THA

Feature Story

Can this innovation change the way people think about HIV?

16 October 2024

16 October 2024 16 October 2024In 2020, a gay Thai man living with HIV sparked controversy with a Facebook post. He was on antiretroviral therapy and had gotten lab tests to check the level of virus in his blood. Since his viral load was undetectable, he wrote, he was going to stop using condoms.

The public responded with a mix of contempt and disbelief. How could he? So selfish! So reckless! The resulting debate spilled from social media onto national radio and TV.

“There was a huge backlash,” remembered Dr Nittaya Phanuphak, the Executive Director of the Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI). She was telling the story from IHRI’s sunlit offices to teams from Botswana, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia. They’d come to Bangkok as part of a learning exchange coordinated by the Global Partnership for Action to Eliminate all Forms of HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination.

Dr Nittaya said that she and her father, Professor Praphan Phanuphak, thought it was their duty to contribute to the public discourse. While the man’s approach might have been unconventional, the science behind his statement was sound.

They would know. Professor Praphan diagnosed Thailand’s first HIV case in 1985 and dedicated his life to HIV research, service delivery and advocacy. He co-founded the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre which in 2014 conducted cutting-edge research as part of the Opposites Attract Study. Done in Australia, Brazil and Thailand, that study tracked couples in which one person was HIV-negative and the other was living with HIV but had achieved an undetectable viral load through successful HIV treatment. It confirmed that after two years of unprotected sex, there were no cases of HIV transmission between more than 300 couples.

“It’s a scientific fact,” Dr Nittaya said. “For me, I felt like we really needed to do something. We cannot just wait 50 years for this knowledge to gradually seep into Thai society.”

The “knowledge” to which she refers is the concept of undetectable = untransmittable, or U=U for short. Last year the World Health Organization further endorsed the principle, stressing that when a person’s viral load is undetectable there is zero chance of sexual transmission.

“Before, HIV treatment just meant longevity,” said Pan (not his real name), a person living with HIV. “But with U=U, now it is love without fear.”

Within three to six months a person who takes their HIV treatment as prescribed and receives viral load monitoring can confirm that they have achieved an undetectable viral load. This removes the self-stigma associated with having an “infectious” disease. For Thai HIV response stakeholders, this concept can also transform the public’s attitudes about people living with HIV, making it easier for them to live full, happy lives.

“If social perceptions can be brought in line with the reality of HIV treatment, we can remove the stigma around getting an HIV test or diagnosis,” said Eamonn Murphy, Regional Director of UNAIDS Asia Pacific and Eastern Europe Central Asia. “The more supportive the society, the more people we successfully treat and the fewer new infections.”

But for the U=U strategy to be fully utilized, work must be done to dispel myths and bolster confidence in science.

According to UNAIDS Country Director for Thailand, Dr Patchara Benjarattanaporn, a key step in the national process was bringing decision-makers together with relevant stakeholders, including voices from communities.

“They considered both global and local evidence,” she explained. “Now there is consensus about the science. U=U also conveys the message ‘you=you’, affirming that all individuals are equal and that people are more than their HIV status. It emphasizes the importance of ensuring people are fully informed about their options and respecting their right to make choices about their sexual health depending on their realities.”

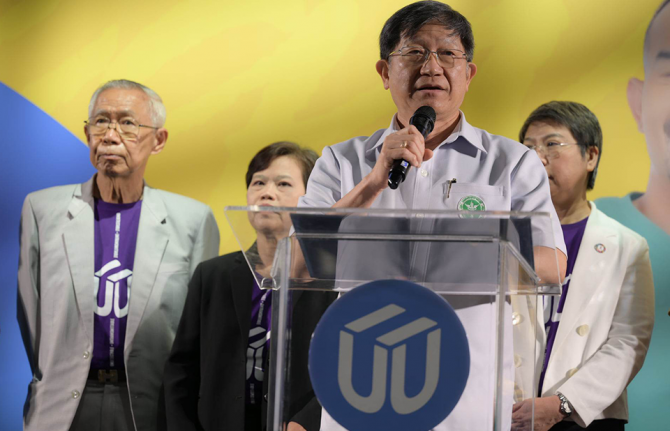

At the opening ceremony of the eight-country learning exchange, Dr Niti Haetanurak, Department of Disease Control Deputy Director, noted that the U=U concept is a key element of Thailand’s “all of society” strategy to address the prejudice and rights violations people living with HIV face. Thailand has a National Costed Action Plan to Eliminate all forms of HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination. The Ministry of Public Health and Sub-National Committee on AIDS Rights Promotion and Protection under National AIDS Committee coordinate the effort. Community organizations play a leading role.

During the exchange the country teams visited the Service Workers in Group (SWING) Foundation which serves sex workers and IHRI’s Tangerine Clinic which primarily serves transgender people. Both have come up with innovative approaches to ensure groups that usually find it challenging to receive healthcare at state-run facilities can get HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment in a friendly environment.

A key strategy is training members of those very communities to provide certain services themselves. They can even start clients on treatment for HIV and some other conditions the same day they are diagnosed. This approach makes it less likely for people to disappear into the shadows after diagnosis, with a high chance of infecting others and eventually becoming ill.

