cream. I also couldn’t go to the main market to sell because of the crowds and the risk it brought. I then decided to switch completely to selling groceries at a small kiosk and rearing ducks and chickens to sell,” says Ms Damiani.

Ms Damiani has been living with HIV since 1998. All her three children are HIV-negative. Her husband divorced her and married another woman due to her HIV status and pressure from his family. To date, she still does not know his status. She lives with her daughter and granddaughter as her sons each have their own families. Her daily routine now includes feeding her ducks and chickens, helping her granddaughter with her schoolwork, performing household chores and tending her kiosk.

Ms Damiani says the COVID-19 pandemic affected her mental health. “I don’t have many friends and I spend most of my time at home or at the church. My stress levels increased in the earlier days of the pandemic and I began to lose weight,” she says.

“Fortunately, I never stopped taking my HIV treatment due to the insistence of my doctors that I adhere to my treatment regimen,” she says. “I am now determined to show everyone that you can live a full and healthy life as long as you don’t stop taking your medication.”

“The education and support we received from the Hebu Tuyajenge project also greatly helped to alleviate my stress.”

Hebu Tuyajenge is an initiative of the National Council of People Living with HIV, with support from UNAIDS and funded through USAID.

It focuses on increasing the utilization of HIV testing, treatment and family planning services among adolescents and people living with HIV, strengthening the capacity of community organizations and structures and empowering people living with HIV. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic its members educated people living HIV on how to protect themselves from COVID-19.

“In my community, one of the biggest problems was the lack of education and information surrounding COVID-19. Most of us didn’t even know how to properly wash our hands to reduce the risk of catching the virus,” says Ms Damiani.

The Hebu Tuyajenge project is an example of how the government, development partners, civil society and community activists have been key in responding to COVID-19 in the United Republic of Tanzania, providing information, services, social protection and hope to people living with HIV during these unprecedented and trying times.

“The efforts by the government and other donors should continue. Things have now improved in the country because everyone is now aware of the pandemic and people continue to take precautions,” says Ms Damiani.