Feature Story

Championing human rights and health

25 September 2017

25 September 2017 25 September 2017Phylesha Brown-Acton, from the Asia–Pacific Transgender Network, is a champion for the rights of sexual minorities. A volunteer for the Pacific Sexual Diversity Network, she also established F’INE (Family, Identity, Navigate & Equality), which supports Pacific lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people and their families.

“Experiencing discrimination on a daily basis, seeing it happen to my peers and some of my family members because they were related to me, made me think hard about if I wanted to continue living in a society that defines and restricts me or if I was actually going to do something about it. I decided on the latter, and that is why I became a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex rights activist,” Ms Brown-Acton said.

In her work, she has seen the impact that discrimination in health-care settings can have. “I assisted four transgender women in understanding their health needs. All of them told me that they had not been to a doctor for several years, because every time they went to see a health-care provider the experiences were bad. So instead of going to see a doctor when not feeling well, they were medicating themselves at home with over-the-counter medicines. All of those women were later diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Their diagnosis was delayed because of discrimination. The same happens to many people living with HIV.”

Despite the persistent stigma and discrimination that transgender people experience, Ms Brown-Acton believes that discrimination in health-care settings can be overcome. “We need to remove bias in thinking and decision-making,” she said. “We need to work with health institutions and practitioners so that they can hear and understand the discriminatory experiences of transgender people.”

Ms Brown-Acton emphasized the importance of including zero discrimination training in medical school curriculums, pointing out that the Asia–Pacific Transgender Network has developed a Blueprint for Action, a comprehensive, accessible transgender health reference document.

Ms Brown-Acton is adamant that people who experience discrimination—including transgender people, people living with HIV, people with disabilities and indigenous communities—must be at the table when decisions are being made. “Transgender people have been shut out many times before. We have been strategic about getting into the meeting rooms, but there is still a lot of work to be done. We must be heard in those meeting rooms, not silenced or ignored.”

Ms Brown-Actor will be speaking at the Human Rights Council Social Forum, which is being held from 2 to 4 October, about the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of HIV and other communicable diseases. To hear more from her and other human rights activists, register to participate in the Human Rights Council Social Forum at https://reg.unog.ch/event/6958/.

Feature Story

A role without a rulebook—First Ladies discuss development

19 September 2017

19 September 2017 19 September 2017UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé joined the former First Lady of the United States of America, Laura Bush, the First Lady of Namibia, Monica Geingos, and the First Lady of Panama, Lorena Castillo de Varela, on 18 September to discuss how they have used their political platforms and voices to bring attention to some of the most pressing issues affecting the world.

The event, A Role Without a Rulebook: the Influence and Leadership of Global First Ladies, was held at the Concordia Annual Summit in New York, United States, and explored the challenges of being a woman of influence without a job description. Unelected but official, the spouses of government leaders have a unique opportunity to build bridges between civil society and government institutions. The three first ladies each shared how they have navigated the role, crafting their own platforms and agendas for progress.

“I know the power of first ladies,” said Mr Sidibé, who moderated the discussion. “They have become our special champions for ending the transmission of HIV from mother to child. It is when I enlisted their support that we started to see real progress. Now we have some countries that have managed to almost eliminate new infections of HIV among infants.”

Ms Bush discussed her efforts to advance the human rights agenda for women in Afghanistan and her efforts in global health. She recalled her experiences in championing the health of women and girls, including ending the transmission of HIV from mothers to children. Ms Bush focused on her commitment to end AIDS through the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and her desire to build on the positive progress of the AIDS response and eliminate cervical cancer.

“We found out that women were living with HIV, but they were dying from cervical cancer, which is also sexually transmitted through the human papillomavirus (HPV). We launched Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon to add testing and treatment for HPV and the vaccine to the AIDS platform that was already set up with the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. So far, we have been very successful,” Ms Bush said.

Ms Geingos focused on her work with young people and empowerment, emphasizing the importance of young people with regard to issues of gender-based violence, education, health and cultivating entrepreneurship. Ms Geingos said that there is a great need to encourage confidence in young people and to include them in conversations about their health. She spoke candidly about the youth bulge in Africa, where 60% of the population is under the age of 25 years, with the population set to double by 2050.

