Community mobilization

Feature Story

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

18 February 2025

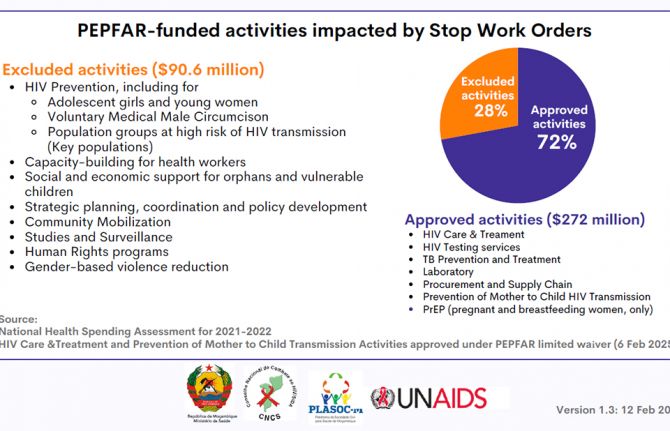

18 February 2025 18 February 2025On 20 January 2025 the United States announced a 90-day freeze on US foreign aid which has had a devastating impact on people living with and affected by HIV, on the people and organizations supporting them and on the global response to HIV as a whole.

Community organizations have been particularly impacted by the freeze in funding. Community healthcare workers are losing their jobs, clinics are having to be shut down and, as a result, people in need of HIV testing or prevention or who are living with HIV and dependent on daily antiretroviral medicine are unable to access the life-saving HIV services they need.

On 10 February, UNAIDS convened an emergency meeting with community organizations to monitor the impact of the unfolding crisis. Community groups reported that HIV services around the world are facing serious challenges. Some are grinding to a halt. Supplies of antiretroviral medication, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and condoms have been disrupted, leaving many without essential tools of HIV treatment and prevention.

HIV testing kits are increasingly scarce and outreach services – essential for connecting people in need of HIV testing – are being suspended. As a result, HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing are disrupted, threatening detection and prevention efforts.

“The damage is immediate and severe,” said one advocate. “People who rely on [U.S.-funded] programmes for [safety and] survival are suddenly left with nothing.”

The US pause in administering foreign assistance while it reviews recipients is not just a bureaucratic delay; it is a direct threat to continued progress against AIDS and will quickly erode decades of hard-won gains in the global HIV response. It will destroy many community organizations without which the world cannot close the gaps in HIV testing, prevention and treatment.

The US Government has invested more than US$ 100 billion to date in the global fight against AIDS with the US accounting for around 73% of donor funding for HIV worldwide; millions of people at risk for and living with HIV rely on US funded clinics to stay healthy in the face of HIV.

Community-led data reveals community organizations are bearing the brunt of the pause

A survey conducted by the Uganda Key Populations Consortium found that 97% of respondents reported negative effects on their HIV service due to the freeze on US foreign assistance. A staggering 43% of organizations supporting key populations surveyed said they relied on US funding for at least 76% of their budgets.

Another joint survey by Aidsfonds, the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), and the Robert Carr Fund found similarly worrying results. Of 564 organizations surveyed across 25 countries, 95% reported direct impacts from the US funding freeze. 43% of programmes have paused implementation, while 35% have fully suspended operations.

“The results are alarming,” said Mark Vermeulen, Director of Aidsfonds. “More than half (57%) of the organizations estimate that this crisis will impact more than a million people. The longer these disruptions persist, the greater the risk of a new generation of preventable HIV infections. This threatens to undo the hard-earned progress in reducing new infections among children.” (New HIV infections among children had been reduced by 62% from 2010 to 2023, largely thanks to investment and commitment from the US Government).

It’s not just people living with or at risk for HIV that face an existential threat

The financial void left by the US aid freeze of its foreign assistance is forcing community groups to fire employees and/or to close up shop entirely. Many community organizations do not have sufficient funding reserves to stay afloat through the 90-day (or perhaps longer) period of no US funding.

“The leadership of national networks of people living with HIV have been forced to let go of community cadre staff- peer educators, adherence counselors, community health facilitators, and mentor mothers,” said Florence Anam, Co-executive Director of GNP+.

GNP+ recently convened with leaders from national and regional networks of people living with HIV and released a statement with the main concerns.

“These organizations are not a luxury – they are critical for ending AIDS,” said Christine Stegling, Deputy Executive Director, UNAIDS. “Serving as advocates, peer educators, care providers and watchdogs, community-led organizations ensure that lifesaving HIV testing, prevention and treatment reaches those most in need.”

Many organizations have spent years garnering the trust of the communities they serve. If these organizations disappear, even if others replace them one day, it will take years to reestablish the bonds of trust that allow them to be so instrumental in encouraging people to seek HIV care.

