Sex workers and clients

Feature Story

Lessons from the Ashodaya PrEP project in India

07 October 2020

07 October 2020 07 October 2020The Ashodaya pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demonstration project for female sex workers in south India has shown how PrEP and HIV prevention programmes can be strengthened and their implementation accelerated beyond pilot projects.

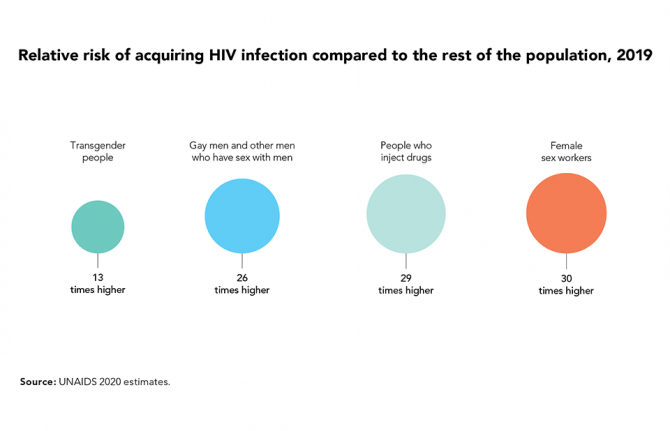

While PrEP has been shown to be highly efficacious, with nearly 100% protection if it is taken as directed, delivering a successful PrEP programme is challenging. HIV prevention efforts among sex workers have traditionally focused on condom use, and while a range of successful programmes have contributed towards the decline in new HIV infections in the Asia–Pacific region, sex workers still experience a disproportionate burden of infection. In 2019, 9% of the estimated 300 000 new HIV infections in the Asia–Pacific region were among sex workers and globally the relative risk of HIV infection is 30 times higher among sex workers than among the general population.

PrEP is a relatively recent addition to the range of HV prevention options available. It involves someone who is HIV-negative taking antiretroviral medicines prior to possible exposure to HIV. Although recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for all people at substantial risk of HIV since 2015, PrEP is inaccessible to the majority of key populations, including sex workers, and their partners in the Asia and the Pacific region. There is limited evidence on PrEP use among women, and particularly among female sex workers, in Asia and the Pacific.

The Ashodaya PrEP demonstration project was one of two community-led and community-owned initiatives to provide PrEP to female sex workers supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (the other was led by the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee Kolkata). Sex workers in India had been concerned by the fact that, although condom use was high, some sex workers still acquired HIV.

“Our project shows that community-led PrEP delivery can be effectively integrated into the existing HIV prevention and care services for sex workers and result in high retention and adherence. Policymakers need to consult with us, listen to us and trust us as we know what works for us and how to make it work. We have an obligation to make PrEP available as an additional prevention tool in a safe and sustainable way and we are advocating for that,” said Bhagya Lakshmi, Secretary of Ashodaya Samithi.

The PrEP demonstration project, which began in April 2016 and ended in January 2018, reported good results. High levels of continuation on PrEP were reported, with 99% of the 647 participants completing the 16 months of follow-up. For women, it is critical to take PrEP daily to maintain protection. Although adherence was only 70% at month three, this increased to 90% at month six and was 98% in the final month of the project. Self-reported adherence was verified in the blood of a subset of participants at months three and six.

The project not only helped to dispel some common fears about PrEP but showed benefits in bridging the prevention gap. Rather than undermining condom use, it remained stable. Condom use was high for occasional clients, at approximately 98%, but lower for repeat clients (87–96%) and regular partners (63%). There were also no increases in symptomatic sexually transmitted infections and no cases of HIV acquisition during the follow-up period.

Several factors contributed to the success of the Ashodaya PrEP project, including:

- Fully integrating PrEP into an existing range of health services, outreach and community mobilization. This approach recognized that PrEP is not just a medicine or a standalone service but is part of a prevention and health package, including sexual and reproductive health services.

- Communities leading the way: planning, implementation and monitoring.