“This community-led health model can be applied to any health condition or population. But this does not really address stigma and discrimination. It just bypasses it by opening up alternative service delivery outlets for people who want to avoid negative experiences elsewhere,” Dr. Nittaya said. “We need to address the heart of the stigma as well. That is why we are working on using U=U as a tool to explore how we can shift attitudes.”

The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) is integrating this concept into its work in healthcare settings and the workplace. A masterplan is in the works. One branch of the strategy will tackle employers requiring HIV testing in the pre-employment phase or targeting employees they find out are living with HIV. Another aspect of the approach is the integration U=U into all levels of HIV service delivery and ongoing healthcare worker sensitization. All staff in clinics and hospitals are trained, not just nurses and doctors.

The work doesn’t stop there, though. Describing the Bangkok society as “open”, Dr Tavida Kamolvej, Deputy Governor of Bangkok, said that the whole of society was ready for deeper conversations about inclusion and HIV. But how could these approaches be applied in other countries and cities that are not quite as tolerant or accepting, she was asked.

“If you are confronted with beliefs that might not allow open conversations about HIV, sexuality and sex, you can strategically make it about health literacy, dignity and care for all people. I think this is soft enough to make people aware about health and wellbeing,” Dr Tavida advised.

Click here to learn more about the recent eight-country learning exchange to eliminate all forms of HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Documents

Expanding the HIV response to drive broad-based health gains: Six country case studies

15 April 2024

As progress lags in achieving most of the health targets of United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3), efforts to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 stand out as a beacon of hope. Since 2010, annual new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths have declined globally by 38% and 51%, respectively. Although the world as a whole is not currently on track to reach all the SDG targets, evidence clearly indicates that ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 is achievable and that clear pathways exist to reach this goal.

Related

Comprehensive update on HIV programmes in South Africa

Comprehensive update on HIV programmes in South Africa

25 February 2025

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

19 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

Feature Story

South-to-south — Indonesia and Thailand exchange learning on responding to HIV

15 September 2023

15 September 2023 15 September 2023Thailand’s HIV response can provide important learning for other Southeast Asian countries, with the experience of having already reached 90-90-97 in the treatment cascade in 2022, on the way to the achieving the “triple 95s”. The country was first in the region to eliminate mother-to-child HIV transmission. AIDS-related deaths have declined by 65% since 2010. With support from Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), UNAIDS helped organise for Thailand to share lessons it has learned in its HIV response with Indonesia through a south-to-south learning exchange mission of Indonesian delegates to Thailand.

On day one, the Indonesian Ministry of Health and Thai Ministry of Public Health delegates discussed the HIV epidemic, trends, and challenges in each country. They shared insights on HIV prevention, treatment and stigma reduction in the HIV response. The following day, the mission team visited community organisations— including the Service Worker in Group Foundation (SWING), a non-governmental organization working for sex worker rights, and the Rainbow Sky Association of Thailand (RSAT), an organization that offers sexual healthcare for men who have sex with men, migrants, people who use drugs, sex workers and transgender people.

Multidisciplinary care is provided in Thailand to people living with HIV and to key populations through community service providers, incorporating certified community counsellors, medical technicians and caseworkers at the community facilities, and through doctors, nurses, pharmacists and laboratory scientists through the telehealth system.

Indonesia’s delegates on the visit highlighted that they had found helpful areas to improve community engagement in their national HIV programme, with a focus on effectively addressing the barriers and limitations in the HIV response that are interlaced with stigma and discrimination across Indonesia.

“We learned how Thailand prioritised zero discrimination, one of which is developing an e-learning curriculum for healthcare workers to minimise stigma and discrimination in healthcare facilities,” said Dr Endang Lukitosari, who heads the National AIDS Programme of Indonesia’s Ministry of Health.

Thailand’s delegates shared experiences from their community complaint support and crisis response system. Health workers, communities and clients can use QR codes at various locations to report rights violations, promoting accountability and coordination between health facilities and community organisations.

The Ministry of Public Health of Thailand noted that community workers are actively involved in the HIV response throughout a robust system of accreditation for both individual community health workers and community organisations. There are health insurance options for all users, including three that can be accessed by migrants. These initiatives help create an enabling environment, led by the government, to connect communities with marginalised groups and tackle issues such as loss to follow-up.

Indonesia’s delegates noted the significance of community mobilisation in the HIV response and envisaged that by putting community in the centre they would reach the most marginalised and underserved groups across different islands and highlands in Indonesia.

“Thailand's comprehensive service delivery inspired me, especially through the Ministry of Public Health's accreditation and certification system for communities. This cooperative mechanism across the government and community stakeholders is the one we haven’t sufficiently addressed in Indonesia. Perhaps by applying this approach, we can minimise the gaps in the treatment cascade by ensuring we leave no one behind”, said Irfani from GWL-INA, Indonesia’s network of men who have sex with men and transgender people.