“We let young people lead the conversation in the language they understand. We use the opportunity to give them important health information. Namibia has done great work with the help of global partners like UNAIDS and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in reducing new HIV infections. We have halved them in less than a decade, and we are about to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV,” said Ms Geingos.

Ms Castillo highlighted her efforts to ensure inclusion and respect for all people. Mr Sidibé noted that Ms Castillo, the UNAIDS Special Ambassador for AIDS in Latin America, has been a powerful advocate for communities and people who are excluded. He highlighted her efforts to counter stigma and discrimination in all its forms in order to build an inclusive society.

“We should all work on leaving no one behind. By leaving no one behind, I mean truly no one,” said Ms Castillo.

From their platforms as global leaders, first ladies are able to take risks, challenge expectations and push against deeply ingrained biases to offer a more inclusive and equitable vision of society.

In closing, Anita McBride, former assistant to former President of the United States George W. Bush and former Chief of Staff to Ms Bush said, “Concordia is an action tank, not a think tank, and this session clearly shows how a first lady’s podium, when used effectively, is a catalyst for action, and for change, and that there is even greater value when they come together and work together.”

Resources

Related

Feature Story

Building the Russian AIDS Centre Foundation for the future

15 September 2017

15 September 2017 15 September 2017The Russian AIDS Center Foundation was founded a year ago by journalist and television presenter Anton Krasovsky to support people living with HIV and share information about the AIDS epidemic.

Today, at the foundation’s office, weekly support groups are held at which people living with HIV and their relatives have access to professional support. Other activities at its office include seminars on legal support, lectures on various aspects of HIV, film premieres and discussions on legislation. A hotline on HIV issues is available for calls from all over the country. Every day, the foundation’s staff address specific requests from people who have been denied treatment, trying to assist everyone who asks for help.

All the work done by the foundation is, one way or another, aimed at responding to stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV in the Russian Federation. “We are fighting discrimination and the fact that people living with HIV are considered “dirty” and contagious. We do this under an umbrella of “Don’t be afraid”—all our work is built around this slogan,” said Mr Krasovsky.

The AIDS Center Foundation exists exclusively thanks to donations by individuals and companies—there are no state or faith-based organizations among the donors. There are only a few members of staff.

“Several people have recently joined our team, who will be responsible for group programmes, lectures and community work. Shortly, a group developing a self-testing programme will join us,” said Mr Krasovsky.

“Independence is important to us. We do not agree with the attitude of government bodies towards people living with HIV, to people who use drugs. We are strong opponents of discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people,” he added.

In recognition of the first anniversary of the foundation, Mr Krasovsky said, “All we achieved is due to our supporters. All my colleagues and myself, all the people who turned to us for help, appreciate and cherish your help. We want you to stay with us in the future, which, despite everything, we still have.”

Related information

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

#Teenergizer2020

13 September 2017

13 September 2017 13 September 2017Adolescents and young people aged between 16 and 19 years from several countries in eastern Europe and central Asia met in Aghveran, Armenia, from 26 to 29 August for the first Teenergizer strategic planning meeting. They discussed the challenges faced by adolescents living with HIV in their countries, shared the results of the #questHIVtest project and developed the #Teenergizer2020 strategic plan.

Teenergizer is a unique movement of 80 adolescents born to mothers living with HIV and HIV-negative volunteers from Georgia, the Russian Federation and Ukraine. They are united by a set of common values, including support for engagement, tolerance and human rights.

The issues addressed in the strategic plan include advocating for adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights, the promotion of age-appropriate information on prevention for adolescents and engaging teenagers living with HIV to raise their voices in the HIV response.

In the #questHIVtest project, teams in Tbilisi in Georgia, Kiev and Poltava in Ukraine and Kazan and Saint Petersburg in the Russian Federation promoted easy, safe and youth-friendly HIV testing among adolescents.

Young people visited HIV testing sites and described the barriers to testing they faced. Using this information, they developed a map showing 63 HIV testing locations, accompanied by personal reviews on the HIV test experience, along with fun places nearby for young people to meet. As a result of the #questHIVtest, 1 925 adolescents from 5 cities have tested for HIV.