- Preparing the community and ensuring ongoing engagement. An intensive process of community preparedness and ongoing engagement allowed sex workers to make informed decisions about participation.

- Addressing excluded groups early. Recognizing that many community members would miss out, the community was proactively informed that not all members would be eligible for PrEP under the demonstration project, given the limited places and scope.

- Prioritizing continued engagement over perfect adherence. Drawing on Ashodaya’s existing network of peer outreach workers allowed for individualized adherence support strategies to best meet the needs of PrEP users, both in terms of scaling up support when dips in adherence were observed and through referrals to Ashodaya’s comprehensive package of health and social services beyond PrEP.

“We cannot stop new HIV infections in Asia and the Pacific if we stick to business as usual,” said Eamonn Murphy, Director, UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia and the Pacific. “PrEP answers an unmet need and expands the prevention options for people at substantial risk of HIV. We need to scale up PrEP as an additional effective HIV prevention intervention. The principles of the Ashodaya PrEP demonstration project is a model not only for India but for the entire region. The lessons learned from the project are critical to informing the way forward in the prevention agenda.”

From conceptualization to planning, implementation and monitoring, the Ashodaya PrEP project was a community-led process. In 2018, the pilot project ended and analysis of the results was completed with support from UNAIDS India and WHO. Since then, Ashodaya has trained a cadre of community members as advocates for PrEP in partnership with the All India Network of Sex Workers and with support from AVAC. Ashodaya, with support from UNAIDS, WHO, the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee and the All India Network of Sex Workers, is also continuing to advocate for PrEP with the Indian National AIDS Control Organization (NACO). Ashodaya is also exploring opportunities for community social franchising and marketing of PrEP to further support access. NACO has developed a draft national PrEP policy and guidelines. The community is eagerly waiting for the resumption of PrEP services.

Region/country

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Update

New HIV infections increasingly among key populations

28 September 2020

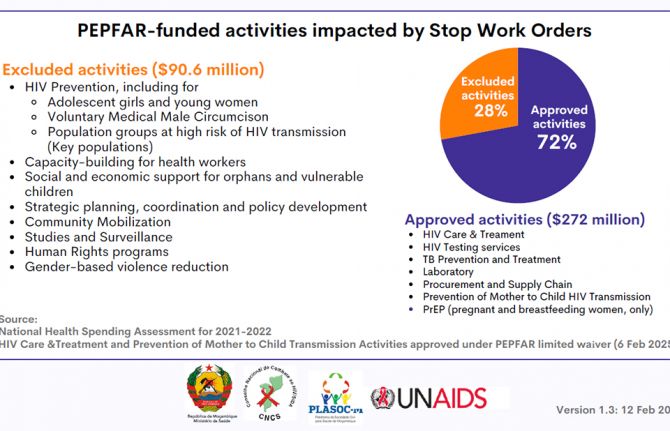

28 September 2020 28 September 2020In 2019, the proportion of new adult HIV infections globally among key populations and their sexual partners was 62%. This shift to an HIV epidemic increasingly among key populations is a result of the strong progress in HIV prevention in settings with high HIV prevalence in eastern and southern Africa, combined with a mixture of progress and setbacks in lower-prevalence regions.

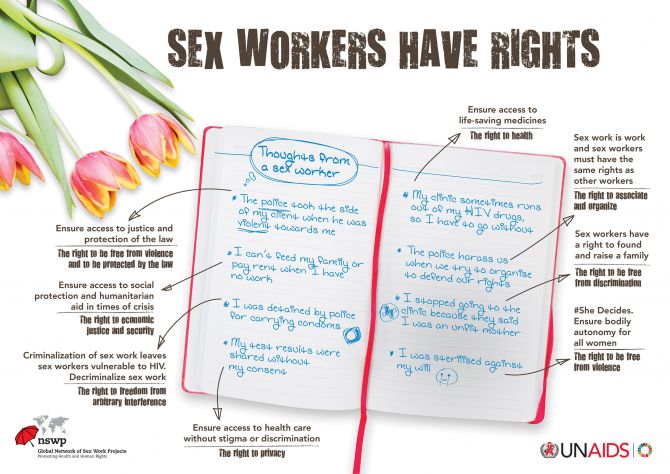

Key populations—which include sex workers, people who inject drugs, prisoners, transgender people, and gay men and other men who have sex with men—constitute small proportions of the general population, but they are at elevated risk of acquiring HIV infection, in part due to discrimination and social exclusion.