Over the five days, Indonesian delegates explored public HIV service centres and treatment facilities in Bangkok, Thailand and learned about how efforts of communities and government in HIV prevention and control could be streamlined and coordinated by enhancing the continuum of care and minimising loss to follow up. Notably, Thailand emphasised integrated, One-Stop, services as pivotal for a successful HIV response. Indonesia’s delegates sought a pathway for sustainability in the HIV programme through lessons from the continuity of HIV treatment services in Bangkok, which connects clients with community clinics and public health facilities through referral system and telehealth.

Delegates agreed that this learning mission highlighted key features in efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination, mobilise communities in HIV response, and improve access to quality healthcare by tackling barriers. In addition, the mission underscored efforts to support the delivery of client-centred services for key populations. The debriefing concluded with a commitment to continue the technical partnership on HIV between the two countries.

"I believe Indonesia can do it," said Krittayawan Boonto, UNAIDS Country Director of Indonesia. "Indonesia is in a similar situation to the one Thailand faced a few years ago. Thailand's strategies contributed to getting closer to their goals. I see potential in Indonesia to accelerate progress towards triple 95s. I hope these learnings from Thailand mission can advance the HIV response in Indonesia. UNAIDS Indonesia will keep supporting efforts to end AIDS by 2030."

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

How to build stigma-free key population services

23 June 2023

23 June 2023 23 June 2023At his previous factory job, Tom Wang (not his real name) says coworkers gossiped about his sexuality and made fun of him. When he visited a public health facility for an HIV test, the nurse peppered him with questions like “Why do you need it? Have you been sleeping with many partners?”

Thailand is a country famed for its tolerance. It is among the world’s top locations for gender affirming care. Same-sex sexual activity hasn’t been criminalised since 1956. And the policy tide is turning on other key population issues. A 2021 Drug Law allows for harm reduction as opposed to automatic imprisonment, while a bill is in the pipeline to affirm the rights of sex workers. Yet stigma and discrimination persist. In homes, communities, schools, workplaces and—critically—healthcare settings, discriminatory attitudes can take their toll.

“Microaggressions—intentional or unconscious verbal or behavioural slights toward stigmatised groups—can drive people away from HIV prevention and treatment,” noted UNAIDS Regional Human Rights and Law Adviser, Quinten Lataire. “There are evidence-based approaches for measuring and lowering both overt and subtle stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings.”

It was this need for stigma-free services that led to the establishment of the Rainbow Sky Association of Thailand (RSAT). RSAT offers sexual healthcare for men who have sex with men, migrants, people who use drugs, sex workers and transgender people. It also advocates for the full rights and equity of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) communities. Tom Wang is amongst the clients who have benefited from their support.

This work is critical if HIV programmes are to reach and retain key population communities. In Thailand, as in the rest of Asia, these groups carry the heaviest HIV burden. Nationally HIV prevalence is 1% for sex workers, 8% for people who use drugs, 11% for transgender women and 12% for men who have sex with men.

A one stop shop for sexual health services

RSAT’s approach demonstrates how programmes can improve outcomes by implementing strategies to affirm and empower clients. They are jointly supported by PEPFAR, USAID, EpiC, the National Health Security Office (NHSO) and Thailand’s Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI).

There are no depressing charts or drab walls at their five key population clinics. At the Bangkok site the rainbow motif appears on the floors and walls. There are swarms of cut-out butterflies. Signs are either upbeat and multi-coloured or a soothing blue.

Most of the staff are themselves members of key population groups. All staff receive anti-stigma and discrimination training which even addresses the fine point of body language. Nothing about staff’s interactions should make a client feel judged or uncomfortable. The entire team is retrained annually. There is an internal complaint mechanism that allows clients to confidentially flag issues, as well quality assurance staff to ensure Standard Operating Procedures are followed. Every team member signs a confidentiality agreement.

RSAT’s service package includes on-site testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, Hepatitis C, Tuberculosis and Covid-19. For transgender clients they offer hormone level monitoring. Mental health screenings which evaluate for depression, anxiety and stress have been integrated into the HIV service package. Where required, clients are referred for additional mental healthcare.

“Many of our clients engage in chem sex (recreational drug-use during intercourse). Some clients inject meth so we need to provide more than condoms. They also need clean syringes and needles which are part of our harm reduction package,” said Deputy Director, Kao Kierati Panpet.

Pre- and post-test counselling are critical. All counsellors are certified and accredited by the Ministry of Public Health according to Counsellor Supervisor, Sasiprapha Khamthi. Even before receiving HIV test results, clients know that treatment is available. Following a positive test, the counsellors reassure clients that with treatment they can live a normal life, explained Niphon Raina, Care and Counselling Supervisor.

“We also ask what their concerns are and give basic information about how HIV is and is not transmitted, using a picture book so they are clear on the facts,” Care and Counseling Officer, Bussarin Poonvisitkun added.

RSAT keeps a stock of antiretroviral therapy drugs onsite and can initiate new clients’ treatment on the day of diagnosis by giving them one month’s supply. Although HIV care is provided at the Ratchaphiphat Hospital, RSAT is able to dispense right away in accordance with instructions from a hospital doctor, delivered via telemedicine. Clients living with HIV receive help from the care and support team to navigate their next steps, including attending hospital visits.

RSAT also provides pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP services with hospital supervision. Mr. Tom Wang explains how this has protected his health: “I decided to get on PrEP because I am changing partners. To me PrEP is another means of protection in case you are intoxicated or the condom breaks. It’s a way to ensure I stay HIV-free.”

