Feature Story

Universal access to top-of-the-line medication in Brazil

14 July 2017

14 July 2017 14 July 2017The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development takes to scale what the AIDS response has been working towards for 30 years—a multisectoral, rights-based, people-centred approach that addresses the determinants of health and well-being. The individual stories in this series highlight the linkages between HIV and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each told from the personal perspective of people affected by HIV. The series paints a picture of how interconnected HIV is with the SDGs and how interdependent the SDGs are with each other. Most importantly, the stories show us the progress we have achieved with the AIDS response and how far we have left to go with the SDGs.

New Year celebrations took a turn for the worse last year for Welber Moreira. The 23-year-old Brazilian found out he was living with HIV.

He described feeling ill the day after Christmas, so he went to a public health clinic to get some answers. Instead, the doctor posed a startling question. He asked me, “‘Can I see your most recent HIV test result?’” Welber had never thought that a virus from some long-gone biology class would ever affect him. The doctor told him to go to one of the public voluntary counselling and testing centres in his hometown of Ribeirão Preto, north of São Paulo, where he took a rapid HIV test. His positive diagnosis was confirmed by a second test.

“After all the crying in front of the nurse, I thought of my girlfriend, because we had not been using condoms,” Welber said. His girlfriend tested negative for HIV. She began her 28-day prevention treatment even before Welber started taking his own antiretroviral medicine. Brazil’s public health system covers all HIV prevention and treatment costs, which made it easy for both of them to start taking medicines.

Something else worried him. “I was very scared and afraid of the side-effects,” Welber said. Surprisingly, he said, he has felt fine since starting his HIV treatment. Now, before going to bed he takes two pills a night. Shrugging his shoulders, he said, “I can’t imagine what it was like in the past, to take several pills a day, at different times.”

He is among more than 100 000 Brazilians to be given a new HIV medicine called dolutegravir (DTG), which has fewer side-effects and is more effective. The Brazilian Ministry of Health successfully negotiated to purchase DTG at a discount of 70%, bringing down the price per pill to US$ 1.50 from US$ 5.10. As a result, more people will have access to this new medicine within the approved budget for treatment in the country (which stands at US$ 1.1 billion for 2017).

Welber is thankful for his girlfriend’s support and the efficiency of the clinic and centre, all of which helped him overcome the initial trauma.

Bringing up HIV and his status no longer upsets Welber. He said he speaks openly about it to his friends and at work. A small part of his family didn’t cope well with the news but he has not lost hope.

He has big plans with his girlfriend. “We plan to have two kids, starting three years from now,” he said.

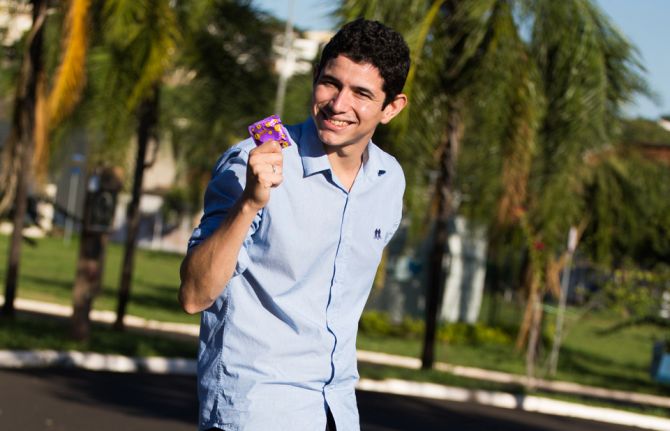

He also said that he feels like he has to help others. “Whenever I can, for example, I pass by the local health clinic and grab some condoms for my colleagues at work and my friends,” Welber said. “It’s an opportunity for me to share what I know and to talk about prevention.”

SDG 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

The scale-up of HIV treatment in low- and middle-income countries over the past 15–20 years is one of the greatest success stories of global health. In sub-Saharan Africa at the end of 2002, only 52 000 people were on treatment. Thanks to increased levels of production and full use of patent flexibilities, the number of people on treatment grew to 12.1 million in 2016. Lessons learned from the AIDS response have gone on to increase access to medicines for people living with TB, hepatitis C and noncommunicable diseases.

