Asia Pacific

Feature Story

Compassionate care for people who use drugs in Thailand

26 June 2023

26 June 2023 26 June 2023At the Ozone Foundation clients talk about their drug use with as much openness as they discuss their jobs or families. In the yard of their Bangkok drop-in centre we sit under the cannon ball tree. Prapat Sukkeang shares his story first.

He is the Chair of the Thai Network of People who use Drugs (ThaiNPUD). He’s used substances of some kind for more than three decades. He says he started because of “small problems”. Once his family found out, he was immediately alienated: “the community and society around me became distant,” he remembers. Mr Prapat still uses. He might have yaba—a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine—once a month.

“Ozone is the place I get knowledge about my health and about drug use. They give you information for your safety. I think without Ozone I might have overdosed,” he says plainly. “I feel very good to come here with service providers who see us as friends and provide healthcare services according to our needs. I feel respected. When we go to other places we always feel like criminals. If we go to a hospital they serve us last or reject us to get treatment. The service that we get is not equal to others.”

Jamon Aupama, a motorcycle taxi driver, lives with his wife in Bangkok. He goes to a state-run methadone clinic to avoid heroin withdrawal. He wishes he could take the methadone home and didn’t have to go there every day.

The experience at Ozone is different. Here the service delivery more closely matches his needs. He relies on Ozone for tests, clean equipment and “to hang out with friends”. He also goes for information.

“They give me detailed advice on how to protect myself from illness,” he says. “Some Ozone staff know personally about drug use, some do not. The trust comes from knowing them and the way they are trained,” Mr Jamon says.

From the ‘war on drugs’ to a more humane drug law

This people-centred service—and even these honestly told stories—were unimaginable just two decades ago. During the first three months of Thailand’s 2003 “war on drugs”, police killed almost three thousand people. Human rights groups reported widespread arbitrary arrests, beatings, forced confessions and compulsory detentions for “rehabilitation”. Use of HIV services by people who use drugs declined sharply. Terrified, people shrank into the shadows.

This chaotic context was the spark for Ozone’s formation. Back then they set up their first drop-in centres as safe spaces where clients could take a shower, have a meal and share their experiences.

Today the political and social climate is far different. A new Narcotics Law introduced in December 2021 provides for differentiated sentencing on drug crimes and alternatives to imprisonment for some offences. For the first time, the health and wellbeing of people who use drugs are being considered. There are provisions for harm reduction although it isn’t precisely defined. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) notes the continued existence in Thailand of compulsory treatment centres, deemed by the United Nations to be ineffective and a violation of human rights. Still, this more humane drug law is a first in Southeast Asia.

“Community-based treatment should be the way to provide care. Through community literacy we can understand the patient and the situation they face to get them to have a good outcome,” says Dr Phattarapol Jungsomjatepaisal, Director of the Department of Health Service Support at the Public Health Ministry.

Ozone’s holistic service package

Ozone Foundation’s Director, Verapun “Noy” Ngammee, explains that the organisation’s raison d'être is to respond to clients’ unique situations.

“They have bad experiences with stigma and discrimination,” he starts. “It’s difficult to trust people. Many of them have been suffering for a long time. We need to have peer organisations that are community-led and driven or you would not get clients coming to services. We respect the human dignity of all people. And we believe that safety is available to people before, during or after drug-use.”

Their model identifies each person’s specific risks and needs. They’ve found that much of the harm clients experience is not directly due to drug use, but rather to the environment—anything from the inability to access healthcare to harassment by police. Ozone employs a holistic approach that puts the client at the centre. One person might only require harm reduction counselling and tools while another is ready for support to quit.

The organisation collaborated with C-FREE, a laboratory service, for screening and monitoring of Hepatitis B and C, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They also offer the Hepatitis B vaccine. Research nurse Kewalin Kulprayong says her team has a welcoming approach.

“Clients know it is not a hospital,” she says. “It is safe. They can speak about everything here, drugs also.”

A doctor is available once a week. Some conditions can be treated at Ozone. In other cases, clients are referred to government facilities but with the benefit of peer support. These services are critical. An estimated eight per cent of people who inject drugs in Thailand are living with HIV while Hepatitis C prevalence is 42%.

"Universal Health Coverage in Thailand paves the way for comprehensive care, including essential services like HIV testing, pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP, treatment referrals, and screening and treatment for STIs and Hepatitis C. However, despite their inclusion in benefit packages, individuals who inject drugs face significant barriers due to pervasive stigma and discrimination, including self-stigma," says Patchara Benjarattanaporn, UNAIDS Country Director. “In this landscape, key population-led health services like Ozone’s emerge as invaluable one-stop shops, providing stigma-free care and ensuring that no one is left behind, especially those who use and inject drugs.”

Looking toward the future

Each Ozone client has their own dreams. One wants to run for political office. Another hopes to get his gender affirming surgery soon. A third imagines a life in the countryside with a small farm: “Not too many people,” he says with a chuckle. “Then I get in more trouble”.

He came to Ozone because he was depressed, anxious and dealing with a sexually transmitted infection.

“I did not have the confidence to go to a hospital and say, ‘I want treatment’. But I knew if I did nothing it would get worse. At Ozone they understand. They give me guidance. They’ve advised me to use social security to get mental healthcare. They tell me ‘people make mistakes sometimes’. I am one of those guys who makes many mistakes,” he confesses with another uneasy laugh. “But now the mistakes are getting less.”

A group of journalists visited the Ozone Foundation as part of the UNAIDS, UNDP, APN Plus and USAID/PEPFAR Southeast Asia Regional Workshop on HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination in Bangkok, Thailand on June 8, 2023. Learn more about this novel training.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

A rainbow of hope for LGBTQI+ people in rural Japan

17 May 2023

17 May 2023 17 May 2023For many years Mami taught at a state school in Kanazawa, Japan. When she started transitioning and dressing in a less masculine way, her colleagues and supervisors frowned upon it. Finally, she was fired.