Learn more

Feature Story

Sex work during COVID-19 in Tanzania

25 August 2020

25 August 2020 25 August 2020“After COVID-19 kicked in, it has been too difficult to get customers,” says Teddy Francis John, a sex worker from Zanzibar. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, she has faced increased difficulties to earn an income to provide for herself and her two children.

“Everything has become tough and I had to start a small business of selling alcohol—local brew,” she says. The business also helps her meet new clients, as they come to her for drinks and are less vigilant about social distancing guidelines.

Ms John used to live and work in Zanzibar town, but to better earn an income and avoid paying rent, she decided to move to a more rural area. Here, she says, she can more easily find new customers for her local brew.

Rehema Peter is facing a similar situation, just on the other side of the ocean on Tanzania Mainland. She lives in the crowded suburb of Temeke in Dar es Salaam and works as a sex worker and volunteers as a peer counsellor for people living with HIV and for people who use drugs.

Her clients were regulars who used to come to her house, or she would visit those she could trust in their homes. But when COVID-19 broke out, they stopped coming.

“Coronavirus made life very hard. Payment at work used to be little and when COVID-19 came it reinforced the situation. On the side of my partners [clients], they stopped visiting and calling me. The very few who used to visit me often, I called them, but they said they have no money because of COVID-19, as some stopped going to their jobs,” says Ms Peter.

At her job as a peer counsellor she was offered fewer shifts, meaning a lower income. Because she is a former drug user, she has received some support through the Tanzania Network for People who Use Drugs (TaNPUD), which has been supported by UNAIDS to distribute food and hygiene items to people who currently use drugs and people in recovery.

“I just try to be calm and find other means [of income]. I’m searching for additional organizations that can help or support me anyhow. I also try to prepare soap and oil from the knowledge that TaNPUD gave me and I sell it,” says Ms Peter.

Continued services

Both Ms Peter and Ms John are living with HIV and are on HIV treatment. Due to the advocacy and assistance of UNAIDS and other partners of the Tanzanian government, disruptions to HIV services have been minimal in the country. This is felt by both women.

“During this time, it has become difficult to get services in government health facilities; unless you go to a private hospital where you must have cash. However, there is no problem at all in getting HIV-related services, including my treatment,” says Ms John.

Ms Peter say she can now get three months multi-month dispensing of antiretroviral treatment—even up to six months—since the healthcare staff do not want congestion in the clinics. This has helped both women in adhering to their treatment.

Increased stigma

Both Ms Peter and Ms John have experienced an in increase in the stigma and social exclusion they also face as sex workers and as women living with HIV during the COVID-19 outbreak.

“As some people know that I am living with HIV, they tease me. They say ‘prepare yourself for death. People like you never heal. You must prepare for your final journey’” recounts Ms Peter. She has faced discrimination in the community, but her family stands by her.

Ms John also faced increased gossip and mocking of her because of her work.

“People in my surrounding communities started mocking me and others. They gossiped as to how I would earn a living as there are not going to be customers because of the COVID-19 outbreak.” Says Francis John

Despite the COVID-19 outbreak being declared over in Tanzania and despite their continued efforts to find other means of livelihood, earning an income is still hard for the two women, due to continued social distancing regulations.

“[It] has been very difficult to provide this service and this harmed us economically. I know COVID-19 has affected the whole world but it has affected sex workers more because of the nature of our services; it involves proximity,” says Ms John.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

24 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

20 February 2025

Feature Story

Guyana community organization serves sex workers on the edge during COVID-19

29 July 2020

29 July 2020 29 July 2020The town of Corriverton in Guyana lies far east, on the Suriname border. Miriam Edwards, the Executive Director of the Guyana Sex Work Coalition, hired a taxi early last Thursday to take her team of peer counsellors there. They planned to conduct welfare checks, offer HIV testing and distribute care packages, masks and condoms as part of a project supported by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). It’s a nearly 200-mile trip from the capital, Georgetown. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the regular bus hasn’t been available. Other changes to the flow of life have been devastating for sex workers in Guyana.