Researchers and scientists continue to innovate and improve the efficacy of antiretroviral medicines and to pursue a cure for HIV. Antiretroviral medicines have evolved so a person living with HIV who is taking their medicines regularly can now expect to live a normal lifespan.

When the Brazilian Government granted universal access to antiretroviral medicines in 1996 they changed the course of the national epidemic and increased survival rates remarkably. Dire predictions of large-scale AIDS-related deaths never came to pass. Brazil’s Unified Health System is continuing to lead the way and has recently incorporated the most advanced scientific and medical technology into routine HIV services. Welber’s story tells us how much SDG 9—build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation—is interwoven with increasing equitable access to medicines and achieving progress on ending AIDS.

Learn more about SDG Goal 9

Region/country

Related

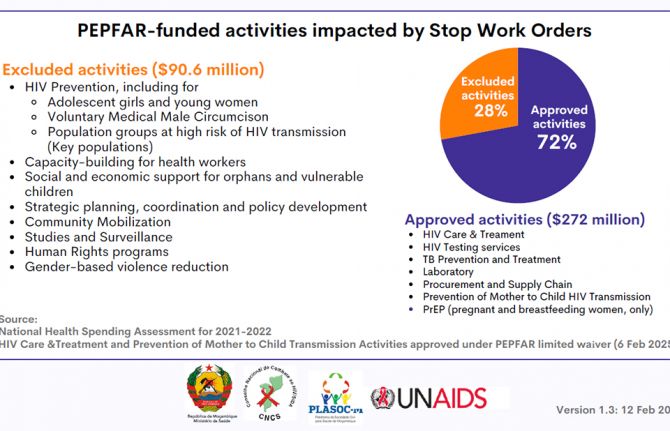

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

22 December 2025

Feature Story

Speaking openly about sex and HIV

17 July 2017

17 July 2017 17 July 2017The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development takes to scale what the AIDS response has been working towards for 30 years—a multisectoral, rights-based, people-centred approach that addresses the determinants of health and well-being. The individual stories in this series highlight the linkages between HIV and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each told from the personal perspective of people affected by HIV. The series paints a picture of how interconnected HIV is with the SDGs and how interdependent the SDGs are with each other. Most importantly, the stories show us the progress we have achieved with the AIDS response and how far we have left to go with the SDGs.

Eighteen years ago, at the age of 19, Florence Anam became pregnant. As a teenager she had been flattered by an older man showering her with attention. A good student in school and just about to start university, her parents told her that they were disappointed in her, but never brought up the subject again.

“When I was pregnant, there were never any questions of how I got in this situation or who was responsible,” Florence said. “Sex was a taboo topic and not a discussion that parents had with their children.”

Florence did not know of her HIV status until 2006. During a national Kenyan HIV prevention campaign, she and four other friends went to get tested. When the HIV tests confirmed she was living with HIV, she was shocked.

The reality hit when a year later Florence was dismissed from her job because of her HIV status. “Back then, there were no HIV networks for young people, neither was there as much information available, so I contacted a woman who had been featured in a newspaper and lashed out at her, asking, “Why am I not allowed to be productive if I am not sick yet?”” explains Florence.

That woman, Asunta Wagura, was the Director of the Kenya Network of Women with AIDS. Asunta asked Florence to come in and see the organization, for which she then started volunteering. She describes the experience as a serious reality check. She heard other women’s stories, of how many of them lived in poverty and dealt with violence. “It was like plunging into this world that as a protected child I never even knew existed; all of a sudden my problems became trivial and I knew I needed to let other people know what I was seeing every day.”

She also became more vocal about HIV, bringing a lot of attention to herself and her status.

“I was done with having people dictate to me what their opinions about my life were, I missed the girl that I was and I desperately needed to get out that hole,” she says.

Part of Florence’s advocacy and communications work with the International Community of Women Living with HIV involves monthly mentoring meetings with girls and young women living with HIV. “I want to raise their consciousness regarding their life 20 years down the road,” Ms Anam says.

Florence considers that her life is full. Her 17-year-old son and 11-year-old adopted daughter affectionately chide her for bringing up sex and other “awkward” subjects at the dinner table.

“I am like the weird mother speaking about sex and responsible sexual behaviour in the most insane places,” Ms Anam says. “I keep repeating to them that decisions you make now, however immature, will have a long-term impact.”

SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Gender inequality, discrimination and harmful practices create a culture that negatively impact women, girls, men and boys. Girls and women are disproportionately vulnerable to and impacted by HIV infection. Frequently they do not have the ability to control or determine their own life choices, such as going to school, who they marry or have sex with, the number of children they have, the health-care services they access, their employment options, or their ability to voice an opinion and be respected.

Programmes designed to educate and inform girls and women about the risks of HIV and provide some means of protecting themselves are essential building blocks of the AIDS response. And yet, however necessary, they are insufficient. Access to comprehensive sexuality education and sexual and reproductive health services can only ever be partially successful in protecting girls and young women from HIV if their potential male partners remain unaware of or unwilling to change their behaviour. Increasing male awareness of the risks of HIV, providing men and boys with the means of prevention, and enabling them to change their own behaviour and see the benefits of a balanced and respectful relationship are essential to decreasing the number of new HIV infections and increasing gender equity.

Like many young women, Florence grew up without comprehensive sexuality education or access to sexual and reproductive health services. She has made it her life’s work to expand youth-friendly HIV and health services and to mentor young women living with HIV, giving them hope for the future. Florence’s story encapsulates how important progress on SDG 5—achieve gender equality and empower all girls and women—is to enabling young women and men to make informed decisions on protecting themselves from HIV infection.

Learn more about SDG 5

Region/country

Related

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

22 December 2025

Feature Story

Community health worker leads the way in Burkina Faso

19 July 2017

19 July 2017 19 July 2017As a young volunteer in a Burkina Faso hospital, Christine Kafando, had a lot of convincing to do. In 1997, HIV meant deadly illness so no one believed her when she told people living with HIV that she was positive.

“People accused me of lying saying I was too healthy looking,” she said. One time, Ms Kafando took her treatment with someone to show them that she was indeed living with HIV.

Despite patients’ resistance, she persevered. She even started going to people’s homes to do routine check-ups.

“At the time,” she explained, “the hospitals and staff did not know how to handle HIV, so we stepped in and filled the gap.”

It had been a year since Ms Kafando had found out that she was living with HIV. She and her university sweetheart (and now husband) had gone for a test together. He was negative but she was not.

She describes being very scared and her dreams dashed. Her husband desperately wanted children and left her six months after her diagnosis. With her family’s support, she started raising awareness about HIV. Ms Kafando became the first HIV positive woman to reveal her status publicly in Burkina Faso.

“I realized that people thought HIV happened to others but I proved to them that it can happen to anyone,” she said.

Having joined the newly formed REVS+ organization - run and led by people living with HIV- as a volunteer, she found her purpose.

She became as trusted as the various doctors and often acted as a liaison between families and the hospital.

It dawned on her that helping people access treatment and monitor their health was one thing but more needed to be done on the prevention front.

She split her time between the hospital and testing clinics.

Tirelessly Ms Kafando hammered over and over the same message, “Better to know what ails you than live in ignorance. Get tested.”

The ‘loudmouth’ as her peers call her even got Burkina Faso’s president to pay attention. “I told him, ‘if you do nothing about HIV, you will have no one left to govern,’” she said proudly.

Suddenly she knew that her fighting spirit paid off because the then president Blaise Compaoré not only got tested but treatment costs decreased and testing became free of charge for women and children.

Burkina Faso sociologist and HIV technical coordinator Dao Mamadou describes Christine as someone who puts words into actions.

“She has dedicated nearly 20 years of her life helping women and children living with HIV who has never ceased to serve others,” Mr Mamadou said.

She adopted two children and furthered her experience in the health sector.

Reflecting back to 2003, she said that as community healthworkers, they had forgotten a key component.

“A few times, couples living with HIV would come to see me and I would inquire about their baby and the mom would say, ‘he died,’” she said.

No one had thought about HIV transmission to babies and the children’s well-being beyond birth so Ms Kafando founded the Association Espoir pour Demain (AED).

Her organization raised HIV awareness among expectant mothers and in maternity wards. In no time, AED became the reference for all pregnant women living with HIV.

Mr Mamadou, the HIV technical coordinator, said he had seen Christine become an icon.