As a transgender woman in a small, conservative city, Mami struggled to find another job and felt very isolated. “When a friend invited me to work at the Kanazawa Rainbow Pride community centre, I was happy to have a place where I was accepted,” she said.

Founded in 2022, the Kanazawa LGBTQI+ centre is in a 150-year-old tea house in what was the city’s former Samurai marketplace. The sliding panels allow for a variety of configurations depending on gatherings. Mami and her friend, Kennosuke Okumara, Head of the Kanazawa centre’s secretariat, were serving tea and coffee in the open bar kitchen to visitors.

“Before I worked in Tokyo but I returned to my native city,” Mr Okumara explained. “The problem was that there were and are no options for gay people here,” he said. Mr Okumara lives with HIV and laments the fact that HIV and LGBTQI+ issues are still taboo. “There is so little information, it is a shame and I am here to share my experience and share more awareness,” he said.

Mixing a green tea in a small cup with a bamboo whisk, Mr Okumara in his apron paused and looked at Mami. “This is a safe space for all here,” he said.

Diana Hoon, the centre’s co-President called the centre a beacon of hope. “We are like a lighthouse in a very conservative, patriarchal society,” she said. Showing off the many pamphlets and flyers varying from knowing one’s HIV status to the Pride parade in the city to books about coming out in the makeshift library, Ms Hoon said that the centre not only was attracting more people, they also had 10 volunteers helping out... many of whom are mothers.

"Our parent seminars about LGBTQI+ have had a lot of impact,” she said. “People share stories about their children and a connection is made.”

As a Singaporean living with another woman who is originally from Kanazawa, Ms Hoon feels like she is doing her part to provide a lifeline for people and push for more acceptance.

“Among our many priorities we do HIV awareness as well as advocate for gender neutral toilets, gender neutral school uniforms and most importantly marriage for all, which does not yet exist in Japan,” she said. She also hopes that within five years they can add a shelter to house LGBTQI+ people.

In her mind there have been incremental steps. “Transgender people have been more outspoken of late and we have LGBTQI+ champions among the community,” she said.

Such a role model is Gon Matsunaka, Founder and former President of the Pride House Tokyo consortium and the Director of the Marriage for All movement in Japan. A former advertising executive for one of Japan’s top firms, Dentsu, Mr Matsunaka hid his sexuality for decades. “For me there was no future in my rural hometown, so I left for Tokyo,” he said. He then studied in Australia, worked in Tokyo as well as New York City and ultimately left his firm.

He came out as gay in 2010 and fixated on providing a community centre in Tokyo. The Olympic Games seemed like a golden opportunity.

The COVID pandemic struck, putting a lot of projects on hold but Mr Matsunaka and his team did not give up.

“In May 2020, survey after survey revealed that LGBTQI+ youth felt unsafe at home or they had lost touch with people, this really motivated me,” he said. He had secured 15 sponsors for a temporary LGBTQI+ safe space during the Olympic and Paralympic Games, called Tokyo Pride House. With the postponing of the Games however, the centre was cancelled.

The team persuaded the sponsors to shift their funding and create a permanent space. Years after the Olympics, Tokyo Pride House still stands proud within walking distance of the popular queer-friendly Shinjuku area in Tokyo.

In Kanazawa, Mr Matsunaka had linked up with Ms Hoon to start a Pride parade in 2021. Out of that success came the idea of a community centre.

Mr Matsunaka is particularly proud that the prefecture (city district) contributed half the funds to the Kanazawa Nijinoma centre. The rest was a result of crowdfunding.

Beaming in the Tokyo Pride House surrounded by rainbow flags, he said, “I never dreamed of this and never imagined it could be possible especially in a small city like Kanazawa.”

In his mind, women have been key. “Women have 2nd rank to men especially in rural areas like Kanazawa, so they have been our greatest allies to change the patriarchal mentalities,” he said. “Mind you we have a lot more work ahead, but I only want to go forward not backwards."

On International Day Against Homophobia, Biphopia and Transphobia (IDAHOT), UNAIDS stands in solidarity with the LGBTQI+ community. We must unite and celebrate diversity; a society where everyone, no matter where they live or whom they love, is able to live in peace and security; a society where everyone can contribute to the health and well-being of their community.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Cook Islands’ original path toward equality

27 April 2023

27 April 2023 27 April 2023On April 14th members of the Cook Islands rainbow community assembled at parliament with colourful flags and cautious optimism. It turned out to be the day they’d been working toward for the last twelve years. Parliament removed laws prohibiting consensual sex between men, striking out sections of the Crimes Act that had been on the books since the turn of the 20th century.

“This decision by Cook Islands is part of a wave of global progress around abolishing harmful laws,” noted UNAIDS Asia Pacific Regional Director, Eamonn Murphy.

“This was a huge historical moment,” said Valery Wichman, President of the Te Tiare Association, the nation’s oldest lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) organisation. “It’s not just a win for the community, but also a shift in terms of our nation maturing and upholding the constitutional rights of all people.”

Ms Wichman, an attorney and public servant, is also an akava'ine—a Māori word meaning transgender woman. She attests that the anti-LGBT laws which made so-called “sodomy” and “indecent acts” punishable by imprisonment reinforced prejudices. This contributed to the LGBT community’s exclusion, harassment and bullying. She has herself experienced being mocked and assaulted.

