Update

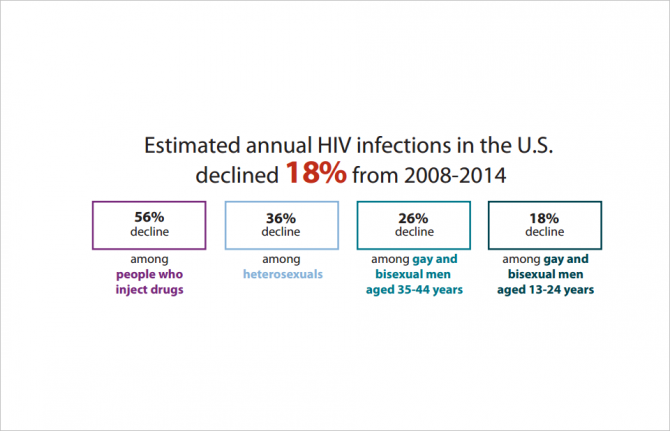

New HIV infections down by 18% in the United States of America

16 February 2017

16 February 2017 16 February 2017The state of Georgia, the home to the Ponce de Leon Center in Atlanta, saw a 6% annual decline in new HIV infections between 2008 and 2014. The clinic treats more than 6000 people living with HIV. Marianne Swanson, a nurse at the clinic who is also living with HIV, told UNAIDS about the antiretroviral therapy that she and her clients take to stay healthy and to ensure that their loved ones stay HIV-free. Treatment for HIV is playing a major role in HIV prevention. New evidence released shows that annual new HIV infections in the United States of America fell by 18% between 2008 and 2014, but that not all groups are benefitting equally.

Nurse Marianne Swanson uses own experience of living w/#HIV to ensure best care for patients https://t.co/rQ0TB8SQVi via @atlantamagazine pic.twitter.com/aUjW9dTj4B

— Michel Sidibé (@MichelSidibe) February 8, 2017

The estimates were released by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, taking place in Seattle, United States of America, from 13 to 16 February.

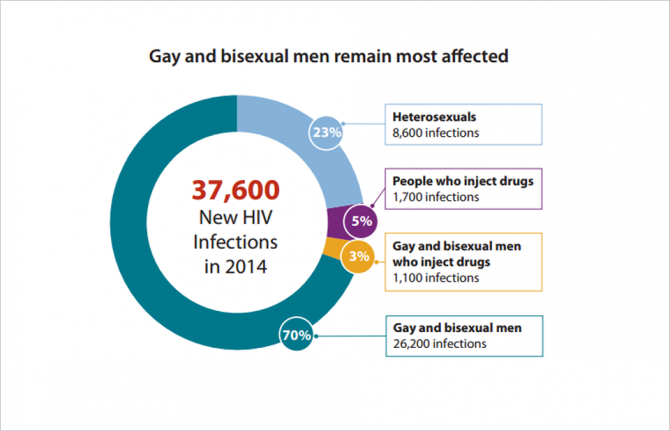

The CDC’s estimates show that while the number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs fell by 56% from 2008 to 2014, there was no decline among men who have sex with men in the same period. The number of white and young men who have sex with men acquiring HIV dropped in the six-year timespan, but increases among other groups—most notably 25- to 34-year-old men who have sex with men, with a 35% increase—were responsible for the general flatlining of new infections among men who have sex with men in the country.

The drop in new HIV infections also varied by location, with states and districts showing drops of up to 10% annually, for example Washington, DC, while others experienced lower declines—for example Texas, with a 2% annual drop—or remained stable. No states showed increases in new HIV infections, however.

The CDC attributes the 18% decline from 2008 to 2014 in large part to the increased number of people living with HIV knowing their HIV status, accessing treatment and becoming virally suppressed—including the clients of the Ponce Center—as well as the success of past programmes for people who inject drugs and the increasing use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). This shows the importance of the Fast-Track approach and its 90–90–90 targets for 2020 towards ending AIDS by 2030, whereby 90% of people living with HIV know their HIV status, 90% of people who know their HIV-positive status are accessing treatment and 90% of people on treatment have suppressed viral loads.

While the 18% reduction in new infections between 2008 and 2014 is very encouraging, additional tailored programmes are needed to achieve a 75% reduction by 2020, as set out in the 2016 Political Declaration on Ending AIDS.

The variance in the decline in new HIV infections among different groups of people and in different states shows the importance of a location and population approach, in which programmes are focused on the people and places that will deliver the greatest impact. CDC’s High-Impact Prevention approach plans to scale-up prevention programmes through such a location and population response.

By scaling up prevention programmes and ensuring that more people stay HIV-free, the hope is that the need of clinics like the Ponce Center, and the thousands like it worldwide, to provide HIV treatment to people living with HIV will be much less in the future.

Resources

Region/country

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025