In a joint survey by Aidsfonds, GNP+ and the Robert Carr Fund 22% of organizations reported increased experiences of discrimination, including reports of discrimination within healthcare settings, where people faced barriers to accessing care.

LGBTQ+ communities in need of HIV testing, prevention and treatment fear increased risks of violence and discrimination as funding for protective services – led by HIV community groups – disappear.

Since the earliest days of the AIDS pandemic, communities and community-led services have been instrumental in ensuring equitable, accessible HIV testing, prevention and treatment – as well as the supportive services that make all three possible.

Communities have been at the forefront, driving the delivery of comprehensive care, life-saving treatment and offering regular monitoring and prevention services and psychosocial support. Their unwavering dedication has not only saved millions of lives but also reshaped the trajectory of the AIDS pandemic. Their leadership and work on HIV are a model for all other responses to communicable diseases.

By paralyzing frontline response efforts led by community groups, the US decision to freeze funding is weakening health systems across the Global South. The freeze not only jeopardizes precious gains made to date against HIV – it also threatens to usher in a new wave of entirely preventable HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths.

The community groups stressed that this crisis extends beyond HIV treatment. The funding cuts impact efforts to provide clean water, basic education and to prevent human trafficking of girls. The loss of funding is dismantling the fragile safety net that has been built over decades around the world

“We are deeply concerned about the sustainability of the HIV response, particularly support for key populations, HIV prevention, human rights and community led responses. We are re-orienting our own efforts to support the communities and organizations that are both bearing the brunt of the loss of funding and facing targeted attacks on their rights and their very lives,” said John Plastow, Executive Director of Frontline AIDS, a global partnership, headquartered in the UK and South Africa, that works with 60 partners across 100 countries around the world. Over 20 of their partners have said they are affected by the US foreign aid freeze.

Since the US funding freeze on foreign assistance was announced, UNAIDS has conducted daily assessments led by its regional and country teams to track disruptions and to relay urgent needs to donors and to governments of affected countries. At country and regional levels, UNAIDS has also been convening people living with HIV and other affected communities to assess the impact and discuss mitigation measures. For the latest updates: Impact of recent U.S. shifts on the global HIV response - The global impact of PEPFAR to date | UNAIDS

UNAIDS stands in solidarity with community leaders calling on the US, other donors and governments of affected countries to step in before irreversible damage is done. UNAIDS and communities call on the US to maintain its global leadership on, and unparalleled support for the global response to AIDS. Without immediate intervention, decades of progress in the global HIV response will be undone, leaving the world on the precipice of a public health disaster that we have the power and tools to avert.

Press Release

Zambian football star Racheal Kundananji named UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Education Plus in Zambia

23 January 2025 23 January 2025GENEVA/LUSAKA, 30 January 2025—Zambian football star Racheal Kundananji has been appointed as a UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador to champion the fight to end AIDS as a public health threat in Zambia.

In her new role, Ms Kundananji will work with UNAIDS to champion HIV prevention, advocate for girls’ education to help reduce new HIV infections and sexually transmitted infections. She will also highlight the importance of preventing teenage pregnancy and advocate for an increase in HIV testing and access to health services for young people.

“I am so happy to be collaborating with UNAIDS to end AIDS as a public health threat in my country Zambia,” said Ms Kundananji. “Achieving this will require a collective effort, including ensuring that all young people in Zambia, particularly girls, remain in secondary education to reduce their risk of HIV infection and provide them with better economic opportunities.”

Ms Kundananji is already using her platform to drive change. She founded the Racheal Kundananji Legacy Foundation to harness the power of sport to address gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive health, and child marriage, demonstrating her deep commitment to empowering women and girls and tackling gender inequality.

“Ms Kundananji shares UNAIDS’ vision of ending AIDS as public health threat in Zambia by 2030,” said Isaac Ahemesah, UNAIDS Country Director for Zambia. “That world is possible. Leaders must ensure that girls stay in school and increase political and financial support to end the AIDS epidemic, by stopping new HIV infections and ensuring that everyone who needs treatment for HIV has access.”

United Nations Resident Coordinator for Zambia, Ms. Beatrice Mutali, praised Ms Kundananji’s dedication to advancing and promoting HIV awareness, testing, prevention and the Education Plus Initiative, which promotes girls’ school attendance. She also called for gender equality in sports, emphasizing the need for equal pay for equal work for women and men in all fields.

Ms Kundananji shattered the global women’s football transfer record, becoming the most expensive player in the history of women’s football. She is the first African footballer - male or female - to break the world transfer record. Now playing for Bay FC, an American professional women's soccer team based in the San Francisco Bay Area, she competes in the prestigious National Women's Soccer League, solidifying her place as a trailblazer on the global football stage.