“Because of the curfew they are not able to work. Plus the children are home full time. They (the sex workers) can’t make any moves. Some are able to look (work) for money, but in doing so they take more risk. Workshops are not their first priority,” Ms Edwards says plainly. “Their main need is food and sanitization.”

COVID-19 has meant fewer opportunities for work and more competition. A Dominican sex worker reported being attacked by a pair of local women. Her face was swollen and stitched when Ms Edwards got to Corriverton.

One Venezuelan woman ventured out during the curfew. She alleges that police officers in the border town detained her and demanded sex. When she refused, one of them hit her with his gun.

Another Venezuelan sex worker had gone missing since the previous weekend. Her documents and clothes were left in her hotel room, but she still hasn’t turned up.

The complications around sex work in Guyana have deepened since COVID-19. At a time when many locals are out of work, migrants have been particularly affected by joblessness. More of them are exchanging sex for money to survive.

According to a recent Response for Venezuelans (R4V) report by UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, there have been more reports of sex workers facing eviction or being at risk due to job loss.

“This situation increased their vulnerability of becoming victims of human trafficking, exploitation and gender-based violence,” the report says.

Meanwhile, many Guyanese sex workers have found it difficult to access the social support provided for formal-sector workers by the government.

“The problem is that many in authority don’t see sex work as work,” Ms Edwards said.

But some do. According to Rhonda Moore, Programme Manager at the National AIDS Programme, during COVID-19 the HIV Food Bank has expanded its reach to HIV-negative members of key populations. This includes female, male and transgender sex workers.

Ms Edwards points to the need for even more targeted social support, including for single mothers, migrants and those working in the interior.

The Guyana Sex Work Coalition’s strategy has been to pair the distribution of nutrition support and hygiene supplies with offers of HIV testing and safety reminders on COVID-19, HIV and sexually transmitted infections. According to Ms Edwards, this is a time of high stress and uncertainty and her clients are not necessarily able to absorb mass media messages. Text reminders and phone calls have been key approaches to ensuring that individual sex workers are informed and to address their unique challenges. Sometimes they need medication or money for transport. Many of the migrants need a safe space.

UNAIDS is embarking on a project with the Caribbean Sex Work Coalition to help national networks address sex workers’ knowledge, HIV prevention and social support needs during COVID-19. A major goal of the project is region-wide advocacy to encourage Caribbean governments to include sex workers in their planning and protection.

“Sex workers need to be included in national social protection schemes and many of them need emergency financial support,” said James Guwani, Director of the UNAIDS Caribbean Sub-Regional Office. “To win the battle against COVID-19 or HIV, we must give life to the principle of leaving no one behind.”

Feature Story

A safe space for key populations in Armenia

21 July 2020

21 July 2020 21 July 2020Arpi Hakobyan (not her real name), a former sex worker, lost her income after the COVID-19 pandemic hit Armenia. And then her parents threw her out of their home and took her passport. She had no place to go and no one to ask for help, until a friend advised her to contact the New Generation nongovernmental organization.

Opened by the New Generation in June 2020 in the centre of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, the Safe Space occupies a three-storey building that gives people living with HIV, members of key populations and women who have suffered from domestic violence a safe refuge.

“When the COVID-19 pandemic began, we started receiving calls from people who, because of their belonging to key populations or because they were HIV-positive, were discriminated against, found themselves without work, without support, sometimes without a home,” said Sergey Gabrielian, the head of the organization. “It is widely believed in our society that it is these groups that spread not only HIV but also COVID-19, which is why they are expelled from work or from society. These people have nowhere to get help from—they are not on any lists of recipients of government social assistance programmes.”

