Injecting drug use IDU

Feature Story

How harsh drug laws undermine health and human rights in Asia Pacific

01 March 2023

01 March 2023 01 March 2023Rosma Karlina and Bambang Yulistyo Dwi live with their two young children in the rainy hillside town of Bogor, south of Jakarta.

“Sometimes we go to museums to introduce the children to history or feed the deer at the Presidential Palace. It’s simple entertainment but can teach the children to learn to love even animals,” Ms. Karlina said.

If their family life is traditional, their work life is anything but. Ms Karlina is the founder and Director of Suar Perempuan Lingkar Napza Nusantara (also called Womxn's Voice), an advocacy and care organisation serving women and transwomen who use drugs. Bambang, popularly known as Tedjo, founded the Indonesian Justice Action Foundation (AKSI). Since 2018 his team has provided legal aid and support to people who use drugs, and advocated for their rights.

Their workdays are a mix of community organizing, paralegal paperwork and responding to distress calls. A client reported her husband’s domestic violence. When the police arrived at the house, the husband informed the police of her drug use and the police arrested her instead.

The organisations successfully advocated for a man to be released from a compulsory rehabilitation centre so that he could access HIV treatment. Otherwise, he would have gone three months without his medicines.

The organisations have witnessed many examples of women living with HIV being faced with extreme scorn. A police officer once threw a pack of sanitary napkins into a woman’s cell instead of passing it to her, saying it was because he was afraid to be near her.

“Since 2018 I have seen many rights violations perpetrated by law enforcement officers—abuse physically, psychologically and even financially,” Ms Karlina said. “They extort families to pay to enable their loved ones to go home.”

The Rosma Karlina of today—nurturer and fierce advocate—evolved from almost two decades of drug abuse. She has been to rehabilitation centres 17 times. Rock bottom came during an 18-month incarceration for heroin possession.

“My family paid a lot of money to the prosecutors, but I was still imprisoned. I lost custody of my oldest child. The judge thought I did not deserve to be a mother because I was a drug user,” she recounted.

Tedjo also evolved from addiction to activism.

“I did drugs between 1989 and 2015. It has been a long journey,” he reflected. “When my life was a mess, I hurt many people. It was not easy to prove that I was better.”

The couple are leading voices on how harsh criminal laws for drug possession and use lead to rights violations against people who use drugs while also lowering access to health services.

A 38-country legal and policy analysis by UNAIDS and UNDP found that 14 countries in the region have corporal or capital punishment penalties for the use or possession of drugs. Some states have condoned extrajudicial killings for drug offences. In 2021 an estimated 12% of new HIV infections in Asia and the Pacific were among people who inject drugs.

“The war on drugs has created a lot of stigma, and a culture that views an entire community as criminals. When we access healthcare, we get treated as bad people,” Tedjo said.

Regional Coordinator of the Network of Asian People who Use Drugs (NAPUD), Francis Joseph, explained that in the absence of legally conducive environments people don’t have access to appropriate services.

“Healthcare providers and law enforcement agencies treat them with violence and abuse,” he said. “So they don’t want to come out the closet and say ‘I have shared needles and syringes and I need an HIV test’. Because drug users are not welcome in our health facilities that leads to them going into the shadows and staying there.”

Lord Lawrence Latonio, a Community Access to Redress and Empowerment (CARE) partner and law student noted that Philippines also criminalises the possession of what are seen as drug paraphernalia. This means that peer educators who disseminate clean needles and syringes have to be watchful so they are not apprehended.

Fortunately advocates successfully lobbied for the country’s HIV and AIDS Policy Act of 2018 to include protections for healthcare workers who provide HIV services. Part of CARE’s work is legal literacy training so communities understand their rights. CARE also has a network of peer officers working in different regions to support members of key population communities and people living with HIV with seeking redress in cases where there have been rights violations.

Twenty-one countries in the region operate either state-run compulsory detention and rehabilitation facilities for people who use drugs or similar facilities. These are a form of confinement where those accused of, or known to be using drugs, are involuntarily admitted for detoxification and “treatment”, often without due process. Conditions have been reported to involve forced labour, lack of adequate nutrition, and limited access to healthcare.

In 2012 and 2020 United Nations agencies called for the permanent closure of these compulsory facilities. But according to a 2022 report, progress on this issue in East and Southeast Asia has largely stalled.