Ms Kundananji has represented the Zambian National team since 2018 at the African Cup of Nations, FIFA World Cup Qualifiers and the Olympic qualifiers. Ms Kundananji has also played for Madrid Club de Fútbol Femenino among others.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Region/country

Press Release

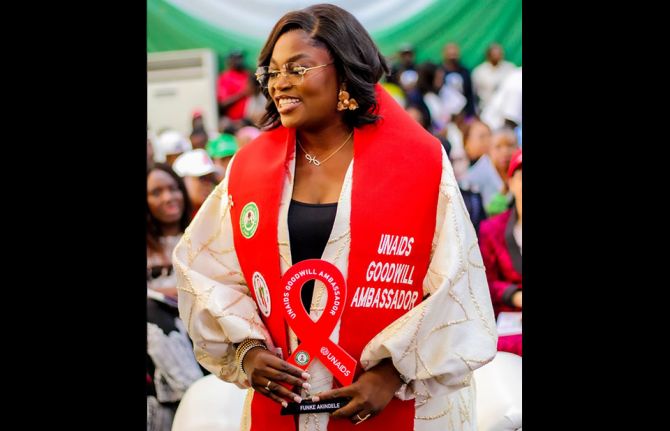

UNAIDS appoints artist Funke Akindele as National Goodwill Ambassador for Nigeria

03 December 2024 03 December 2024ABUJA, NIGERIA, 3 December 2024 — The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) is pleased to announce the appointment of Funke Akindele, a multiple award-winning actress, movie producer and director, as its new National Goodwill Ambassador (GWA) for Nigeria. This prestigious nomination recognizes Funke Akindele’s outstanding contributions to the fight against HIV and her unwavering commitment to advocacy, raising awareness, and driving efforts to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Funke Akindele’s career took off with her role in the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)-sponsored television series “I Need to Know”, which focused on adolescent reproductive health and rights, including HIV. Since then, she has captivated audiences worldwide, earning millions of fans and accolades for her unforgettable roles. Known as the “Queen of Box Office” in Nollywood, Funke holds the top three slots on the list of highest-grossing Nollywood films of all time, reflecting her prominence and influence in the industry.

Over the past two decades, Funke Akindele has consistently broken barriers and used her platform to amplify social impact issues, influence positive change, and champion causes that matter. As UNAIDS’ National Goodwill Ambassador, she will contribute to efforts aimed at eliminating vertical transmission of HIV, ending HIV-related stigma and discrimination, and promoting HIV prevention across Nigeria.

Nigeria has made significant strides in the fight against HIV over the past two decades. As of 2023, approximately 2 million people are living with HIV in the country, with an adult prevalence rate of 1.3% among individuals aged 15–49. Nigeria recorded approximately 130,000 new HIV infections in 2010. By 2023, this number had declined to about 75,000 new infections, representing a reduction of approximately 55,000 cases, or a 42.3% decrease over the 13-year period. . The country has also achieved notable progress in treatment access, with 1.6 million out of the 2 million people living with HIV in Nigeria currently on treatment.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain, including addressing stigma and discrimination, and ensuring equitable access to prevention and treatment services across all regions.

“We are thrilled to welcome Funke Akindele as our National Goodwill Ambassador for Nigeria,” said Dr Leopold Zekeng, UNAIDS Country Director for Nigeria. “Her powerful voice, vast influence, and commitment to social change make her an invaluable ally in our efforts to combat HIV and support people living with HIV in Nigeria. We look forward to working with her to drive positive impact and progress in the fight against AIDS.”

The nomination process for the National Goodwill Ambassador involved active collaboration with the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA), which has expressed appreciation for UNAIDS’ role in securing such a significant partnership for Nigeria’s HIV response. Funke Akindele’s work as a National Goodwill Ambassador will be vital in mobilizing efforts for HIV prevention and ensuring that key messages reach wider audiences across the country.

The official announcement of Funke Akindele’s appointment as UNAIDS National Goodwill Ambassador was made during the World AIDS Day commemoration in Abuja on 3 December 2024, during an event led by the United Nations Resident Coordinator for Nigeria, Mr. Mohammed M. Malick Fall.