A redress mechanism for rights violations

The organisation advocates for structural changes to eliminate stigma and discrimination. For example, they are currently making recommendations for the Gender Recognition Draft Bill.

“But the reality is that policy and legal changes take a lot of time,” said RSAT Director, Tanachai Chaisalee.

While this longer-term work proceeds, a redress mechanism helps clients address current concerns. RSAT is tapped into the Crisis Response System (CRS) initiated by the Ministry of Public Health in collaboration with the Office of the Attorney General, Ministry of Justice. People with complaints about prejudice or rights violations in any sphere can scan a QR code and report their experience. Reports may also be sent via Facebook, email or LINE, Thailand’s answer to WhatsApp. A multi-disciplinary team conducts investigations and works with the client and other stakeholders to help.

The lion’s share of reports made via RSAT come from transwomen (78%) while gay men have lodged 17% of reports. The most common challenges relate to requirements for gender confirming attire, social exclusion (particularly during job application processes) and HIV status.

RSAT’s Human Rights Manger, Watcharawit Waraphattharanon, shares that they have been able to resolve some cases very quickly. For instance, if a person living with HIV is being forced to take an HIV test as a requirement for work, the Attorney General’s office does an emergency intervention.

“We can close these cases within one week,” he said.

“The work of key population-led, community-based organisations like RSAT is critical to reach those who most need HIV services,” UNAIDS Country Director, Patchara Benjarattanaporn stressed. “The Government’s progress in funding Community-led Health Services and building partnerships between these organisations and the public health system puts us on the path to end AIDS.”

A group of journalists visited the Ozone Foundation as part of the UNAIDS, UNDP, APN Plus and USAID/PEPFAR Southeast Asia Regional Workshop on HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination in Bangkok, Thailand on June 8, 2023. Learn more about this novel training

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Compassionate care for people who use drugs in Thailand

26 June 2023

26 June 2023 26 June 2023At the Ozone Foundation clients talk about their drug use with as much openness as they discuss their jobs or families. In the yard of their Bangkok drop-in centre we sit under the cannon ball tree. Prapat Sukkeang shares his story first.

He is the Chair of the Thai Network of People who use Drugs (ThaiNPUD). He’s used substances of some kind for more than three decades. He says he started because of “small problems”. Once his family found out, he was immediately alienated: “the community and society around me became distant,” he remembers. Mr Prapat still uses. He might have yaba—a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine—once a month.

“Ozone is the place I get knowledge about my health and about drug use. They give you information for your safety. I think without Ozone I might have overdosed,” he says plainly. “I feel very good to come here with service providers who see us as friends and provide healthcare services according to our needs. I feel respected. When we go to other places we always feel like criminals. If we go to a hospital they serve us last or reject us to get treatment. The service that we get is not equal to others.”

Jamon Aupama, a motorcycle taxi driver, lives with his wife in Bangkok. He goes to a state-run methadone clinic to avoid heroin withdrawal. He wishes he could take the methadone home and didn’t have to go there every day.

The experience at Ozone is different. Here the service delivery more closely matches his needs. He relies on Ozone for tests, clean equipment and “to hang out with friends”. He also goes for information.

“They give me detailed advice on how to protect myself from illness,” he says. “Some Ozone staff know personally about drug use, some do not. The trust comes from knowing them and the way they are trained,” Mr Jamon says.

From the ‘war on drugs’ to a more humane drug law

This people-centred service—and even these honestly told stories—were unimaginable just two decades ago. During the first three months of Thailand’s 2003 “war on drugs”, police killed almost three thousand people. Human rights groups reported widespread arbitrary arrests, beatings, forced confessions and compulsory detentions for “rehabilitation”. Use of HIV services by people who use drugs declined sharply. Terrified, people shrank into the shadows.

This chaotic context was the spark for Ozone’s formation. Back then they set up their first drop-in centres as safe spaces where clients could take a shower, have a meal and share their experiences.

Today the political and social climate is far different. A new Narcotics Law introduced in December 2021 provides for differentiated sentencing on drug crimes and alternatives to imprisonment for some offences. For the first time, the health and wellbeing of people who use drugs are being considered. There are provisions for harm reduction although it isn’t precisely defined. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) notes the continued existence in Thailand of compulsory treatment centres, deemed by the United Nations to be ineffective and a violation of human rights. Still, this more humane drug law is a first in Southeast Asia.

“Community-based treatment should be the way to provide care. Through community literacy we can understand the patient and the situation they face to get them to have a good outcome,” says Dr Phattarapol Jungsomjatepaisal, Director of the Department of Health Service Support at the Public Health Ministry.

Ozone’s holistic service package

Ozone Foundation’s Director, Verapun “Noy” Ngammee, explains that the organisation’s raison d'être is to respond to clients’ unique situations.

“They have bad experiences with stigma and discrimination,” he starts. “It’s difficult to trust people. Many of them have been suffering for a long time. We need to have peer organisations that are community-led and driven or you would not get clients coming to services. We respect the human dignity of all people. And we believe that safety is available to people before, during or after drug-use.”