The Safe Space gave Ms Hakobyan a place in the shelter. The New Generation’s lawyer and psychologist reached out to her, helped to replace her documents and found her a job.

Referrals are made to the shelter by HIV service and human rights organizations across the country. Administrators, lawyers, psychologists and volunteers are on duty 24 hours a day. For the first three days, psychologists and lawyers work with the clients to find out their circumstances, help with documentation and understand how to proceed further. The average stay in the shelter is 15 days, with the maximum being a month.

“Of course, we are not a hotel, this small programme is not designed to support people for several months—there only 37 people who can be simultaneously in the shelter. And the demand for it is enormous,” said Mr Gabrielian.

A key feature of the shelter is a special HIV services room in which people can take an HIV test and get counselling and a referral to an HIV clinic. People who use drugs and need harm reduction services are referred to a nearby organization where such services can be obtained.

Mr Gabrielian said that when it became obvious that the fight against COVID-19 could hit the HIV epidemic hard, the New Generation’s employees decided to switch to a new way of providing HIV services—online consultations, the provision of tests and prevention materials by mail and the use of outreach workers.

“We insisted that programmes for key populations should not be stopped because of the coronavirus, otherwise, with the end of one pandemic, we will see an outbreak of the AIDS pandemic,” he said.

Today, the Safe Space project is supported by the Elton John Foundation, with support also from the Swedish Government. Negotiations are under way with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and UNAIDS on the future of the service.

“The coronavirus made us understand what new ideas could be included in the HIV service programme. It was these special circumstances that made us move on and look for new ways to support people in times of crisis,” said Mr Gabrielian.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Targeting sex workers is not the answer

08 June 2020

08 June 2020 08 June 2020When the Government of Cameroon ordered everyone to stay at home as part of the COVID-19 response, Marie-Jeanne Oumarou (not her real name) rushed to buy groceries and to gather her three children and move them the countryside.

With her children in safe hands, she hoped she could still work.

“I didn’t realize how hard it would be during confinement,” she said. “It doesn’t make sense for us sex workers.”

Ms Oumarou has learned the ins and outs of the couloirs—the avenues of small hotels where sex workers work—in Cameroon’s capital city, Yaoundé, over the past 10 years. Abandoned with her young children, she became a sex worker in 2010. She has grown to know the various older women, former sex workers themselves, who she pays to access safe places to work. COVID-19 changed her life overnight, though.

“Hotels closed, clients were rare, the police constantly around, I cannot survive,” she said.

Denise Ngatchou, Executive Director of Horizons Femmes, a nongovernmental organization that helps vulnerable women, said she was shocked to see how sex workers suddenly became a target.

“Police arrested and held women, disclosing zero information,” she said. “We felt powerless because the government had the upper hand with all the COVID-19 measures.”

Rosalie Pasma, a manager at one of the Horizons Femmes drop-in health centres, shrugged her shoulders in agreement during a Skype interview.

“Everything became much more complicated during COVID-19,” she said. “From women missing health check-ups because of transport issues to our legal expert not being able to access the police stations to defend arrested female sex workers, we felt the confinement in more ways than one.”

Ms Ngatchou piped in, saying that there was no reason to give up. Horizons Femmes vowed to stay open. A skeletal staff with condensed hours still provided HIV testing and other services by respecting preventive measures.

“People told us to stop all our on-the-ground awareness visits, but we held on as long as we could, giving coronavirus tips to women so they knew of the potential dangers,” she said.

They also kept handing out masks and started a crowdfunding project to purchase more protective gear. What really bothers Ms Ngatchou is how so many things happened before their eyes and they could do so little.

“Easing laws against sex work and ending arbitrary arrests of sex workers would really make an impact,” she said.

In the end, she believes that chastising sex workers only worsens the situation.

“Don’t you think that if sex workers hide they are more likely to work and infect themselves or become infected than if there was an infrastructure to help them?” she asked.

Reflecting on what she said, she added that this applies to COVID-19 as well as HIV.