Region/country

Feature Story

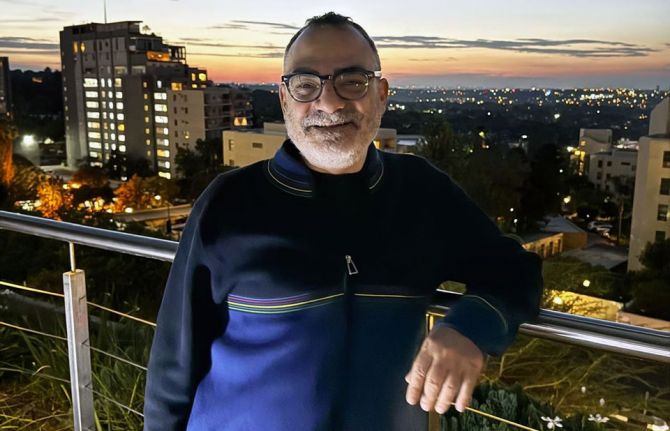

Christoforos Mallouris: From personal struggle to collective strength

29 November 2024

29 November 2024 29 November 2024Christoforos Mallouris' journey from humble beginnings in Cyprus to becoming a prominent global HIV advocate is a powerful story of personal transformation.

In his youth, Mallouris struggled with accepting his sexuality. "I couldn’t admit to myself that I was gay," shares Mallouris. The burden of self-stigma made it difficult for him to value his life: "In a way, I was homophobic towards myself and others."

At 29, while studying in Chicago, he was diagnosed with HIV. The diagnosis marked a pivotal moment in his life. "It changed how I understood myself, really forcing me to learn to value my life and accept who I am."

By the time he was diagnosed, he had already developed AIDS. Fortunately, Mallouris got support from his sister, who came to take care of him during his lowest moments.

Being HIV-positive in the United States as a foreign student presented its own set of challenges. "At the time, being HIV positive in the United States as a foreigner was illegal," Mallouris recalled, "so if the authorities found out, I would be deported." The fear of deportation hung over him as he was doing his PhD in astrophysics, but that fear also catalyzed his first act of activism.

Faced with health insurance that covered only two months of his costly HIV medication, Mallouris approached the Dean of Students at the University of Chicago. He boldly stated, "What are you going to do about it? I’m sure you don’t want this to go to the press." To his surprise, the Dean took immediate action, negotiating better health insurance coverage for all students with chronic illnesses.

As Mallouris’ health improved, he began to question his career path. Although he had completed his PhD in astrophysics, he no longer felt fulfilled enough by that field. He sought something that connected directly to being able to help people.

After securing a postdoctoral position at the Institute of Astrophysics in Paris, Mallouris found himself increasingly drawn to HIV work, so he started volunteering at a local NGO focused on HIV education and prevention for non-French speakers in Paris. It wasn’t long before he realized that this work was where his heart was.

He joined the Global Network of People Living with HIV, managing community empowerment programs in the HIV response. "I changed my career because of my HIV status," he said. "I wanted to do something that truly impacts lives."

Mallouris has had to overcome stigma and discrimination throughout his journey. Dating, for instance, was difficult. "There was a lot of rejection as soon as people found out I was HIV-positive," he shared. But despite the challenges, he found strength in the support of his friends, who have stood by him unconditionally. "I am lucky to have a strong network of support."

Mallouris joined UNAIDS in 2013, first as a Community Mobilization Advisor in Geneva and later as an Equality and Rights Advisor in Johannesburg. He describes UNAIDS as a supportive and inclusive workplace, where he feels valued for his skills and experience.

Mallouris highlights that the work to help secure treatment for people living with HIV is inseparable from the work to secure the recognition of people living with HIV as equal human beings. "Success in the HIV response depends on accepting all people, especially the most marginalized members of society.”

Mallouris is proud as he looks back, and hopeful as he looks ahead. He will always speak out for the rights of communities, even when—especially when—it isn’t popular.

HIV may have started as a burden in his life, but over time, it has become his strength, guiding him towards work that makes a profound difference, advancing a world where everyone is safe, has a place, and is welcome.