Max Saani, from Tbilisi, said, “It’s extremely helpful for teenagers to have a map on which adolescents can find youth-friendly testing locations and receive proper help and support.” “This map is very unusual, with fun teen places not even seen in Google Maps,” added Yana Valchuk, from Kiev.

Among the challenges and barriers faced by adolescents during the #questHIVtest were a lack of HIV information, stigma around HIV testing and talking about HIV with friends, the high cost of HIV tests and parental consent. The lack of anonymous HIV tests for young people and the shortage of trained doctors, social workers and psychologists to support adolescents living with HIV were also barriers.

Timur Khayarov, from Kazan, explained that the reasons why many adolescents in the Russian Federation are afraid to take an HIV test include the age limit—14 to take the test with parental consent, 16 without parental consent—and because the test results of minors must be communicated to their parents. “When I was refused an anonymous HIV test because of my age, I showed the personnel a printout of the law. The #questHIVtest helped me to defend my right to services,” he said.

The #questHIVtest project was undertaken with support from UNAIDS and the Viiv Healthcare Foundation.

“I’m convinced that the future is in the hands of adolescents—they are the people who will change and build a new world. By 2020, Teenergizer will be a few steps closer to the world that it seeks,” said Armen Agadjanov, an HIV activist from Yerevan, Armenia.

Related information

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

China’s community health services are a model for the world

21 August 2017

21 August 2017 21 August 2017The Yuetan Community Health Centre is nestled on a narrow lane in an old residential part of central Beijing, China. Its yard is packed with bicycles, rather than cars—an indication that the centre is serving people close to where they live.

“Through our centre and nine affiliated community health stations, we provide services to 150 000 people living in the Yuetan area,” said Du Xue Ping, Director of Yuetan Community Health Centre. “In addition to providing medicine, we also undertake health promotion, encouraging people to lead a healthy life. We know that prevention is far better than cure.”

The centre blends state-of-the-art Chinese medicine and Western medicine, serving 420 000 patients annually. It supports the community’s rapidly ageing population, overseeing two senior homes and staff who conduct home visits for seniors and people with mobility problems.

The facility is part of China’s highly regarded multitiered medical system, which has successfully brought life-saving services to people across the country. In this system, major diseases are handled in large hospitals and routine services are treated in community health centres. According to Chinese data, in 2015 there were more than 34 000 similar community health clinics providing essential health services to 706 million people in China. “Community health centres are the first line of defence in protecting people’s health,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “The family-centred interface and clear bond between staff and patients exemplifies people-to-people connections.”

Mr Sidibé visited the community health centre to learn more about its holistic and comprehensive approach and how China’s community health system could help to inform the 2 million community health workers initiative, which was recently endorsed by the African Union.

In the 1970s, China’s community-based doctors dramatically improved access to health care in rural communities and were an inspiration to many other countries. China exported the model, sending teams of doctors and nurses to Africa.

“I know from my own personal experience the contributions China has made to primary health care in Africa,” said Mr Sidibé. “Chinese doctors provided crucial medical services to people in Mali where I am from.”

“The world can learn a lot from the Chinese experience,” said Mr Sidibé. “I am very impressed by the professionalism I witnessed here today.”

Region/country

Feature Story

Young people - continuing the conversation on HIV

11 August 2017

11 August 2017 11 August 2017Although new HIV infections and AIDS deaths among young people have decreased, in many places knowledge about how to prevent HIV remains worryingly low. Ahead of International Youth Day UNAIDS spoke to four young people about the challenges they face around HIV.

Pavel Gunaev is 16 years old and lives in St. Petersburg, where he is part of the youth-led network of adolescents and young people living with HIV Teenergizer! Pavel said that in his city young people are not aware about HIV.

“AIDS isn't talked about so young people don’t know about the risks or how to protect themselves from HIV,” he said. “As a result, so many uninformed young people are acting and making decisions based on rumors.” Pavel believes that if everyone does more to inform adolescents and young people and dispel the myths around HIV, ending AIDS will be possible.

Chinmay Modi was born with HIV twenty-three years ago. He is a member of the National Coalition of People Living with HIV in India and country focal point for the Youth LEAD Asia Pacific Network.