Their model identifies each person’s specific risks and needs. They’ve found that much of the harm clients experience is not directly due to drug use, but rather to the environment—anything from the inability to access healthcare to harassment by police. Ozone employs a holistic approach that puts the client at the centre. One person might only require harm reduction counselling and tools while another is ready for support to quit.

The organisation collaborated with C-FREE, a laboratory service, for screening and monitoring of Hepatitis B and C, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They also offer the Hepatitis B vaccine. Research nurse Kewalin Kulprayong says her team has a welcoming approach.

“Clients know it is not a hospital,” she says. “It is safe. They can speak about everything here, drugs also.”

A doctor is available once a week. Some conditions can be treated at Ozone. In other cases, clients are referred to government facilities but with the benefit of peer support. These services are critical. An estimated eight per cent of people who inject drugs in Thailand are living with HIV while Hepatitis C prevalence is 42%.

"Universal Health Coverage in Thailand paves the way for comprehensive care, including essential services like HIV testing, pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP, treatment referrals, and screening and treatment for STIs and Hepatitis C. However, despite their inclusion in benefit packages, individuals who inject drugs face significant barriers due to pervasive stigma and discrimination, including self-stigma," says Patchara Benjarattanaporn, UNAIDS Country Director. “In this landscape, key population-led health services like Ozone’s emerge as invaluable one-stop shops, providing stigma-free care and ensuring that no one is left behind, especially those who use and inject drugs.”

Looking toward the future

Each Ozone client has their own dreams. One wants to run for political office. Another hopes to get his gender affirming surgery soon. A third imagines a life in the countryside with a small farm: “Not too many people,” he says with a chuckle. “Then I get in more trouble”.

He came to Ozone because he was depressed, anxious and dealing with a sexually transmitted infection.

“I did not have the confidence to go to a hospital and say, ‘I want treatment’. But I knew if I did nothing it would get worse. At Ozone they understand. They give me guidance. They’ve advised me to use social security to get mental healthcare. They tell me ‘people make mistakes sometimes’. I am one of those guys who makes many mistakes,” he confesses with another uneasy laugh. “But now the mistakes are getting less.”

A group of journalists visited the Ozone Foundation as part of the UNAIDS, UNDP, APN Plus and USAID/PEPFAR Southeast Asia Regional Workshop on HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination in Bangkok, Thailand on June 8, 2023. Learn more about this novel training.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

“Silence is better” — How the criminalisation of sex workers keeps exploitation in the shadows

28 February 2023

28 February 2023 28 February 2023As a girl Ikka dreamed of becoming an accountant. She knew her parents could not afford to send her to university, so she resolved to pay for university herself by moving into a brothel. For almost three years she lived and worked there while studying.

Davi’s parents divorced when he was a baby and he was raised by caring grandparents. In high school he led lots of extracurricular activities. He was also gay. Just three months before his final exams Davi was raped by a teacher who threatened to “out” him. He ran away to the city. After a desperate search for work, he landed a job in a massage parlour.

From the Bangkok offices of Youth LEAD and the Asia Pacific Network of People Living With HIV and AIDS (APN+), the pair reflects on those chaotic adolescent years with halting candour. They unpack layers of vulnerability and abuse—the way poverty and trauma can propel young people toward sexual exploitation, higher HIV risk and a cascade of rights violations. And they say that the criminalisation of sex work only made their situations worse.

“No one tells you anything other than that you need to please your client. Just be submissive and quiet. There’s no protection, no information, no nothing,” Ikka remembers.

The brothel would occasionally force the women to undergo HIV and STI testing. Saying ‘no’ wasn’t an option. But when Ikka went to a clinic on her own to get condoms or contraceptives, she was turned away.

Customers sometimes didn’t pay, became violent or refused to stop having sex after even two or three hours. Abusive clients routinely threatened to report them.

“If someone called the police, they would arrest the sex worker. The customer is king,” Davi says. “So silence is better.”

“The police wouldn’t take your report. They think they have more important cases than you,” Ikka adds.

UNAIDS Asia Pacific Human Rights and Law Adviser, Quinten Lataire, explained that criminal laws against sex workers make it very difficult for sex workers to demand basic rights, substantially increasing their risk for abuse and exploitation, such as from law enforcement officers.

“The criminalization of sex workers does not end sex work. It simply makes people go underground, putting them at higher risk of violence and HIV transmission. This has a devastating impact on the sex workers themselves, their clients and the society at large,” Mr Lataire said.

Almost all (99%) new HIV cases in young people in Asia Pacific are amongst key populations and their sexual partners. In Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Thailand, youth account for between 40% and 50% of new infections. Since 2010, HIV rates among young people have risen in Afghanistan, Fiji, Malaysia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Timor-Leste.

At ages 18 and 19 respectively, both Ikka and Davi learned that they were HIV positive. In Ikka’s case she was tested as a VISA requirement for a student exchange programme. Her results were forwarded to her school even before she got them and she was kicked out. From breach of confidentiality to discrimination in both education and healthcare settings—one rights violation after another. Ikka had the agency to confirm her HIV status at a community-based sex worker clinic she’d looked up and immediately started treatment.