Press Release

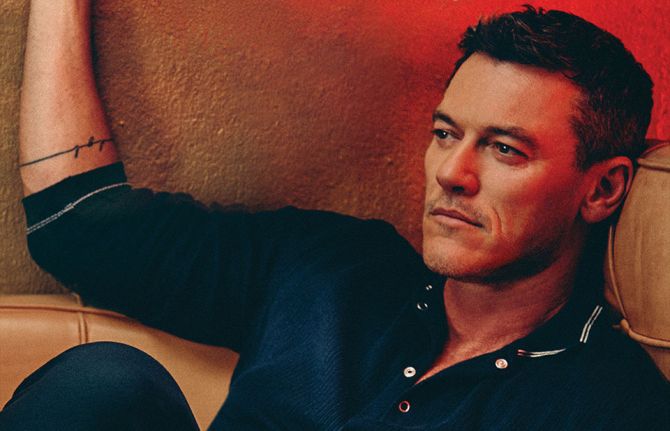

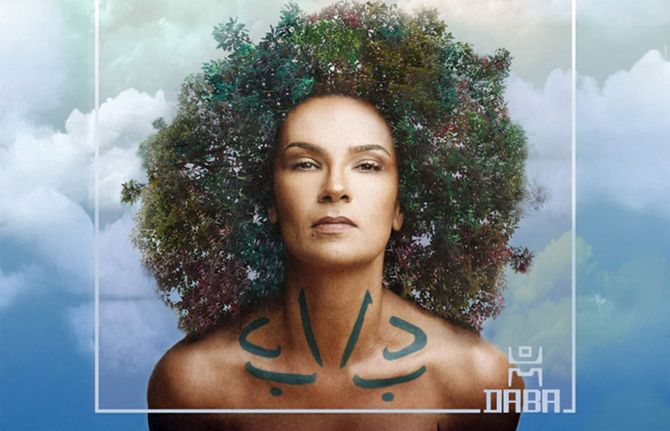

Global celebrities unite behind UNAIDS’ call for world leaders to “take the rights path to end AIDS”

01 December 2024 01 December 2024GENEVA, 1 December 2024 — This World AIDS Day (1 December), sixteen global celebrities, including Hollywood film star Luke Evans and singer-songwriter Sia of the Unstoppable hit song, are uniting behind UNAIDS’ call for world leaders to protect human rights, which they say is vital to ensuring the success of efforts to end AIDS.

The celebrities, including actress and comedian Margaret Cho; comedian and poet Alok Vaid-Menon; fashion designer and television personality Tan France; actor Alan Cumming; actor, broadcaster and comedian Stephen Fry; actress Uzo Aduba; Moroccan artist OUM; South African actress Thuso Mbedu; Chinese actor and singer Huang Xiaoming; professional football player Racheal Kundananji; Pakistani-British actor and comedian Mawaan Rizwan; Filipino model and actress Pia Wurtzbach; Ukrainian singer and TV show host Vera Brezhneva; and popular television presenter Erkin Ryzkullbekov have come together in support of UNAIDS call to “Take the rights path to end AIDS.”

“The choice is clear if we want to end AIDS as a public health threat. World leaders must take the rights path to protect people’s right to health and life. When human rights are respected and guaranteed, their lives are greatly improved because they can freely seek healthcare, including HIV prevention and treatment.” said Stephen Fry, broadcaster and comedian.

“In far too many countries, people are still criminalized for being who they are or for who they love. When LGBTQ+ people are criminalized, they are driven underground and out of reach of health services, including services to prevent and treat HIV.” said Alok Vaid-Menon, American comedian and poet.

The report highlights gaps in the realization of human rights and shows how violations of human rights are obstructing the end of the AIDS pandemic.

63 countries still criminalize LGBTQ+ people.

Discrimination against girls and women, from denial of education to denial of protection from gender-based violence, is also undermining progress in the global HIV response. In 2023, women and girls accounted for 62% of new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa.

“We all win the fight against AIDS when human rights and the right to health are secured for everyone everywhere. We can end AIDS as a public health threat by promoting rights, respect and dignity for all." said, Margaret Cho, actress and comedian.

“When girls cannot get access to education and information, when young women cannot access HIV prevention and testing, they are put at much greater risk of acquiring HIV,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS.

In 2023 alone, 1.3 million people around the world were newly infected with HIV—three times higher than the global target set for 2025 of no more than 370 000 new infections.

“To protect everyone’s health, we need to protect everyone’s rights,”

UNAIDS World AIDS Day report, “Take the rights path to end AIDS”, shows that the world can end AIDS—if the human rights of people living with or affected by HIV are respected, protected and fulfilled, to ensure equitable, accessible and high-quality HIV services.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

World AIDS Day report 2024

Feature Story

To end AIDS, communities mobilize to engage men and boys

04 December 2024

04 December 2024 04 December 2024Michael Onyango rises before dawn in his Nairobi apartment and catches a train eight hours east to Kilifi, a coastal town north of Mombasa. Resorts populate Kilifi’s sandy beaches and narrow wooden boats dot the water. Onyango heads inland to meet with the Kilifi County health management team, before dashing to an assembly of peer outreach workers from across the districts of Kaloleni, Malindi and Kilifi North.

Onyango runs the Movement of Men Against HIV in Kenya (MMAHK), spearheading a community-led monitoring initiative in the region to address the high numbers of men and boys who lack access to HIV services. In Kenya, only 65 percent of the men and boys over 15 years of age who are living with HIV are on antiretroviral therapy, compared to 80 percent of women and girls. The trend is mirrored globally: in 2024, the WHO and UNAIDS released data that men lagged on progress in achieving the 95-95-95 targets. Worldwide just 83 percent of men living with HIV know their status; 72 percent are on treatment and only 67 percent are virally suppressed.