“The biggest problem is raising awareness and giving young people age-appropriate information,” he said. In his view, parents are not comfortable talking with their children about sex and society shies away from it too. As a result, he explained, young people are engaging in sex and experimenting new things but with little knowledge of the risks involved.

“Condoms need to be promoted and partners should support youth empowerment so that everyone is held accountable,” Chinmay said. He is also frustrated because in India people cannot access stigma-free HIV services at an early age.

In his view, self-stigma is hampering efforts to tackle discrimination, violence and inequalities related to HIV. That’s why, he explained, he wants more people to share their stories and be positive about being positive.

Moises Maciel couldn’t agree more with Chinmay. He is a 20-year-old LGBT and HIV activist. He became a member of the National Network of Adolescents and Youth Living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil after discovering his positive HIV status two years ago. Since then, he has been on a journey against HIV-related stigma. He has also been motivating his peers to get tested.

“Young people are still at great risk of HIV infection due to a variety of factors such as social marginalization related to gender and racial inequalities,” he said. “In Brazil, young transgender and gay people are particularly targeted,” he explained.

He said that it baffles him to see how stigma and prejudice still dominate despite people living with HIV living healthy lives with the help of antiretroviral therapy. “We should start talking to young people in an open and responsible way about sexuality, sexually transmitted infections, teenage pregnancy and life responsibilities,” Moises said.

Lorraine Anyango, a Boston-based youth health and rights advocate, works to ensure that young people's voices, specifically around HIV, get heard.

“Young people continue to be left out of spaces and discussions on issues that impact their lives,” Lorraine said. “Their autonomy as individual human beings continues to go unacknowledged, leaving them susceptible to the risk of HIV infection.”

In her opinion, young people’s participation in decisions that affect their health can contribute to strengthen national-level accountability, by ensuring that programmes are effectively responding to their needs. Lorraine concluded by saying, “Recognizing youth sexual and reproductive health and rights, and continuing the conversation on HIV will get us closer to ending AIDS by 2030.”

Feature Story

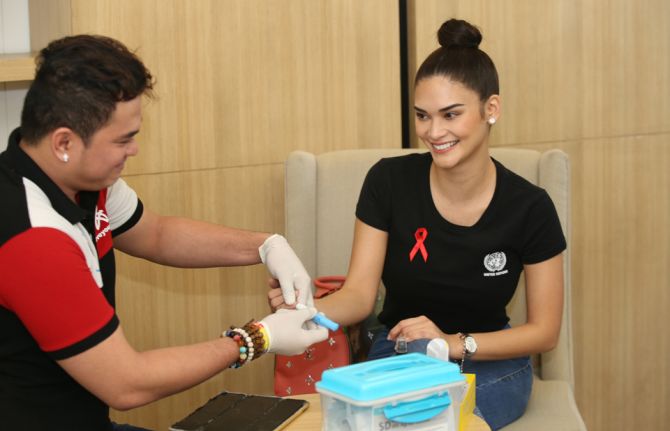

UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach ramps up HIV advocacy efforts

09 August 2017

09 August 2017 09 August 2017Miss Universe 2015 and UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Asia and the Pacific, Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach has launched an HIV awareness campaign with a public HIV screening. On 9 August, the model and actress, along with Mayor Lani Cayetano of Taguig City in the Philippines undertook the screening which was conducted by the community organization LoveYourself in Taguig City.

“As the UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Asia and the Pacific, I wanted to start my HIV advocacy here at home in the Philippines,” said Ms Wurtzbach. “It’s important because the country has the fastest growing HIV epidemic in the region.”

A recent UNAIDS report has found that new HIV infections in the Philippines increased 140% between 2010 and 2016. Taguig City is one of the 17 cities in the Metro Manila area, which account for 40% of new infections in the country. Mayor Cayetano is the national chairperson of the League of Cities in the Philippines and promised to encourage other cities to scale-up HIV testing.

“The city of Taguig will always be here to support you Pia,” said Mayor Cayetano.

Ms Wurtzbach unveiled the project Progressive Information Awareness campaign, or the PIA project which aims to inform young people about HIV through social media, youth-friendly and informative videos, as well as promote policies which will enable young people, particularly from key populations to access HIV and other key health services. The PIA project is also working with a coalition of government, non-profit organizations and business partners on a major fundraising and award World AIDS Day Gala.