“A lot of people chose not to live here. It was too hard for them to endure their family’s and society’s judgment. The idea that you are not worthy has carried down from parents to children and has affected how we have been treated by our peers. A lot of trans women have not gone to the doctor because they have been misgendered and have felt disrespected. There have been cases where they ended up dying,” she said.

The journey toward law reform started in 2011. The spark was the discriminatory response to the nation’s first HIV diagnosis. Te Tiare led the advocacy charge with support from organisations including the Cook Islands Family Welfare Association.

A Crimes Bill drafted around 2013 removed the discriminatory clauses. In 2017 parliament set up a Standing Committee to review its raft of proposed revisions. Support for civil society to prepare submissions outlining public health grounds for reforms was provided by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the lead agency amongst the United Nations Joint Programme on HIV and AIDS working on effective democratic governance and issues affecting sexual and gender minorities.

But following a political change the next year, the committee’s Chair recommended retaining the ban on gay sex. What’s more, he proposed a new section criminalising sex between women. The bill remained in limbo for years. Reform efforts seemed to hit a wall.

A strategy of public dialogue and political engagement rooted in Cook Islands culture enabled a breakthrough. Pride Cook Islands (PCI) was formed as a sister organisation to Te Tiare, focusing on this public advocacy branch of work.

“Obviously we are in a unique situation as a small, conservative, religious population,” PCI President, Karla Eggelton began. “The work of advocacy becomes more delicate when you are living beside people making these decisions for you. We welcomed support from international allies, but we knew we had to do this our own way and have our own approach that is mindful of the situation and culture we live in.”

First TCI tackled messaging. There were deep deliberations around word choice. The mandate was to keep the conversation simple. Ultimately the cause was framed as an equality issue. The rallying cry became, ‘don’t make us criminals in our own country’.

The organisation stayed in communication with policymakers on both sides of aisle. They not only explained their position, but sought to understand politicians’ concerns.

The group met with traditional leaders who are grassroots decision-makers. Village communities were invited to have conversations during public meetings.

“It offered an opportunity for us to understand the misperceptions. We were able to explain that all we are asking for is to not be made criminals. People said, ‘we don’t want to send you to jail, we love our neighbours and our family’,” Ms Eggelton remembered.

The organisation’s patron is Lady Tuaine Marsters whose husband, Sir Tom Marsters, is the British King’s Representative. Lady Marsters frequently attended consultations. Other spokespersons included parents and people with standing in the church. At times supporters were invited to simply stand in solidarity. But anyone who would speak was carefully prepared.

“We spent hours articulating what we would say. We reaffirmed our pledge to not become emotional. We had to keep each other in check to make sure we did not say anything we could regret,” Ms Eggelton outlined.

Then came an effort to increase visibility. The call for equality was largely coming from the LGBT community. They needed other people to demand the same. So PCI embarked on a campaign for people to show their support either by lending their voice to the public dialogue or flying the rainbow flag. The group distributed free flags, urging people to fly one for their daughter, son or grandchild. From restaurants to bars, t-shirts to earrings, the display of support resonated.

A first-of-its-kind pride ad on TV, newspapers and radio challenged Cook Islanders: “We are good enough to be your teachers, nurses, choreographers, dressmakers and orators… but not good enough in the eyes of the law. We are already part of your community, we are just asking you to recognise us as equals.”

This visibility and advocacy work was supported by UNDP through the Being LGBTI in Asia and the Pacific program. PCI developed a project to strengthen the digital capacities of community organisations. A critical outcome was the Pride Pledge Cook Islands initiative with the business community which provides visible safe spaces for LGBT people.

“The UNDP support was instrumental in promoting acceptance and awareness and utilising digital tools to share our message,” Ms Eggelton said.

TCI conducted frequent polls to gauge public sentiment. At the start of the process they lagged behind reform opponents. But by the time would-be Prime Minister, Mark Brown, made an election promise to change the law last year, public sentiment had tilted.

“Once we were able to establish that it was really about equality, then we saw a changing of the tide,” Ms Eggelton reflected.

Ultimately the entire government bench voted in favour of an Amendment Bill while opposition leader, Tina Brown, and two of her Members of Parliament also supported.

Renata Ram, UNAIDS Country Director for Fiji and the Pacific, noted that seven other countries in the Pacific region retain laws criminalising same-sex relations.

“The Cook Islands example proves that along with law reform we can have national dialogues about inclusion, justice and equity,” Ms Ram said.

At a national ceremony marking the end of the South Pacific cyclone season the rainbow community gathered once more, this time to give thanks.

“We want to make sure people understand our gratitude for everything that has transpired and for everyone who worked hard to achieve this,” Ms. Eggelton said. “Our community is now recognised through the eyes of the law as being equal. Now people can feel safe, not like second class citizens.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Press Release

UNAIDS welcomes the decriminalisation of same-sex relations by the Cook Islands parliament

15 April 2023 15 April 2023BANGKOK, 15 April 2023—UNAIDS applauds today’s decision by Cook Islands lawmakers to remove laws prohibiting consensual sexual acts between men from the Crimes Act. By decriminalising sex between same-sex partners, the Pacific nation joins a global movement toward affirming the human rights to non-discrimination and privacy.

“Cook Islands’ latest move is part of a wave of global progress around removing laws that harm. It will inspire countries across the Pacific, Asia and the world to follow suit. Decriminalise, save lives," said UNAIDS Asia Pacific Regional Director, Eamonn Murphy.

Criminalisation of same-sex relations undermines the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. Punitive laws reinforce stigma and discrimination against LGBT people, undermining their access to the rights, remedies and opportunities available to other people. Such laws also obstruct access to vital services, including sexual and reproductive healthcare.

"This decision by Cook Islands will save lives,” said Mr Murphy. “The abolition of punitive and discriminatory colonial laws across the world is essential for public health, including for ensuring the end of AIDS.”