Davi voluntarily tested with a community organization that visited the massage parlour to conduct sensitization sessions and offer services. He kept his status a secret at work but began attending support meetings on the weekend. He sometimes told the pimp that he was going out to meet a client, handing over the stipend he got from the organization when he got back.

“For eight months after I knew I was positive, I felt like I didn’t want to do sex work, but I needed the money. I told clients to use condoms but some of them would give me more money not to,” Ikka remembers.

The events that finally prompted her to leave the brothel still evoke strong emotions. Her best friend there also contracted HIV.

“I told her, ‘let’s go together to get antiretroviral treatment’. I showed her my medication as evidence. But she didn’t want to go. She would not get support from her parents and if the pimp found out, he would kick her out. She felt it was better to die,” Ikka remembers. Her friend passed away just two months after her diagnosis.

In both cases these young people demonstrated incredible resilience and were supported by community-led organizations with tailored services for sex workers and people living with HIV. Ikka joined an organization addressing sex workers’ rights, health and social support needs. She quickly carved a niche representing the interests and perspectives of young sex workers. She would go on to lead national young key population organizations and sit on the Global Fund’s Youth Council. Today she is the Regional Coordinator of Youth LEAD.

“I told myself I needed to help my community,” Davi says. “I don’t want no more people in my situation; no more students becoming victims of sexual violence; no more 19-year-olds HIV positive. I just chose to leave (the parlour) and volunteer with the community organization instead.” Encouraged and supported by community, Davi would go on to graduate from high school and earn a sociology degree. He is now aiming for a Masters qualification while working as APN+’s Youth Officer.

The issues Ikka and Davi faced remain today.

“I still use a condom, but many clients refuse,” says Rara, a 22-year-old sex worker. “When we’re desperate for money, we have no choice but to agree. In addition to gonorrhea, I got syphilis and got treated for it. Thankfully I’m still HIV negative.”

UNAIDS and the Inter-agency Task Team on Young Key Populations are working to address the inequalities faced by young key populations in Asia Pacific. Learn more about their work.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Thailand partners develop community-led HIV care curriculum

23 February 2023

23 February 2023 23 February 2023For 20 years Kochaphan Wangtan has been a community health worker, serving other people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Thailand.

“I’ve seen many friends living with HIV come to care very late with opportunistic infections,” she said.

“I focus on helping to bring them in and provide support to start antiretroviral treatment right away and I also conduct home visits, counselling and psychosocial screening so I can link them to services they need,” Ms Wangtan explained.

Ms Wangtan is from the Jai-Prasan-Jai Comprehensive Continuum of Care Center (CCC) from the Phan District Hospital in Chiang Rai province. She is one of almost one thousand PLHIV health workers who are embedded in more than 230 Thai hospitals and serve almost 60,000 PLHIV annually.

For the first time, the country has rolled out a national community health worker certification for these volunteers. The initiative is called “A Comprehensive Continuum of HIV/AIDS Care and Support for and by People living with HIV.” The curriculum was developed by the Ratchasuda College of the Mahidol University through close collaboration with the Thai Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (TNP+) as well as support from the Health Ministry’s Division of AIDS and STIs and the National Health Security Office. USAID-PEPFAR via the III Unify Collaboration Programme and UNAIDS provided technical and financial support.

“PLHIV volunteers have provided the first community engagement in the HIV response since the start of the epidemic in Thailand,” said UNAIDS Country Director, Patchara Benjarattanaporn. “Peer-led support boosts treatment initiation and retention and is central to the HIV response,” she said. This initiative ensures that PLHIV-led health services are standardized, recognized and valued.

Two modules are delivered over 90 hours. The first module focuses on theoretical training, including on holistic follow-up care, treatment adherence counselling and developing a comprehensive service plan. The second module is practical. Along with its HIV focus, the curriculum also integrates tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections, Hepatitis C and non-communicable diseases. Earlier in the month the first cohort of 46 PLHIV health workers received their certification.

Dr. Wachara Riewpaiboon, a rehabilitation physician and former Ratchasuda College Dean, developed the curriculum.

“The health system is not only for health professionals… It belongs to everyone,” she said. “Getting an HIV diagnosis does not help clients understand what they are facing. When people living with HIV tell their story, it is very different knowledge they are imparting. The knowledge that helps people make decisions for themselves usually comes from peers, not doctors.”

For her, care goes beyond medicine.

“It is not only biology that we are dealing with, but also psychology and our interaction with our social environment—how people look at people living with HIV and how they perceive themselves,” Dr Riewpaiboon continued. “It is very important to help people see the positive side of their experience.”

According to Nurse Chulaporn SingPae, an HIV Coordinator at the Phan District Hospital, PLHIV volunteers help with counselling, adherence, missed appointment follow-up, home visits, treatment deliveries, overcoming stigma including self-stigma and promoting understanding of U=U, undetectable equals untransmittable. (An undetectable viral load means the virus is not transmittable aka untransmittable.) The training ensures that these contributions are recognized by the health system as meeting quality standards.