“UNAIDS is working with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to support countries to transition from compulsory facilities towards voluntary community-based treatment that provides evidence-informed and human-rights based services,” said UNAIDS Asia Pacific Human Rights and Law Adviser, Quinten Lataire.

UNAIDS Indonesia is working with Womx'n Voice to pilot a multi sector partnership shelter and education program for women and children in Bogor. Interventions include social protection, legal support, mental health support, HIV and health education and accompaniment to services.

Ms Karlina called for increased investments in mental health care, poverty alleviation and education. “We need proper assessments to better look at each situation and come up with an effective solution. Prison is not the answer. If you see us as humans, you will take care of us as humans,” she insisted.

Region/country

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Documents

Dangerous inequalities: World AIDS Day report 2022

29 November 2022

This report, which marks World AIDS Day 2022, unpacks the impact that gender inequalities, inequalities faced by key populations, and inequalities between children and adults have had on the AIDS response. It is not inevitable, however, that these inequalities will slow progress towards ending AIDS. We know what works—with courage and cooperation, political leaders can tackle them. Read press release. Report introduction available in languages, including Arabic, French, Russian, Spanish.

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Feature Story

Sustaining HIV services for people who use drugs in Odesa

22 April 2022

22 April 2022 22 April 2022Odesa is a major Black Sea port, with a substantial drug use. In the 1990s, Odesa saw the outbreak of HIV infection in Ukraine. But more recently it has successfully developed one of the world’s most effective systems of harm reduction services for people who use drugs. The system is funded by the state and local budgets and implemented jointly with non-governmental and community organizations. Odesa was one of the first cities in Eastern Europe and Central Asia that signed the Paris Declaration. Last year, it reported a reduction of new HIV cases among people who use drugs.

Natalia Kitsenko is head of the public health department of the Road to Home Foundation, one of Odesa’s oldest organizations providing services to people who use drugs. UNAIDS spoke with her about how her organization has been managing to continue to help people in need, even during this war.

Question: Did many people flee Odesa?

Answer: Yes, many left, mostly women and children. The people in our organisation are an exception. Of 60 employees, 4 people left because they have small children. The rest stayed and we are actively continuing our usual work and also providing emergency assistance to women with children and elderly people fleeing from other cities—Mykolaiv, Kherson, Mariupol and Kharkiv. We mostly provide transportation to the Moldova border and connect them with volunteers who then help them in the country or in another destination depending on their needs.

We also prepare food such as pies and dumplings for people in need. This whole situation has united us; I have seen a lot of mutual support around.

Question: How many people from your harm reduction program have left the city?

Answer: Our coverage in Odesa and surrounding region includes about 20,000 people per year. As far as we know only 7 clients have fled abroad. Some clients have gone into the local territorial defense groups. Others have taken part in building protective structures, which involves collecting bags of sand and transporting them to protect streets and monuments. Others reside with us for the services they need. We had an influx of people who use drugs from other regions of Ukraine where conditions are far worse.

Question: What services does your organization offer to people who use drugs?

Answer: First of all the basic harm reduction package which we provide under the state budget includes consultations, HIV prevention (syringes, condoms, wipes, lubricants, etc.); HIV testing, and TB screening. Among clients who have used these services for a long time, the detection rate of HIV infection is 0.02%. Among new clients who have just joined the programme, it reaches up to 7%. We set up a client recruitment model with the Alliance for Public Health coordination using the Global Fund Grant and ECDC support. We encourage people who use drugs to bring their close friends to our community centres for testing. This is an important aspect because new clients, especially young people, those who recently started using drugs, can be a very difficult group to reach. Many hide their use and try to stay invisible. This recruitment system allows us to attract them to our harm reduction services, and first of all to testing. Management of new cases, support for diagnosis and receiving antiretroviral therapy, screening, and follow-up for tuberculosis is also provided through donor funding, in particular the PEPFAR project.

Question: Have you gotten additional funds?

Answer: Yes. We just received additional funding from the UNAIDS Emergency Fund to purchase medicines, dressings and hygiene products for our clients. This is a very timely and essential help because many medical products like Fluconazole (antibiotic) are not affordable to our clients and they are not widely available anymore.

Question: Natalia, you have been working in the HIV field for more than 20 years, have public attitudes changed regarding people living with HIV and drug users?