“She is considered to be our Mother Teresa for countless orphans and vulnerable children,” he said.

Through time her organization branched out beyond Bobo Dioulasso. She got various HIV organizations to join together to coordinate funding and resources better.

Her proudest moment, she said, was getting French and Burkina Faso national recognition in 2011.

“I realized upon getting those honors that I saved lives,” she said.

Her current schedule has her shuffle back and forth from the capital city to Bobo almost twice a week.

She is frustrated because young people these days seem impermeable to HIV.

“HIV treatment has coaxed people into thinking that they can beat this, but that’s not the way to think about it,” she said.

Her current battle entails launching new HIV prevention campaigns and getting the word out although she admitted, “I will always be a fighter in the AIDS response.”

Region/country

Feature Story

In conversation with Toumani and Sidiki Diabaté

19 July 2017

19 July 2017 19 July 2017Just an hour before they were expected on stage at the Montreux Jazz Festival, two-time Grammy award winning kora player and UNAIDS International Goodwill Ambassador, Toumani Diabaté and his talented son Sidiki sat down to talk music, diversity, zero discrimination and ending AIDS in West and Central Africa.

Gentle and thoughtful, Toumani answered the questions with warmth and good humour, and in true global fashion the conversation flowed between English, French and Bambara. There is clearly a lot of respect between father and son as traditions are passed down and innovation encouraged. Their banter was light-hearted as Toumani advised Sidiki to sit up straighter and look into the camera while Sidiki offered more modern takes to his father’s answers.

UNAIDS: You are here to perform with Lamomali, a musical collaboration with French artist Matthieu Chedid. You have more than 15 people with you on stage including the likes of Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara. How did this come together?

Toumani: Part of the griot tradition of historians, storytellers and musicians, I have always wanted to be involved. My fathers, all my family from a 700-year-old dynasty, we come from this atmosphere, we are born into this and we are the archive of culture in our country.

Beautiful music brings people together and breaks down barriers like in Lamomali. The world needs to be more open and be more helpful and we need more communication. That is the only way that things can be better in the future.

UNAIDS: Recently the African Union endorsed a catch up plan for West and Central Africa to accelerate access to HIV services. What are your hopes for the region?

Toumani: Clearly, we cannot accept a two-speed approach to ending AIDS in Africa. We don’t have a moment to lose, we have the tools and must work together to end AIDS.

UNAIDS: Tonight, you are going to wear a red ribbon during the concert. What does it mean to you?

Toumani: Life, it is just life, love and solidarity.

During the high-energy performance, which celebrated both the traditional and the new—Toumani spoke about his role as UNAIDS International Goodwill Ambassador and highlighted the importance of zero discrimination. He shared a proverb from his native Mali:

If you know you do not know, you’ll know.

If you do not know you do not know, you’ll never know.

If you do know, make it known.

This speaks to Toumani’s role both as griot and Ambassador. He knows the importance of celebrating diversity and dignity and making zero discrimination a reality for all. Through his vibrant music and his messages, he is making it known.

Feature Story

New campaign launched to raise awareness about maternal health

07 August 2017

07 August 2017 07 August 2017Mediaplanet has today launched a new campaign to raise awareness about maternal health around the world.

Created in partnership with UNAIDS and other international organisations, the campaign looks at a range of case studies on issues affecting pregnant women and mothers, and draws on insights from community health-care providers, as well as public health advocates.

Participating in the campaign, UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé said: “We need to reinforce the interface between health service providers and the community to better monitor what is going on in each community. That way we can quickly make sure that pregnant women have access to health services and monitor them not only for HIV, but for all health issues.”

According to UNAIDS’ latest report, Ending AIDS: progress towards the 90-90-90 targets, around 76% of pregnant women living with HIV had access to antiretroviral medicines in 2016, up from 47% in 2010. In addition, five high burden countries—Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland and Uganda—have met the milestone of diagnosing and providing lifelong antiretroviral therapy to 95% of pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV. Nonetheless, AIDS-related illnesses remain the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) globally.

“People have to be courageous and speak up for sexual education and highlight just how critical it is,” said Mr Sidibé. “We have to make sure that girls have access to information early and give them the skills to help them deal with their sexuality in a more empowered manner.”