Now that the course has been developed and tested, the curriculum has been recognized by the National Health Security Office (NHSO). Thai civil society organizations, who provide HIV and STI services with certified community health workers have been accredited and are eligible to register as health service units in the Universal Health Coverage scheme. Having supported the development and pilot of the curriculum, UNAIDS is now supporting a study to cost these services. The office is also working to promote sufficient and sustainable financing for community-led health services for PLHIV and key populations.

“This training is going to become the guarantee that a peer educator provides a high quality of service, in a holistic way, which encompasses not just the physical but also the mental, emotional and social aspects,” said Apiwat Kwangkeaw, Chairperson of the Thai Network of People living with HIV/AIDS. “As this becomes institutionalized, we are sending a message to the health system as a whole to let the community of peer educators be an equal partner,” he said. Mr Kwangkeaw hopes this will translate into sustainable domestic financing for community-led health services and better quality of life for PLHIV.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Preventing transmission and tackling stigma: The power of U=U

12 December 2022

12 December 2022 12 December 2022U=U, which stands for Undetectable = Untransmittable, is a vital public health message for the HIV response. Undetectable = Untransmittable means that people living with HIV who achieve an undetectable viral load through consistent antiretroviral treatment and monitoring cannot transmit HIV. As Thailand has shown, the message of U=U also helps in combatting the stigma which people living with HIV can face in healthcare settings and wider society.

U=U is a priority activity in Thailand’s 2017 – 2030 National Strategy to End AIDS. The approach has already been tested in the capital city, Bangkok. A same-day treatment initiation programme there has resulted in more than 95% of people on treatment achieving viral suppression after just six months of antiretroviral therapy. The national initiative brings together Thailand’s Institute for HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI), the Department of Disease Control, the Ministries of Public Health, Education and Labor, the National Health Security Office, and the Subcommittee on the Promotion and Protection of AIDS Rights, supported by UNAIDS.

Thailand’s wider HIV response has achieved strong results, with an estimated 94% of people living with HIV aware of their status, 91% of diagnosed people on treatment and 97% of those on treatment virally suppressed. But despite these successes, barriers remain as a result of stigma. There are too many late diagnoses, and some people remain fearful about accessing HIV services. To increase use of HIV services, to achieve U=U for all people living with HIV, it is vital to ensure that every person is treated with respect and dignity by the healthcare system.

Dr. Nittaya Phanuphak, Executive Director of the IHRI, emphasized that knowing one’s HIV status is the critical first step to enrolling in antiretroviral treatment.

“People at risk of contracting HIV and people living with HIV from all groups in Thailand must have equal and convenient access to HIV testing and, if positive, to antiretroviral treatment as soon as possible, which will lead to U=U,” said Deputy Minister of the Public Health Ministry, Dr. Sopon Makthon.

Thailand’s U=U initiative embraces a community-led approach which enables people living with HIV to support others who are newly diagnosed to start and stay on antiretroviral treatment. “Community leadership is vital to communicate U=U effectively,” said Patchara Benjarattanaporn, UNAIDS Country Director for Thailand. “This will help tackle stigma and self-stigma, and help boost positive health-seeking behavior.”

Apiwath Kwangkaew, president of the Thailand HIV/AIDS Network, urged all health workers to amplify the message of U=U: “Today's medical personnel must confidently explain U=U to enable social understanding. Health services must be brave and speak up. New understanding will bring change,” Mr. Kwangkaew said.

“UNAIDS welcomes amplification of the message that U=U. It is key to reaching the goal of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths,” concluded Taoufik Bakkali, UNAIDS’ Regional Director.

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Thailand’s Mplus: HIV services delivered in style

13 December 2022

13 December 2022 13 December 2022“This isn’t your mother’s clinic!” said one amazed visitor.

From banners to brochures, all promotional materials are slick and cheerful. Smiling faces and toned torsos are everywhere. A purple colour scheme covers the whole building. Even files and staff face masks are colour coordinated. A pair of Facebook Live hosts have the good looks and energy of K-pop stars. And the organization’s slogan is decidedly upbeat: “where community fulfills your happiness”.

Over almost two decades, Thailand’s Mplus Foundation has refined a unique approach to providing comprehensive HV services to key population clients including men who have sex with men and transgender women.

Their method goes far beyond a cool brand identity. Mplus has leveraged domestic and international partnerships to create a key population-led health service with impressive results. They dispense more than half of the PrEP in Thailand’s Chiang Mai province.

This year they tested 95% of the almost 8000 people they reached with face-to-face services. Of those who tested positive, 91% were placed on treatment while the other 9% are in follow-up case management. And 100% of their clients who received viral load testing were found to be virally suppressed.

“Community organizations can best reach key populations to receive services. We find that people who do not want to get tested at the hospital are comfortable with peers who they know understand their life,” explained Pongpeera Patpeerapong, Director of the Mplus Foundation.

Since its formation in 2003 Mplus has evolved to deliver a full range of services. They now have health centres in four provinces, while their mobile testing units serve clients in another five districts. They support a local hospital in each province, linking people to care and helping them with adherence. Mplus provides rapid testing, CD4 and viral load monitoring, and is also authorized to dispense medication. A small fleet of motorcycles even makes PrEP deliveries to clients in remote areas.