Answer: We have seen a welcome dramatic reduction in the level of stigma and discrimination and the overall attitude towards our clients in medical settings. However, we still experience problems with prejudices. Many people say that they do not want to have our syringe exchange points and community centers near their homes, and that they don't want to see people who use drugs near them as they fear that they might threaten their comfort, well-being and safety. We understand these fears, and we try to explain to concerned people why we are here, how these syringe exchange points and community centers work. We organise outings and sessions to explain to people the reality that people who use drugs face. We work to continually demonstrate our contribution and show how we help keep the epidemics of HIV, TB and hepatitis under control.

Since the war started we have also provided shelter to people who live by our centres. As our syringe exchange points are usually in basements, when the sirens sound the neighbors come to us; and that means for some their first time being in close contact with people living with HIV or people who use drugs.

Question: What are the most pressing issues for you now?

Answer: At the moment we are experiencing difficulties in providing our customers with Naloxone, which can prevent drug overdoses. Although we are constantly working on counseling and informing people about signs of overdosing, with the war going on, overdoses have increased. And because Naloxone is manufactured in the heavily bombed city of Kharkiv we have no more. We need it in any form, preferably ready-made, intranasal or injectable, as this would save many lives. And we need to sustain HIV services for people who use drugs together with providing them with urgent humanitarian aid.

Region/country

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Feature Story

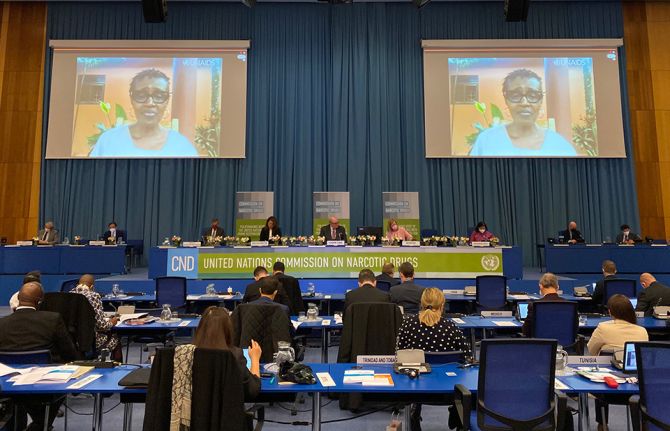

UNAIDS Executive Director's Statement at the 65th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs

14 March 2022

14 March 2022 14 March 2022Introduction

Thank you Ambassador Ghislain D'hoop and Belgium as the Chair of the 65th Commission on Narcotic Drugs, distinguished members of the Commission, Member States, Civil Society and networks of people who use drugs, UN agencies and all colleagues.

I thank very much my sister Ghada Waly for your strong leadership of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and your unequivocal support for the United Nations common position on drug policy.

I’d like to begin by expressing my solidarity for the people of Ukraine, who have suffered so much violence and injustice. For the last 15 years, Ukraine has had one of the largest and most successful HIV responses in Europe.

Now the entire HIV response is collapsing, and the lives of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians living with HIV and the key groups are hanging by a thread.

I call on all partners to work to restore essential services for people living with and affected by HIV in Ukraine.

Last June, Member States adopted the 2021 Political Declaration on Ending AIDS. The resolution contains bold commitments, including new targets for 2025 to bring the response back on track to end AIDS by 2030.

Last year UNAIDS worked with all countries and partners to develop and adopt the Global AIDS Strategy. The golden thread of the strategy is on ending inequalities in an epidemic where 65% of all new infections are within particular groups – and these include people who use drugs and prison inmates.

We know that if we continue as we are, if we do not close the inequalities in the HIV response - the world could see 7.7 million AIDS deaths over the next ten years.

The global HIV response, which was already off track before COVID-19, is now under even greater strain as the COVID-19 crisis continues.

And people who use drugs and prisoners continue being among the most affected!

Globally, harm reduction services are not available at the level and scale that is required to end AIDS. And that’s true in the community and in prisons. In too many countries, they are not available at all.

Without continued access to HIV and harm reduction services, we will not end AIDS among people who use drugs and prison inmates, and we will therefore not end AIDS at ALL.

Key barriers to access to HIV and harm reduction services for people who use drugs and prisoners are criminalisation, stigma and discrimination.

We will not end inequalities and end AIDS without addressing these barriers and removing punitive laws and policies.