Bi-partisan support for the Crimes (Sexual Offences) Amendment Bill demonstrates that policy-makers, civil society and communities can dialogue to develop laws that create more just and equitable societies.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

The power of visibility — My story as the first person who came out as a person living with HIV in Fiji

18 April 2023

18 April 2023 18 April 2023Jokapeci Cati is the Program Manager and founder of the Fiji Network for Positive People (FNP+). This is her self-told story of how she became the first person living openly with HIV in Fiji.

I grew up in the harbour town of Suva. I was brought up in the Seventh Day Adventist Church. During youth camps we had two sessions on HIV. To me it was just a session. I had this perception that I am not promiscuous so I can’t become HIV positive.

I got married at 21 and got infected in my marriage. I was diagnosed in 2000 but I suspect I was living with HIV since 1999. My husband was sickly and became bed ridden. I did not blame him. I felt like he got infected before we were married and did not know he was living with HIV. In 2003 he died due to AIDS-related causes. He was 31.

We did not have treatment in Fiji at that time. People living with HIV were just monitored. When I was diagnosed they told me “you have to look after yourself because you can die”. In the initial stages there was depression, denial and stress. But as soon as I got diagnosed one of my dreams was to meet another person living with HIV.

With my family there was no change in the way they treated me. It was support from the word go. I did not see any element of discrimination from my parents and siblings.

Going public

Coming out was not an overnight decision for me. It took me six months to juggle the pros and cons. Somehow my mind was not dwelling on the negative. Because there was no support system in place at the time, I felt the need to speak out.

So I started with the church. I went to the pastor and told him of my diagnosis. Then I had to disclose to my church community. The hardest bit was opening up to your very own people. Once I gained the support of the church I spoke to the Council of Chiefs, Fiji’s traditional leaders forum. Because those platforms gave me a positive reception I then went to the media because I felt I was ready to speak to the nation.

Organising and advocating

In 2003 I was privileged to meet the right people at the Ministry of Health and we coordinated the first meeting of FNP+. By 2004 I got the organisation registered, up and running.

From the start I was advocating for treatment because I could see my first husband dying. The Ministry of Health’s HIV coordinator at the time, Maire Bopp Dupont, connected us to the Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV. That is how I got to know that other countries in the region were offering treatment. We went to the Council of Chiefs and Parliamentarians to advocate. The Health Ministry at the time was saying “we are not ready… we need to put the systems and structures in place”. I think because we came out publicly it put some pressure on them. The very next year, in June, treatment was available.

It was exciting. For the first time we felt the advocacy was worth the sacrifice. Our work involved talking to nurses, doctors and civil society organisations that were part of the care team. I started antiretroviral therapy five years ago when we adopted the “treat all” policy. It is so exciting that we are able to take treatment with the assurance that we would live! And it is for free!

Living life fully

I did not let HIV decide my future. Because of being part of the FNP+ management team I found the need to venture into education. I got a degree in psychology and social work from the University of South Pacific.

When I lost my first husband I was in this dilemma about whether to have children. I met my current husband in the HIV organisation. When we decided to have children, it was a public affair in Fiji. I was an HIV positive, pregnant woman. It was a learning curve for me and the entire nation.

The UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for the Pacific, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, was Fiji’s President at the time. He made it his business to come to the hospital during my delivery and my first son’s HIV test. He wanted a copy of my son’s HIV negative test result. This became his advocacy document. He has been spreading the message since then that there is no need to discriminate against women living with HIV who want to have children. It’s time we support them through prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) treatment. I am now the mother of three HIV negative children.

The way forward

We are working to get FNP+ funding from the Global Fund to continue our national activities and regional support. I’m glad the focus is now on community-led monitoring and services and that it’s coming from the donor’s mouth.

Other Pacific countries don’t have networks of people living with HIV. Fiji is the only one. People throughout the region are living in isolation. Our second piriority is to organise at the regional level.

Our third challenge is that although everyone who is living with HIV is encouraged to take treatment, we have stockouts. At one point we weren’t getting Dolutegravir so people had to change to a combination of drugs until it became available. Labs are also a challenge, especially the turnaround time for viral load tests. If FNP+ does not continue to apply pressure to address these issues people would suffer silently.

HIV in a small island developing state

For sure people living with HIV from key population communities have had a more difficult time. They were ostracised, they were discriminated against. I did not face that. There was a time, around 2004 and 2005, when people who died due to AIDS had to be burned at night before the sun rose! The stigma and discrimination are not as bad as that now, but they still exist.

I think in the Pacific it is really hard to come out with your HIV status because of our small size. We have these connected communities and if someone comes out it is easy to trace who else could be HIV positive. We have this communal upbringing so people don’t want any negative repercussions for their families.

When other people living with HIV meet me, they are happy. They want to come out and speak, but they don’t know how. Now there is funding for this community engagement in more Pacific countries. We just need to give them support and a bit of time.

Fiji recently received technical support for the seventh cycle of Global Fund applications and the Indo Pacific HIV Prevention Program supported by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). UNAIDS Pacific supports peer network meetings to encourage sharing among PLHIV. UNAIDS also recently collaborated with Rainbow Pride Fiji Foundation, the Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM) and the National Association of People with HIV Australia (NAPWHA) to develop a PLHIV booklet in the local languages. This booklet provides information on living with HIV and helps empower PLHIV to take control of their health and wellbeing. This project is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and DFAT.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Beyond transgender visibility: India works toward employment equity

31 March 2023

31 March 2023 31 March 2023Ratrish Saha is a transgender woman from Kolkata, India. Even with seven years’ work experience, she was anxious about applying for a new job last year.