“With the PIA Project we hope to see an increase in HIV awareness, spread love for people living with HIV, and make HIV testing among Filipinos a normal part of their health and wellness routine,” said Ms Wurtzbach.

Across Asia and the Pacific young people from key populations are at higher risk of HIV.

“The HIV movement among young people that Pia is lighting up here in the Philippines will resonate around the Asia-Pacific region,” said Eamonn Murphy, Director, UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia-Pacific.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Turning his life around with harm reduction in Belarus

18 July 2017

18 July 2017 18 July 2017The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development takes to scale what the AIDS response has been working towards for 30 years—a multisectoral, rights-based, people-centred approach that addresses the determinants of health and well-being. The individual stories in this series highlight the linkages between HIV and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each told from the personal perspective of people affected by HIV. The series paints a picture of how interconnected HIV is with the SDGs and how interdependent the SDGs are with each other. Most importantly, the stories show us the progress we have achieved with the AIDS response and how far we have left to go with the SDGs.

After nearly 15 years of injecting drugs, Sergey gave up hope. He had tried a number of times to kick his addiction, but he had failed miserably.

In 2009, in a last ditch effort, he enrolled in the Belarus Opioid Substitution Therapy Programme.

“My relatives did not believe this programme would help me and thought of it as just another hopeless attempt to quit drug use,” Sergey said.

His biggest challenge, he explained, was to prove to doctors and his relatives that he really wanted to stop injecting drugs and that this would help him cope with his drug addiction.

He comes every day to the government opioid substitution therapy (OST) centre in Minsk to receive a medical dose of methadone, which helps to alleviate his dependence on opioids.

A friend who lived in Germany told him about harm reduction and substitution therapy, but he never believed that one day it would be available in Belarus.

Sergey is one of nearly 900 people enrolled in the OST programme, which started in 2007 with a grant from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. It includes the provision of methadone under strict medical supervision, regular medical check-ups, psychological support and social work services. In addition, OST helps people living with HIV who used to inject drugs to maintain adherence to their daily regimen of antiretroviral therapy.

Today there are 19 government OST sites across Belarus, but these still cover less than 5% of people who inject drugs in the country. Belarus wants to increase coverage to at least 40% of people who inject drugs in order to lower the number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs.

In Sergey’s case, the programme helped him turn his life around. Not only did he get a job and keep it, but he suddenly had plans for himself.

SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

Good health is a prerequisite for progress on ending AIDS. Ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages, including people living with or at risk of HIV, is essential to sustainable development. For example, successfully ending the AIDS epidemic will require enormous health service scale-up, with a focus on community services, targeted testing strategies, ensuring treatment is offered to people following diagnosis (including regimes appropriate for babies, children and adolescents), and regularly support and monitoring for people on antiretroviral medicines. Eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV depends on providing immediate treatment to pregnant women living with HIV, integrating HIV and sexual and reproductive health services, and engaging male partners in prevention and treatment services.

Increasing service integration in a way that responds to individuals’ needs—whether that be combining tuberculosis (TB) and HIV services or providing youth-friendly HIV, sexual and reproductive health services—leads the way in reshaping efficient, accessible and equitable health services for HIV and beyond. HIV can be ended only by promoting the right of all people to access high-quality HIV and health services without discrimination.

The following stories explore how inextricably linked SDG 3—ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages—and ending AIDS are. For every individual, protecting and maintaining good health underpins the capacity to fulfil their multiple roles within family, community, society and the economy. Mona’s story recounts her struggles with HIV and TB, discrimination, and the right to be treated fairly and with dignity. Lidia works with partners in the health services, community health system and private sector to ensure female seasonal coffee pickers are given the information and services they need to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Sergey describes his experience of how a harm reduction programme helped him overcome his addiction while adhering to antiretroviral therapy. Christine tells her story of how, as a community health worker, she reaches out to women where and when they need her to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

Learn more about SDG Goal 3

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Mona’s dream: a world free of stigma

12 July 2017

12 July 2017 12 July 2017The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development takes to scale what the AIDS response has been working towards for 30 years—a multisectoral, rights-based, people-centred approach that addresses the determinants of health and well-being. The individual stories in this series highlight the linkages between HIV and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each told from the personal perspective of people affected by HIV. The series paints a picture of how interconnected HIV is with the SDGs and how interdependent the SDGs are with each other. Most importantly, the stories show us the progress we have achieved with the AIDS response and how far we have left to go with the SDGs.

