HIV prevention and drug treatment for prisoners in the Republic of Moldova

prisons

22 July 2024

People in prisons and other closed settings are disproportionally affected by HIV. In 2023, HIV prevalence among people in these settings was two times higher than among adults aged 15–49 years in the general population. Lack of access to HIV treatment and prevention services in prisons and other closed settings remains a significant barrier to achieving social justice and equality and ensuring health for all people. Treatment coverage gaps are notable for people living with HIV in prisons and other closed settings. Among the 37 countries that reported on antiretroviral therapy coverage among people in prisons and other closed settings in recent years, only 18 countries reported above 95% coverage, and five countries reported less than 50%. HIV programmes are generally not available or tailored for women in prisons and other closed settings. A small but slowly increasing number of countries provide at least some HIV-related services in prisons and other closed settings. Related links: New UNAIDS report shows AIDS pandemic can be ended by 2030, but only if leaders boost resources and protect human rights now | Full report

02 December 2024

22 July 2024

22 July 2024

22 July 2024

This UNAIDS 2024 report brings together new data and case studies which demonstrate that the decisions and policy choices taken by world leaders this year will decide the fate of millions of lives and whether the world’s deadliest pandemic is overcome. Related links: Press release | Special web site | Executive summary | Fact sheet | Video playlist | Epidemiology slides | Data on HIV | Annex 2: Methods Regional profiles: Asia and the Pacific | Caribbean | Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Eastern and Southern Africa| Latin America | Middle East and North Africa | Western and Central Africa | Western and Central Europe and North America Thematic briefing notes: People living with HIV | Gay men and other men who have sex with men | Transgender people | Sex workers | People who inject drugs | People in prisons and other closed settings | Adolescent girls and young women | Other translations: German

27 February 2025

18 February 2025

01 February 2025

Harm reduction policies and practices help people who are using drugs to stay alive and protect them from HIV and Hepatitis C

Released ahead of International Harm Reduction Day - 7 May 2023

GENEVA, 5 May 2023—Many prison systems are struggling to cope, with overcrowding, inadequate resources, limited access to healthcare and other support services, violence and drug use. In 2021, the estimated numbers of people in prisons increased by 24% since the previous year to an estimated 10.8 million people, increasing the strain on already overstretched prison systems.

Drug use is prevalent in prisons. UNAIDS Cosponsor, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), estimates that in some countries up to 50% of people in prisons use or inject drugs. Unsafe drug injecting practices are a major risk factor for the transmission of HIV and hepatitis C due to limited access to harm reduction services, including condoms, clean needles and syringes, and a lack of comprehensive drug treatment programs, particularly opioid agonist therapy.

People in prison are 7.2 times more likely to be living with HIV than adults in the general population. UNAIDS reports that HIV prevalence among people in prisons increased by 13% since 2017, reaching 4.3% in 2021. Although data are limited, it is thought that around one in four of the total prison population has hepatitis C.

“Access to healthcare, including harm reduction services, is a fundamental human right, and no one should be denied that right because they are incarcerated,” said Eamonn Murphy, UNAIDS Regional Director for Asia Pacific and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. “Prisons are too often ignored in countries' efforts to respond to HIV. A multisectoral, multifaceted approach is urgently needed to save lives, which includes access to clean needles and syringes, effective treatment for dependence on opioid drugs and reducing stigma and discrimination.”

Both drug use and HIV infection are more prevalent among women in prison than among imprisoned men. In particular, women who use drugs and sex workers are overrepresented in prisons. Highlighting the urgent need to scale up the implementation of community-led harm reduction services for women who use drugs and women in prison.

Ms Ghada Waly, Executive Director of UNODC, said, “It is time to put compassion at the heart of our responses. To take a more serious look at de-penalization and alternatives to incarceration for minor drug offenses, focusing instead on treating and rehabilitating. To use a gender-sensitive lens when looking at women and girls who use drugs, and to ensure that they have equal access to treatment. To reach out to young people, who are using drugs more than ever before, understand their vulnerabilities to substance abuse, and help them be part of the solution. To stand with marginalized and vulnerable people, including people in prisons who are underserved by treatment programmes, and people who inject drugs, who are far more likely to be living with HIV, yet far less likely to access life-saving services”.

Among the countries reporting on prisons to UNAIDS in 2019, just 6 of 104 countries had needle and syringe programmes in at least one prison; only 20 of 102 countries had opioid substitution therapy programmes in at least one prison, 37 of 99 countries had condoms and lubricants in some prisons.

UNAIDS, UNODC, and WHO have long supported expanding harm reduction services to all prisons. However, according to Harm Reduction International, only 59 countries globally provide opioid agonist therapy in prisons.