In early April, UNAIDS and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects sounded the alarm on the particular hardships and concerns facing sex workers globally. They called for countries to ensure the respect, protection and fulfilment of sex workers’ human rights.

“Authorities have got to understand that we are not promoting sex work, we are promoting good health,” Ms Ngatchou said. “That’s the priority.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

Impact of the pause of US foreign assistance in Côte d'Ivoire

19 February 2025

Feature Story

Mobilizing COVID-19 relief for transgender sex workers in Guyana and Suriname

02 June 2020

02 June 2020 02 June 2020Twinkle Paule, a transgender activist, migrated from Guyana to the United States of America two years ago. As the COVID-19 crisis deepened, she thought of her “sisters” back home and in neighbouring Suriname. For many of them, sex work is the only option for survival. She knew that the curfew would starve them of an income. And she was worried that some might wind up in trouble with the law if they felt forced to work at night.

After making contact with people on the ground, her concerns were confirmed. She made a personal donation, but knew it was not nearly enough.

“Being somebody who came from those same streets, I knew we had to mobilize to take care of our community. I know about lying down at home and owing a landlord … about getting kicked out because you can’t afford to pay rent,” Ms Paule said.

She collaborated with New York activists Cora Colt and Ceyenne Doroshow, founder of Gays and Lesbians in a Transgender Society (GLITS Inc), to start a GoFundMe campaign. After launching on 12 May they’ve already raised enough money to cover rent subsidies for one month for six transgender sex workers. The money has been forwarded to Guyana Trans United (GTU), the organization for which she worked as a peer educator when in 2015 she left sex work behind.

That she can now use her position of influence to mobilize emergency relief is itself a stunning success. When she migrated, she’d felt herself tottering on the brink of suicide. The emotional weight of exclusion and injustice was bearing down.

One successful asylum claim later, she’s now a full-time communications student at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. She completed her high-school education last year—something she hadn’t been able to do in Guyana. While studying she worked as an outreach officer for GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis).

She seamlessly slipped into advocacy mode, addressing the city council last year about repealing New York State Penal Law § 240.37, a loitering law that is used to target transgender women. She immediately recognized that this was from the same tradition as the vagrancy laws she’d first been victimized by, and later fought against, in Guyana.

Ms Paule is acutely aware of how much her life prospects have changed due to migration.

“It just shows the difference it makes if somebody is given opportunities and the right tools to make other decisions in life. It showed me what I was lacking was adequate resources and the ability to go into an environment without having to worry about discrimination and violence. I am not saying everything is perfect here, but I don’t face the same level of injustice on a daily basis. I was able to access hormone therapy. And to me the most important thing,” she reflected, “is that I was able to go back to school.”

Her mother died when she was a child. Her father moved on with a new family. She was left in the care of his relatives. There wasn’t always enough money for her education. Some weekends she cleaned a church to earn some cash.

But poverty wasn’t the only challenge. Since she was very small she remembered feeling different. She did not have a label for what she felt, but instinctively knew it would not be accepted. At school she strained to stay under the radar. One day her heart skipped when a classmate said she sounded like an “antiman”—a Guyanese derogatory term for a gay person.

Over the years she repeatedly overheard adults in the household agreeing that she should be put out if she turned out to be gay. At 16 years old it happened. A relative spotted her “dancing like a girl” at a party. Now she was homeless.

Ms Paule sought refuge with other transgender women and, like them, used sex work to survive. The burgeoning regional movement to address the needs of vulnerable and marginalized communities had an impact on her life. From the newly formed Guyana Sex Work Coalition she learned about safer sex and accessed safer sex commodities. When some of her peers started going to conferences they found out for the first time that there was a word for their experience. They weren’t “antimen”. They were transgender.

But life on the street was brutal. If someone was robbed or raped they could not report the crime.

“The police tell you plain, “Why are you coming here when you know prostitution and buggery are against the law?”,” she remembered.

She said sometimes rogue police officers threatened to charge them and extort money from them.

Once the police locked up her and other transgender women together with men at the police station and threw condoms into the cell—a green light to the other detainees. She was a teenager at the time.

