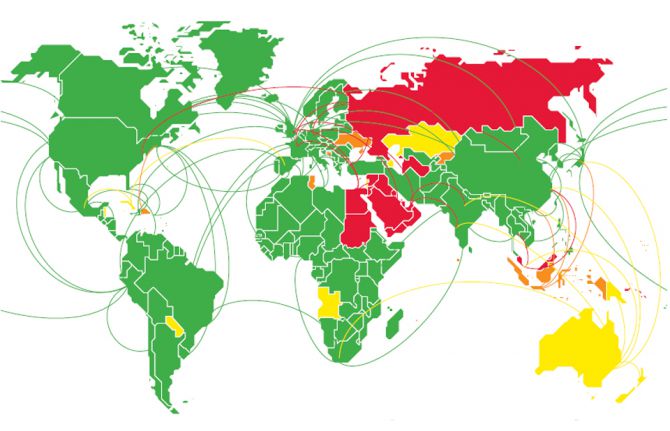

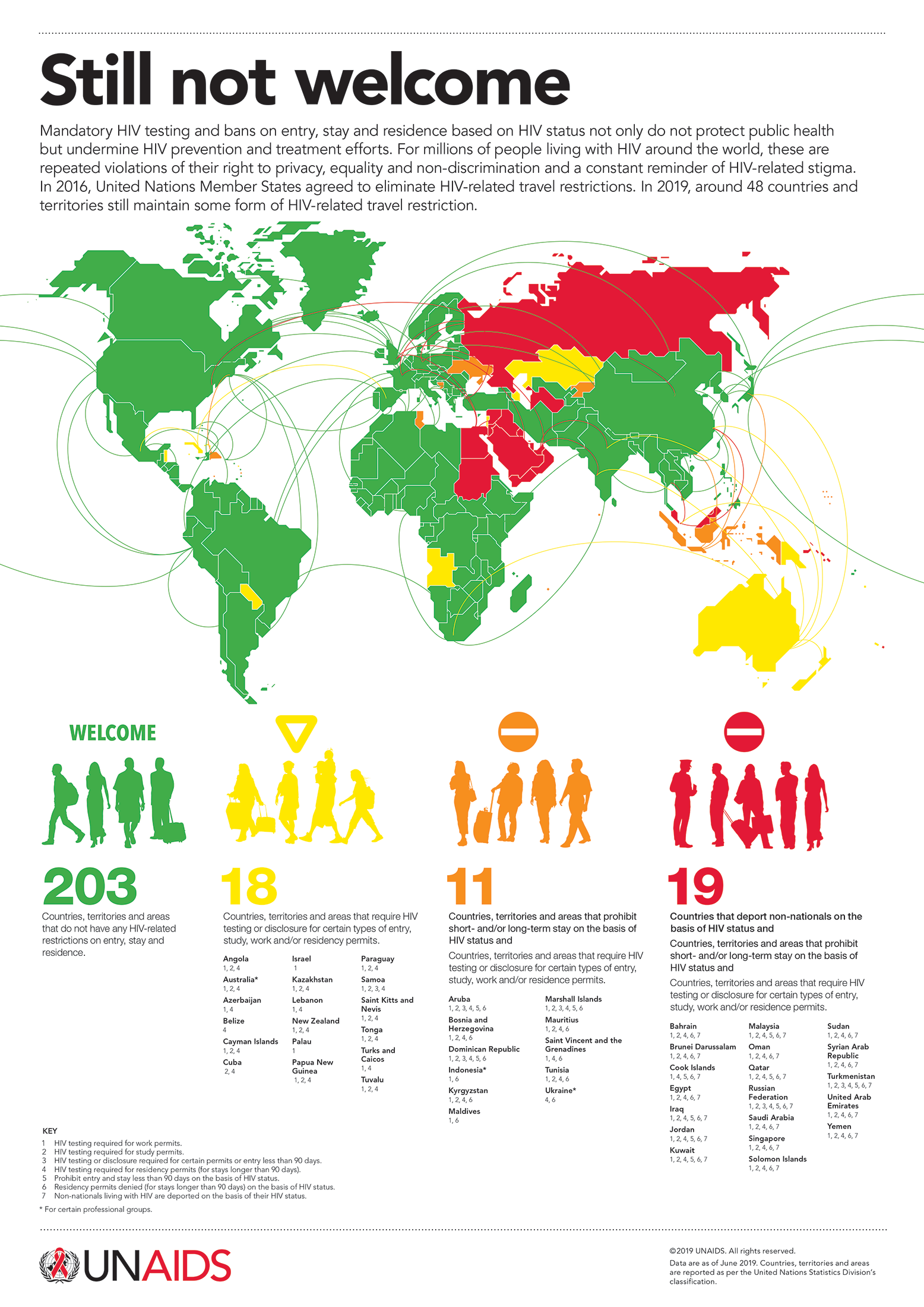

In 2019, 48 countries and territories impose some form of HIV-related restrictions and mandatory HIV testing that prevent people living with HIV from legally entering, transiting through or studying, working or residing in a country, solely based on their HIV status.

Mehdi Beji (not his real name) couldn’t wait to start his new job in a North Africa Middle East country. He had packed his belongings and said his goodbyes in Tunisia and filed all the paperwork requested by his new employer. Before his contract was approved, he had submitted the results of the blood tests he had been asked to take, but after he started work he was requested to get his blood tested again.