Some countries have made huge progress in recent years. Despite the challenges faced by the influx of refugees and the repercussions of the war in Ukraine, Moldova, (which has an HIV prevalence of 3.2% in its prisons, compared to 0.4% among the general population) has committed significantly more resources into its prison systems.

In the early 2000’s few of its prisons provided harm reduction services. Today all of the country’s 17 penitentiaries provide harm reduction services including, methadone (an opioid agonist therapy), access to psychiatrists, doctors and treatment programmes, needle and syringe exchange and HIV prevention, testing, treatment and care.

Svetlana Plamadeala, UNAIDS Country Director in Moldova said, “It’s about putting people front and center, treating them as equals and taking on a solid, public health approach, grounded in human rights and evidence.”

UNAIDS, UNODC, UNFPA, WHO, ILO and UNDP recommend 15 comprehensive and essential interventions to save lives and ensure effective HIV programming in prisons. These include HIV prevention, testing and treatment, condoms, lubricant, opioid agonist therapy and post-exposure prophylaxis. However, this is only part of the solution. UNAIDS also recommends that countries amend their laws to decriminalize the possession of drugs for personal use.

UNAIDS has set ambitious targets for 2025 which include: 95% of people in prisons and other closed settings who know their HIV status, 95% who know their status are on treatment; and 95% on treatment are virally suppressed; 90% of prisoners used condoms at last sexual activity with a non-regular partner; 90% of prisoners who inject drugs used sterile needles and syringes at last injection; and that 100% of prisoners have regular access to appropriate health system or community-led services.

UNAIDS advocates that communities take an active role in planning, providing and monitoring HIV services. However, this is not always facilitated in prison settings. Without community engagement it will be impossible to reach the global AIDS targets.

For more information on Moldova’s work on HIV in prisons please read Moldova expands harm reduction services to all prisons and watch https://youtu.be/JQYtnsiJKs0

Fact sheet: UNAIDS Human rights fact sheet on HIV in prisons

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

14 May 2021

14 May 2021 14 May 2021“AIDS came to my door as a surprise. It all started in 1988, when my partner, Rafael, started to get sick. We were both 28 years old at the time,” said Georgina Gutiérrez, who has been a human rights activist for people living with HIV in Mexico for more than 30 years.

Today, she is a representative of the Mexican Movement for Positive Citizenship, which aims to promote the empowerment of people living with HIV in prison. She is also part of the Latin American and Caribbean Movement of Positive Women.

“In those years, stigma and discrimination were widespread. I knew about HIV only through television and many women who had HIV-positive partners assumed they were living with HIV without ever having been tested,” she said.

Her partner was imprisoned in Santa Martha Acatitla Penitentiary in Mexico City, where he spent eight years. This was when she got to know the reality inside prison, and it was this experience that would set the course of her life towards working with jailed people living with HIV.

“People living with HIV in prison are invisible to society. I remember many years ago, as a protest they would burn their mattresses, just to demand dignity in their access to HIV treatment,” Ms Gutiérrez recalled.

Ms Gutiérrez knew that there was a need for action to protect the physical and mental health of people living with HIV in prison. This is how she and others started a project against HIV and COVID-19 in the Santa Martha Acatitla Penitentiary.

The project is one of 30 initiatives selected from more than 190 applicants for the UNAIDS 2020 call for proposals for community-based organizations working on HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean that received funding. The project received an award of US$ 5000 to help its work.

The Santa Martha Acatitla Penitentiary houses around 2000 inmates, including 180 people living with HIV, some in the advanced stages of AIDS-related illnesses. People living with HIV are concentrated in Dormitory 10 in the prison.

“Dormitory 10 is overcrowded and physical distancing is difficult. Hygiene standards were low. In addition, most of them had not received COVID-19 personal protective equipment—the very few who were able to access such equipment did so through their families,” said Ms Gutiérrez.

In addition to the 180 people living with HIV in the prison, each of whom received personalized face coverings and other personal protective equipment and who attended a series of trainings, approximately another 1000 staff and inmates benefited from the project.

“I have been able to see them change. They have told me many times that they feel safer with the tools and knowledge they have gained,” said Ms Gutiérrez. “They feel good to know there are people concerned about them during this health crisis.”

“With our trainings and donations, the prisoners can now keep their rooms clean and can frequently wash their hands, clothes and personal belongings.”

Working for HIV prevention is, “A commitment I have in every drop of my blood,” she said. “With these actions, we are giving life to forgotten people. I thank UNAIDS for financing this project—with it we are supporting a population that is being left behind.”

On any given day, approximately 11 million people worldwide are incarcerated. The risk of sexual violence among prisoners—and their inadequate access to condoms, lubricants, pre-exposure prophylaxis and harm reduction services—increases their chances of contracting HIV, hepatitis C and other sexually transmitted infections.