She accompanied a friend to the police station to make a domestic violence report one day. Instead a policeman told her, “You are involved in buggery. I am locking you up.”

In 2014, a group of them were arrested for sex work in Suriname. Among other indignities, a prison guard forced them to disrobe and squat outside their cell, in the presence of other detainees.

Seven years ago, one of her friends was killed, her body was thrown behind a church. There was no investigation.

Trauma after trauma. It takes its toll.

Even when nothing happens, there is lingering fear. Will I be put out the taxi? Will people insult me on the street? Will I be mistreated because of what I’m wearing?

“The girls take it like it’s their fault,” Ms Paule reflected. “Even in my personal experience I felt people had a right to do me things because I was not behaving in accordance with societal norms.”

Even as she stepped into advocacy, she didn’t feel whole. She attempted suicide once and began having a drink or smoke before turning up to work. Two years ago she was unravelling. Now she’s rallying forces in the service of her community.

Ms Paule credits the work of organizations like the Society against Sexual Orientation Discrimination and GTU for advancing the dialogue around inclusion in Guyana.

“What is still missing is safety and equity for the community,” she insisted. “We need a state response to say, “These people should be taken care of”. The trans community has no jobs, we are bullied out of school, we suffer police brutality. These things are wrong. We need more robust action from our elected officials.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“We cannot provide only HIV services while sex workers are hungry”: Thai community organization steps in

01 June 2020

01 June 2020 01 June 2020When the Thai government ordered the closure of entertainment venues in the country in March, it didn’t just signal an end to pulsating music and rounds of drinks shared with friends. It also signalled the start of difficult times for an estimated 145 000 sex workers living in Thailand.

Initially, Service Workers in Groups (SWING), a Thai national organization providing HIV services and advocating for sex workers’ rights, received requests from sex workers for the most basic of needs—food. As requests began flooding in, it became clear that without a source of income many sex workers were unable to cover the cost of daily expenses, housing and medicine.

“When the COVID-19 outbreak began, nobody was talking about sex workers, and no measures were in place to help them,” said Surang Janyam, Director of SWING.

Spurred by growing concerns about how the outbreak has impacted the lives of sex workers, SWING, in collaboration with Planned Parenthood Association Thailand and Dannok Health and Development Community Volunteers, with support from UNAIDS, launched a community-led rapid assessment of 255 sex workers from Bangkok, Pattaya and Dannok and community-based organizations throughout the country.

The outbreak has had a severe socioeconomic impact on the lives of sex workers, further exacerbated by the lack of social protection measures. According to the findings from the rapid assessment, 91% of respondents became unemployed or lost their source of income following the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. Three quarters of the respondents could not make enough money to cover daily expenses and 66% could no longer cover the cost of housing.

Ms Janyam spoke about the difficulties faced by sex workers and how the priorities for SWING’s work have shifted. “As a sex worker-led organization, we cannot provide only HIV services while sex workers are hungry and lack the basic needs to survive,” she said. She explained that many of the sex workers expressed that they were not eligible for the government assistance of 5000 baht. Answering the call for help, SWING staff have taken to the streets to raise donations and deliver food to sex workers in their network.

Widespread coverage in the media and on personal blogs has catalysed a public conversation about the lack of social protections for sex workers. Ms Janyam also points to donations from local businesses and visits from younger people wanting to help as promising signs of how wider audiences are becoming more engaged on the topic of supporting sex workers in their communities.

The COVID-19 outbreak has also contributed to new challenges for HIV prevention. Fears of COVID-19 have deterred people from visiting clinics to be tested for HIV. Additionally, the rapid assessment findings revealed that almost half of the sex workers surveyed had difficulty accessing sexually transmitted infection screenings. In response to those observations, SWING partnered with a hospital capable of conducting COVID-19 testing, thereby drawing in sex workers interested in being tested for COVID-19 and creating an opportunity to counsel them about HIV tests. These changes in practice show possible synergies in prevention measures for both COVID-19 and HIV prevention and treatment.