Both their online and offline engagements are anchored by a peer-led strategy. Their social media presence is commanding—everything from Twitter to Tik Tok. There are closed Facebook groups and special applications for clients to connect with community. Offline, they go beyond information booths to host parties and sport meet-ups. These aren’t just bonding exercises. Clients book appointments online and face-to-face interactions usually result in receiving an HIV test.

Mplus also provides technical assistance to other countries. It has supported an organization in Laos with online interventions and helped community groups in Cambodia develop campaigns to promote PrEP.

They played a key role in advocating nationally for the accreditation of community health workers. All Mplus staff are certified by the Department of Disease Control following a rigorous programme of study, evaluation and practice.

The programme continues to progress. Mplus is strengthening their mental and emotional health support offering, and is working towards becoming certified to provide HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment.

While in the past the programme was more heavily funded by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the United States Agency for International Development, today half of their investments come from branches of the National Health Security Office.

“Domestic funding is very important to develop our systems,” Mr. Patpeerapong said. “Community-based organizations have to be able to access domestic funding to cover more issues, including stigma and discrimination.”

Empowering key population-led health services has been crucial in improving Thailand’s HIV programme results. One of five people living with HIV in Thailand were identified and referred by a key population-led health service under the domestic health financing scheme. Four out of five people on PrEP in the country are served by community-led organizations. These services play a critical role in Thailand’s strategy of Reach, Recruit, Test, Treat, Prevent, Retain.

“Thailand is well-positioned to be a leader in addressing the need for a sustainable community-led response as a critical part of the health infrastructure,” said UNAIDS Country Director for Thailand, Patchara Benjarattanaporn. “By creating an enabling system for health outreach we can address the challenge of late diagnosis and better reach key population communities with services.”

Thailand has integrated HIV services into its Universal Health Coverage scheme and increased investments in key population- and community-led health services. UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) members visited Mplus and other community-led health services ahead of the 51st PCB meeting in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

The power of bringing together government and community HIV services

15 December 2022

15 December 2022 15 December 2022The Sanpatong Hospital in North Thailand has reinvented and refined its HIV programme for more than three decades. It began attending to people living with HIV in 1989, and in 1996 started offering antiretroviral treatment.

“We have patients who have been with us for 30 years,” says Dr Tawit Kaewprasert, Deputy Director of Provincial Public Health Office and Director of Sanpatong Hospital.

In the last five years the hospital has not had a single case of mother-to-child HIV transmission. An impressive 96% of people on treatment who received viral load tests there this year were virally suppressed, with 98% of those patients being undetectable. Management speaks about the 92% retention rate for clients who were on treatment in 2022 in terms of how those results can be improved.

“We have not achieved that target just yet,” Dr Manusin Kongka says, referring to the proportion of people who stayed on antiretroviral therapy. “But we can reach the target and even achieve beyond 95%.”

The team even aims to achieve 100% viral suppression among people who have been on treatment for at least five years. The current 96% result isn’t considered to be good enough.

This ambitious goal-setting flows from the National HIV Policy and Thailand’s commitment to end AIDS by 2030 through a well-articulated strategy to reach, recruit, test, treat and retain people in care, while also working to prevent new infections.

Of course the strategy relies heavily on Sanpatong and institutions like it. This 130-bed facility boasts a central lab that serves surrounding hospitals in Chiang Mai, Lamphun and Mae Hong Son with HIV diagnosis, CD4, viral load monitoring and some opportunistic infections testing.

Their approach includes the adoption of HIV response best practices including PrEP, index testing and same-day treatment initiation.

“Patients can start treatment before they even get their CD4 result,” Dr Kongka explained.

All staff have received anti-stigma training as well as orientation around the U=U, undetectable = untransmittable, initiative. The facility uses a differentiated approach for antiretroviral treatment delivery. Depending on their health status, some clients can collect multiple month dispensing at district health promoting hospitals while others can receive their medicine by mail.

But a major key to Sanpatong’s success is the linkages it has made with groups of community-led organizations to drive case detection, linkage to care, psychosocial support and the monitoring of services. The Hospital works with Mplus, CAREMAT and FHI360 on prevention, testing and retention in care. Organizations of people living with HIV run support groups. The Community Led Monitoring team even helps primary care nurses to contact patients who have been lost to follow up and conduct home visits. The people living with HIV network collaborated with key community-based organizations in Chiang Mai to conduct community-led monitoring to improve the quality of HIV services at the Sanpatong hospital.

“Our collaboration with community organizations increases awareness about HIV, improves quality of care and access to care, decreases the waiting in community clinics and increases continuity of care for HIV patients,” said Ms Sineenuch Suwansre, HIV Coordinator.

This close collaboration with communities is enhanced by the Thailand Government’s move to integrate HIV services into the Universal Health Coverage scheme. Now certified organizations and lay HIV service providers can access domestic financial support within the national health infrastructure.

“Universal Health Coverage is a mechanism for the sustainable financing of HIV prevention as well as sustainable financial support to key population- and community-led health services. The Thai government’s move to fund Community-led Health Services as an element of the mainstream public health system is a win for people living with HIV, for HIV prevention and for sustainability,” said UNAIDS Thailand Country Director, Patchara Benjarattanaporn.