MMAHK, in collaboration with the Masculinity Institute (MAIN), the International Network of Religious Leaders (INERELA+Kenya) and the UNAIDS Kenya country office, came together to tackle these service gaps in Kilifi County, which surrounds the town of the same name. The area, home to around 1.5 million residents, extends westward from the Indian Ocean and supports livelihoods through fisheries, factories, cashew nut mills, and farming.

In Kilifi, peer data collectors have identified that health facilities need to change their opening days and hours to accommodate the work and school day.

Community organizers are also working to challenge harmful prejudices that assert that men visiting a health facility or seeking an HIV test are “weak”.

As they rapidly roll-out peer support groups to challenge these beliefs, Onyango has had flashbacks to the pandemic’s earlier phases, when in the 1990s he worked as a counselor in a Nairobi hospital. HIV treatment was not yet available. “Many men I met who found out they were positive would resign from their jobs, go to their rural homes, sell their property, and wait to die,” Onyango said.

In 2001, Onyango and others started MMAHK to create a safe space for men to talk about their health needs. MMAHK also ran community testing, workplace outreach and targeted advocacy with religious and cultural leaders. As grassroots initiatives challenged harmful gender norms, Onyango saw social stigma and self-stigma among men decrease across Kenya. But the past few years have seen a resurgence of harmful norms around masculinity.

Onyango shares that the shift in funding away from many community initiatives, which were seen as harder to measure than biomedical interventions, has hampered community engagement efforts. Both are needed, he says. For example, although HIV treatment and voluntary male circumcision are now available in Kenya, cultural factors prevent some men from accessing these services.

A regional strategy developed in 2022 by UNAIDS, WHO, UN Women and partners –“Male Engagement in HIV Testing, Treatment and Prevention in East and Southern Africa” – outlines four key approaches: Improve access to health for men and boys and decrease vulnerability; prevent HIV among men and boys; diagnose more men and boys living with HIV; and increase the proportion of men and boys accessing and adhering to antiretroviral therapy.

“Tackling harmful masculinity also has a ripple effect,” reflects Lycias Zembe, a UNAIDS advisor in Geneva. “Harmful gender norms affect everyone, and changing these norms creates a better environment for women and girls and for men and boys.”

Community initiatives like MMAHK remain key. To challenge gender norms, MMAHK positions service access as courageous, and educates men that discussing emotions is a sign of strength. At 63, Onyango shows no signs of slowing down: “We’re going to keep addressing self-stigma and figure out how to help men access the services that they need to stay healthy,” he said. “We don’t have any other option.”

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Empowering youth to lead Togo’s HIV response

31 October 2024

31 October 2024 31 October 2024In Togo, youth and adolescents living with HIV are stepping forward to lead the response against the AIDS epidemic. Through resilience, determination, and a collective vision, they have come together to form a new youth-led network called the Network of Positive Children, Adolescents and Youth Innovating for Renewal (REAJIR+), This grassroots initiative is dedicated to amplifying the voices of all children, adolescents and young people affected by HIV, and is a testament to the power of youth leadership in shaping their future. “We felt the need to create a space where young people living with HIV could be heard and represented,” says Sitsope Adjovi Husunukpe, Executive Director and one of the founding members of the network. “Many of us felt that our needs and concerns, although important, were not given priority in the development and implementation of policies and interventions relating to HIV prevention and care.”

The network’s creation was not without problems. In Togo, where leadership is often adult-driven, it took courage and determination to establish an organization run by and for young people. "Even though we faced difficulties, we knew we had to persist," explains Adjovi. "The environment wasn’t always supportive, but we kept believing in the vision of our network. We wanted to ensure that young people living with HIV, from all walks of life, had a space to advocate for their rights."

The need for young people to be involved in the response to HIV in Togo is clear. According to recent reports, only about 26% of young people aged 15-24 have enough knowledge about how to prevent HIV.[1] Children's performance in terms of adherence to HIV treatment is below the general average of 80.5%[2]. At the same time, 6,200 children aged 0 to 14 are living with HIV[3]. In Western and Central Africa, at least 16% of girls and 12% of boys aged 15-24 have sex before they turn 15[4]. These numbers show that more needs to be done to help young people understand HIV to protect themselves.

“Empowering young people goes beyond raising awareness; it’s about unlocking their potential to drive change. When they take ownership of their advocacy, they become catalysts for progress, shaping solutions that resonate in their communities. By equipping them with the right tools, we invest in a future led by those who understand the challenges firsthand.” says Dr Yayé Kanny Diallo, UNAIDS Country Director for Togo and Benin.

Koffi Emmanuel Hounsime, the network’s president, echoes the importance of youth-led advocacy. “At the beginning, people questioned our legitimacy. They asked, ‘Who are you representing?’ But once we formalized our network and built our credibility, we gained respect. Now, when we speak, we speak with authority on behalf of youth living with HIV across the country.”