When friends and family stopped coming to Mona Balani’s house, she was stoic. But worse was to come when no one would play with her six-year-old.

“My elder son had to face so much discrimination at that time,” Mona recalled, when she and her husband tested positive for HIV in 1999. “Relatives would say nasty things to him: ‘Your parents will die one day, and you will die too’.”

Holding back tears, she remembered that every time she came home in the evening, her son would hug her and ask her not to leave him alone. Mona’s husband had been sick off and on for three years. He was eventually diagnosed with TB. Because of the couple’s HIV status, sometimes medical staff would refuse to admit him to the hospital.

“More than once, doctors, nurses or lab technicians made objectionable sexual remarks,” Mona said. Because of how people responded to them, they often felt like they had committed a crime.

Meanwhile her youngest son became sick and was later diagnosed with TB. Mona explained that the mounting costs of medicines for her husband and her two-year-old meant she could not afford HIV treatment for herself as well.

Sadly, her youngest son died a month later. “I knew I had to overcome everything and move forward and live for my older son,” she said.

In 2002 Mona found out that she too had TB of the lungs. She began and completed treatment within the stipulated six-month period. Three years later, Mona’s husband’s condition worsened. He passed away in 2005. Her ordeal did not end there. The following year she developed abdominal TB.

“When I was getting tested for TB I had to be admitted to the hospital for a night to get my diagnosis done, but after looking at my HIV status the staff declined to take me in,” Mona said. She called a retired doctor she knew, who contacted a colleague of his so that she could stay.

“Even after admitting me, the doctor who examined me asked me to replace all the equipment used and the bedsheet from the bed. The doctor would always wear double gloves before examining me,” recalls Mona.

By then, Mona had been on antiretroviral therapy and she started her TB treatment. She also decided she could help fight stigma surrounding TB and HIV.

In 2007 she began working with the Network for People Living with HIV/AIDS in remote areas of Rajasthan. Ten years later she lives in New Delhi and works for the India HIV/AIDS Alliance. She dreams of a world where people affected by HIV and TB have rights and are respected and can lead normal lives, ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all at all ages.

“People think that HIV only leads to death, but that is not true,” Mona said. “I proved to the world that you can live a healthy life with HIV, and I am still leading a healthy life.”

SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

Good health is a prerequisite for progress on ending AIDS. Ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages, including people living with or at risk of HIV, is essential to sustainable development. For example, successfully ending the AIDS epidemic will require enormous health service scale-up, with a focus on community services, targeted testing strategies, ensuring treatment is offered to people following diagnosis (including regimes appropriate for babies, children and adolescents), and regularly support and monitoring for people on antiretroviral medicines. Eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV depends on providing immediate treatment to pregnant women living with HIV, integrating HIV and sexual and reproductive health services, and engaging male partners in prevention and treatment services.

Increasing service integration in a way that responds to individuals’ needs—whether that be combining tuberculosis (TB) and HIV services or providing youth-friendly HIV, sexual and reproductive health services—leads the way in reshaping efficient, accessible and equitable health services for HIV and beyond. HIV can be ended only by promoting the right of all people to access high-quality HIV and health services without discrimination.

The following stories explore how inextricably linked SDG 3—ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages—and ending AIDS are. For every individual, protecting and maintaining good health underpins the capacity to fulfil their multiple roles within family, community, society and the economy. Mona’s story recounts her struggles with HIV and TB, discrimination, and the right to be treated fairly and with dignity. Lidia works with partners in the health services, community health system and private sector to ensure female seasonal coffee pickers are given the information and services they need to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Sergey describes his experience of how a harm reduction programme helped him overcome his addiction while adhering to antiretroviral therapy. Christine tells her story of how, as a community health worker, she reaches out to women where and when they need her to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

Learn more about SDG Goal 3

Feature Story

Quezon City’s HIV programme becomes a model for other cities

13 July 2017

13 July 2017 13 July 2017The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development takes to scale what the AIDS response has been working towards for 30 years—a multisectoral, rights-based, people-centred approach that addresses the determinants of health and well-being. The individual stories in this series highlight the linkages between HIV and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each told from the personal perspective of people affected by HIV. The series paints a picture of how interconnected HIV is with the SDGs and how interdependent the SDGs are with each other. Most importantly, the stories show us the progress we have achieved with the AIDS response and how far we have left to go with the SDGs.