In particular, women who use drugs face legal, policy and social barriers to accessing life-saving HIV and harm reduction services; we need to invest in non-judgmental harm reduction services tailored to the needs of women.

We have an ongoing funding crisis for harm reduction in low-and middle-income countries. Government and donors have invested just 5% of the funds needed for an effective response. We need to scale up investment now, with a focus on funding for community-led responses. They are the most effective.

CONCLUSION

Members of the Commission, I believe in your leadership.

We must value the health and human rights of every person who uses drugs and the dignity of every prisoner.

We must implement our commitments to create enabling legal environments. We must promote and scale-up harm reduction as a safe and effective approach essential to end AIDS.

We must remove punitive and discriminatory laws and policies. This includes laws that criminalize drug use and possession as set out in our new Global AIDS Strategy.

Our work to end the inequalities that drive AIDS must be based on science, evidence and human rights.

I urge you Commissioners to uphold these principles to get us back on track to end AIDS by 2030.

I thank you all for your attention.

Winnie Byanyima

UNAIDS Executive Director

Vienna, 14 March 2022

"Without continued access to HIV & harm reduction services, we will not end AIDS among people who use drugs & prison inmates, and we will therefore not end AIDS at ALL."

— UNAIDS (@UNAIDS) March 14, 2022

Watch @Winnie_Byanyima's opening remarks at #CND65 @UNODC @CND_tweetshttps://t.co/c7McJbOv1A pic.twitter.com/LZWDdf6gWJ

65th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Our work

Related

55th meeting of the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board

10 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

20th Indian Ocean Colloquium on HIV/AIDS

22 October 2024

Club Eney: a safe place for those left behind

Club Eney: a safe place for those left behind

21 October 2024

University of Pompeu Fabra

17 October 2024

Linking UN Summit of the Future with COP29

26 September 2024

Revitalized Multilateralism

24 September 2024

Plenary debate of the Summit of the Future

23 September 2024

African Union Year of Education

23 September 2024

Feature Story

New indicators added to Key Populations Atlas

06 January 2022

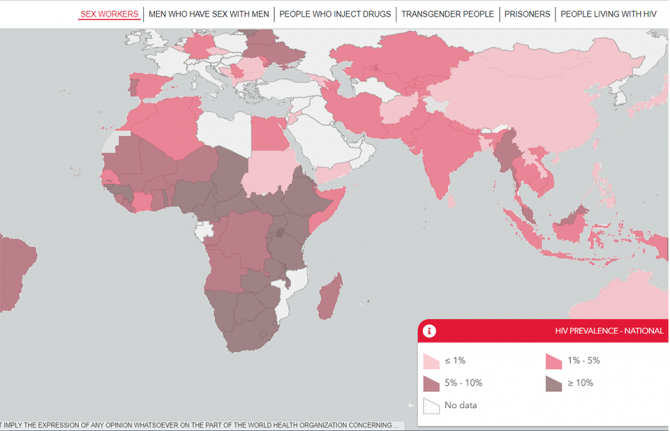

06 January 2022 06 January 2022The UNAIDS Key Populations Atlas is an online tool that provides a range of information about members of key populations—sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, transgender people and prisoners—worldwide, together with information about people living with HIV.

Information about gay men and other men who have sex with men has been expanded with the inclusion of 11 new indicators from the EMIS and LAMIS projects. Under funding from the European Commission, EMIS-2017 collected data from gay men and other men who have sex with men in 50 countries between October 2017 and January 2018. LAMIS is the Latin American version of EMIS and finished data collection across 18 additional countries in May 2018.

The 11 new indicators shown in the Key Population Atlas—on syphilis, symptomatic syphilis, gonorrhoea, symptomatic gonorrhoea, chlamydia, symptomatic chlamydia, sexually transmitted infections testing, syphilis partner notification, gonorrhoea partner notification and hepatitis A and B vaccination—were chosen because of their high relevance to the communities.

Community-led and community-based infrastructure is essential for addressing the inequalities that drive pandemics such as the AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics, as well as for ensuring the continuity of health services and protecting the rights and livelihoods of the most vulnerable. The EMIS and LAMIS findings will be important for informing civil society organizations working on sexual health, HIV prevention and sexual minority rights and for policymakers, non-community prevention planners, epidemiologists and modellers.