Despite these hurdles, the network remains committed to its mission. “We are working not just for ourselves but for the future generation of young people living with HIV,” says Adjovi. "We want to ensure that we have better support, better care improving our life quality, and that we feel empowered to take decisions concerning our own well-being."

The network has already made significant strides. It has actively participated in national HIV dialogues and contributed to the development of the new Global Fund HIV grant, ensuring that the priorities of adolescents and young people are included.

For these young leaders, creating the network is about more than just advocacy. It’s about survival, empowerment, and hope. Emmanuel reflects, “We didn’t just create this network to represent young people, we created it to change lives. Every day, we’re working to make sure that no young person living with HIV feels alone.”

[1] AIDS INFO Togo Country Data

[2] Rapport REDES Togo 2023

[3] AIDS Info Togo Country Data

[4] UNESCO Education Report

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Bridging gaps: sex education saves lives in Central African Republic

03 September 2024

03 September 2024 03 September 2024In a modest neighborhood of Bangui, Central African Republic’s capital city, Gniwali Ndangou is rushing to work. She’s a peer educator and community health worker at a youth sexual education centre, CISJEU.

The same centre that saved her life.

I'm an orphan," she said, “I am the youngest of three sisters.” Throughout her childhood, her legal guardian told her to take pills saying it was anti-malaria and headache medicine. “I was the only one who took treatment every day and it never stopped.”

After threatening to stop taking pills when she was 17 years old, her sister finally told her the truth. She was born with HIV.

Gniwali couldn’t believe the litany of lies. Having recently been forced to quit school as her adopted family struggled to make ends meet, she once again felt abandoned.

“Many times, I tried to commit suicide… I wanted to end my life,” she said.

Her sister Astrid said she tried to pull her youngest sibling out of despair and kept hammering to her: “There are no differences between us, we are all humans.”

At her sister’s urging, Gniwali sought help at a youth center, Centre d’information et d’éducation sexuelle des jeunes (Center for Youth Sexual Education and Information) known as CISJEU. Established in 1994, CISJEU has been a beacon of hope for many young people like Gniwali. They offer community-led services ranging from HIV prevention to HIV testing to peer-supported treatment initiation and adherence.

War and extreme poverty have greatly increased premature death in Central African Republic, leaving seventy-eight percent of the population under 35 years old. Young people struggle to receive an education with less than 4 in 10 adults literate. Gender inequality and gender-based violence also make young girls particularly vulnerable to HIV infection. Out of the 10,000 yearly new HIV infections, 3000 are among 15-24 years old with more than two female infections for every one male infection.

According to a UNICEF survey, less than 20% of young people possess comprehensive knowledge about HIV prevention. The youth center uses peer educators to bridge this knowledge gap and provide youth-friendly services. "We've trained and deployed 160 peer educators (80 in schools while the others are at youth centers) across different districts of Bangui and beyond, ensuring effective outreach and health and body awareness," said Michael Guéret, a program officer at CISJEU.

Chris Fontaine, former UNAIDS Country Director, underscores the importance of peer-led initiatives, “Addressing HIV and sexual health among young people in CAR is not just a health issue but a critical component of sustainable development and peace consolidation.”

With support from UNAIDS and the Ministry of Health, CISJEU has attained the right to distribute HIV medicine, antiretroviral therapy, among the community.

For Gniwali, CISJEU became more than a sanctuary. Through training programs, she evolved from a beneficiary to a peer educator and community healthcare provider. “I received various certifications such as mobile HIV testing, and psychosocial support."

Leading discussion groups and dispensing life-saving antiretroviral medications to young people, she inspires young women to take care of their health. Her message is clear and powerful: "Being a young woman isn't easy. We must educate ourselves about this disease, fight against it, and prevent its spread in our country.”

Watch

Region/country

Documents

2024 global AIDS report — The Urgency of Now: AIDS at a Crossroads

22 July 2024

This UNAIDS 2024 report brings together new data and case studies which demonstrate that the decisions and policy choices taken by world leaders this year will decide the fate of millions of lives and whether the world’s deadliest pandemic is overcome. Related links: Press release | Special web site | Executive summary | Fact sheet | Video playlist | Epidemiology slides | Data on HIV | Annex 2: Methods Regional profiles: Asia and the Pacific | Caribbean | Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Eastern and Southern Africa| Latin America | Middle East and North Africa | Western and Central Africa | Western and Central Europe and North America Thematic briefing notes: People living with HIV | Gay men and other men who have sex with men | Transgender people | Sex workers | People who inject drugs | People in prisons and other closed settings | Adolescent girls and young women | Other translations: German

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

18 February 2025

UNAIDS urges that all essential HIV services must continue while U.S. pauses its funding for foreign aid

UNAIDS urges that all essential HIV services must continue while U.S. pauses its funding for foreign aid

01 February 2025

Feature Story

How communities led in the HIV response, saving lives in Eswatini at the peak of a crippling AIDS epidemic

25 April 2024

25 April 2024 25 April 2024This story was first published by News24.com

Eswatini is one of the countries which has been most affected by HIV. At the peak of the epidemic in 2015, almost one out of three people were living with HIV. In 1995, when there was no antiretroviral treatment for people living with HIV, 73 000 people were living with HIV. 2400 people died of AIDS that year. Worried about the rising number of infections and deaths, communities of people living with HIV mobilized to press that antiretroviral treatment be made available for people living with HIV.