Klinika Bernardo, popularly known as the Sundown Clinic, is located along a bustling highway. It operates from 15:00 until 23:00, allowing a maximum number of clients to visit. “We cater to men who have sex with men from all over the Philippines,” said Leonel John Ruiz, head physician at Klinika Bernardo. “Only 40% of our clients are from Quezon City.”

In 2012, Quezon City became the first city in the Philippines to open a clinic providing services for men who have sex with men and transgender people. From the start, demand for services at the Sundown Clinic was high. Almost 250 HIV tests and pre- and post-test counselling services were carried out in its first two months of operation, and 18 people tested positive for HIV.

Although same-sex relationships are legal in the Philippines, there is a high degree of stigma and discrimination towards men who have sex with men. Fear of being outed and ostracized prevents many men from accessing traditional health services. Studies by city health officials show that two-thirds of men who have sex with men in Quezon City have never had an HIV test.

“This is my first HIV test. I do not know what to expect,” said one young man while filling out registration forms. “I tried to read up on HIV so I would have some background information, but it took me a while to gather the courage to come here.” The young man found the staff supportive and skilled at calming his nerves. People who test positive for HIV receive counselling on antiretroviral medicines and are accompanied by staff through their initial months of HIV treatment, which is free in the Philippines.

Quezon City now operates three Sundown Clinics and in the past few years has significantly increased investments in its HIV programmes. With nearly 3 million residents, Quezon City is the Philippines’ most populous urban centre and has made stopping a burgeoning AIDS epidemic a top priority. Mayor Herbert Bautista has encouraged city residents to know their HIV status, and he has taken an HIV test in public. The city’s effort to scale up HIV testing among men who have sex with men has proven successful, with such tests increasing 30 times. Forty per cent of the city’s HIV tests take place in Sundown Clinics, effectively proving that removing barriers increases access to services.

“Since we have been operating, the perspective has definitely changed,” says Leonel. “Before, we would have a hard time inviting people for testing. Now, most of our clients are walk-ins. People are personally and actively seeking information.” Several other local city governments are starting to adapt the Quezon City model and establish their own clinics.

The Sundown Clinic staff speak proudly of their achievements, but they look forward to closing shop one day. “I pray before sleeping,” says Adel, the only female peer educator at Klinika Bernardo. “I hope that one day there will be no one in need of our services. That’s what I am working for.”

SDG 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development

Early in the AIDS response, in the absence of treatment options and the overwhelming scale of people affected by HIV, it was clear that a purely clinical response to the epidemic was not sufficient. Relatives, faith-based organizations and alliances of people affected by HIV stepped in to do what they could to help people die with dignity, to support the orphans, spouses and dependants left behind and to fight for a new way of doing things. Groups of vastly different people linked by the shared experience of the fear and stigma and horror of HIV and AIDS came together to demand that the response go beyond clinics, hospitals and the formal health service.

Embracing and expanding the concept of partnership was revolutionary, not for AIDS but also in the broader development sphere. Partnerships continue to be central to the AIDS response. Coordination and collaboration across a wide range of partners, including sex workers, scientists and social workers, helps to identify and use expertise more effectively, overcome barriers more quickly and allocate resources more efficiently. Partnerships increase awareness and knowledge and create a critical mass of power and support that help to influence policy-makers and spur stakeholders to take action.

The story of the Sundown Clinic in Quezon City in the Philippines embodies SDG 17—strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development. The success of the original clinic and the subsequent addition of two more clinics demonstrate how inclusivity continues to define the AIDS response and provide the inspiration for successful partnerships between a wide diversity of stakeholders.