“To leave no one behind, we need people-centred data collection that spotlights the inequalities that are hampering access to services. It is critical to understand who are the most affected and unable to access services. This will enable the European Commission, European Union Member States and civil society and community organization alike to address the specific needs of gay men and other men who have sex with men,” said Jantine Jacobi, the UNAIDS representative to the European Union.

Civil society and community-based organizations, especially those led by key populations, can complement traditional health systems’ pandemic responses, but this requires that they be treated as full partners—involved in governing, designing, planning and budgeting pandemic responses––with the technical and financial support to do so effectively.

The findings of the new indicators will help to increase the role of partnerships and communities across each country and will serve as the basis for decision-making and policy planning. For example, in Ireland, the EMIS-2017 National Report acknowledges that, “there has been an increase in HIV and STI testing compared to previous surveys and this is in some part due to the positive interventions carried out by stakeholders and the MSM [men who have sex with men] community in response to findings from previous surveys. Some of these positive interventions in relation to HIV testing can also be attributed to the increased availability of community testing.”

Our work

Feature Story

Empowering people who inject drugs in Uganda

18 January 2022

18 January 2022 18 January 2022The hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have magnified the challenges that people who use drugs face.

In Uganda, during the COVID-19 lockdowns there was limited access to HIV treatment and other health services, including access to medically assisted therapy, which provides daily doses of methadone to people who use drugs. Access to support systems, such as drop-in centres, was also affected.

“During the COVID-19 lockdown, access to medically assisted therapy for a daily dose was really hard for me, since movement was restricted and we required permission from the area local council. However, getting permission for a travel permit from the local council was very hard and took time, so it became challenging to sustain without access to these crucial services,” said Nsereko Joshua (not his real name), who is currently undergoing medically assisted therapy.

An analysis conducted by the Uganda Harm Reduction Network (UHRN) in July 2020 on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic showed a decline in access to condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis, counselling, psychosocial support, HIV testing, sexual and reproductive health services and legal aid services. It also highlighted a 25% increase in human rights violations reported among people who inject drugs during the COVID-19 lockdown. Issues included an increase in arrests and detentions, gender-based violence and eviction from their houses by the police at night.

When the UNAIDS Solidarity Fund for key populations was announced in December 2020, Wamala Twaibu, the founder and Chairperson of the Eastern Africa Harm Reduction Network and UHRN, saw an opportunity to empower people who inject drugs. He envisioned a transformed community that could support one another when in need, managing their own income sources.

“I was an injecting drug user for more than seven years, and I know what a drug user goes through daily. My aspiration is to improve the health, human rights and socioeconomic well-being of people who use drugs,” he said.

Mr Twaibu noted that injecting drug use and drug dependence often have long-term impacts on a person’s socioeconomic status and health outcomes. The lack of work skills, past criminal histories, stigma and discrimination and the criminalization of drug use are some of the main issues that people who inject drugs face regularly.

UHRN applied for the UNAIDS Solidarity Fund grant to kickstart the Empowered PWID Initiative for Transformation (EPIT) project, which was awarded in 2021. Through the EPIT project, community members currently on medically assisted therapy will be equipped with skills in craft-making for a sustained livelihood. Mr Twaibu noted that knowledge and skills in small-scale business management for people who inject drugs will form the core of the project.

About 80 people who inject drugs on medically assisted therapy will be engaged in the EPIT project, clustered in 16 cohorts with five members in each cohort and with at least six women-led cohorts across the five divisions of Kampala.

To ensure the sustainability of the initiative, a “Save, take and return” approach will be used. This strategy encourages beneficiaries to save some of the profits of the social enterprises every day, which they can get back after a few months.

“This fund looks at the socioeconomic empowerment of key populations, led by the affected community. That is the catch. Community ownership of the initiative is important because nothing for us without us,” said Mr Twaibu. “Change is possible when we support each other without discrimination and stigma. I wish to see a transformed and empowered people who inject drugs community that can support one another when in need,” he added.

Thinking about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic so far, Mr Twaibu worries that the next wave of COVID-19 might affect the programme. However, he envisions a fully established and functional craft-making programme in the five divisions of Kampala and a scale-up in other regions where UHRN works.