22 February 2021

22 February 2021 22 February 2021On any given day, approximately 11 million people worldwide are in confinement. Drug injection and sexual intercourse occur worldwide in prisons. The risk of sexual violence among prisoners—and their insufficient access to condoms, lubricants, pre-exposure prophylaxis and harm reduction services—heighten their chances of acquiring HIV, hepatitis C and sexually transmitted infections.

Among people who inject drugs, recent incarceration is associated with an 81% and 62% increased likelihood of HIV infection and hepatitis C infection, respectively.

Closed settings should, in theory, favour the delivery of effective testing and treatment services, although treatment interruptions and concerns about confidentiality and discrimination pose challenges. In 2019, 78 countries reported to UNAIDS that HIV testing was available at any time during detention or imprisonment, and 104 countries reported that antiretroviral therapy was available to all prisoners living with HIV. Coverage of antiretroviral therapy is good, although gaps remain.

13 May 2020

13 May 2020 13 May 2020With more than 11 million people in custody worldwide, and 30 million people entering and leaving detention every year, the threat of COVID-19 for people in prisons is very real. In the vast majority of the world’s overcrowded and underfunded prisons and detention centres, physical distancing is simply not an option. In situations where close confinement, shared facilities and spaces and poor hygiene are commonplace, inmates and prison staff are living in constant fear of the ticking COVID-19 time bomb.

“A health response to COVID-19 in prisons is not enough. This unprecedented global emergency demands a response based on human rights,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “Countries must ensure not only the security but also the health, safety and human dignity of people deprived of their liberty at all times, irrespective of any state of emergency.”

UNAIDS, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the World Health Organization and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime are calling on leaders to make detention a last resort, to close drug rehabilitation detention centres and to decriminalize sex work, same-sex sexual relations and drug use. They are urging countries to release the people who can be released and to consider people at risk of COVID-19, such as older people and people with pre-existing health conditions. Other people, including people sentenced for minor, non-violent offences, pregnant women, women who are breastfeeding and children, should also be considered for release.

As reports of terrified inmates sewing makeshift masks continue to emerge, countries are starting to take action. The Government of Ethiopia, for example, has released more than 30 000 prisoners and has heightened sanitation measures. Indonesia is releasing more than 50 000 people, including 15 000 people incarcerated for drug-related offences. The Islamic Republic of Iran is releasing 40% of its total prison population,100 000 people, while Chile is set to release around 50 000 people.

14 March 2018

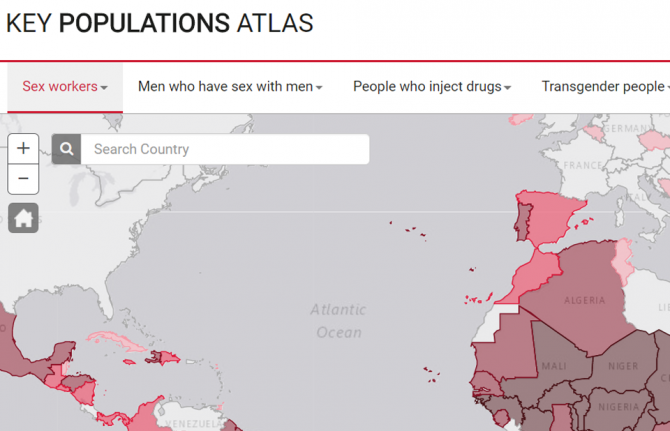

14 March 2018 14 March 2018UNAIDS has relaunched its Key Populations Atlas. The online tool that provides a range of information about members of key populations worldwide—sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, transgender people and prisoners—now includes new and updated information in a number of areas. And in addition to data on the five key populations, there are now data on people living with HIV.

Chief among the new data is information on punitive laws, such as denial of the registration of nongovernmental organizations, and on laws that recognize the rights of transgender people. The overhaul of the site was undertaken in consultation with representatives of civil society organizations, including the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, which supplied some of the new data on punitive laws.

Data on the number of users of Hornet—a gay social network—in various countries has been made available for the atlas by the developers of Hornet, while Harm Reduction International supplied information on the availability of harm reduction programmes in prisons.

“Having data on the people who are the most affected by HIV is vital to getting the right HIV services available at the right locations” said Michel Sidibé, the Executive Director of UNAIDS. “The Key Populations Atlas allows UNAIDS to share the information we have for the most impact.”

The Key Populations Atlas is a visualization tool that allows users to navigate country-specific subnational data on populations particularly vulnerable to HIV. Data are presented on, for example, HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in 11 sites in Myanmar, key populations sizes, antiretroviral therapy coverage among gay men and other men who have sex with men in 13 sites in India and specific prevention services and preventive behaviours. Updated data on many indicators that were obtained through the Global AIDS Monitoring exercise undertaken in 2017 is now available on the website.

Over the coming weeks, information on people living with HIV will be expanded, with new indicators being added, and data from the 2018 Global AIDS Monitoring will be added when available later in the year.