“Finding a job is never easy being a transgender woman. I would get rejected with statements like ‘currently no LGBT hiring is going on’ or ‘we do not have facilities to accommodate a trans individual in our office’,” she recalled. But through the Transgender Welfare Equity and Empowerment Trust or TWEET Foundation, she was paired with suitable opportunities in corporations that have received sensitivity training. She soon landed the position of associate consultant for Siemens Technology in Bangalore.

She said of the interview process: “I only talked about my skills and no gender explanations were included in those conversations.” An ecstatic Ms. Saha says she is “grabbing the opportunity… putting my all into it”.

Transgender people in India now have a new pathway toward dignified work thanks to a collaborative effort between communities, government and development partners.

Ahead of the International Day of Transgender Visibility, the UNAIDS Country Office for India and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) supported the Trans Employment Mela (Job Fair) in New Delhi. The initiative was jointly hosted by the National Institute of Social Defence, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, TWEET Foundation and In Harmony, a diversity consulting firm.

The programme aims to accelerate the socio-economic inclusion of the trans community by bringing awareness about their issues to mainstream corporations and providing a platform to connect them with job roles in inclusive organisations.

“Not only does this approach provide an opportunity for dialogue between government representatives, civil society organisations, and businesses, but it facilitates access to skills training, career counselling, entrepreneurship support and mentorship support,” Maya Awasthi, Co-Chair and Co-founder of TWEET Foundation explained.

India’s 2019 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act prohibits employment discrimination against trans people in either the public or private sectors. While stakeholders point to aspects of the law that could be strengthened, they acknowledge that the wide-ranging anti-discrimination provision creates a pathway toward building a more inclusive culture and pursuing redress when rights are violated.

Addressing employment access inequality is relevant to the HIV response. In 2021 HIV prevalence among transgender people in India was 3.8%, almost 20 times the national average. A study commissioned by India’s National Human Rights Commission found that in 2017 just six percent of transgender people were formally employed in either the private or non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector. About 5% engaged in sex work and domestic labour respectively. Thirteen percent sold food and other items while 11% reported begging.

“There are many ways in which higher paying and consistent work can reduce HIV vulnerability,” explained UNAIDS Country Director for India, David Bridger. “By addressing the inequalities that have unfairly pushed trans people away from opportunities, we can help build a more empowered community in which people fulfil their potential, enjoying better health and wellbeing in the process.”

The 2017 Human Rights Commission study found that around half the transgender population never attended school. Several development partners are supporting initiatives to provide the community with education opportunities in a stigma-free environment as well as skills training to promote self-reliance.

Aarav Singh is a transman who had been out of work for six months. He was able to score a human resource internship at Roop Automotives through the Trans Employment Mela.

“This is a sensitised, trans inclusive organisation where I've faced zero issues with documentation. Not only me but my friends have scored great opportunities with some of the leading trans inclusive companies,” he said. “I hope this continues.”

But while the Trans Employment Mela beneficiaries acknowledge the community dimension of their challenge, in other respects they feel like any other hopeful young professional or recent graduate.

Yumnam Thawalngamba Meetei completed an MBA in 2022 but found it difficult to get a management position “or even a small job”.

“With the help of TWEET Foundation I got into Mahindra Logistics Limited as an Executive for Talent Management and Organisational Development in Mumbai. I am thankful for this job to pave a path for my success,” he said.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Healthcare access is fraught for trans people in Asia and the Pacific. Communities are working to change this.

31 March 2023

31 March 2023 31 March 2023Zara Fauziah is a transgender woman from Indonesia. She learned she was living with HIV in 2017, but for four years coped with her diagnosis alone. The hospital where she could receive treatment wasn’t welcoming.

Rere Agistya, another Indonesian transwoman, explains why: “If we come to get services or to get checked for HIV, we often get lectures with the purpose to ‘cure’ us. Most of the time they blame our activities: ‘Well you know you are a man. Why do you want to be a woman?’”

Many countries in the Asia Pacific region lack national guidelines on transgender care. As a result, healthcare workers often miss the mark on delivering non-discriminatory and medically appropriate services.

This is a critical gap for the AIDS response given the disproportionately high HIV rates among transgender people. HIV prevalence for the community is around four percent in India and the Philippines. In Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, roughly one in ten transgender women lives with HIV.

Samira Das lives in Chingrihata, India. She is a Hijra (Hijras include transgender and intersex people).

“When my family members came to know I am HIV positive they separated my utensils and other things. They got me treated but they kept me in isolation. I stayed there, bearing everything,” she said.

“People nowadays don’t die from HIV. They die from stigma and discrimination surrounding their physical and mental health and sometimes surrounding their sexuality as well as other sociodemographic factors,” Indonesian transgender physician and researcher, Dr. Alegra Wolter explained. “I’ve seen trans people who stop HIV medications because they don’t get the proper mental health services.”

But Dr. Alegra emphasises that the issue goes beyond HIV. Transgender people have inadequate access to everything from primary healthcare to hormonal therapy. With support from the Robert Carr Fund, Youth LEAD partnered with the Asia Pacific Transgender Network (APTN) to conduct a situation analysis on trans youths’ access to healthcare in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.

“We conducted the study to raise the visibility of young trans people in the conversation around trans rights and healthcare, especially since they experience stigma and discrimination both as young people and as trans people,” explained Leo Villar, Youth LEAD’s Communications and Project Officer. “The study showed that young people seek knowledge from peers and undergo do-it-yourself treatments. This could lead to incorrect healthcare information and the misuse of hormones or HIV drugs.”

Preliminary findings from the online study commissioned in December 2022 found that many transgender people between ages 18 and 30 endure systemic discrimination and abuse when accessing healthcare.