Now that he is a part of the EPIT project, Mr Joshua expresses hope for a brighter future. “I yearn to have a complete recovery from drug addiction, and I believe that medically assisted therapy will do this for me,” he said. “And I believe the EPIT programme will give me an opportunity to develop and demonstrate my readiness for my recovery with the ability to earn something for my survival and for transport to seek my treatment. I think even after this programme, the skills will help me to sustain my family and myself as well.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

Zambia - an HIV response at a crossroads

24 February 2025

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

Status of HIV Programmes in Botswana

20 February 2025

Documents

HIV and people who use drugs — Human rights fact sheet series 2021

02 June 2021

The 2021-2026 Global AIDS Strategy has bold and critical new targets on realizing human rights, reducing stigma, discrimination and violence and removing harmful punitive laws as a pathway to ending inequalities and ultimately ending AIDS. To aid in the scale up of interventions to remove these societal barriers, UNAIDS has produced a series of fact sheets on human rights in various areas, highlighting the critical need to scale up action on rights. They are a series of short, easy to digest and accessible documents outlining the latest epidemiology, the evidence of the impact of human rights interventions, the latest targets, and international guidelines, recommendations and human rights obligations relating to each topic. Fact sheets: HIV criminalization, HIV and people who use drugs, HIV and gay men and who have sex with other men, HIV and transgender and other gender-diverse people, HIV and sex work, HIV and people in prisons and other closed settings and HIV and stigma and discrimination. This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Take the rights path to end AIDS — World AIDS Day report 2024

26 November 2024

Club Eney: a safe place for those left behind

Club Eney: a safe place for those left behind

21 October 2024

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

Peru approves groundbreaking law to extend health coverage for migrants with HIV and TB

21 October 2024

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

UNAIDS statement on anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Georgia

01 October 2024

Update

Harm reduction services reduce new HIV infections

01 November 2021

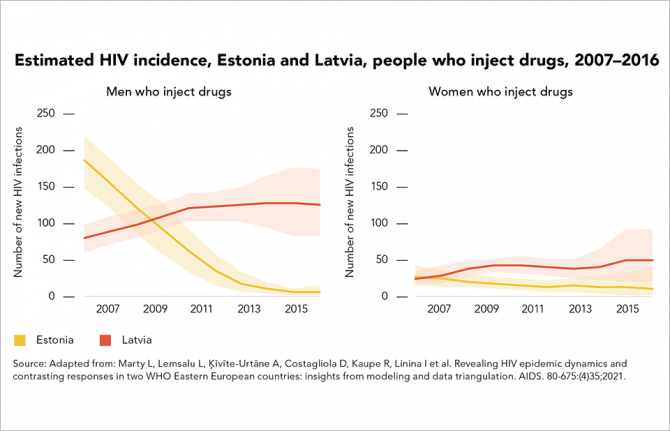

01 November 2021 01 November 2021The neighbouring Baltic states of Estonia and Latvia offer starkly contrasting examples of how different public health approaches affect HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs. In the early 2000s, the two countries had among the highest rates of HIV diagnosis in Europe. As was the case for many European countries at that time, the sharing of non-sterile injecting equipment among drug users was fuelling their HIV epidemics.

The two epidemics began to diverge in the mid-2000s. According to the HERMETIC study, new HIV infections in Estonia declined by 61% countrywide and by 97% among men who inject drugs between 2007 and 2016.

Latvia’s HIV epidemic followed a different trajectory. The HERMETIC study highlights that, between 2007 and 2016, new HIV infections increased by 72% overall. By 2016, overall HIV incidence in Latvia was almost double that in Estonia (35 cases per 100 000 people versus 19 cases per 100 000).

Both epidemics centred largely on the sharing of injecting equipment by people who inject drugs, and probably on unprotected sex between people who inject drugs and their sexual partners. The HERMETIC study concludes that the main difference between the two epidemics lay in the availability of harm reduction services.

Needle–syringe programmes had been operating in Latvia since 1997, but on a very limited scale. As late as 2016, Latvia was distributing about 93 needle–syringes per drug user per year; neighbouring Estonia was distributing 230 per user per year. Both countries expanded access to opioid substitution therapy, which is proven to reduce drug injecting and HIV transmission, and improved HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy services for people who inject drugs. Although access to opioid substitution therapy remained limited in both countries, it was higher in Estonia than in Latvia.