UNAIDS is working with a broad range of partners, including governments, civil society, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, to ensure that women and girls everywhere are empowered and enabled to protect themselves against HIV and that all women and girls living with HIV have immediate access to treatment.

The campaign is available online and will be distributed as a printed supplement in today’s edition of the Guardian.

Feature Story

UNAIDS Executive Director addresses Parliamentary Assembly of the Francophonie

11 July 2017

11 July 2017 11 July 2017The UNAIDS Executive Director, Michel Sidibé, has addressed the 43rd Session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Francophonie on the centrality of the Francophonie in making progress towards the end of AIDS.

The assembly, which brings Francophone parliamentarians together annually to exchange views, learn about good practices and take a position on cross-cutting issues affecting the French-speaking world, met on 10 July in Luxembourg.

Nearly 600 members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Francophonie and more than 20 presidents of parliamentary assemblies gathered for the event, which was held under the theme of “Linguistic diversity, cultural diversity, identities”.

Quotes

“The Francophonie, more than a linguistic tool, constitutes a political and scientific space, built around common values.”

“It seems to me to be essential to insist on the cultural dimension governing human relations, both within a single society and in relations between peoples.”

“I welcome the allocation of 1% of the Grand Duchy’s budget for development cooperation. Diversity is to be cherished, preserved and promoted.”

“We, the Francophonie, constitute so many actors of massive movement for peace and stability, for the eradication of discrimination and violence against women, for full respect for their rights and economic empowerment, for access to quality education and training for all, to create decent and sustainable jobs, especially for young people, for shared growth, for sustainable and responsible development and for the full development of linguistic and cultural diversity.”

“Our identity is based on the francophone values we are committed to defend.”

Region/country

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025

Feature Story

Accurate and credible UNAIDS data on the HIV epidemic: the cornerstone of the AIDS response

10 July 2017

10 July 2017 10 July 2017Once a year, UNAIDS releases its estimates on the state of the worldwide HIV epidemic. Since the data can literally affect life and death decisions on access to services for treatment and prevention—and are used to decide how to spend billions of dollars a year—they need to be as accurate as possible and be regarded as credible by everyone who uses the information.

How we collect and interpret HIV data has huge consequences—a pregnant woman visiting an antenatal clinic can help calculate the size of the country’s HIV epidemic, can help shape national policies for the response to HIV and can influence the size of grants to respond to HIV from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and others.

So, how do we do it?

Collecting data on the ground

We don’t count people. We can’t—many people who are living with HIV don’t know that they are, so can’t be counted. And everyone in a country can’t be tested every year to calculate the number of people living with HIV. Instead, we make estimates.

The data that are published in our reports, quoted in speeches and used by governments around the world to plan and implement their AIDS responses originate on the ground, in a clinic, in a hospital or anywhere else that people living with HIV access, or need, HIV services.

Take the example of a pregnant women visiting an antenatal clinic as part of her routine antenatal care. She will be offered an HIV test, which will show her to be either HIV-positive or HIV-negative. An HIV-positive result will, of course, open up for the individual mother the range of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services available to keep her well and her baby HIV-free, but the result, whether negative or positive, will also be used to determine the wider impact of services and the success of country programmes.

Some countries operate a so-called sentinel survey system, in which a network of reporting sites collect data. If the clinic is one of these, a sample of blood will be anonymized and collected with results from the other sentinel sites, resulting in a large set of data to estimate trends from the sentinel sites over time.

In other countries, data from all women who are being tested routinely at all antenatal care sites are used to estimate HIV prevalence. Her test result will be recorded and passed on to the country’s national-level HIV reporting agency.

Data from antenatal clinics, when combined with information from broader, but less frequently collected, population-based surveys, are the basis for HIV data collection in countries where HIV has spread to the general population.

For countries that have HIV epidemics mainly confined to key populations, data from HIV prevalence studies among those key populations are most often used. These prevalence studies are combined with the estimated number of people in those key populations—an estimate that is difficult to make, given that behaviours of key populations are outlawed in many countries.

In countries in which doctors are required to report cases of HIV, and if those data are reliable, those direct counts are used to estimate the epidemic. An increasing number of countries are setting up systems that use reported cases of HIV diagnoses.

Survey types

Population-based survey: a survey that is conducted in a random selection of households in a country. The survey is designed to be representative of all people in the country.