One of the key campaigners for access was Hannie Dlamini. Dlamini is now 50 years old and has been living with HIV for 32 years, after finding out about his HIV positive status at the age of 18. He was one of the first people in Eswatini to publicly declare his positive HIV status in 1995 at a time when the stigma and misinformation around HIV was rife.

Dlamini rallied together other people living with HIV as well as non-governmental organizations working to end AIDS in Eswatini, to ensure that everyone living with HIV and in need of treatment had access to it. They formed a community-led organization called Swaziland AIDS Support Organization (SASO) as a support group for people living with HIV. SASO also provided healthy living information for people living with HIV.

“When we asked the government [in 2002] for ARVs in Eswatini we did a pilot project with NECHA [National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS], to see if people would use the drugs.” Dlamini says the response was overwhelming, with many people keen to start the lifesaving treatment. “We initially planned to enrol 200 people on treatment but the demand was 630.” said Dlamini.

Today, Eswatini is one of the countries which has achieved the ambitious 95-95-95 targets (95% of people living with HIV who know their HIV status, 95% of people who know that they are living with HIV are on life-saving antiretroviral treatment, and 95% of people who are on treatment are virally suppressed). This achievement has put the country a step closer to ending AIDS as a public health threat, thanks to the work of community-led organizations, authorities and global partners like UNAIDS, the United States President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria who are working with the government and local communities to end AIDS.

Eswatini’s HIV response strategy includes ongoing nationwide testing and treatment campaigns, use of self-testing kits to encourage more people to take up testing at the comfort of their homes, antiretroviral treatment, male circumcision and pre-exposure prophylaxis (medicine to prevent HIV) and other prevention measures. Community organizations such as Kwakha Indvodza are also key in encouraging men to take full responsibility for their wellbeing and reducing toxic masculinity and gender-based violence which are some of the drivers of HIV.

The driving role of communities in Eswatini to end AIDS is acknowledged by the health authorities. According to Dr. Michel Morisho, HIV management specialist at Mbabane Government Hospital, the government “could not have achieved the 95-95-95 without communities.”

Dr. Morisho says as part of the country’s strategy to end AIDS, HIV testing and treatment are part of disease management for every patient who presents at health facilities for any illness. “When people come to the hospital for whatever, or check up, we offer an HIV test to allow them to know their HIV status,” he said. Dr. Morisho added that treatment is important to bring down viral load and is helping people living with HIV to stay healthy. Eswatini is striving to achieve 100-100-100 [in the number of people who know their HIV status, are on treatment and are virally suppressed].” People who are virally suppressed cannot transmit HIV, thus helping in HIV prevention efforts.

Young women living with HIV have also stepped up to fight the spread of HIV in the country, volunteering their time as peer educators to educate young people about HIV and supporting people newly infected to stay on treatment to live healthily and long lives. Ntsiki Shabangu is a 28-year-old young woman living with HIV. She was diagnosed with HIV in 2015, at the age of 19. She opened up about her status in 2017 and is now working with the Eswatini Network of Young Positives, a local non-governmental organisation working to end AIDS among young people providing counselling and HIV awareness training . Ntsiki believes that: “When you share your story, you bring hope to young people.”

While Eswatini is on the path to end AIDS, the country is facing other health burdens associated with aging, including non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer. People living with HIV are not often more affected by these illnesses. Some people living with HIV in Eswatini have developed these comorbidities, which presents the need for the strengthening of the healthcare system to provide easily accessible holistic disease management and treatment along with HIV services to improve the quality of life for people living with HIV. As Thembi Nkambule, a woman who has been on HIV treatment for more than 20 years said: “Most of us are sick. Most of us are presenting with kidney issues. We are presenting with hypertension; we are presenting with sugar diabetes. We have a lot of issues.”

To protect the gains that have been made against HIV in Eswatini, the government should invest more resources in building a resilient healthcare infrastructure to strengthen the system to better meet the health needs of people living with HIV and to prepare for future pandemics. Community-led organisations should also be placed at the centre of HIV response and supported, both financially and politically, to reach more people who need HIV services to end the epidemic by 2030 as a public health threat.