04 December 2014

02 June 2021

04 June 2020

13 May 2020

13 May 2020

23 October 2012

23 October 2012 23 October 2012

UNAIDS Executive Director, Michel Sidibé met with Indonesia’s Minister of Health, Nafsiah Mboi as part of his two-day trip to Indonesia.

Credit: UNAIDS/E.Wray

Indonesia’s Minister of Health, Nafsiah Mboi, pledged to scale up HIV testing and treatment programmes, leading to zero new HIV infections and zero AIDS-related deaths. Minister Mboi met with UNAIDS Executive Director, Michel Sidibé on Tuesday, on the first day of his two-day trip to Indonesia.

Indonesia is one of several countries in Asia where new HIV infections are growing. The Ministry of Health estimates that more than 600 000 people are living with HIV and that there are more than 76 000 new HIV infections each year. Currently HIV treatment coverage is at less than 20%.

But, Minister Mboi promised a new approach to the country’s AIDS response. She said she will ensure that everyone will know their HIV status and have access to HIV treatment. Health authorities will focus on 141 districts where key affected populations are the highest. Indonesia’s epidemic is concentrated on key populations at higher risk such as drug users, sex workers and their clients and men who have sex with men.

Universal health coverage is a game changer for Indonesia. I am delighted to know that HIV treatment will be included in this national programme. This sets the stage for sustainable funding of HIV programmes.

UNAIDS Executive Director, Michel Sidibé

Indonesia is taking an active role in the AIDS response in Asia. As chair of the last year’s ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) summit the country pushed for the adoption of the ASEAN Declaration of Commitment in Getting to Zero New HIV Infections, Zero Discrimination and Zero AIDS-related deaths.

Indonesia also plans to become one of several countries in the region to offer universal health care by 2014. The Ministry of Health says that HIV treatment will be included in the health coverage.

“Indonesia is a key partner in the drive to end the AIDS epidemic,” said Mr Sidibé. “Universal health coverage is a game changer for Indonesia. I am delighted to know that HIV treatment will be included in this national programme. This sets the stage for sustainable funding of HIV programmes.”

UNAIDS Executive Director, Michel Sidibé toured the Narcotics Prison Cipinang in East Jakarta where he met with prison authorities and visited the clinic where antiretroviral treatment and methadone services are provided.

Credit: UNAIDS/E.Wray

Domestic investments in the HIV response have been increasing significantly in Indonesia since 2010, but there still is a large funding gap and in 2015 Indonesia will no longer be eligible for funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis.

“Indonesia is trying to ensure the sustainability of HIV care for people living with HIV once donor countries stop giving funds,” said Minister Mboi. “The Ministry of Health is preparing an exit strategy. We plan to cover 100% of the HIV treatment by the national government budget,” she added.

Health authorities are increasing efforts to focus HIV programmes on communities that need the most attention. The sharing of needles among people who use drugs has been one of the drivers of the HIV epidemic in Indonesia. Since 2009, the Directorate General of Corrections says it has scaled up its HIV programmes at 149 corrections facilities in 25 provinces.

Mr Sidibé toured the Narcotics Prison Cipinang in East Jakarta, which is one of eleven model prisons implementing a comprehensive AIDS programme. He met with prison authorities and then went on a tour of the prison, visiting the clinic where antiretroviral treatment and methadone services are provided. He also toured the occupational training centre where inmates learn new skills including baking, sewing and handicrafts.

“My visit today shows that even in prisons we can restore the dignity of people,” said Mr Sidibé. “Prison can be a transformative experience. The Indonesian government is showing great innovation and courage with its remarkable harm reduction and HIV programme in prisons. I hope the programme inspires other countries to show the same entrepreneurship,” he added.

The Ministry of Health hosted a dialogue between Mr Sidibé and faith based organizations, including Islamic, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist and Confucian religious groups.

Credit: UNAIDS/E.Wray

On Tuesday, the Ministry of Health hosted a dialogue between Mr Sidibé and faith based organizations, including Islamic, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist and Confucian religious groups. Religious leaders are important community members and their cooperation is key to ensuring support for HIV prevention, treatment and care. The leaders agreed that faith based organizations need more education and training in HIV issues, so that they can help their communities.

Anggia Ermarini, Health Unit Secretary of Indonesia’s Ulama Council, the country’s Muslim clerical body said, “Many religious leaders do not understand about AIDS. We want the United Nationsto to tell us about the situation in our country.”

Franz Magnis Suseno, a Jesuit priest from the Institute of Philosophy Driyakara said that he thought that religious organizations needed to start to educate people about sexuality. He said there was a high resistance to sex education but that it was necessary.

Mr Sidibé is in Indonesia at the start of a three country trip to Asia, where he will also visit Myanmar and Thailand.