HIV prevalence study: a study of a specific population that collects blood samples from the population to determine how many people in that population are living with HIV. Typically, the results of that test are provided to the survey respondent.

Number crunching

Once a year, the country’s reporting agency will, helped by UNAIDS and partners, make estimates of the number of people living with HIV, the number of people on HIV treatment, the number of new HIV infections, etc., using software called Spectrum, which uses sophisticated calculations to model the estimates.

For estimates relating to children, a whole range of information, such as fertility rates, age distributions of fertility and the number of women in the country aged 15–49, is taken into account when computing the final numbers.

Estimates for different populations and age groups are calculated by Spectrum, taking into account different types of demographic and other data, building up a comprehensive picture of the country’s HIV epidemic.

The Spectrum estimates are sent to UNAIDS at the same time as the collection of the annual Global AIDS Monitoring reporting on the response to the HIV epidemic in the country. UNAIDS compiles and validates all the Spectrum files and uses the country-level data to make global estimates of the HIV epidemic and response.

UNAIDS publishes estimates for all countries with populations greater than a quarter of a million people. For the few countries of that size that do not develop Spectrum estimates, UNAIDS develops its own data, based on the best available information.

Ranges are important

In 2015, there were 36.7 million [34.0 million–39.8 million] people living with HIV in the world. The numbers in the brackets are ranges—that is, we are confident that the number of people living with HIV is somewhere within the range, but can’t say for sure what the definite number is.

All UNAIDS data have such ranges, but why can’t we be more accurate? UNAIDS data are estimates, which vary in their accuracy, depending on several factors. The size of sample taken for the estimate affects the range—a large sample means a small estimate range, and vice versa; if a population-based survey is conducted in a country, the estimate range will be smaller; and the number of assumptions made for an estimate has an impact on how narrow the range will be.

If it’s found to be wrong, it’s fixed

UNAIDS’ models are regularly updated in response to new information. For example, this year’s data will show a slight rise in the reported number of children becoming infected with HIV. This isn’t a real rise in young children acquiring HIV, but an adjustment in our knowledge of how infections occur in real life—in fact, once we apply this updated knowledge to previous years, we see that the number of new HIV infections among infants was higher then too.

Our new knowledge shows us that, after childbirth, higher numbers of women who are breastfeeding are becoming infected with HIV and hence passing the virus on to their children. Models had not fully captured the length of time for which women breastfed and were therefore at risk of passing on the virus through their milk if they became infected with HIV. With the model adapted to take into account women breastfeeding for longer than one year, the number of infants contracting HIV increased slightly for all years since the start of the epidemic.

Because of such finetuning, estimates from one year can’t be compared with estimates from a previous year. When UNAIDS publishes its yearly data, we revise all previous years’ estimates, taking into account the revised methodology. For example, the estimate published in 2006 for the worldwide number of people living with HIV in 2005 was 38.6 million—this was before we had incorporated national household surveys into estimates. By 2016, with the additional information from surveys, the number for 2005 had been revised to 31.8 million. Likewise, the estimate for AIDS-related deaths in 2005 was 2.8 million, which, by 2016, had been revised down to 2.0 million in 2005.

This finetuning has steadily improved the accuracy of our estimates, with the result that recent revisions are becoming smaller—the estimated number of people living with HIV in 2013 made in 2014 was 35.0 million, not far off the current estimates of 35.2 million.

UNAIDS data

Related information

Related

Feature Story

A global law firm, UNAIDS, justice and the SDGs: partnering for the 2030 Agenda

12 July 2017

12 July 2017 12 July 2017What do global law firm DLA Piper and UNAIDS have in common? Surprisingly, a lot. Both are working towards meeting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, both recognize the importance of the rule of law to development and equality and together they are working to strengthen legal protections and access to justice for people living with HIV and key populations.

DLA Piper is a global business law firm with offices in more than 40 countries and has one of the world’s largest pro bono practices led by a dedicated team of lawyers. In 2016, it donated more than 230 000 hours to pro bono and community projects. Rule of law and access to justice is at the heart of its work.