“The results from the rapid assessment have proven to be a strong tool for advocacy and decision-making. Stakeholders of the AIDS response have collectively identified and started to implement priority actions as an immediate response to the needs of sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Patchara Benjarattanaporn, UNAIDS Country Director for Thailand.

Ms Janyam reflects on what this will mean for SWING’s work and recalls the ways in which sex workers were not afforded the same social safeguards as others—they were forgotten. “We must transform ourselves. Community-led organizations must apply a holistic and comprehensive approach, providing immediate basic needs, integrating a package of prevention for both COVID-19 and HIV health services, as well as mental health support for sex workers,” she said.

She affirms that SWING and other charitable groups will continue to seek donations and provide basic provisions for sex workers, recognizing that the need for assistance will remain long after the situation eases, long after the bars and restaurants have reopened.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Kenyan sex workers abandoned and vulnerable during COVID-19

20 May 2020

20 May 2020 20 May 2020During the more than a decade that Carolyne Njoroge worked as a sex worker, she never saw such violence against her peers. Now working full time for the Kenya Sex Workers Alliance (KESWA), she said that the COVID-19 lockdown threw everyone into disarray.

“At the outbreak, no one was prepared for the coronavirus,” she said. “It’s not like the rains that we know and can prepare for.”

The government’s lockdown measures to limit the spread of the virus—a dusk-to-dawn curfew and shutting of bars and nightclubs—have left sex workers in Kenya to either work during the day and be very visible or to break the curfew at night.

So far, KESWA has reported that more than 50 sex workers have been forcefully quarantined during the early days of the pandemic, and women have been arrested for not adhering to the social distancing rules and obligatory mask-wearing.

“How do you expect women to adhere to these measures when they cannot feed themselves and their families and many of them don’t even have homes?” Ms Njoroge asked.

Kenya does not criminalize sex work. However, the law forbids “living on the earnings of sex work” and “soliciting or importuning for immoral purposes,” which Ms Njoroge said means that the women work in a grey area. “It’s a very hostile work environment and sex workers are the first to be violated because they say our work is not work,” she said.

Phelister Abdalla, a sex worker living with HIV and KESWA’s National Coordinator, said, “Sex workers need to be protected, but if we are told to stay at home we need to be given food.”

The government has not released funds or directed aid to sex workers, so KESWA started a fundraiser to dispatch hygiene packs, which include hand sanitizer, masks and menstrual pads, as well as food baskets.

Ms Njoroje said that 100 sex workers from the informal settlements had benefitted. “Our challenge is keeping up with demand, so we are reaching out to others for help,” she said.

Ms Abdalla said that fighting the pandemic together is key. “If we want to end COVID-19, we should not be judged by the type of job we do,” she said. “We are first and foremost Kenyans, so treat all of us equally.”

Fifty-seven Kenyan civil society and nongovernmental organizations, including KESWA, drafted an advisory note to the Kenyan Government to urge it to put in place safety nets to cushion the communities and people who cannot afford to not work. They also urged them to stop security forces from enforcing measures around social distancing and curfews. The note adds, “We cannot use a “one size fits all” approach for COVID-19” and calls upon the United Nations leadership to help safeguard the progress.

The Kenyan Government, through the National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP), in partnership with county governments, implementing partners and donors continues to work to ensure the continuity of KP service delivery during the confinement measures. NASCOP issued technical guidance to all services including information, education and communication materials e.g. posters, setting up virtual coordination platforms, capacity building of service providers on HIV in the context of COVID-19 and they have instituted advocacy efforts to raise resources to ensure that service providers, including outreach teams, and Key Population led groups have personal protective equipment (PPE) and sanitizers. Mobile dispensing services for people who use drugs and tailored outreaches have been established to enhance service delivery along with the formation of virtual psychosocial support groups distribution of food baskets to the very vulnerable and help/hotlines for violence response have been sustained.

UNAIDS collaborates with governments to ensure that international human rights law are respected, protected and fulfilled, without discrimination, in line with state obligations, including in times of emergency.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

24 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

20 February 2025