“I experienced an incident where an officer asked for my identification and made fun of me. This made me feel uneasy as it occurred twice. As a result, I have been avoiding healthcare services,” one survey respondent said.

Researcher, Dr. Benjamin Hegarty, noted that more than half (52%) the study participants strongly agreed that they worried about being negatively judged because of their gender identity or sexuality when accessing care. Around one-third thought this could negatively impact their evaluations and diagnoses. Asked about their top priorities for healthcare and funding, the majority of respondents pointed to the need for gender clinics, access to universal health coverage as well as counseling and mental health services. Also high on the list were trans-related health research and education about gender diversity.

APTN has just launched the Towards Transformative Healthcare Module. This is a self-paced, interactive online training which is designed as an introductory resource on trans competent and gender-affirming healthcare for medical professionals and other healthcare workers in Asia and the Pacific. This includes those working in primary care and community-based health services.

The module uses a rights-based approach that departs from “pathologising models” that treat transgender people as abnormal. Instead, it promotes transformative and culturally sensitive care. Twelve topics are covered including gender diversity, mental health, sexual and reproductive health and gender-affirming care.

“Through this module, healthcare providers and trans clients can learn how to work together to create positive change and achieve HIV epidemic control,” said APTN Executive Director, Joe Wong. “We are emphasising core principles which can be applied by healthcare professionals even in areas with limited resources and training opportunities.”

The Southeast Asia Stigma Reduction Quality Improvement (QIS+D) Network and Community of Practice are co-convened by the University of California, San Francisco, the Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV (APN+) and the UNAIDS Asia-Pacific Regional Support Team. As part of their shared aim to reduce stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings, these initiatives seek to improve the health experiences of trans people by forging partnerships among providers, policymakers and communities.

“Changes can be made at the facility and community levels that make a huge difference in the lives of transgender people,” said Quinten Lataire, UNAIDS’ Regional Human Rights and Law Adviser. “Collaborating with communities, peer navigation and building friendly clinic services are proven approaches. At the same time transgender clients need training about how to navigate care, along with counselling so they can process the issues around their gender identity.”

Online spaces can play a key role in this community support function. For example, using the UNAIDS COVID-19 Communications Grant, APTN developed a COVID-19 Trans Resilience Social Media Tool Kit that included content on mental health, financial security, social protection and human rights.

Ms Fauziah’s experience bears out the game-changing role communities can play. In 2021 she connected with the organization Sanggar Swara. They have not only supported her treatment adherence but provided emotional support.

“It’s not your job to judge people. When your patient is someone with a different gender or sexual orientation, they only need your help. We need care and we also need space to be ourselves and not have to hide,” Ms Fauziah said.

View APTN’s video “The cost of stigma: transgender individuals living with HIV struggling to access healthcare” (129) The Cost of Stigma: Transgender Individuals Living with HIV Struggling to Access Healthcare - YouTube

Video

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

Asia Pacific women living with HIV speak out about rights violations

08 March 2023

08 March 2023 08 March 2023Nirmala Singh (not her real name) found out she was HIV positive after being tested during pregnancy. It was a surprise diagnosis, but she immediately knew how she had been infected. Before getting married she was raped. Nurses informed Nirmala’s husband of her positive result without her consent. She was immediately kicked out the home.

Sita Shahi, Regional Coordinator of the International Community of Women Living with HIV in Asia and the Pacific (ICWAP), has responded to this and many similar cases in her native Nepal.

“There is very little understanding of the rights of women living with HIV and how their experience is impacted by abuse,” Ms Shahi said. “Women are blamed for transmitting HIV because they are usually first in the family to be diagnosed. That is the starting point for them to experience human rights violations like intimate partner violence in the home and gender-based violence in the wider society.”

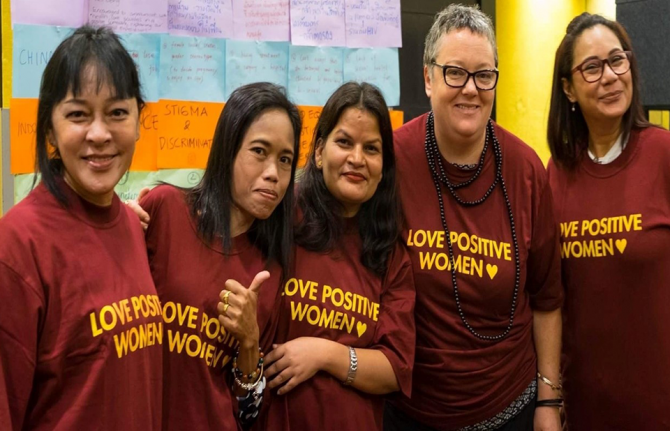

At a UNAIDS-supported ICWAP workshop organized in 2022 with participants from countries across the region, women living with HIV shared their personal stories.

One participant who was diagnosed during pregnancy was refused care by staff during childbirth. She delivered her baby on the floor of her ward, alone.

Some who have survived domestic violence said they were rejected by shelters run by government and non-governmental organisations based on their HIV status.

And there was consensus that in all countries domestic violence is common, but rarely reported.

The concerns of women living with HIV in the Asia Pacific region have remained relatively hidden and ignored. Rates of new infections and AIDS-related deaths among men in the region are more than double those of women. But for the estimated 2.2 million women living with HIV in Asia and the Pacific, smaller numbers do not mean smaller problems.

“Women in Asia and the Pacific continue to face discriminatory policies, social and cultural barriers, inequalities in healthcare access and threats to their security that violate their rights,” said UNAIDS’ Regional Adviser for Community-Led Responses, Michela Polesana.