DLA Piper and UNAIDS have been collaborating for more than five years, assisting countries to improve their legal protections for people living with HIV and key populations. Before the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) existed, DLA Piper and UNAIDS were working together on the intersection between ending the AIDS epidemic (SDG 3), access to justice and the rule of law (SDG 16) and developing their public–private partnership (SDG 17).

With a new focus on the rule of law in the global community, and the importance of innovative partnerships, DLA Piper and UNAIDS have strengthened their collaboration. In 2017, DLA Piper seconded a full-time human rights lawyer to UNAIDS headquarters and UNAIDS and DLA Piper continue to explore new ways of working together to create a legally empowering environment for people living with HIV and key populations.

Quotes

Thanks to the work of lawyers at DLA Piper we can provide even greater support to countries looking to build an enabling legal environment for people living with HIV and reduce legal and human rights barriers for preventing and treating HIV among the most vulnerable. UNAIDS' collaboration with DLA Piper shows that innovative partnerships and approaches --such as with law firms -- can play a critical role in supporting efforts to ending the AIDS epidemic.

“Without strong institutions, without access to justice and rule of law, people will be left behind. UNAIDS recognizes the importance of this, and of putting human rights and equality at the heart of its work. We’re proud to be working with UNAIDS to ensure individuals have the legal empowerment and protection they need to realize their right to health and a life of dignity.”

Resources

Related

Feature Story

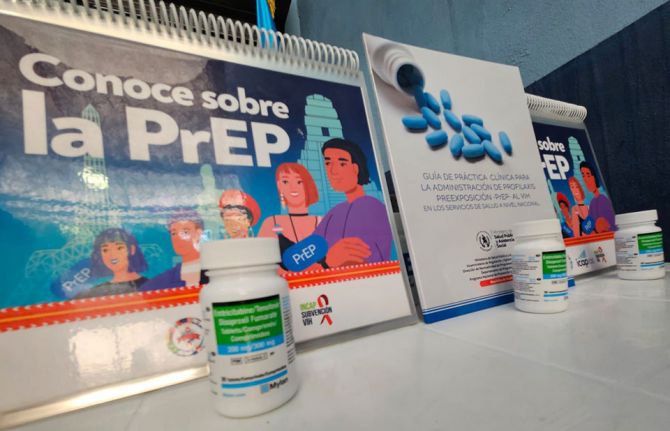

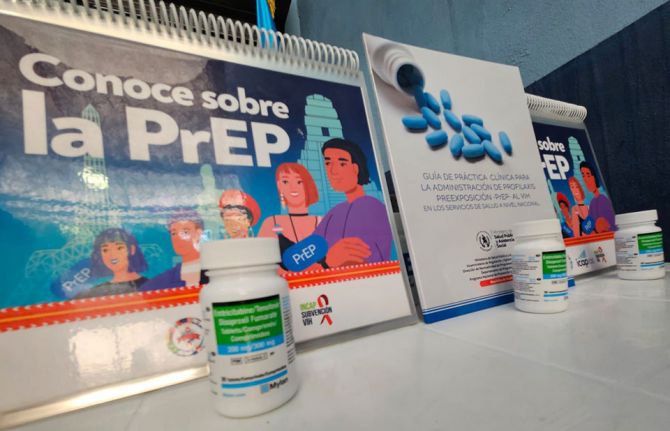

How do you do it? Australian HIV campaign puts emphasis on a combination of ways

05 April 2017

05 April 2017 05 April 2017Meet Tom, Dick and Harry. Sydney-based health promotion organization ACON’s current campaign singles out different men who “do it”, but who opt for different ways of protecting themselves. Australia’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people organization aims to stay in step with its community by redefining HIV prevention.

“We all have notions of what safe sex means, but we wanted to reflect actual behaviour among gay men and other men who have sex with men,” said ACON Chief Executive Officer Nicolas Parkhill.

Safer sex now means condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), an undetectable viral load or a mix, he explained.

“ACON’s challenge was going from the tried and true condom reinforcement only image to a much more complex combination prevention message,” Mr Parkhill said.

The campaign also stresses the importance of respecting a partner’s choice. “There should be no shaming of people who still use condoms,” Mr Parkhill said. In addition, he says, the combination prevention message speaks to people who are HIV-negative and people living with HIV.