“After a month, I was contacted for an appointment to get my credit card, and when I arrived at the mall, I was arrested by the police,” Mr Beji said. At the police station he was informed he was HIV-positive and that the country’s laws deny residency to people living with HIV.

"They deported me back to Tunisia without money and I was not able to recover my two months salary,” Mr Beji said. “When I contacted the bank, they informed me that the only way to access my account was through the bank card that they refused to grant me.”

Treated like a criminal

For 12 years Karim Haddad (not his real name) lived and worked in a North Africa Middle East country. As part of his medical check-up for his residency permit, his blood was tested for HIV without his consent. On the day he went to collect the test results, he said, police officers handcuffed him and locked him in a room.

Four days later, the authorities informed him that his deportation was imminent because of his HIV status. “I didn’t know anything about the virus, so I asked what HIV is and got no answer,” Mr Haddad said. He recalled feeling paralysed with fear.

When he asked about his wife and children, he was told that they would all board the same flight and would meet him at the airport. As for his financial rights or his belongings, he said they just kept repeating, “You have no rights.”

“I left the country as if I were a criminal,” Mr Haddad said, still in disbelief.

Nightmare

The above tales are experiences that Amina Zidane (not her real name) knows all too well. She left Algeria at the age of 19 for work. After a few years, her annual medical check-up did not go as usual.

“I could hear the nurses whispering to each other, “This is the one.”” She suspected something was wrong, so she asked her sister, who had accompanied her to the clinic, to get her results. “My sister told me that the police were downstairs saying that they had come “to arrest a woman with AIDS,”” she said.

She recalled being taken to jail and prayed that there had been a mistake or that it was just a bad dream. “They did not open the door, they just sent me food through a small window," Ms Zidane said.

A week later, the authorities deported her. “I was left at the border with my passport and my son,” she said. Her husband escaped because he didn’t want to be deported. “Fourteen years of my life disappeared just like that and I had done nothing wrong.”

Lost son

Sabrina Abdallah (not her real name) lived in a North Africa Middle East country most of her childhood. After passing a computer science degree, she married a fellow Sudanese. They rejoiced when they had a baby boy.

At barely three months old, their son’s cold would not clear up. Despite being in a hospital, his condition didn’t improve. “It's really hard to see one’s child suffering and feeling so helpless,” she said. At first, her doctor thought that her son might have cancer, but he was eventually tested and found to be living with HIV. “While I was in the midst of my anxiety and fear, news spread at the hospital about my son, and they placed him alone in a room, with no one looking after him,” she said.

Ms Abdallah tested for HIV and found out that she was also living with HIV. “They asked me to take my son and go home,” she said. “They wouldn’t let us leave him at the hospital and even assigned a police officer to escort us and make sure we would not leave the baby behind.”

Child in hand, she tried to get some answers. That’s when her husband told her he had known his HIV-positive status all along. She couldn’t understand why he would hide something like that from her. The police took her husband to jail and 10 days later they were all deported to the Sudan. She started treatment but unfortunately it was too late for her son.

She eventually divorced her husband because, she said, she could never forgive him for the death of their son.

Student uprooted

For two years, Miriam Pepple (not her real name) studied at a university in central Europe. She paid her tuition fees and adapted to student life far from home. When she started having abdominal pains, she went to the student clinic. They advised her to have surgery. She had blood tests done, but thought nothing of it, since she had submitted her clinical tests to get a student permit while in her home country, Nigeria.

She said that the university asked her to take more blood tests and to bring her passport. After being told to visit various offices at the Ministry of Health, she was told to report to a police station. A day later, the authorities handed her an airline ticket to Abuja, Nigeria, along with a letter from the immigration office that claimed that she was an inadmissible immigrant.

What shocked her even more, she said, is the letter she received from her university. “They said that I had terminated my studies on my own accord,” Ms Pepple recalls.

“I lost my self-esteem, dignity and respect,” she said. Her hope is that no one should ever go through such treatment because of the huge social and psychological affect it had on her.

Life crushed

Pradeep Agarwal (not his real name) was a successful businessman, working throughout the Middle East. He worked in three Gulf countries for more than 10 years until his life came crashing down around him.

“In a matter of hours, I lost my job, my dignity and my home,” Mr Agarwal said. “I was informed I was HIV-positive and had to leave the country.” He recounts being escorted by the police to a quarantine room. “After being treated for years with respect and dignity, I found myself with other people from all nationalities, among them doctors and engineers, treated in the same inhuman way,” he said.

“I was not even given a medical report that could enlighten me and I was spoken to in Arabic, which I do not understand,” he said. “I suddenly had become a criminal in their eyes.”

After his return to India, he became depressed and has been unable to find another job. He believes that deporting people who are living with HIV gives governments a false assurance that their societies are safe. “In fact, these travel restrictions and expulsions drive people underground, so it makes the situation worse,” Mr Agarwal said. “I want people to be more aware of these violations,” he added. “I want them to stop, so others do not suffer the same horrible fate I suffered.”

UNAIDS believes that these laws discriminate, impact on human rights and have no public health justification.

“For many of the millions of people living with HIV around the world, travel restrictions are a daily reminder that discrimination continues to be entrenched in harmful policies,” said Luisa Cabal, UNAIDS Director, a.i., of the Community Support, Social Justice and Inclusion Department. “They deny people’s freedom and, even worse, force people to abandon their workplace, school and home.”