“When women are free of any kind of stigma and discrimination, gender-based violence or breach of confidentiality by healthcare providers there is no accusing epidemic,” Ms Shahi reflected. “If a woman is free of violence at the policy level, society level and family level she can be mentally strong and her health could be as well as other people’s. Then there is no problem taking care of herself and her family while contributing to the economy.”

As a regional network, ICWAP is working to increase the capacity of organisations for and by women living with HIV so they can advocate around these issues at national level. A key priority is giving stakeholders including healthcare providers the information they need to help uphold the rights of women living with HIV.

One critical element of this strategy has been equipping its membership to advocate effectively using digital tools and spaces. UNAIDS supported social media advocacy training for ICWAP’s Young Advocates Social Media Team. Through the eight-week process, participants were introduced to social media basics, explored sexual and reproductive health and rights issues and practiced skills such as interviewing, blogging and editing.

“We embrace the role of technology in not only providing a space for community-building and psychosocial support for women living with HIV, but also the means to speak out about issues that affect them,” Ms. Polesana said.

To empower women living with HIV to meaningfully engage in decision-making spaces, ICWAP also held a feminist movement building training for women-led networks from six countries. This exercise built the capacity of women living with HIV to engage in programmes that promote gender equality and human rights and to lead advocacy efforts for high quality life-saving services for women and girls across the region.

On International Women’s Day 2023 under the theme “DigitALL: Innovation and technology for gender equality”, ICWAP called for the following:

- User-friendly digital platforms

- Access to the internet and digital tools

- Capacity building around social media advocacy

- Strengthened data security and redress mechanisms

- Online reporting mechanisms and rapid response for intimate partner violence

- Strategies to increase the economic empowerment of women living with HIV

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

How harsh drug laws undermine health and human rights in Asia Pacific

01 March 2023

01 March 2023 01 March 2023Rosma Karlina and Bambang Yulistyo Dwi live with their two young children in the rainy hillside town of Bogor, south of Jakarta.

“Sometimes we go to museums to introduce the children to history or feed the deer at the Presidential Palace. It’s simple entertainment but can teach the children to learn to love even animals,” Ms. Karlina said.

If their family life is traditional, their work life is anything but. Ms Karlina is the founder and Director of Suar Perempuan Lingkar Napza Nusantara (also called Womxn's Voice), an advocacy and care organisation serving women and transwomen who use drugs. Bambang, popularly known as Tedjo, founded the Indonesian Justice Action Foundation (AKSI). Since 2018 his team has provided legal aid and support to people who use drugs, and advocated for their rights.

Their workdays are a mix of community organizing, paralegal paperwork and responding to distress calls. A client reported her husband’s domestic violence. When the police arrived at the house, the husband informed the police of her drug use and the police arrested her instead.

The organisations successfully advocated for a man to be released from a compulsory rehabilitation centre so that he could access HIV treatment. Otherwise, he would have gone three months without his medicines.

The organisations have witnessed many examples of women living with HIV being faced with extreme scorn. A police officer once threw a pack of sanitary napkins into a woman’s cell instead of passing it to her, saying it was because he was afraid to be near her.

“Since 2018 I have seen many rights violations perpetrated by law enforcement officers—abuse physically, psychologically and even financially,” Ms Karlina said. “They extort families to pay to enable their loved ones to go home.”

The Rosma Karlina of today—nurturer and fierce advocate—evolved from almost two decades of drug abuse. She has been to rehabilitation centres 17 times. Rock bottom came during an 18-month incarceration for heroin possession.

“My family paid a lot of money to the prosecutors, but I was still imprisoned. I lost custody of my oldest child. The judge thought I did not deserve to be a mother because I was a drug user,” she recounted.

Tedjo also evolved from addiction to activism.

“I did drugs between 1989 and 2015. It has been a long journey,” he reflected. “When my life was a mess, I hurt many people. It was not easy to prove that I was better.”

The couple are leading voices on how harsh criminal laws for drug possession and use lead to rights violations against people who use drugs while also lowering access to health services.

A 38-country legal and policy analysis by UNAIDS and UNDP found that 14 countries in the region have corporal or capital punishment penalties for the use or possession of drugs. Some states have condoned extrajudicial killings for drug offences. In 2021 an estimated 12% of new HIV infections in Asia and the Pacific were among people who inject drugs.

“The war on drugs has created a lot of stigma, and a culture that views an entire community as criminals. When we access healthcare, we get treated as bad people,” Tedjo said.

Regional Coordinator of the Network of Asian People who Use Drugs (NAPUD), Francis Joseph, explained that in the absence of legally conducive environments people don’t have access to appropriate services.

“Healthcare providers and law enforcement agencies treat them with violence and abuse,” he said. “So they don’t want to come out the closet and say ‘I have shared needles and syringes and I need an HIV test’. Because drug users are not welcome in our health facilities that leads to them going into the shadows and staying there.”

Lord Lawrence Latonio, a Community Access to Redress and Empowerment (CARE) partner and law student noted that Philippines also criminalises the possession of what are seen as drug paraphernalia. This means that peer educators who disseminate clean needles and syringes have to be watchful so they are not apprehended.

Fortunately advocates successfully lobbied for the country’s HIV and AIDS Policy Act of 2018 to include protections for healthcare workers who provide HIV services. Part of CARE’s work is legal literacy training so communities understand their rights. CARE also has a network of peer officers working in different regions to support members of key population communities and people living with HIV with seeking redress in cases where there have been rights violations.

Twenty-one countries in the region operate either state-run compulsory detention and rehabilitation facilities for people who use drugs or similar facilities. These are a form of confinement where those accused of, or known to be using drugs, are involuntarily admitted for detoxification and “treatment”, often without due process. Conditions have been reported to involve forced labour, lack of adequate nutrition, and limited access to healthcare.