In the campaign video, three men explain how they practise safer sex. One “does it all the time” and opts for condoms, while another says he “does it daily” by taking antiretroviral medicines and achieving an undetectable viral load. A third “does it every day” by taking a daily dose of PrEP.

The scenarios are based on men within the community, but ACON gave them the Tom, Dick and Harry placeholders of unspecified people. The AUS$ 500 000 #YouChooose campaign includes posters, billboards, videos, on-the- ground events and materials distributed to health clinics.

In existence for more than 30 years, ACON’s aim is to end HIV transmission among gay men and other men who have sex with men and promote the health of LGBTI people and people living with HIV. The organization is primarily funded by the New South Wales Government and works closely with the New South Wales Ministry of Health.

“The government values the voice of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex community in helping define what the HIV response needs to look like,” Mr Parkhill said.

UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director Luiz Loures agrees. “Communities need to be at the centre of initiatives for success in HIV prevention and ACON in Australia is putting key populations exactly at the centre,” he said.

And by having the community involved, Mr Parkhill says, the campaign goes beyond posters on bus shelters. “We are building a movement for gay men and the broader lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex community that believes we can put HIV behind us, and we have the science and technology available to do that.”

Community organizations look to UNAIDS for leadership and direction. The 90–90–90 targets provided ACON with the political leverage needed in Australia to engage with members of parliament to reshape and reenergize the direction of HIV testing, treatment, care and support. This provided it with the evidence and information that laid the foundation of its campaign to end AIDS.

Feature Story

Harm reduction programmes: saving lives among people who inject drugs

21 June 2017

21 June 2017 21 June 2017Harm reduction programmes are saving lives among people who inject drugs. Unfortunately, not everyone in need of such services has access to them. UNAIDS has produced a series of videos to raise awareness about harm reduction and to call for the provision of harm reduction services to all in need.

People who inject drugs are among the key populations most at risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Yet they are also among those with the least access to HIV prevention, care and treatment services, because their drug use is often stigmatized and criminalized.

Estimates show that worldwide there are approximately 12 million people who inject drugs, 1.6 million (14%) of whom are living with HIV and 6 million (50%) of whom are living with hepatitis C. HIV prevalence among women who inject drugs is often greater than among their male peers. UNAIDS estimates that 140 000 people who inject drugs were newly infected with HIV globally in 2014 and there was no decline in the annual number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs between 2010 and 2014.

The tools and strategies required to improve the health and lives of people who use drugs are well known and readily available. Needle–syringe programmes reduce the spread of HIV, hepatitis C and other bloodborne viruses. Opioid substitution therapy and other evidence-informed forms of drug dependence treatment curb drug use, reduce vulnerability to infectious diseases and improve uptake of health and social services.

The evidence is overwhelming—harm reduction works. Opioid substitution therapy has been associated with a 54% reduction in the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs and has been shown to decrease the risk of hepatitis C infection, to increase adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV, to lower out-of-pocket health expenditures and to reduce opioid overdose risk by almost 90%.

In Australia, 10 years of needle–syringe programming has reduced the number of cases of HIV by up to 70% and decreased the number of cases of hepatitis C by up to 43%.

The evidence is also clear that laws and policies that hinder access to health services for people who use drugs do not work. For example, police surveillance of health-care and harm reduction service providers discourages people who inject drugs from accessing those services.

Having laws that offer alternatives to prosecution and imprisonment for drug use and possession of drugs for personal use reduces the harmful health effects associated with drug use and does not result in an increased use of drugs.

Community-led harm reduction programmes can reach people who inject drugs with needle–syringe exchange and other services and provide linkages to testing, treatment and care for people living with HIV. In Pakistan, for example, the Nai Zindagi Trust, a peer-led outreach programme, has been in operation for 25 years and reaches about 13 000 street-based people who inject drugs through more than 600 trained peer educators.

Despite the large body of evidence, however, only 80 of the 158 countries in which injecting drug use has been documented have at least one location offering opioid substitution therapy, and only 43 countries have programmes in prisons. Needle–syringe programmes are available in only 90 countries and only 12 countries provide the recommended threshold of 200 sterile needles per person who injects drugs per year.

The combination of unavailability of harm reduction services and inadequate coverage where available puts progress in the response to HIV at risk. It also denies life-saving health services to millions of people who inject drugs.