The HERMETIC study’s results indicate that by 2016, about half the people who inject drugs in Estonia were taking HIV tests in a 12-month period—and three quarters of those who tested HIV-positive were on antiretroviral therapy. In Latvia, meanwhile, about 10% of people who inject drugs took an HIV test in any given year between 2007 and 2016, and only 27% of those living with HIV were on antiretroviral therapy. Slow adoption of international HIV treatment guidelines contributed to the low treatment coverage in Latvia.

Related

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

Government ensures continuity of treatment in Malawi

10 February 2025

Press Statement

On International Drug Users’ Day, UNAIDS calls for action against the criminalization of people who use drugs and for community-led harm reduction programmes

01 November 2021 01 November 2021GENEVA, 1 November 2021—On International Drug Users’ Day, UNAIDS is calling for urgent action against the criminalization of people who use drugs, for the redress of criminalization’s negative effects on HIV, viral hepatitis and other health issues, for the respect of human rights and for more funding for community-led harm reduction programmes.

“UNAIDS is committed to supporting countries in their journey towards the decriminalization of drug possession and to full-scale implementation of harm reduction programmes,” said UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima. “UNAIDS calls for the full involvement of communities of people who use drugs in achieving legal reform aimed at decriminalization and in the organization of harm reduction programmes at the country level. This will help us to end inequalities and end AIDS.”

People who use and inject drugs are among the groups at highest risk of acquiring HIV but remain marginalized and often blocked from accessing health and social services. In 2020, 9% of all new HIV infections were among people who inject drugs. Outside of sub-Saharan Africa this rises to 20%. Although women represent less than 30% of the number of people who use drugs, women who use drugs are more likely to be living with HIV than their male counterparts.

Timely introduction and full-scale implementation of accessible harm reduction programmes can prevent HIV infections, as well as many cases of viral hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis and drug overdose. The United Nations system is united in promoting harm reduction services and decriminalization of personal possession of drugs, based on the evidence that harm reduction and decriminalization provide substantial public and personal health benefits and do not increase the number of people with drug dependency. Despite this position, reflected in the United Nations system common position supporting the implementation of the international drug control policy through effective inter-agency collaboration, in reality less than 1% of people who inject drugs live in countries with the United Nations-recommended levels of coverage of needles, syringes and opioid substitution therapy, and the funding gap for harm reduction in low- and middle-income countries sits at a dismal 95%.

Even where harm reduction services are available, they are not necessarily accessible. Punitive drug control laws, policies and law enforcement practices have been shown to be among the largest obstacles to health care in many countries. Criminalization of drug use and harsh punishments (such as incarceration, high fines or removal of children from their parents) discourage the uptake of HIV services, drive people underground and lead to unsafe injecting practices, and increase the risk of overdose. Women who use drugs face higher rates of conviction and incarceration than men who use drugs, contributing to the increased levels of stigma and discrimination they face in health-care settings. In effect, criminalization of drug use and possession for personal use significantly and negatively impact the realization of the right to health.

Earlier this year, United Nations Member States set bold global targets on decriminalization of drug possession for personal use and on elimination of stigma and discrimination against people who use drugs and other key populations. To reach these targets by 2025, strategic actions at the country level need to start today.

GLOBAL AIDS SOCIETAL ENABLER TARGETS 2025

- Less than 10% of countries criminalize drug use and possession of small amounts of drugs.

- Less than 10% of people who use drugs report experiencing stigma and discrimination.

- Less than 10% of people who use drugs lack mechanisms for people living with HIV and key populations to report abuse and discrimination and seek redress.

- Less than 10% of people who use drugs lack access to legal services.

- Less than 10% of health workers and law enforcement officers report negative attitudes towards people who use drugs.

- Less than 10% of people who use drugs experience physical or sexual violence.

GLOBAL PREVENTION TARGETS 2025

- 90% of people who inject drugs have access to comprehensive harm reduction services integrating or linked to hepatitis C, HIV and mental health services

- 80% of service delivery for HIV prevention programmes for people who use drugs to be delivered by organizations led by people who use drugs

International Drug Users’ Day

1 November is International Drug Users’ Day, when the global community of people who use drugs comes together to celebrate its history and affirm the rights of people who use drugs. The International Network of People who Use Drugs (INPUD) marks this day with a celebration of its diverse, vibrant communities’ accomplishments, while also acknowledging their work is more critical than ever.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.