In 2012 and 2020 United Nations agencies called for the permanent closure of these compulsory facilities. But according to a 2022 report, progress on this issue in East and Southeast Asia has largely stalled.

“UNAIDS is working with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to support countries to transition from compulsory facilities towards voluntary community-based treatment that provides evidence-informed and human-rights based services,” said UNAIDS Asia Pacific Human Rights and Law Adviser, Quinten Lataire.

UNAIDS Indonesia is working with Womx'n Voice to pilot a multi sector partnership shelter and education program for women and children in Bogor. Interventions include social protection, legal support, mental health support, HIV and health education and accompaniment to services.

Ms Karlina called for increased investments in mental health care, poverty alleviation and education. “We need proper assessments to better look at each situation and come up with an effective solution. Prison is not the answer. If you see us as humans, you will take care of us as humans,” she insisted.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Feature Story

“Silence is better” — How the criminalisation of sex workers keeps exploitation in the shadows

28 February 2023

28 February 2023 28 February 2023As a girl Ikka dreamed of becoming an accountant. She knew her parents could not afford to send her to university, so she resolved to pay for university herself by moving into a brothel. For almost three years she lived and worked there while studying.

Davi’s parents divorced when he was a baby and he was raised by caring grandparents. In high school he led lots of extracurricular activities. He was also gay. Just three months before his final exams Davi was raped by a teacher who threatened to “out” him. He ran away to the city. After a desperate search for work, he landed a job in a massage parlour.

From the Bangkok offices of Youth LEAD and the Asia Pacific Network of People Living With HIV and AIDS (APN+), the pair reflects on those chaotic adolescent years with halting candour. They unpack layers of vulnerability and abuse—the way poverty and trauma can propel young people toward sexual exploitation, higher HIV risk and a cascade of rights violations. And they say that the criminalisation of sex work only made their situations worse.

“No one tells you anything other than that you need to please your client. Just be submissive and quiet. There’s no protection, no information, no nothing,” Ikka remembers.

The brothel would occasionally force the women to undergo HIV and STI testing. Saying ‘no’ wasn’t an option. But when Ikka went to a clinic on her own to get condoms or contraceptives, she was turned away.

Customers sometimes didn’t pay, became violent or refused to stop having sex after even two or three hours. Abusive clients routinely threatened to report them.

“If someone called the police, they would arrest the sex worker. The customer is king,” Davi says. “So silence is better.”

“The police wouldn’t take your report. They think they have more important cases than you,” Ikka adds.

UNAIDS Asia Pacific Human Rights and Law Adviser, Quinten Lataire, explained that criminal laws against sex workers make it very difficult for sex workers to demand basic rights, substantially increasing their risk for abuse and exploitation, such as from law enforcement officers.

“The criminalization of sex workers does not end sex work. It simply makes people go underground, putting them at higher risk of violence and HIV transmission. This has a devastating impact on the sex workers themselves, their clients and the society at large,” Mr Lataire said.

Almost all (99%) new HIV cases in young people in Asia Pacific are amongst key populations and their sexual partners. In Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Thailand, youth account for between 40% and 50% of new infections. Since 2010, HIV rates among young people have risen in Afghanistan, Fiji, Malaysia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Timor-Leste.

At ages 18 and 19 respectively, both Ikka and Davi learned that they were HIV positive. In Ikka’s case she was tested as a VISA requirement for a student exchange programme. Her results were forwarded to her school even before she got them and she was kicked out. From breach of confidentiality to discrimination in both education and healthcare settings—one rights violation after another. Ikka had the agency to confirm her HIV status at a community-based sex worker clinic she’d looked up and immediately started treatment.

Davi voluntarily tested with a community organization that visited the massage parlour to conduct sensitization sessions and offer services. He kept his status a secret at work but began attending support meetings on the weekend. He sometimes told the pimp that he was going out to meet a client, handing over the stipend he got from the organization when he got back.

“For eight months after I knew I was positive, I felt like I didn’t want to do sex work, but I needed the money. I told clients to use condoms but some of them would give me more money not to,” Ikka remembers.

The events that finally prompted her to leave the brothel still evoke strong emotions. Her best friend there also contracted HIV.

“I told her, ‘let’s go together to get antiretroviral treatment’. I showed her my medication as evidence. But she didn’t want to go. She would not get support from her parents and if the pimp found out, he would kick her out. She felt it was better to die,” Ikka remembers. Her friend passed away just two months after her diagnosis.

In both cases these young people demonstrated incredible resilience and were supported by community-led organizations with tailored services for sex workers and people living with HIV. Ikka joined an organization addressing sex workers’ rights, health and social support needs. She quickly carved a niche representing the interests and perspectives of young sex workers. She would go on to lead national young key population organizations and sit on the Global Fund’s Youth Council. Today she is the Regional Coordinator of Youth LEAD.

“I told myself I needed to help my community,” Davi says. “I don’t want no more people in my situation; no more students becoming victims of sexual violence; no more 19-year-olds HIV positive. I just chose to leave (the parlour) and volunteer with the community organization instead.” Encouraged and supported by community, Davi would go on to graduate from high school and earn a sociology degree. He is now aiming for a Masters qualification while working as APN+’s Youth Officer.

The issues Ikka and Davi faced remain today.

“I still use a condom, but many clients refuse,” says Rara, a 22-year-old sex worker. “When we’re desperate for money, we have no choice but to agree. In addition to gonorrhea, I got syphilis and got treated for it. Thankfully I’m still HIV negative.”

UNAIDS and the Inter-agency Task Team on Young Key Populations are working to address the inequalities faced by young key populations in Asia Pacific. Learn more about their work.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025